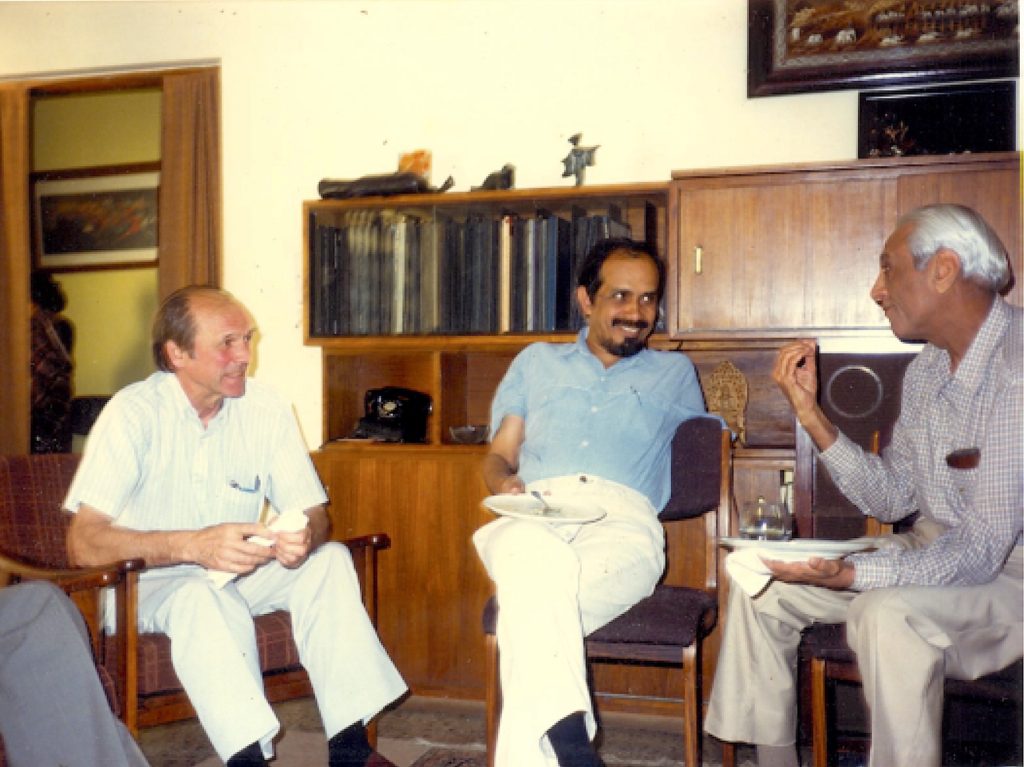

Few knew Satish Dhawan as long and as closely as Roddam Narasimha, National Science Chair Professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, Bengaluru. Narasimha interacted closely with Dhawan first as his student, and then as his colleague at the Indian Institute of Science. In this interview, he recollects the profound and lasting influence Dhawan had on him and others, as well as how Dhawan transformed IISc–-of which he was the longest-serving Director–-and ISRO.

When you first arrived at IISc as a student, was Satish Dhawan a faculty member in the Department of Aeronautical Engineering?

RN: I came here in 1953. He joined the Institute in 1951 as a Senior Scientific Officer. He had his PhD degree from what was one of the two great centres of aeronautical science research in the world then, namely Caltech. Then he had a research record at Caltech which you couldn’t beat, so he quickly became an assistant professor. And when I joined here in 1953, he had already started setting up a high-speed aerodynamics lab in the Department, and a boundary layer lab which was near an old low-speed wind tunnel.

After you did your diploma in aeronautical engineering, did you leave immediately for Caltech?

RN: No. After my diploma, I stayed for two more years here. Before I got it, I was wondering what I should do, and Professor Tietjens, who was a well-known German scientist, was the Head of the Department at that time. He was usually a serious man like German professors tend to be, and he wanted to see me just before he was leaving. He almost never did that sort of thing, so I had a little trepidation about what he wanted to say. He asked, “What are you going to do after here?”, and I said “Well, I don’t know. There is industry. I also like the atmosphere; I might apply to the Met Department. I am not quite sure yet.” He said, “You should go abroad and you should do research. Go either to Göttingen or Caltech. If you decide to go to Göttingen, write to me and I will make sure that they will admit you.”

As I was thinking about this, Dhawan came along. I had already helped him in part with the design of the supersonic tunnel. He also asked the same question as Tietjens: “What are you going to do next?”, and I told him roughly the same thing. He said “Why don’t you stay here and do some research before you go abroad?”. It sounded like a good idea to me because I wasn’t really familiar with what research implied. So I stayed here for two years doing the associateship, with Dhawan as my supervisor.

I believe that one of the wind tunnels that Dhawan built is still here in the Institute.

RN: Yes, when I came here as a student, Dhawan was working on this supersonic tunnel. It had an interesting test section, one inch wide and three inches high. It was a very small tunnel but it could make experiments on aerofoils, for example, and show shock waves on them at supersonic speeds. It measured pressure distributions but did not have a wide variety of Mach numbers. One of my first assignments from Dhawan was to design nozzles for this tunnel, and I spent around three or four months making nozzles for different Mach numbers so that you could see how things varied with the Mach number. What struck me was the instrumentation on that tunnel. We didn’t have a lot of instrumentation but what we did have had been very cleverly designed by Dhawan. For example, he wanted to measure the pressure and the temperature in the tunnel. We couldn’t buy the commercially available instruments which measure small currents, so we had a galvanometer instead, like in a physics lab. It gave the whole setup a strange mixture of science and engineering and that I think was his attitude–-a philosophical attitude. One must remember that Dhawan had a degree in physics as well as in mechanical engineering.

And a degree in English literature…

RN: You are right. So he had a very broad education. I once asked him why he took English literature. He said, “First of all I liked it and secondly it gave me more time for playing tennis!” He had this mix of science, engineering and literature in his background, and in his education. He quite often did what physicists did in an engineering lab and, to young students like me, it already started erasing the boundary between the two. And of course, aeronautics depended on a lot of physics. I would say that among the different branches of engineering, it probably makes more demands on physics and mathematics than most of the others. So it had that challenge. It was at the same time both a scientific and an engineering challenge–-for example, turbulent flow. That certainly is what appealed to me and what must have appealed to Dhawan himself. He also had decided to do aeronautics when he went abroad.

