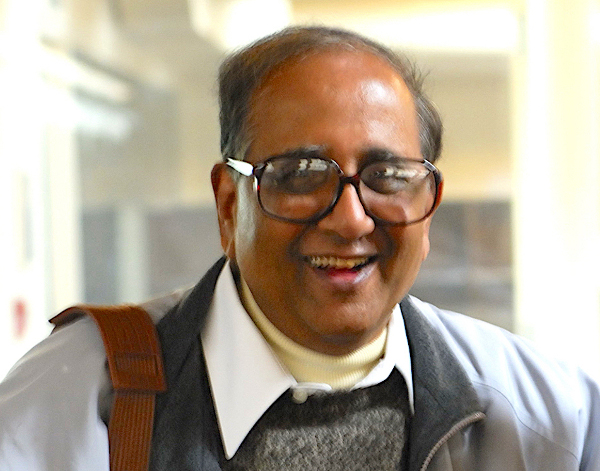

V.S. Varadarajan is Professor Emeritus and Distinguished Research Professor at the Department of Mathematics, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He received his PhD from the Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata in 1960 and has been at UCLA for over five decades. In a gesture of gratitude for his long association, Varadarajan and his wife Veda recently instituted the Ramanujan Visiting Professorship in UCLA’s mathematics department. Varadarajan is the editor of the five volumes of Harish-Chandra’s collected works. In a conversation with C.S. Aravinda, Chief Editor of Bhāvanā, he fondly recalls the evolution of his distinguished career.

It is indeed a pleasure to welcome you on behalf of Bhāvanā to this edition of our “In Conversation” session. Many thanks for accepting to speak to us. When I was researching and forming my thoughts for this conversation, I noticed that you were born in Bangalore.

VSV: Yes, in Bengaluru… near Benne Govindappa choultry in Basavanagudi.

That’s actually the city I come from. And this location is all very familiar to me as I live in south Bengaluru, about two kilometres from Basavanagudi. Perhaps your parents lived there, or your mother’s parents lived there?

VSV: My mother’s side of the family lived there, and in those days, it was common for an expecting mother to go to her maternal house during her pregnancy. So I was born there but have never lived there. My mother’s parents come from Hosur, which is on the boundary between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. My grand-uncle—that is my maternal grandfather’s brother—was C. Rajagopalachari, or Rajaji as he is popularly known.

Oh, Rajaji is a very well-known personality who took part in India’s struggle for independence from British rule. That is a very illustrious background.

VSV: Certainly the most distinguished man in the clan. He had that great feeling for the country, and he fought for independence. What we do is nothing compared to it.

We have heard his voice in the introduction to Bhaja govindam, in that long play gramophone record of M.S. Subbulakshmi; such a clear and wonderful introduction.1 That’s a lovely note to start our conversation! So you wouldn’t remember anything of Bengaluru?

VSV: Almost nothing. My mother’s elder sister and her husband lived in Mysore state but not in Bengaluru. They lived for some time in Shivamogga and I used to go there for summer vacations. He was a singer and I used to sing with him.

I see. Used to sing, meaning Carnatic music?

VSV: Yes. I sang before Rajaji.

That’s great. Did you have a formal training?

VSV: No, nothing formal. At that time, in the All India Radio, there was a programme for self-learning by K.C. Thyagarajan and I followed that everyday.

So music was there at home constantly. Did your parents live in Chennai at the time you were growing up?

VSV: Not in Chennai but in smaller places. My father, Seshadri, was an inspector of schools in the department of education, so we lived in what’s called Mofussil [region outside urban centre]. That is outside the [then] Madras city, and I came to the city when I was in my early teens and where my college education started.

Did your school education also happen in Chennai?

VSV: No. School education happened in Trichinopoly and Salem, because my father kept getting transferred. I was mostly educated in Jesuit schools.

Was it in English medium?

VSV: In Tamil medium, until I joined College in Madras. My father was transferred to Madras and there the medium of instruction was generally English.

When you say college, would it mean after high school?

VSV: Well, in the Indian system, after high school you [used to] study what is called intermediate, for two years. My intermediate was in Loyola College and then I went for a three-year honours degree in statistics in Presidency College.

All these are very illustrious institutions with a long history. So, at some point you moved there from Salem, which is a lovely place, located at the foothills of Yercaud. Did this ambience have any bearing on you, in the sense that you were attracted by the verdant surroundings or were you always sort of a studious person?

