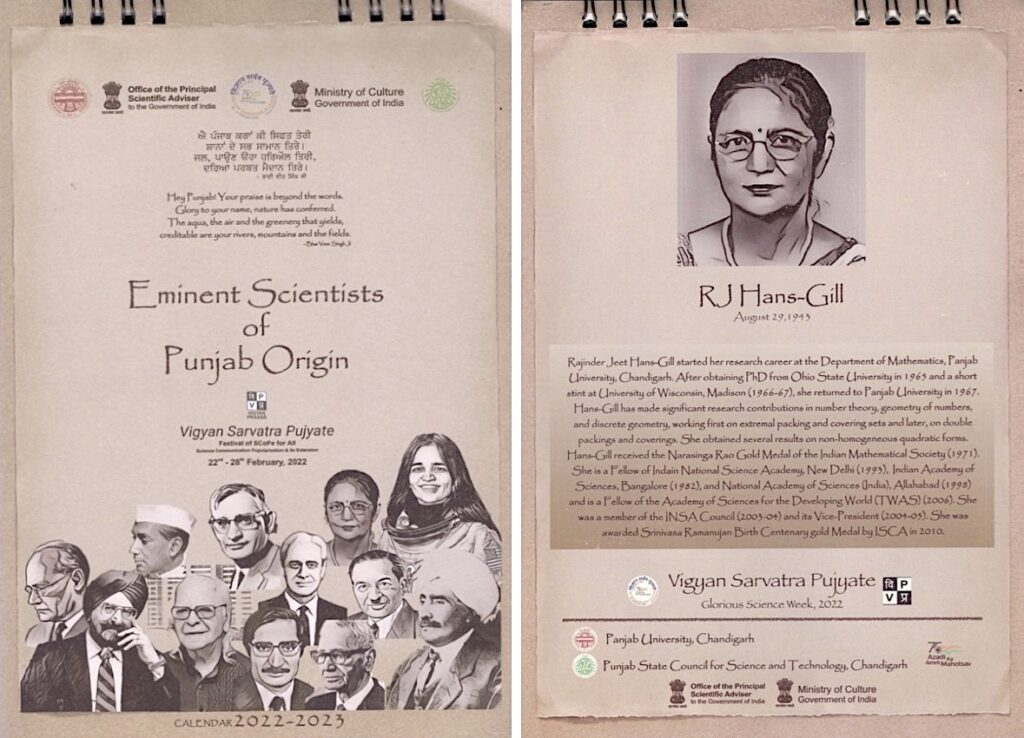

Watching her father work as a medical doctor in dispensaries, and her elder brothers going to school instilled a natural desire in her to study and to become a doctor. Nurtured by a supportive family, circumstances led her to pursue mathematics in college. Under the mentorship of the eminent mathematician Ram Prakash Bambah, she went on to obtain a PhD in 1965 from the Ohio State University, thus fulfilling her dream of becoming a doctor, of a different kind. Returning to India soon thereafter, she settled down to a life of dedicated research and teaching at the Panjab University, again supported by her family, especially her husband, Jagjit Singh Gill, who worked at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in Delhi.

With significant mathematical contributions to such topics as lattice packings and coverings, view-obstruction problems, conjectures of Watson, Minkowski and Woods in the geometry of numbers, she has won several laurels for her accomplishments, including the fellowship of TWAS (The World Academy of Sciences). Apart from co-authoring the book Lectures on Geometry of Numbers with Madhu Raka and Ranjeet Sehmi, she has co-edited, with Madhu Raka, the collected works of Hansraj Gupta in two volumes – a reverential tribute to her teacher and the first mathematics professor at Panjab University, Chandigarh – published by the Ramanujan Mathematical Society.

In a joyful conversation in the comfort of her home in Chandigarh, Rajinder Jeet Hans-Gill’s recollection is filled with her trademark laughter.

Thank you Ma’am for agreeing to be interviewed for Bhāvanā. You were born in Mohie, Ludhiana in 1943. Could you please tell us about your early childhood? Were you homeschooled?