Anyway, my conversations with Dhawan and my experience working with him settled for me what I was going to do. I enjoyed doing it. I still remember taking readings in that small tunnel. There was also another tunnel, 5 by 7 inches. This tunnel was being built when I was a student. Some of the pieces of hardware were there but it took a little longer before the tunnel was completely built and could be used for research or development.

A couple of years after I left in 1957, the Government of India decided to build a National Aeronautical Laboratory, NAL. It started first in Delhi but eventually moved to Bangalore. They had a big piece of land but with no buildings or anything–-so they occupied the Maharaja’s horse-less stables. They were looking for people and the first few who went there were those who had experience with supersonic flow in Dhawan’s lab. As NAL labs came up in their own land, a lot of studies for the wind tunnel to be built at NAL were made by students from the Institute who got jobs at NAL.

So there was a close relationship at that time between the Department of Aeronautical Engineering at IISc and NAL?

RN: Very close. Apart from those IISc students, there were very few in India who went to NAL with a knowledge of supersonic flows and gas dynamics in general. There was also a course in gas dynamics at IISc, taught by Dhawan himself. So when the lab [NAL] opened in 1959-60, quite a few of the people who joined had worked here at IISc. HAL [Hindustan Aeronautics Limited] also started designing a supersonic aircraft, the HF-24. They also wanted people who knew some gas dynamics. So all of a sudden there were more jobs than people and so things grew very fast in the late ‘50s and ‘60s.

The 5-inch by 7-inch tunnel at the Institute had a size where you could get some skill and knowledge that would be directly useful in building a 4-foot by 4-foot trisonic tunnel that NAL was planning. A lot of it was actually built in Canada but there was a good team of engineers who went from IISc and looked at a variety of problems that they had to carefully monitor for the tunnel to be able to operate, and so it was a really important contribution at that time.

Thus Dhawan did all the groundwork, so to speak, for the tunnel which came up there and a few other facilities. Those who joined NAL went on ahead and built their own smaller tunnels too.

You were saying earlier that the two years you spent after your diploma at IISc with Satish Dhawan were the two years which convinced you that aeronautical engineering is what you should do. Could you tell us about your research?

RN: Yes. Well, there were two things. Research projects had started at the Institute, but at that time, only low-speed wind tunnels were available. There was a 5-foot by 7-foot tunnel but it was structurally integrated with the rest of the building, so you couldn’t move it around like these other tunnels. Dr. V.M. Ghatage–-the first Head of the Aeronautical Engineering Department, and a student of Prandtl–-had built that tunnel and made some simple measurements using it. Then when HAL wanted him to set up a design group for them, he left IISc on leave.

That 5-foot by 7-foot tunnel had difficulties because it could give seemingly awkward results on important variables, for example the drag of the aircraft, making the test results doubtful. The tunnel flow speed was just in that very awkward range where the flow on the test model could be either laminar or turbulent, and extrapolations about what happens in flight would become unreliable. So, while a much bigger and better tunnel, 9-foot by 14-foot, was getting built, the space near the test-section of the 5-foot by 7-foot tunnel became part of Dhawan’s boundary layer lab. A 20-inch by 20-inch boundary layer tunnel was built in that space, and Dhawan decided that we should study transition to understand the “awkward” results from the 5-foot by 7-foot tunnel. He gave that as my research problem, and we went ahead and started making measurements in the 20-inch boundary layer tunnel.

I learnt a big thing from Dhawan: it could be done in India

Just at that time, the thinking about how transition from laminar to turbulent flow occurs in a boundary layer had begun to change. The earlier view was that you had laminar, soft regular flow, and there was a very jagged front which separated it from the turbulent flow on the downstream side. This jagged front moved back and forth in space, and made the flow very intermittently turbulent in a certain finite region.

The new idea was that that’s not the way it happens. There are spots of turbulence born all over the surface, and they grow and mix with each other as they go downstream and make the whole flow fully turbulent. This picture had been proposed by Howard Emmons, a professor at Harvard, but nobody had convincingly demonstrated it experimentally. When I was starting my research, a set of beautiful experiments with very detailed measurements, made by a group at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS)–-one of the best aerodynamics labs at that time in the US–-showed that this picture was right. So just as I was beginning to make experiments here in Bangalore, the jagged line theory had to be given up and the spot theory accepted, and the flow in the transitional region as the spots were growing and mixing was intermittent. And the intermittency \gamma–-which is the fraction of time the flow is fully turbulent–-increases from 0 to 1 over that transitional region.

So this was after you completed your diploma?

RN: Yes, I was a research student and my apparatus was just beginning to work with a homemade amplifier. The NBS report showed that the Emmons picture was right, but did not compare the measured \gamma with theory.

I went back to Emmons’ paper and compared the predictions he would have made with the measurements of the NBS group, and found that they did not agree. Here was a crazy situation where the physical picture agreed with what was observed but the intermittency distribution did not, which was not mentioned in the NBS report. After a few months of worrying about it, I found out that the problem was about where the spots were born. Emmons thought they were born with equal probability all along the surface. I showed that the measured \gamma distribution implied spots were all born at one station–-the opposite limit, so to speak. By then I had our own experiments, which also confirmed the conclusion.

Around that time, there was an Indian visitor just back from a US visit, after a PhD acquired in Europe. When I told him what I was doing and the problem with Emmons and the NBS data, he just did not believe it, and dismissed my views–-Emmons could not be wrong.

But as the new hypothesis agreed with the measured \gamma, Dhawan saw its significance, and so I wrote a little note at that time for the Journal of Aeronautical Sciences. After many more experiments and analysis, Dhawan and I wrote a more detailed joint paper on the consequences of the assumptions in terms of what’s happening to the whole flow. Measurements made in the whole flow had found some strange things. For example, the skin friction–-the shear stress on the wall of the plate–-had a maximum value not where it became fully turbulent but earlier! The hypothesis of concentrated breakdown provided a simple explanation for this result.