VSV: I was always studious. We were from a middle-class family and didn’t have the luxuries to go on outings.

When you say your father was a school inspector, one can imagine that it must have been a modest living. When was it that you got interested in mathematics?

VSV: Very early, when I was 12 years old. In school, I happened to work out problems and so on, but it started seriously when I was in Loyola College.

Was Father Racine there at that time?

VSV: Yes, but he didn’t teach intermediate classes. I was taught maths by K.A. Adivarahan. He was a big figure in Loyola College. I liked to solve problems from books and so on.

Which books? The usual textbooks or was there any particular book that you found interesting?

VSV: I don’t quite remember, but I remember that when I was in honours, I read a book on projective geometry by Russell.2 I was solving geometry problems, as I felt geometry was the easiest subject to have been introduced to. One studied projective geometry from the 10th standard, but it had nothing to do with modern mathematics.

Any special recollections you have of your teachers there, particularly Adivarahan?

VSV: I think Adivarahan was the one who made the strongest impression. I remember the other teachers but they didn’t make such a strong impression. Adivarahan was a legend in Loyola College and a very strict disciplinarian as well. A typical student would be scared to talk to him. Also, you see, the classes for maths, the special subject, were smaller. Whereas English class would have around 300 students from all the sections combined. So a lot more students, which meant a lot less discipline.

Did you also play any sport?

VSV: Well, we played cricket and soccer but we were always on the losing side. Soccer was the simplest because there was no capital needed aside from a ball. I don’t remember winning a single game.

I see. When you say game, would it be inter-class or inter-school competitions?

VSV: No, no. Outside, in the maidan near our house, but you had to be very careful because the end of sunlight comes like a crack in the tropics. And if you were outside the house when the lights are already on, then it meant trouble.

Exactly. Because it’s closer to the equator, the sun almost sets at 90 degrees.

VSV: So you have to be careful in estimation. It is not like there is a long twilight. One moment it is sunny and then it’s suddenly dark.

Right. It’s interesting. The first time I visited upstate New York, I recall observing that the sun would set but at such an angle that, even after setting, it was still not too far below the horizon, and we still had some light. Talking about this, were you also interested in astronomy, star-gazing and such?

VSV: No. I was immersed in cricket! I was the storehouse of information in cricket. I used to listen to commentary on the radio—I even have listened to Bradman playing.

I see. Which year would that be, roughly?

VSV: 1948. It’s great to recall all that. In those days there was no television; so you couldn’t watch, but if you were a close listener, you could imagine the entire field placements. Commentary produces everything. You can actually visualise, and imagine the strokes played, where and to whom the ball went, and so on. You sat glued to the transistor or the radio sets.

And listening to the commentary is also a way to pick up some good English vocabulary. Did that happen to you too?

VSV: Yes, certainly. Though we studied in Tamil medium, the English teachers were very good. So the transition from vernacular to English in college was very smooth. We had very good training in classical English, studying the works of Shakespeare, poets like Wordsworth and so on.

My maths teacher in 10th standard, who taught geometry, was O.V. Rajagopalan. He had a habit that, once a week, no word will be uttered in the class. If the proposition is drawn on the board, you had to indicate what the hypothesis was, and you had to argue using your hands, without speaking a word, to reach the conclusion.

No speaking at all. I see.

VSV: No speaking. Only through hand movement. It was quite a challenge, but Rajagopalan was a great teacher.

I was the storehouse of information in cricket

So in a sense the grounding in mathematics, geometry and music were all a part of your life that absorbed you all the time.

VSV: More or less. There was also a definite background of patriotism. I read books like The Discovery of India by Jawaharlal Nehru. That, and cricket.

Cricket, yes. How would you describe yourself, batsman or bowler?

VSV: I was a bowler, an off-spinner. I didn’t have enough strength to bat—we were all under-nourished.

That’s interesting. One of the Indian great off-spinners, Venkataraghavan, came from Chennai. Did you ever get to see him?

VSV: No. By that time I was in America. But I remember following the famous spin quartet—Prasanna, Chandrasekhar, Bedi and Venkataraghavan.

That was really a fantastic time. That’s the time I was growing up and getting interested in cricket.