RJH: I grew up in rural areas of Ludhiana district of Punjab.1 My father, Gursher Singh Hans, was a doctor. He was employed by the district board in Ludhiana district. There were five dispensaries at that time which were attached to this district. Doctors were usually transferred after five years. His first assignment was at Nurpur Bet. Nurpur was sort of a desert land. Sand everywhere outside as far as I could see. These days you don’t see it there. The only time I remember very distinctly is when we were going to our village home at Hans Kalan from Nurpur. We had to walk a long distance on foot first and then take a Tonga, you know a horse driven carriage. I couldn’t walk that initial stretch and I kept on telling my mom to pick me up and carry me. We had a person with us to help us and there was a donkey to carry some luggage. My brother was told to sit on it, but he was very scared and fell down when he rode it. I rode it for a little while, with my mom holding me. It feels like a strange thing now, that you go out and find only sand everywhere, walk a longish distance to a road from where you get a tonga. I seem to have enjoyed that ride immensely. But many years later when I sat in a tonga again, I found it very uncomfortable (laughter). Tonga is a hard vehicle to ride on, particularly sitting at the back. Perhaps it felt nice at that time because I was sitting on my mother’s lap.

Then I remember that my father got transferred to Kum Kalan and I have a lot of memories of that place. I must have been less than two years old when we went there. My brothers Lakhbir and Bhupinder started going to school there, and I just used to watch them. Bhupinder used a wooden Takhti (a small wooden board to write on). We call it “Fatti”. My parents brought one Fatti for me also as I too wanted to write like my brother. My mother would put some Gachni2 on it. He would write and I, like all children, wanted to do what the elder one did, trying my hand at writing.

The dispensaries at all these places where my father worked were small, and not big enough to be called hospitals. They were located away from the villages. There was accommodation for the doctor and the dispenser, just two quarters. Lakhbir was six years older to me, and he left after completing his schooling to study further, staying with relatives. The school at Kum Kalan was only up to 4th class. Bhupinder was two years older to me and he was going to school. I would write on the takhti and everybody would appreciate it. Soon I was reading second standard Urdu books and writing beautiful Urdu script. I was also learning addition and multiplication tables.

Was there a school for girls at Kum Kalan?

RJH: No. There was only a boys’ school up to 4th standard which was at quite a distance. One had to walk about a mile. Because I was keen to go to school, my father requested the headmaster for my admission, but he refused and suggested: “if she likes, she can come and sit with the students”.

I see, but not formally enrolled…

RJH: Yes, I could not be formally admitted. The dispenser’s son, who was called Chhota, was also of my age. He enjoyed doing arithmetic with me. Both of us would walk to the school together because it was far and I couldn’t go alone. At the school, we would just sit in the class and look around and hear what the teacher was saying. As far as I remember, we would sit in the 2nd class (laughter), though I am not sure about it now.

Like all children, I wanted to do what the elder one did

But I recall that two subjects which were taught were Urdu and arithmetic. One day it was announced that the inspection of the school would take place. The teacher told me and Chhota not to come on that day. But we were curious (laughs). So both of us went on that day and requested the teacher who said “Okay Baith jaao, baith jaao”. The inspector came and a question was put to the class. It turned out that the two of us were the first ones to answer it. Our answers were checked and were found to be correct. Then the inspector asked “What are your names?”, and started looking at the register (laughter). Not finding our names, we were told to go away (laughter). I don’t remember what the question was, perhaps something involving multiplication or division.

Did they allow you to come back later?

RJH: Not really. It seems the teacher, in whose class we sat, was taken to task by the headmaster. After that, I think I mostly stayed at home. I remember sitting at the school compound and watching students recite multiplication tables. I enjoyed that immensely. My father liked to teach me and so did my mother Gurdeep Kaur. She had continued her education after marriage, first privately and then through correspondence courses. They taught me at home. My paternal grandfather had this notion that arithmetic is the most important subject, that proficiency in this revealed how intelligent a person is. Over the years this encouraged me to do mathematics. I don’t remember any particular incident but in the later years he used to be quite happy with my answers to maths quizzes and would pat me. He used to call me “Vidya”, noticing my inclination towards learning at an early age. He didn’t live with us. He lived in our ancestral village Hans Kalan. But whenever he came he would engage us with his questions.

