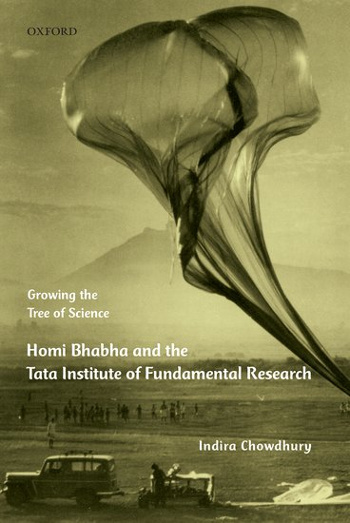

published 2016 by Oxford University Press

320 pages

ISBN 9780199466900

Apowerful man in charge of an orchard helps another powerful man plant a tree in the orchard. The story of the latter is beautifully told by the author, renowned historian Indira Chowdhury, in her book Growing the Tree of Science: Homi Bhabha and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. The man in charge of the orchard of course was Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, and he and Bhabha were close enough to call each other bhai.

“This book differs from earlier studies on institution-building practices,” writes the author in the prologue, “in that its focus remains archival analysis of documents, photographs, and oral histories with a view to understanding the social, political and cultural process of institution-building. Taking as its focus TIFR, from its foundational moment in 1945 to the moment of its founder’s death in 1966, this book tries to trace the evolution of one of the most important experiments in scientific institution building in India.” She goes on to ask: “What made TIFR unique as an institution and what did Bhabha model his institution on? The book attempts to present a history of a scientific period of this institution by analysing its practices, its networks and its culture.”

Writing institutional history based on available archival material, which at best is fragmented, and based on oral histories which are often influenced by selective memories and biases, can be a daunting task. Arriving at “true history” from such sources can easily devolve into a “triumphalist” interpretation of history, which the author wisely eschews. As she remarks, “… this book draws attention to science as practice, and what science meant to the community.” A progress report of TIFR, this book is certainly not.

The main sections of the book are divided thematically into five sections: Dreams and Realities, Science and the Creation of Elsewhere, Building a Scientific Community, Institutional Networks and Institutional Life, and the The Predicaments of Institutional Legacy. In addition, the Prologue and Epilogue must be considered integral parts of the book and its thesis.

The author describes the genesis of TIFR in the first chapter. The author considers the Saha Institute which was founded in 1949 as an institute for nuclear physics and shows the various reasons why TIFR took its present form. The Institute probably would not exist as it is today without an eminent physicist like Bhabha as its visionary, and this is also true of the Saha Institute founded by Meghnad Saha. But the fact that Bhabha was close to the council members of the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, in particular Rustom Choksi and J.R.D. Tata, played a crucial role here. Much later, his friendship with Nehru, an ardent supporter of science, brought his vision to fruition. Of course, scientists like S.S. Bhatnagar too were essential for their unstinting support. For these individuals, who occupied a rarefied space compared to the poor migrant masses of Bombay, creating an institute for fundamental research suggests a whiff of elitism, the author notes. But as Bhabha’s quote at the very beginning of the book suggests, such elitism is almost a necessity in scientific research: “This is a field [science] in which a large number of mediocre or second rate workers can not make up for a few outstanding ones.” He goes on to say that it takes at least ten or fifteen years to grow outstanding scientists, from where the metaphor of tending a tree comes from. This metaphor is further emphasized by Bhatnagar saying why he would plant a mango tree even though he might be too old to enjoy its fruits.

“What made TIFR unique as an institution and what did Bhabha model his institution on?”

At the time of the founding of TIFR, there was very little of the culture of science in Indian educational institutions. While there were premier institutions like the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore and the Indian Statistical Institute in Calcutta, TIFR was one of the first institutions founded primarily for pure science research and less as an educational institution.