VSV: I was once vacationing in India, watching a game. Vivian Richards came and hit 3 sixes and 3 boundaries off a certain bowler. This was the December 1974 test match that India played against the Windies in Delhi. I said “Who is this bowler?’’ They said it was Bishen Singh Bedi. India never produced a fast bowler, except Kapil Dev. It has to be part of a strong routine. It is very hard training to be a fast bowler. Temperatures are high. Where will they train?

And I think the pitches in India have also traditionally favoured spinners.

VSV: Pitches were made for the batsmen. People like to see big scores, but that would be demoralizing for the bowler. Bradman also did something similar to some other bowler, and the wicket-keeper told the bowler that he actually had Don in two minds—whether to go for a six or a four! This was his last tour, against England. Bradman was astonishing. That was the last over. I remember it was 1948, and because of time difference the game commenced late in the evening—9 o’clock or 10 o’clock—and I had to keep the radio very very low so that I didn’t wake up the people who were sleeping. At that time, an Australian over used to be eight balls, but nowadays I think it is six.

You had to indicate what the hypothesis was, and argue using hands to reach the conclusion, without speaking a word

Yeah, everywhere, it’s uniformly six now. So in high school, you were saying that Rajagopalan taught geometry.

VSV: Yes, in 10th standard. It was optional mathematics at that time.

Oh, you could choose an option in 10th standard?

VSV: Yes. You had to take that if you wanted to get into the MPC [Maths, Physics, Chemistry] group in the university. For me there was no question of taking anything else.

Was there anything particular that fascinated you in mathematics?

VSV: I was good with numbers. So there was a vague idea that I should become a mathematician. But I had no idea whatsoever as to what being a mathematician entailed.

And surely you had heard the name of Ramanujan by then.

VSV: Yes, by then I had heard of him and had even looked at some parts of his notebook in some magazine. I didn’t understand a thing.

When did you first hear the name of Ramanujan?

VSV: When I was in school, but I had only scattered information. I think to really learn about Ramanujan, I had to read Hardy’s lectures but that was much later when I was already a professional mathematician. So at the time I was in school, Ramanujan was only a distant role model. I had no clear idea of why he was great. I knew that there was some aura attached to him, that he was untutored and so on.

So, your honours in Presidency College would have been for three years, and in mathematics, right?

VSV: Yes, three years, but it was statistics honours. It is the same as mathematics honours so far as the pure math part is concerned, and they [maths honours students] studied applied mathematics but we studied statistics. For us, it was a question of getting a job.

I think Varadhan also mentioned this when we spoke to him.3 I would like to backtrack a little bit. When you said that in cricket you were a storehouse of information, I wanted to say that you were perhaps a statistician in the making…

VSV: Yes, but I joined statistics honours because everybody said it will lead to a job, plus I found out that the mathematics syllabus was the same as in mathematics honours so I was not losing anything.

And statistics being a mathematical discipline too, it kind of gelled quite well with your interest. Did you also study physics or was it only statistics and mathematics?

VSV: No. Only statistics and mathematics.

And then you went to ISI Calcutta [now Kolkata].

VSV: Yes, this was in the fifties. That was a big change.

Could you please recollect your memories of that time?

VSV: Well, it was an institution devoted primarily to statistics but they occasionally selected people in mathematics. So, somehow or the other I found that I was part of a group of three or four people and we studied on our own.

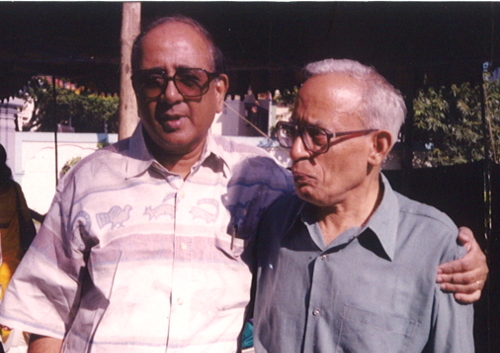

We have heard of the famous four, and I guess that is the group you are referring to?

VSV: Yeah, Parthasarathy, Ranga Rao, myself, and Varadhan. Varadhan came a little bit later. He is four years younger than me. He came to the institute when I was already about to leave for the United States but others were still there. All the four were together only for a very short time but after I came back, Varadhan and I were there and we worked together for some time before he went to New York.