The paper appeared in the just-founded Journal of Fluid Mechanics in 1958. And my doubts about proceeding with a research career disappeared. Furthermore, I learnt a big thing from Dhawan: his own hard work showed it could be done in India. Of course, most people used to think in those days that that would be very difficult, which was, in fact, true in a sense. At that time our budgets were small and the system of supporting research was hardly there: we had to do with whatever money there was in the Department. But we had excellent mechanics, and that was a great help. I cannot forget J.A. Doss in the machine shop, where anything mechanical he made on those old machines was magically precise and attractive. So much so that a Cambridge postdoc, David Tritton, who was on a three-year visit to our lab, was amazed at Doss’s extraordinary skills. Before leaving he had Dhawan’s permission to get Doss to Newcastle on a three-year visit to help in building a new lab there.

So my view became firm about what I should do and where. My confidence went up when Kurt Friedrichs, a famous mathematician, came from the United States to lecture at TIFR, I believe, and came to Bangalore for a visit to our lab; and after talking with him, Dhawan left him with me, as he did with any scientist visitor. I told Friedrichs what I was doing. He had never heard of it before, and was not aware of Emmons’ theory. So he seemed amazed at first that somebody so far away was saying that one important part of the picture was different. He spent an hour with me. The first half-hour I was telling him what I knew and he didn’t know. In the second half, he was asking me questions that I could not answer. So I saw that he was a very bright man who immediately picked up what was going on, and he would ask me, “Has it anything to do with stability?” I didn’t know. “How do these patterns form? What are the edges like?”, and so on. But it was–-once again–-a turning point for me; both of us enjoyed that piece of research, and I could forget the Indian “expert”. And those two papers we wrote are to this day often cited.

What are your memories of Satish Dhawan as a person outside the classroom, outside your academic interactions with him?

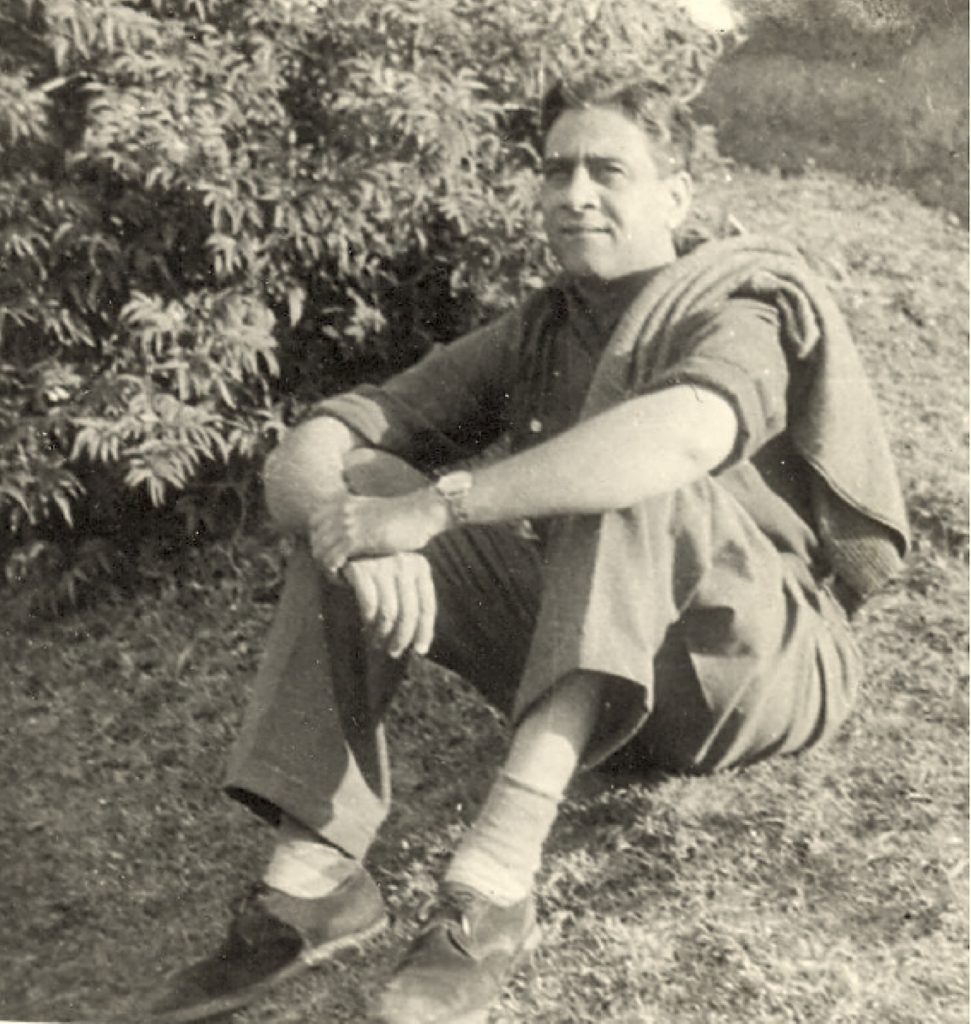

RN: Well, they are almost uniformly pleasant. He would now and then take me to his house when he was a bachelor, with just one cook who was supporting him. Dhawan would tell me, “Come let’s have a cup of tea”, and then we would go to his home and chat about various things including some science but other things too. The faculty at the Institute in general at that time tended to be serious in their speech. Most of them wore a coat and tie, and while some of them did mix with students, it was never at the level at which Dhawan did. Dhawan was very informal and very cheerful. He always had a smile on his face and he made you feel at ease, but if you thought that he was only that, you would be very mistaken. He worked very hard, and I remember friends in the hostel telling me that light would be burning in his office well past midnight. He wanted to give notes to students to help them, and took all his work seriously. But the rest of life was informal for him. That was something very unusual on the campus at that time, especially for a new Head of Department who had taken over soon after Professor Tietjens left. He was a little shy about certain things, but otherwise he was a very pleasant person to talk to. He was also serious about the country. He was a real patriot. Patriotism was never a badge for him but came through by the way he behaved and by the things he did. He thought India should be doing a great deal more, and so put everything that he could do into pushing aeronautics formally and informally.

Patriotism was never a badge for him but came through by the way he behaved and by the things he did.

Did this philosophy of wanting to do serious research but also wanting to do something that would be of use directly to the country inform his work when he took over as chairman of ISRO?