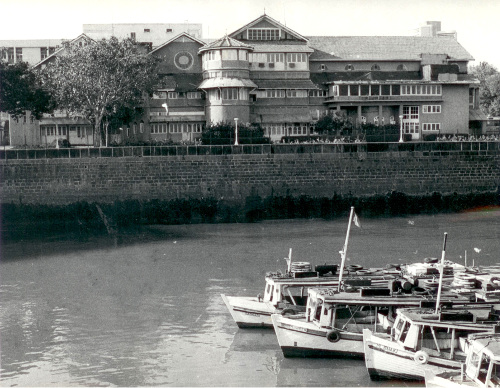

Old Yacht Club building where the Institute functioned from before moving to the present Navy Nagar Campus in 1962. TIFR Archives

The war (WWII) was raging and India itself was on the cusp of gaining independence. The colonial institutions primarily trained people to be civil servants, stressing legal and administrative studies. This attitude was to continue for decades. Many of the universities in India had no tradition of research, while Bhabha strongly felt that to inspire a new generation and to fruitfully engage with the world, the teachers must be involved in research. Bhabha was stranded in India due to the war and at first was just planning to spend his forced time productively at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. But soon, he changed his mind and started dreaming of building a “Princeton or Cambridge”, a creation of “Elsewhere”, alien to the culture of that time in India. One of the earliest and vivid examples of this attitude is Bhabha’s insistence on first nurturing a group of scientists and focusing later on a suitable edifice for the institution—this was very much against the prevailing norms. Though the Institute was founded in 1945, only in 1954 did the groundwork for a permanent structure start in Holiday Camp (now Navy Nagar), and it was later in 1962 that the building was inaugurated. It took another eight years before suitable residential quarters were built. Bhabha also felt that the administrative practices of that time were full of red tape and wasteful. He tried hard to change these in scientific institutions and though he succeeded for a while, in later years, as the author notes, it began to resemble the bureaucratic structure that was shunned by its founder.

Bhabha tried to gather productive scientists, keeping in mind science in its broadest sense, with an emphasis on fundamental research since there were already national laboratories doing applied research. One of the earliest recruits was the mathematician D.D. Kosambi, sowing the seeds of the present day School of Mathematics. Since TIFR was originally planned as an institute for physics, Bhabha justified Kosambi’s hiring to the Tata Trust by saying: “He [Kosambi] does not know physics, but the sort of mathematics he does is of great interest to physicists and is used by them constantly.”

Not all of Bhabha’s attempts at attracting eminent scientists to his nascent project were successful (including Kosambi, as we shall see soon). Stalwarts who declined included S. Chandrasekhar (who finally went to Chicago) and S.S. Chern (from China, who went to the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton). He did succeed in bringing K. Chandrasekharan who was really the architect of the School of Mathematics and who built it into the formidable centre which it is today. Meanwhile, unfortunately, Kosambi slowly withdrew into the shadows and finally quit. Though there are books ascribing this to Kosambi’s leftist views, archival material does not seem to support it. The case of Bernard Peters, a Polish Jew who migrated to the US and was lured to TIFR by Bhabha as a cosmic ray physicist, is more stark, generating a Times of India headline, “Tata Institute Expert: A Red”. In these episodes, Bhabha comes out with flying colours, reiterating that science is beyond such divisions and is universal. Bhabha wanted to attract scientists from abroad to visit the Institute or even come permanently, rather than sending younger people to be trained in the West. He had some spectacular successes and many failures. For example, Bhabha tried to attract R.P. Feynman and E.C.G. Sudarshan. Feynman humorously rejects the offer by referring to his second marriage, “I am no longer a sensible man like you”, alluding to Bhabha’s bachelorhood. Sudarshan on the other hand was probably unhappy that he was offered only an associate professorship and refused to come back from Rochester.

While the scientific achievements of TIFR can probably be fully appreciated only by a small number of people, no one who walks into the Institute foyer for the first time can be unimpressed by a mural by M.F. Hussain on the mezzanine wall. As Bernard Peters says:

A further important element in creating a lively intellectual atmosphere was Bhabha’s effort to broaden the intellectual base and widen the range of interests of the staff. For this purpose the institute library acquired books and subscribed to journals covering various aspects of human culture… original works of art, ancient and modern, were placed throughout the building and the institute played at times host to artists of highest quality (theater, music or dance) with free access to such events for the staff.

In my days at TIFR as a PhD student, even the ashtrays in the west canteen were beautiful plates created by an eminent artist, Badri Narayan from Bombay. As the author says, “scientists of TIFR were envisaged not only as leaders in an expert-led world but also as connoisseurs capable of holding conversations with the world”. About institutional culture, she writes that “denizens of such a terrain would not require a singular political identity as long as they were free in their scientific practice”.