When you said that ISI was “a big change”, what exactly did you mean?

VSV: Well, I meant the learning of real mathematics. There were no teachers in mathematics. We did everything ourselves. So we were self-taught in that sense. We were a very small group of people with very similar interests. There were many young people there but only the three of us—Parthasarathy, Ranga Rao and me—were mathematically inclined, and that was a transformational period.

How did you hear about ISI? What made you choose ISI?

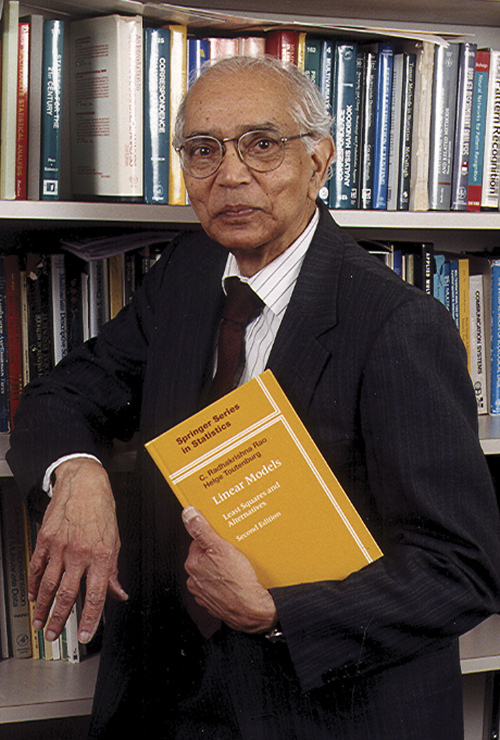

VSV: C.R. Rao had come to Presidency College to give a talk. I was very impressed by it and, after I finished my honours, I wrote to him that I would like to get a job, and he invited me for an interview, after which they selected me.

So it worked out well, and eventually C.R. Rao was your PhD advisor, right?

VSV: Yeah, but also R.R. Bahadur. He was a very, very nice man. Actually there was no supervisor–student relationship. The thesis problem was also suggested by myself. All three of us were like that. We divided what is to be done, and ran a seminar.

C.R. Rao is now 98 and lives in Buffalo. I guess you would be in touch with him?

VSV: Occasionally I enquire about his health. I need to confine myself to emails because I think he cannot hear properly, but he is very prompt in replying to emails as he is taken care of by his daughter.

C.R. Rao’s presence also must have been a very big influence, I would imagine.

VSV: Oh, it was a very inspiring presence. Very inspiring. He worked all the time. It showed us why he was successful. He was already a famous figure.

I remember a time when I was working in the US in the ‘90s on a very difficult problem—difficult for me at least—and was not making any headway when I went to see him. He was in Pennsylvania at that time, and I saw how hard he was working. Then I came back and that extra push made me get the solution. That’s what happened. I wrote about it in one of his 80th birthday volumes.4

I see. Seeing somebody work so hard prompts you to stretch yourself a bit more, and when you actually made it, it must have been a fascinating feeling. In ISI, your work was in probability theory. That’s also perhaps the traditional training there.

VSV: Yes. I started off with probability theory. But after my PhD in 1960, I really went into group theory. Then I went to Princeton as a postdoc.

Is that when you first met Harish-Chandra?

VSV: Yes, in 1960, But it was only for a couple of minutes. He visited ISI Calcutta in 1964. He came to visit India on a University Grants Commission tour and George Mackey had asked him to try to meet me. Because he was such a distinguished man, we were given a car, so Parthasarathy and I went and bought soan-papdi [a sweet] for him. Ranga Rao was in Madras at the time. I have written about these events as well.

Yes, you mentioned your work and he made some comment which didn’t seem very favorable, and then I think Parthasarathy told you in Tamil that…

VSV: “You handle this tiger,’’ he said, “I leave you to him.”

By this time I guess you had worked in group theory as you mentioned.

VSV: Right. I had already done some work in his own area, representation theory. Initially I worked with Varadhan, after which he went to New York, but Ranga Rao and Parthasarathy came back and we formed a group.

I guess that the famous PRV conjecture, named after Parthasarathy, Ranga Rao and Varadarajan, was formulated around this time, right?