RN: Oh yes. I think that was his philosophy throughout: indeed it was his philosophy even when he was only an academic. But he did not do the same thing that industry did. Our objective here was still to understand those problems that bugged the industry at that time, especially when the bugging was because we did not understand what was going on. Thus what I did, for example, could be considered basic research but it was inspired by a real problem; and many of the problems that the students did later on were also similar. They were inspired by something or the other in the country but you tried to go to the heart of the matter: it was a combination of science and technology which I think he inherited partly from his background and education and partly from the philosophy at Caltech, which manages the Jet Propulsion Laboratory for NASA. That Caltech philosophy was the perfect match for him. He went there with a degree in science and engineering and saw a lab there which did both science and engineering. The faculty sometimes had physicists; his advisor, Hans Liepmann, was a physicist. There were also mathematicians on the faculty in the department. So they made a mix of science and engineering, and I think he brought that principle here too, which suited his temperament and philosophy.

In the problems that students after me took on, there were similar motivations. For example, there was an intake problem on the HF-24. That involves a three-dimensional boundary layer, and not too much was known about it at the time. So he started a project on three-dimensional boundary layers, and his last student, T.S. Prahlad, got a PhD for a thesis on the subject.

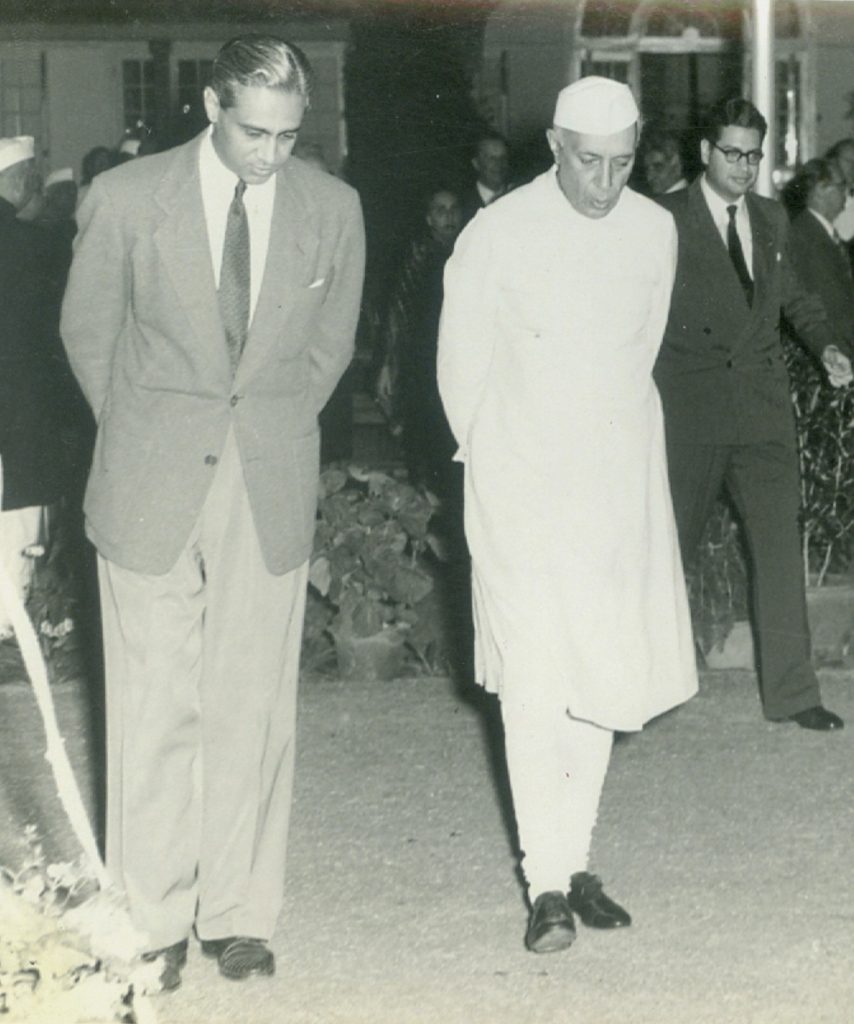

That was the kind of assessment by Dhawan of what needed to be done. I think it is an attitude which is not as common today as it was in his time. Today many would like to have problems that can bring you the most publications. Of course, publications were important even then, but not all-important. What one did for the country was also very important, in those early years after Independence. Jawaharlal Nehru was a big supporter of science and technology and Dhawan welcomed it, as everything seemed to be expanding and the country was taking on bigger problems. So Dhawan was just the right man at the right time. At the same time, he combined it with pleasantness and a sense of humour which was unusual on the campus in those days. He rarely put on a tie, often wore colourful Californian shirts, and drove a little red convertible MG in the morning from his home to the lab and back. He introduced a new personality to the campus, professionally as well as personally.

In his legacy as chairman of ISRO, how would you say he differed from Vikram Sarabhai? Did he bring something new to ISRO which made it the success that it is today?

RN: I think the space programme as it is organised and managed today is very largely the work of Dhawan. Sarabhai was the pioneer who, ahead of his time in India, started a space programme with a strong scientific flavour–-for example, studying the physics of the huge electrojet which flowed at a height of the order of 100 km in the atmosphere over Kerala. So the seed was sown by Sarabhai, but the sturdy tree that you see was largely the work of Dhawan. Both Sarabhai and Dhawan were very busy men, but they were busy in different ways.

The space programme started in the atomic energy labs at BARC [Bhabha Atomic Research Centre] when Sarabhai was the Chairman, but he passed away at the end of 1971 before he could see it grow. It then fell on Dhawan, who was at that time on a sabbatical at Caltech, returning to research for a year of change. Dhawan was invited to head the space programme and when they asked him, he said he was committed for that academic year. So Professor M.G.K. Menon ran the space programme for a short time. But he was also running the atomic energy programme, so he felt the two had to be separated. They decided that a Department of Space and a Space Commission should be set up.

Dhawan was just the right man at the right time.