Bhabha wanted to attract scientists from abroad to visit the Institute or even come permanently, rather than sending younger people to be trained in the West

Bhāvanā being a mathematics magazine, I’d like to focus on the story of the School of Mathematics, though it is only one of the many threads in the book. I have already mentioned that Kosambi was the first mathematician to join the Institute, that too within a fortnight of Bhabha becoming the director. Soon after, F.W. Levi, who had taken up a chair in Calcutta, joined TIFR. Both Bhabha and Kosambi were unclear as to the general direction for the School of Mathematics, and even whether it should be built at all. The decisive moment for this happened after they hired K. Chandrasekharan (KC) from Princeton, whose teacher in Madras was K. Ananda Rau, a contemporary of Srinivasa Ramanujan. Soon afterwards, K.G. Ramanathan (KGR) joined TIFR and the die was cast. Unlike in the West, there were not too many research mathematicians to hire and so they started by carefully selecting students and training them, a tradition which continues to the present day. Father Racine, a French Jesuit from Loyola College in Madras, played a role in sending some of his students to TIFR—they went on to become great mathematicians and further strengthened the School. This also partly explains the influence of the French school of mathematics. KC and KGR, who had a wide circle of internationally reputed mathematicians among their friends, invited many of them to give lectures at TIFR, for which students took notes. This trained the students in some of the active areas of research as well as inspired them due to their close informal contacts with these visitors. As noted in one of the interviews by the author, this role of a scribe, for both physics and mathematics courses, forced the students to interact with the accomplished visitors who would have been intimidating otherwise to the young people. Though KC left a short while before Bhabha’s death, the School continued to flourish. (I was hoping to find a clearer picture of why KC left in the archival material, but was disappointed that they do not exist. The author does mention reasons given by people like Jal Choksi, but I wished there were more explicit details from KC himself.) My own personal feelings about the School though, is aptly captured by D. Mumford’s description:“… the unreal mathematical pleasure dome on the Arabian Sea.”

The fact that the School was started with just a few people also meant that to broaden its reach and to cover many fields, it either had to hire many people in senior positions from outside, which Bhabha and KC felt would not be good for the morale of the younger people and students; or, as KC and KGR eventually did, not to force students to work in their [KC’s and KGR’s] areas of competence. This was an unusual practice and I have rarely seen it elsewhere.

This attitude continued even years afterwards, when the School had many senior people in several fields. When I joined as a student, another student in my group was interested only in mathematical logic. There was no one to guide him and judging him was difficult for the faculty. Finally he was judged using external experts, but it did not have a happy ending. He went on to finish his degree at UC Berkeley. My own case is somewhat tamer, but similar in spirit. While I worked in a field in which there were many experts and a majority of the faculty would have understood my work, the problems I worked on were not of direct concern to the faculty at that time. This was tolerated, if not encouraged. But my success depended on the culture built by others—the atmosphere was conducive to discussions and many at TIFR had a broad enough understanding of mathematics to sustain such conversations. In my case, the flow of visitors, in particular L. Szpiro’s lectures for which I took notes, and talks by A. Sathaye from Kentucky, were crucial in determining my future. These helped me immensely to recognize topical issues which one might be interested in. Finally, the quick communication (prior to email!) and dissemination of important results—in my case, the solution of Serre’s problem by D. Quillen—by a group of enthusiasts kept us ahead. The confluence of all these can not be coincidental, but must have been carefully planned for years by KC, KGR and others, and I was one of the thankful many who ate the fruit from this lovingly tended tree.

This is a deeply researched, and a carefully written book. It also comes out at an important time, when India is building multitudes of new scientific and educational institutions, like the new IITs and IISERs. This book holds many important lessons for the builders of these new institutions. Though the author herself is not prescriptive, let me mention a couple of points we should take away from the building and success of TIFR as described in the book. One is that pure science institutions are better built around a few stalwarts in their fields. Second, training the younger generation to carry the mantle of such institutions is superior for the health and morale than recruiting large number of people from outside.

Finally, this book is dedicated to the late Veronica Rodriguez, who I would consider a personal friend, and am sure would be pleased with the book. Reviewing this book gave me the great pleasure of walking down memory lane, and up the path of nostalgia. It may be unusual to dedicate a review, but if I may, I would dedicate it to one of the first persons mentioned by the author, M.B. Kurup, the late Dean of Physics at TIFR and a very close friend of mine. His inadvertent request to the author to relieve him of a trove of documents from his office led her to some valuable archival material for this book. Institution building as well as recording its history involves a lot of careful thought and planning, but serendipity plays a role too.