VSV: It was made at that time when we were working. It should really be PRVV because the conjecture was originally formulated during my work with Varadhan. I have spoken in Varadhan’s 60th birthday about the circumstances around the writing of this paper, in an article called “Some Mathematical Reminiscences’’5 where I have given a clear history of it. I also explain Varadhan’s role in it.

I remember that in 1987, I think, Shrawan Kumar gave some lectures in TIFR on the PRV conjecture.

VSV: He actually generalized our result, and in the generalized form, it was called the PRV conjecture and he proved it.

I remember that he announced a lecture since he had recently proven this conjecture, and I attended it out of curiosity. It’s not always that you need to understand everything but the excitement of people around you somehow has the effect of spontaneously leaving a strong impression, like you mentioned about C.R. Rao earlier.

VSV: Yes, C.R. Rao was a big presence. He always worked very hard in terms of investing a lot of time and also sitting relentlessly. He is a great man. In a sense, I think we were all his boys. I remember in Vancouver at the 1974 ICM, Klaus Schmidt was there and we were chatting and Dr. Rao came and said “Are all our boys in?” Then he went away after some time, and Schmidt was laughing. He said, “You are all still his boys.”

It should really be PRVV because the conjecture was originally formulated during my work with Varadhan

It must have been a very endearing atmosphere he had created.

VSV: Yes, very affectionate. And it played a big role I think, as it was very reassuring and a comforting feeling that you can ask questions without any inhibition. That kind of thing in a student–teacher relation is very important.

So before Harish-Chandra’s visit you had done some work, very much in his area. Was that how you first came in real contact with him?

VSV: When I saw him first in 1960, I was in Princeton as a postdoc. Herbert Robins in Columbia invited me for a colloquium and he wanted to ask whether I wanted to meet anybody. I said I wanted to meet Harish.

Would it be spring of 1960 or in fall?

VSV: It was spring.

I am asking this specifically because, I gather from the NAS [National Academy of Sciences] biographical memoirs by Roger Howe, that Harish-Chandra had a setback in his health in the late spring of 1960.

VSV: Yeah. He was not well but I didn’t know it at that time. I came to know him much better in 1968 when I was in Princeton as a Sloan Fellow. From the fall of 1960 to summer of ‘61, I went to the University of Washington; and later I was in Courant Institute during 1961–62.

Then you went back to India, to ISI. At that time, had you desired to get back to India and work there?

VSV: Yeah, but after three years or so I came back to the US. Life was very hard in India. There were no decent facilities near the institute. Even in Chennai I was not used to such conditions. So, one day I said to myself that there is no reason I should be here. I had a few friends in America and I wrote to one of them who lived in Palisades in California. UCLA sent me a tenure offer and I came here.

And you have been here ever since, right?

VSV: Yes, I never moved.

Schmidt was laughing. He said, “You are all still his boys.”

You spent your student years in ISI, and the same wanting conditions didn’t seem to matter; but when you came out and were exposed to a better living condition, and could continue your work, you perhaps felt that there was no need to put up with difficulties. Is that the kind of sentiment that played in your mind?

VSV: Exactly. That’s the sentiment I felt—there was no need to put up with these difficulties and I could do what I do there elsewhere too. It probably means that work depends upon the people and not their circumstances or surroundings. There was not even a Xerox machine at ISI at that time. I had this feeling, when I was back in ISI Kolkata after stints abroad, when I asked myself—“Is this where I worked as a student and where I am now going to be?’’ [Laughs] After a day, I had become accustomed to it.

What were your student days like? I mean not just at the institute, but did you also move around in Kolkata? Second-hand book stalls and such…

VSV: No, no. We were in a corner outside the city. It took a big effort to go to the city in crowded buses. In those days, the public transport was also very poor.

Though you went back after three years and got accustomed to the situation after a day, when the offer from UCLA came you decided to make the move.

VSV: When you are married, you can’t expect your wife to suffer the same thing. Things had not improved much in those days, and we realised that we didn’t have to stay and suffer.

But ISI was a transformational place for us and we became mathematicians there. In mathematics you have to prove things—you have to conjecture and prove. It’s a different level altogether. It’s not like doing homework exercises, and that transition was made while we were in ISI. We worked all the time.

ISI Calcutta was a transformational place for us and we became mathematicians there

It must have been a really exciting atmosphere over there. Since ISI was running the B.Stat. course and had students, did you also have to engage yourself in some teaching and related duties like conducting tutorials and such?