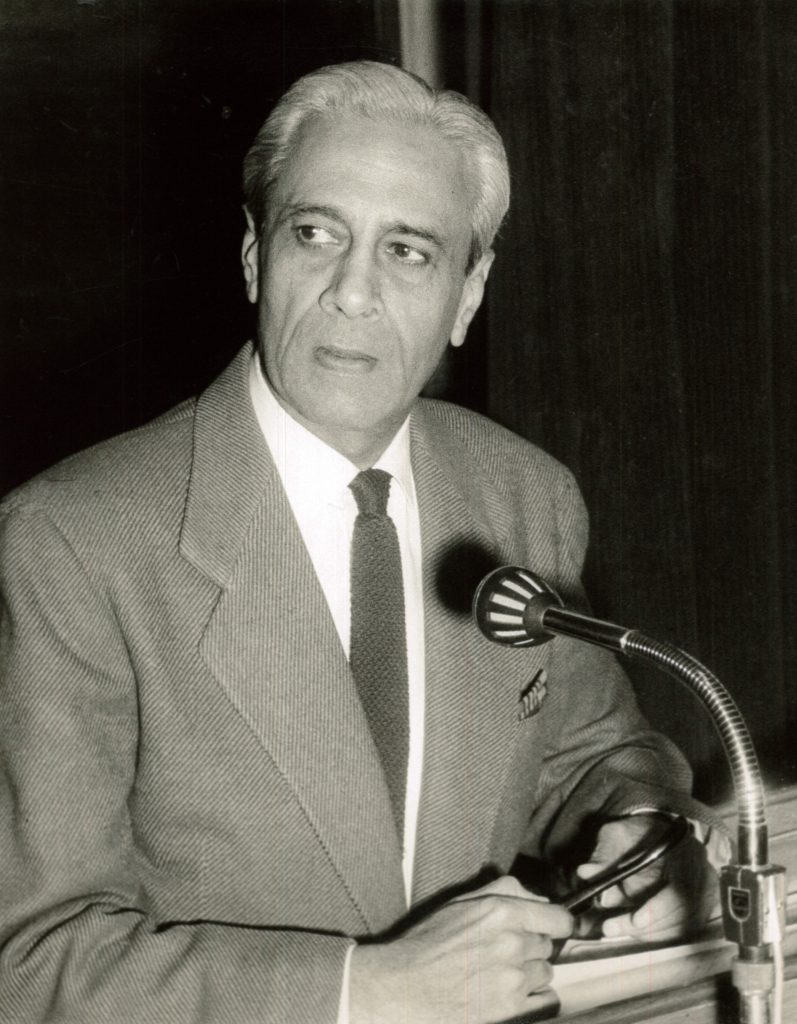

In response to the invitation he had received from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Dhawan apparently wrote a letter to her, which described some of his ideas. Nobody seems to have seen the letter, but there has been much discussion about it. For example, he felt that the space programme should have nothing to do with defence: it should be all for peace, and the development of India and its people. He felt it should not be in Delhi, but in a place with many centres of R\&D; and so on. He also said he could not leave the Indian Institute of Science, so ISRO headquarters would have to be in Bangalore. He set them down not so much as conditions but as his vision of what the space programme should be like. I have heard that he ended the letter by saying that if his proposals were acceptable to the government, he would be honoured to accept the PM’s invitation.

Both Professor Menon and the PM’s adviser Mr. P.N. Haksar were convinced that Dhawan would be the best choice because of his abilities and his moral integrity. And the prime minister agreed. Shortly thereafter, he was running two organisations at the same time, but he always took his salary only from the Institute, except for the one rupee or so he got from the Government that made him a government servant. I think the architecture of the organisation of the space programme you now see–-all those different centres and their well-defined projects–-were really the work of Dhawan, if only because Sarabhai didn’t have the time to do it. But I also think there were a lot of lessons that Dhawan learnt about how these programmes are managed in the United States and modified them, revised them, and made them appropriate for India. It was, for example, entirely a government affair when it began in India. His vision included the centres, the people who were picked to run those centres, the way that the responsibilities were divided, and the project system. Everything was defined as a project or a mission, and critical reviews were arranged for the projects with help from experts outside ISRO, including academics. All of that system was Satish Dhawan’s creation. If today most people in the country look upon ISRO as the one organisation in government which delivers, it’s because of the spirit that Dhawan inspired in ISRO staff. In a recent survey of millennials in Bangalore about where they would most like to work, the top 15 in the list had only two Indian choices: ISRO, at \#5, and Tata Consultancy Services, at \#15. That a public sector organisation is the best Indian choice, with salaries much less than those in foreign or even Indian companies, is a great tribute to ISRO and its leaders.

Dhawan had great confidence in Indian talent.

I must say that one part of this preference for ISRO comes from the fact that Dhawan had great confidence in Indian talent. Now, that is unusual. When, for example, the SLV [Satellite Launch Vehicle] project was initiated, Abdul Kalam was made the director of the project. This came as a big surprise to his colleagues in ISRO and to the scientific world in general. Kalam had only a first degree from the Madras Institute of Technology, nothing else at that time. And he had rarely been abroad. I still remember how many of my colleagues at IISc were betting on his failure. Then there was Dr. Brahma Prakash, Professor of Metallurgy at IISc, who joined ISRO to head the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre. A professor from TIFR, Devendra Lal, went to head the Space Applications Centre at Ahmedabad. So he had the best people in charge of all the centres that he set up. These were scientists and engineers who knew the importance of carrying out reviews and had solid academic and scientific backgrounds. In the initial stages I think this was absolutely essential.

I still remember the first big review they had of the SLV-3 project, with Kalam as the director. The number of people involved in that review was something like 250. It was held in an auditorium and I wondered why. Instead of a small committee room where the department heads could gather, discuss and decide, Dhawan had the review held in an auditorium. He wanted everybody to know–-the mission of the space programme and the project should be understood not just by scientists who led the project and the leaders and the centre directors and so on, but by every engineer involved in the project.

Kalam, of course, did not have to be taught about treating everybody as an equal, although he was himself a very remarkable man. But I remember that in his presentation there was a young person at the back who asked him a question. Somehow Kalam must have thought that it was not relevant, and he made what might be considered a slightly dismissive reply, although I don’t think that was the motivation for his reply at all. But Dhawan was categorical. He was sitting in the front row and said, “No, no, no! Please answer that question.” Kalam did that, and I think the message went through. Everybody knew that if it came to a technical discussion, they were all equal. It did not depend on rank or hierarchy.

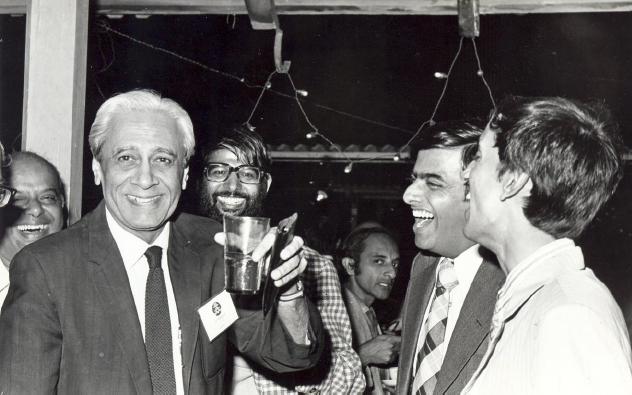

So all these principles have constituted what people now refer to as the ISRO culture, a unique culture; and in some ways, I think it was the greatest contribution that Dhawan made. It went along with his personality–-being informal, treating everyone equally–-you might think of it as a certain variant of socialism. At the same time, you have to be able to take decisions. That was always taken by a small group of leaders in the light of the reviews. So decisions were eventually taken at the top, but most people in the organisation learnt to see that it was a transparent process. Many people had a say in what it should be. And therefore I think there is a commitment to that system in ISRO, which is remarkable for a government organisation.

While he was director of IISc and chairman of ISRO, did he also have a role at NAL?

RN: Not quite at that time. He did have a role in the early years of NAL, as a member of its Research Council. The first Research Council of NAL had J.R.D. Tata as its chairman and JRD was, of course, a man who believed in the development of scientific and industrial research. Dhawan was a member and so was Dr. V.M. Ghatage. He did continue for quite some time but in 1984, when he had just retired from ISRO, he became the Chairman of the Research Council. I think he continued from 1984 to 1993. That was of course from one point of view very good for NAL because Dhawan always had worked on projects in aeronautics too. During his ISRO years, he couldn’t spend too much time on aeronautics. He was the Chairman of the Research Council when I became the Director of NAL. We had very similar views about what should be done. I would say that our period at NAL coincided with a certain boom in aeronautics, chiefly because of the LCA [Light Combat Aircraft].

What was Dhawan like as a teacher in the classroom?

RN: Well, what struck me when he came for his first class, for example, was that he was the only faculty member who came to the lecture hall smiling. “Good morning,” he would say with a big smile on his face. Others were not that way at all and, as I said earlier, he didn’t wear a tie or suit. His coloured sports shirt matched his spirit and he took pleasure in making things simple. I think the students absorbed a great deal more from his teaching than that of the others. The other thing he did was passing around a number of data sheets apart from the lectures that he gave. He didn’t spend the lectures on the details about the numbers and so on. He would derive the results and pass on data sheets with some numbers to help in calculations. He would work late into the night getting his data sheets ready for the next day’s lectures. He took it very seriously and was certainly one of the best teachers in the Department. The only man I would compare him with is Tietjens, except that he was in many ways very different in character from Dhawan. But he was a good teacher in his own way and I could see the contrast between the two. For Tietjens, every man who graduated from the Department must have his fundamentals sound. Dhawan did talk about fundamentals but not with the same emphasis, but he was a conscientious teacher and helped students a great deal. He always answered questions, and even when he conducted oral exams he was pleasant. It did not necessarily mean that you got very good grades! So they [Dhawan and Tietjens] were very different in their character but both had somewhat similar objectives, such as that all students in the lecture hall should learn the fundamentals of the subject.

When you left IISc, you joined Caltech for your PhD. Your PhD advisor was Hans Liepmann who was also Satish Dhawan’s advisor. Was Dhawan instrumental in your choice to go to Caltech for PhD?

RN: In a sense, yes. But even before Dhawan, Tietjens had told me something similar, as I have already mentioned to you. Of the only two good places in the world for pursuing aeronautical sciences, Göttingen was unfortunately not so deeply involved in aeronautics at the time because of the conditions that Germany had to sign at the end of the war [WWII]. The second was Caltech, which I saw as having an infusion of a Göttingen-type attitude into the United States. That was partially because the first Director of GALCIT1 was Theodore von Kármán who was also a Göttingen product. Although he was Hungarian by birth, he was really in many ways German by education and culture.

So at the end of my two years at the Institute, I finished my research and it had gone very well at least as far as I was concerned. I learnt a great deal from it, and I think Dhawan felt so too. He said–-once again it was very characteristic of him–-“You know, I have taught you everything I can. Now you must go abroad. Why don’t you go to Caltech?” I thanked him, and he recommended me to Caltech. I had applied to two places, one was Harvard and the other Caltech: Harvard, because that’s where Emmons worked and I had just followed him on his theory of spots but not on where they are generated. Somehow it did not strike me that it may not be the best place to go to, as some of the things I had done in my research indicated that our theory was rather different from his. But those considerations somehow did not occur to me at all at that time. I did get admission to Harvard but didn’t get any assistance, whereas I got both assistance and admission at Caltech.

I must say that at Caltech they valued Dhawan’s opinion enormously, partly because they knew Dhawan as a very conscientious and completely reliable person, who would always tell the truth. They had great respect for his opinion, and I was immediately accepted. Incidentally, I was not somebody who was terribly keen on going abroad. It may come as a surprise to many people here–-now certainly and even at that time. Some of my own uncles had said even after I did my diploma, “Why are you wasting your time doing research at the Institute? You know Dhawan well so if he recommends you, you will be automatically admitted to Caltech. So you go ask him for a recommendation.” Now I didn’t want to do it for two reasons. I didn’t like to ask for recommendations and I also was not absolutely sure that I could do research, although I liked it; furthermore, in my younger years I had formed a “Cronies’ Club”, which was inspired by leaders like Gandhi and Nehru, so we thought we should stay in India and do our work here. But those four years with Dhawan eliminated those worries.

He always had a smile on his face and he made you feel at ease

I went to Caltech as “Satish’s boy”. I was the first student who went from here after Dhawan had left Caltech–-six years earlier. I went there on his recommendation and also with the knowledge that I had already done some work, and that it involved significant experimental and theoretical components. I think I sort of walked in and it was entirely because of Dhawan.