VSV: Yes. I taught measure theory while still a PhD student. It was not that having to teach was a part of the duty but because at that time mathematics suffered under a neglect there. Teaching the course did help but we simply wanted to be left alone to do our work, which was the case there. We were given offices where we had no contact with anybody else—somewhere in a distant part of the building where we could shout and nobody would be within hearing distance. K.R. Parthasarathy has described the conditions at that time in the introduction to my collected works.6

In those days it seemed difficult to believe that Indians could do science. All the great Indians were first discovered by Europeans. Recognition in India happened only after you were recognized by the West. But ISI was the first place where I saw Indians moving on an equal level, solely by means of their achievement. I remember it was not so long after the independence, and we were still colonial-minded.

ISI itself was started sometime in 1931 but then things may have started to look up soon, and only after independence, since P.C. Mahalanobis had a good friendship with Nehru and that would have certainly helped.

VSV: Yes. He brought many intellectuals. The first five-year plan was being created and there was an excitement around that. On the golden jubilee of the institute in 1981, I wrote an article recollecting those times.7

Did you also see Mahalanobis around, at the time you were a student?

VSV: I saw him once. He was a distant figure. While in Calcutta he stayed in his office at Amrapali. C.R. Rao was the man who ran the place. The institute was a very corrupt place but we had to concentrate on what we wanted.

By 1962, the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) had already moved to a new campus and the facilities were really upscale. Was that, by any chance, on your map?

VSV: They were the rich cousins. They could have branched out to widen their base but they didn’t do it. They lost a big opportunity to enlarge their fields of research. For example, I think they missed an opportunity to get K.R. Parthasarathy in as part of the faculty. He is one of India’s most recognised mathematicians.

Of the four of you from PRVV, K.R. Parthasarathy is the only one who stayed back in India.

VSV: He went for a time to England, first to Manchester and then Warwick, I think, and then he came back. I think he wanted his children to grow up in India. After he came back, he soon moved to Delhi. By then the Delhi campus had arranged better conditions and so he preferred going there. And C.R. Rao too had come to Delhi. He is a favourite of C.R. Rao, just as all of us are too.

The first five-year plan was being created and there was an excitement around that

So that worked well. On a slightly different note, do you have any siblings?

VSV: I have no brothers but have four sisters. The two older ones are dead and the younger sisters are alive.

Being the only male child, and coming from a typical middle-class Indian family of that time, how did your parents take it when you moved abroad?

VSV: It was difficult for my parents. They were too old-fashioned to move out and they were both diabetic. It would have become very difficult for them as they would have nothing to do here. I loved my parents but I had to do what my soul wanted. It was not an easy decision but I managed. In time, they too accepted. I came to the US in 1965 and my father died in 1972. One of my older sisters took care of my mother, who also died six years later.

The thing is that difficulties in personal life are common to everybody and it is what you do in spite of them that matters. You have to rise above feelings of isolation, sadness and so on, to concentrate on what you want to do. You may have to become a little bit stone-hearted sometimes to do that; whether it is worth it or not I do not know but that’s how my life went.

Difficulties in personal life are common to everybody and it is what you do in spite of them that matters

Thank you for sharing about these circumstances. Moving over to another topic, you also have written a lot of books, at least ten that I noticed. Why did you feel compelled to write?

VSV: You want to share your knowledge. André Weil, for example, was not only a great mathematician but also someone who tried to share his insights. What is the use of knowledge if it is locked up? It has to be shared. Writing books gave me special pleasure because I am not a perfectionist; so it helped clarify during the process. You write and that’s it. After that I don’t worry about it.

How did the book writing happen—did you teach a certain course, make some notes systematically, and then turn them into a book?

VSV: Sometimes, but not always. Some of the books didn’t materialise from any course either. My most recent book was one published by Springer.8 where I have given more personal details about my interaction with George Mackey and Harish-Chandra.

Is that the one related to supersymmetry? And is that your current interest in some sense?

VSV: Yes. Right now I am working on a project with a former student, on algebraic geometry.

I see. You also have guided many students—17 students and 51 academic descendants is what I saw in the Math Genealogy database.

VSV: 18. I know this because my students gave me a photograph of all of them on the occasion of my 70th birthday.