Dhawan was the Director of IISc for about 20 years from 1963 to 1981. What role did he play in giving IISc the shape that it has today with its research programme spread across the 40 odd departments and is seen as a leading research institution not only in India and Asia but the world as well?

RN: I would say that he transformed the Institute. And I was there, seeing the transformation as it happened. When I went there as a student, the Institute had a certain structure in which some departments were very active in research and others were not. But the war [WWII] and Independence had changed the needs of the country. Dhawan saw the need for transformation, for doing things which we were not doing–-for example, theoretical physics, ecology, atmospheric science, etc. In all of these, Dhawan took a big initiative. He did another remarkable thing, namely getting the best scientists to IISc. So he was the one who invited C.N.R. Rao to come here, and G.N. Ramachandran as well. He invited George Sudarshan too–-before that there was no theoretical physics on the campus, only experimental physics. All three of them had independent centres they headed, and changed the atmosphere on the campus.

So that was how the Centre for Theoretical Studies was set up.

RN: Exactly. Sudarshan was invited to run that programme. With these changes, the tone on the campus changed. I think, therefore, academic levels at IISc went up and engineering departments also became more important. His interests were very wide, partly, once again, from his background of degrees in physics and engineering. He wanted to see that everything important in science and engineering had its place. Even the older departments changed beyond recognition, I would say, because of what he did. He got very good faculty to come here. When I came here as a student, a common joke about the Institute was that it was a bunch of labs built around the Gymkhana. While some people worked extremely hard, there were quite a large number of others who took it easy. I knew faculty members who would go to play tennis at 3 o’clock, and then take their tea and go home. All of that stopped after Dhawan took over.

I once had a proposal for him. I went and said that the monsoons are the biggest problem in India but there is virtually nobody studying the subject. It ought to be, in academia, a fundamental problem. How is it that we are not looking into it? That’s how the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences slowly came up.

ISRO is not run only by IIT graduates and foreign PhDs but also run by those who have gone to other engineering colleges in India.

The thing that I learnt from my experience at the Institute is that, first of all–-and this was important for me personally–-good research could be done here in spite of all the disadvantages. I am not saying this was a perfect place, but it had several advantages and, in some cases, the advantages were bigger than we tend to think. If you go join a US university as an assistant professor, you are not tenured first of all until you spend some time there, and, usually, you have to obtain support money by yourself. Most of them spend a year or two writing project proposals because they could not take a student unless there was support through some project. Here we are in India, where we did not have anywhere near the kind of money that GALCIT had. On the other hand, if we had a bright guy here, we did not have to ask him to apply for money, because there were few funding agencies at the time. If his record was good, he would be supported by some endowed scholarship in the Department, but it was meagre. It takes a big burden off you and you could start your research programme with whatever little support in men and money you could get from the Head of the Department. I know from my experience with some of these people that they’re as good as anywhere else in the world. It is that the system is different. The problem is not a lack of talent, but a system that does not know how to manage it.

This is incidentally one thing that Dhawan also had appreciated. One of the reasons for the space programme’s success was that his faith in the ability of Indian scientists in India was very high. He knew that because he knew the standards at Caltech too. He came to the conclusion that it’s the system–-a conclusion which I had come to independently. Later on, I began to relate it to what he had done. If he had no confidence in people here, he would not have put Kalam at the head of the SLV project. ISRO is not run only by IIT graduates and foreign PhDs. It’s also run by the people who have gone to other engineering colleges in India. But the engineering colleges don’t know how to identify this potential and how to promote it. And they have old-fashioned views about marks and courses and so on. But even that system has again and again produced, from unknown places, some excellent scientists and engineers. Kalam is one example: from a poor family in a small village and only a first degree and no publication to his credit; but he was elected to the Indian Academy of Sciences. I remember the discussion in the Council, where virtually every member was not for Kalam’s election. Dhawan had been silent, till the President asked him, “Satish… you are silent. What should we do?”. “Elect him,” he said. And Kalam was elected without another word.

Now, these are the people who have so much drive and passion that in spite of the system they manage to succeed. And Kalam went very far indeed–-all the way to Rashtrapati Bhavan, showered with honours from PhDs to the Bharat Ratna. Imagine how many more people there must be in India who can do that if they had more encouragement.