You have edited a number of books too, including the Collected Papers of Harish-Chandra, with the most recent fifth volume published in July 2018. Perhaps this is a good place to dwell on your long and close friendship with Harish-Chandra, especially since you have written a lot and movingly about him, and his influence on your own work. How did it begin?

VSV: It started in 1968 when I was a temporary member in the Institute [IAS] as a Sloan Fellow and I remember asking him for some suggestions on what to work on. His reply was: “If I give you a suggestion, that means it’s my problem. But you must find your own ideas.” I think that was the best advice I have ever received.

That is to follow your own path, following on your own intuition.

VSV: Yes. Wherever it leads you.

I would imagine that’s how he himself perhaps worked, lead by his intuition and following it up with rigour.

VSV: Yes. He had a great sense of imagery while talking. He once said, “For example, if you try to read what Siegel has done, it’s a waste of time because he has taken all the diamonds. There won’t be anything for you to find.”

Was the fact that your interests had shifted to representation theory, and that you came in contact with Harish-Chandra, among the reasons why you came to the United States? Did it even remotely influence your decision?

VSV: No. He was of the very strong opinion that I should stay in India. I had commitments. My sisters had to be married and my father’s means were modest. So I said it’s alright. Charity begins at home.

He definitely advocated staying back and working in India?

VSV: Yes. And, as a matter of fact, I would have, but in Calcutta things weren’t easy. He had left India already in 1945 and went to Cambridge for his PhD, then came to the US. In between, he spent a year—1952–53—in India, but his next visit was only in 1964. So he did not quite have a realistic idea of how things were in India at that time.

“If I give you a suggestion, that means it’s my problem. But you must find your own ideas.”

Therefore when you got this offer from UCLA, you went there. Perhaps it indirectly also helped you to keep in touch with Harish-Chandra and visit him from time to time.

VSV: Sure. I came here and worked in representation theory for many years till the late ‘70s. But he had grown weak physically with a couple of heart attacks, and he died in 1983. It was too much to lose a friend and a mentor, so I changed my subject.

You suddenly felt the void.

VSV: Yes, yes.

How regular was your contact with him after you came here? There were no emails those days; so over phone and letters perhaps?

VSV: I went there a couple of summers—I think in 1970 and perhaps once again later, I don’t remember. Even though we were in the same country, distances were too far to travel often. So the contact was through handwritten letters mostly, but later on when he became more sick during the late ‘70s, we maintained contact more frequently through the phone calls. I used to call him every week to generally enquire about his health and just to keep his spirits up.

I am sure he must have appreciated it very much, because he resonated some of these sentiments in his letters that you have reproduced in the fifth volume of his Collected Papers.

VSV: He was a philosopher, and I am sure he found ways to come to terms with his conditions, as he has mentioned it in those letters. He was very clear and eloquent. In one of the letters reproduced in that volume, referring to a certain bereavement in my family, he wrote: “… it is only at such moments that we wonder about the purpose and meaning of life, groping for something more sustained and secure. Perhaps you will find some comfort in work.’’ His own work was highly tied to his emotions. I think many heart attacks can be traced to periods when he was not successful.

The internal journeys one has taken are extraordinarily difficult to capture. I remember he had a heart attack once when I was in Princeton and I knew that he was struggling even before that. His greatest achievement, I think, is the construction of the discrete series representations, the announcement of which, was already made in 1962 or ‘63; but when he was suffering he thought he had a proof. It didn’t work out and he cancelled his lectures but after the heart attack and the operation and so on, he went by another route and everything was smooth.

The intuition was right but he found a different way to prove that. Is that what you mean?

VSV: Yes. Well, I don’t know. He certainly went with a completely different proof to reach his goal and the same thing happened later on. He was working unsuccessfully on some p-adic Fourier analysis and he had another heart attack. Those days, you see, just bed rest was advised for a heart attack, and nothing else. He recovered and he asked me “What have you done today?” and I said “Nothing.” He said “I have done something” and he found a way to overcome his difficulties. Maybe the forced rest cleaned his mind and cleared off the clutter.

He needed to give sufficient time for this process.

VSV: Yes, but he was a very impatient man. In mathematics, if you prove a difficult theorem, you don’t know a priori, till you prove it, whether it is true or false. That’s why I don’t regard second proofs of already known theorems as important because you know the result is true beforehand. But when you are the pioneer, it’s like Columbus. You assumed that you will go to India and ended up elsewhere. You can never tell. These are voyages of discovery in which your mind and heart are combined because your heart wants the result to be true but your mind won’t accept it unless the proof is correct.

These are voyages of discovery in which your mind and heart are combined because your heart wants the result to be true but your mind won’t accept it unless the proof is correct

It’s very difficult to find out the well of creativity from which something pops up for an individual. You don’t know the source of a genius. You can talk about Kalidasa, for instance, on how he wrote his beautiful poetry. Coming back to Harish-Chandra, he wrote, in another of his letters to me: “It is not uncommon to have periods of frustration in research. It is a good idea to have several different channels open and to switch from one to the other when you get stuck. Also fallow periods should be used for learning. It is not helpful to adopt an obstinate attitude towards a difficult problem. When things get very tough, it is better to move on to something else. However one should keep returning to the same problem periodically over the years. Recently I had an experience of this sort with the Steinberg character about which I had thought off and on, for the last two years.” So, while he kept himself engaged in different ideas, he also kept coming back to something that he wanted to accomplish. I don’t think there was anybody who worked harder than him.

George Mostow also says the same in his talk during the memorial conference that “… no mathematician of our time has successfully completed so long and so arduous a climb, solo.’’ Coming to your interactions with Harish-Chandra, you said it was mostly through phone calls during the last years of his life; but the regular letter correspondence with you reveals some of his personality.

VSV: Semi-regular, I would say. And the important ones, in which one can get a glimpse of his thought process, have been reproduced in the latest fifth volume of his Collected Papers. He reveals his personal side in some of them. His mention of returning to explore an idea again and again in one’s pursuit also appears in a letter where he talks about the artists Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cezanne; he wrote “I have always been fascinated by Cezanne, both by his work and his personality. In his pictures he keeps coming back to the same subject in order to penetrate deeper. There are no tricks but a consistent and pervasive philosophy which enables him to explore the folds of a napkin with the same awe and respect as the folds of a mountain.’’ He had this artistic streak in himself and was, himself, a good painter.

I remember reading in some place where he says: “In mathematics there is an abstract canvas which can be filled without relation to external reality.’’ Is there any other recollection you have from the letters or discussions that you would like to share?

VSV: He wanted to go back to India but physically it was not possible for him. He had become tired and weak as a result of many heart attacks. Plus, he would not have thrived in India. The institute in Princeton was the perfect fit for him.

In the preface to the fifth volume of his Collected Papers that was published in 2018, co-edited by Ramesh Gangolli and you, you mention that after Harish-Chandra’s passing away, Lily and you went to his office, and collected all the papers; and that the volume is a collection of some of his unpublished works.

VSV: He was one of the greatest mathematicians of the second half of the 20th century and at some point perhaps one should pay homage to his work, in the sense that one should think about the ideas that he has started and explore them.

Thank you so much, Professor Varadarajan. It was truly a fascinating journey touching upon some of the defining moments of your life, work and lasting friendships.

acknowledgement

We thank Shilpa Gondhali for her help with transcribing the recorded interview.

Footnotes

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGTZYPWd3NA. ↩

- Bertrand A.W. Russell. An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry. Cambridge University Press, first published in 1897. ↩

- “A Large Deviation from the Ordinary: S.R.S. Varadhan in Conversation”, Bhāvanā. 1(4). ↩

- “Some Remarks on Arithmetic Physics”. In: C.R. Rao 80th Birthday Felicitation Volume, J. Stat. Planning and Inference. 15 Apr 2002. 103(1-2): 3–13. ↩

- In: Methods and Applications of Analysis. 2002. 9(3): v–xviii. ↩

- “V.S. Varadarajan”, by K.R. Parthasarathy. In: Selected Papers of V.S. Varadarajan, Vol 2, Differential Equations and Representation Theory, pp vii–viii. Eds. Donald G. Babbitt, Ramesh Gangolli, K.R. Parthasarathy. Hindustan Book Agency, 2013. ↩

- V.S. Varadarajan. 1983. “Mathematics In and Out of Indian Universities”. Math. Intelligencer. 5(1): 38–42. ↩

- V.S. Varadarajan. 2011. Reflections on Quanta, Symmetries, and Supersymmetries, Springer. ↩