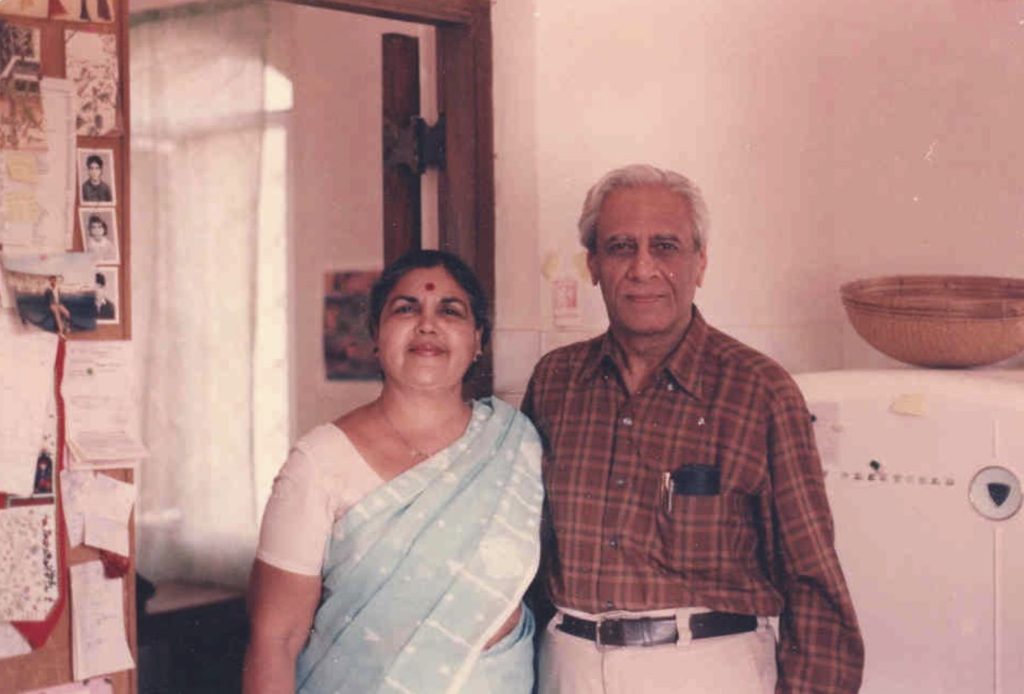

I think Dhawan was very aware of this. He was very broad-minded, with a certain socialist view, which was not the more militant type but just believed that bright and spirited people could also come from the countryside. It was for him something to practise, and not just something to argue about with governments and politicians. One example which both amazed me and induced laughter was when he took me with him to his sister’s house in Delhi. I was already working for the Space Commission at the time, and he was just about to retire from the Institute. He asked his sister, “We are selling that house, aren’t we?”,2 and she said yes. “You know I will have to quit my Bungalow at the Institute and I don’t have a house. I want to build a hut for myself,” he said. “It costs about 20 lakh rupees. Do you think you could sell the bungalow for 20 lakhs?”. She burst out laughing. “Satish, you had better learn about the real world. That house is worth some 50 lakhs. We should sell it for 50 lakhs.” He said “I don’t want 50 lakhs; just give me 20 lakhs.” That was his view. And he built a home for himself, not too far from here. Nothing fancy, nothing that was making a loud statement, but a very pleasant home.

There was actually a socialist club in Bangalore at that time, of which Professor A.R. Vasudeva Murthy was a member. He was in the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry, and a good friend of Dhawan. Similarly, there were one or two other people, like D.D. Kosambi in Pune. They used to hold small meetings here among themselves. Now, Vasudeva Murthy was a very conservative Hindu Brahmin but he was also one of those who believed that quite apart from all of that, they should also promote socialism. He combined Sanskrit and socialism, as Kosambi also did. So it was a very interesting group and, as I said, Dhawan lived a true socialist life.

He was also, I believe, president of the Bangalore chapter of the Indian Scientific Workers’ Association.

RN: Exactly. He was. Vasudeva Murthy was also involved in it.

So there was that side of Dhawan. Not only did he get the best people as faculty and students, but also transformed the Institute, its curriculum, its approach to research, its relations with national industry, and so on, sharing the dream of people like Nehru and others who had fought for it all along. They were friends of science. What the Institute today is–-like ISRO–-largely what he left behind. Other people have later made other big changes but I do think all that became possible because of the changes in attitude that Dhawan had brought about in his 18-year directorship at IISc.

Would you say that Dhawan was a man of the times in the sense that he embodied post-independence nationalism and was also quite modern in his outlook?

RN: Yes, absolutely correct. He had that modernism, and he also had a certain respect for Indic views. Look at his friendship with Vasudeva Murthy and Kosambi, both Sanskrit socialists. He knew that I had a certain interest in Sanskrit and philosophy, so he once asked me, late in his life, “You know Narasimha–-I never learnt enough about Indian philosophy but I know that you keep looking at it. Can you recommend a book where I can get the fundamentals in a short time?”. I said “Yes, I will give you the book I learnt from.” It was by Hiriyanna, a professor at Mysore University, who wrote a book called The Essentials of Indian Philosophy. It’s a very well-written book; no wasted word, no prejudices, and wonderfully clear. It tells you about the spectrum of Indic beliefs: not just the Vedas and Upanishats, but also Buddhism, Jainism, etc. So Dhawan knew what was lacking in his background and wanted to learn about Indic thoughts and philosophy. And sometime later, I was pleasantly surprised when he mentioned Vedic thought and philosophy in one of his speeches.

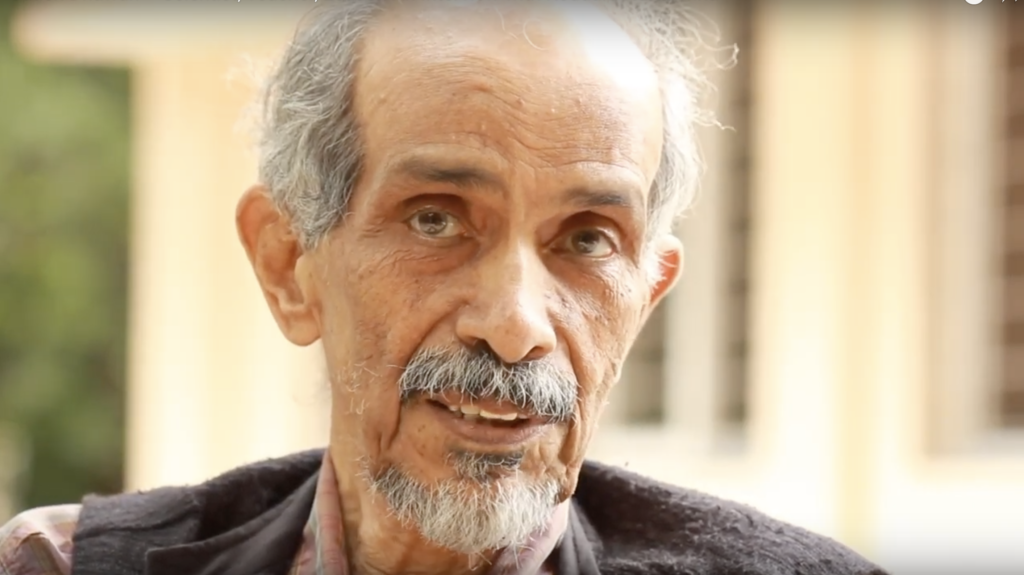

He was that kind of man: very tolerant and generous, very broad minded, very hard-working and very pleasant. I would say he was a charming person, a true scientist, a silent socialist, and a real patriot. \blacksquare

acknowledgement We thank the Office of Communications, IISc, for permission to publish this interview; Souvik Mandal for the audio and video recording of the interview and its editing; Megha Prakash and Rohini Krishnamurthy for help with the interview. We also thank Shilpa Gondhali of BITS Pilani, Goa, for help in transcribing the interview from the audio recording; and Jyotsna Dhawan for her inputs during the editing of this article.

Footnotes

- Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, now the Graduate Aerospace Laboratories of the California Institute of Technology. ↩

- He was referring to a house the family owned in Bengali Market, New Delhi. The house had been given to Dhawan’s father after Partition, to compensate for the one the family had to leave behind in Lahore when they moved across the newly created border. ↩