I remember sitting at the school compound and watching students recite multiplication tables

During your childhood you realized the lack of opportunities for girls, and you mention in an article3 that this made you think for long hours. Could you share your memories of that time?

RJH: Both my brothers went to stay with my uncle after passing their 4th standard. The only company I had was Chhota (laughs). We would play some games but he was very naughty. He would climb up to the roof that I couldn’t; so, as such, it was difficult to play together. It was a very lonely childhood that I had…. I had a lot of time to myself. I started noticing the domination of men over women and the privileges that boys got and the girls didn’t. I wondered why it was so. I observed that men earned money working outside their homes. They had the opportunity to go to school and get jobs; so it seemed to me that one must go to school and get a job. That seemed to be the only way to avoid male domination.

Your father would be very busy with his work, I imagine.

RJH: Yes, he went to the dispensary (which was just across our home) around 7 in the morning and came back in the afternoon. Then he had a little rest at home, read the news-paper and would go back in the evening for an hour or so. He did not interact with me as much as parents do these days.

Yes, usually that’s how the stories go. The youngest is cleverer whereas the elder ones are sincere and so on. Being the youngest one in your family must have made you very happy (laughs).

RJH: That’s right. Everyone was very kind and loving to me. My father always told my mother not to involve me in the household work. The result was that I never learnt any cooking (laughter), sewing or anything that the girls were normally put through in those days.

Could you tell us something about your earliest school years?

RJH: I was about six and a half years old when we moved to Isru. There was a primary school for girls in Isru. It was a school which was housed in a Dharamshala (a place like a community-centre) which had only one room in which all the five classes, from the 1st to the 5th, were held. At that time I was proficient in arithmetic and Punjabi. My father took me to that school and told the headmistress that since I knew these well (laughs) it would be very painful for me to be in a lower class; and I was admitted to the 5th class.

I didn’t enjoy this school at all. The atmosphere wasn’t stimulating. There was so much noise, with children running around here and there. The teacher took no interest in teaching. She sometimes talked about history in which I had no background. There were no books to read. I didn’t understand anything except arithmetic and Punjabi. In the final examination we were supposed to do some cooking and washing. My classmates were grown up girls and had no problem with these. The teacher was kind enough to just pass me in these subjects.

There was no girls’ school nearby, so I stayed at home for almost a year. During this time my father taught me English and geometry. The geometry book was in Punjabi. I had only one other book which was on English grammar. I had two cousins who would visit us. One was my maternal uncle’s son Karamjit who was studying at Dehradun. He spent summer holidays with us. He had some interesting books like Arabian Nights. He lent them to me and I read those stories over and over again. The other cousin was my Tayaji’s4 son Rajinder, a year younger to me. He came to stay with us because his father felt that he may learn more under my father’s supervision. Both of us became very good friends. The whole day I would tell him stories I had read (laughs) and he would listen.

When did your regular schooling start? Do you remember any teachers from that stage? Did you develop an interest in mathematics at that time?

RJH: When we moved to Isru, my brother Bhupinder had already passed the 4th class exam and won a scholarship. Since Isru did not have a high school, he joined a school in the nearby village, Nasrani. He found it difficult to walk to that school, so my father decided to send him to Garhshankar to stay with my uncle.

I too wanted to go to school and my father also felt that it was getting difficult for him to homeschool me. So, my father asked me whether I wanted to go and stay with my uncle for my studies. I said “yes”, since I wanted to go out and study like my big brothers (laughs). But my uncle refused. He was of the opinion that girls should not be educated. My uncle was the Naib Tehsildar.5 He had been transferred from Garshankar and was in charge of Balachaur Tehsil.6 There was a teacher from Isru who was teaching in a school at Garhshankar. He used to travel during vacations and my brother Bhupinder would accompany him. He had come for some work during the school year, I don’t remember the month. My cousin had stayed for almost a year with us, and my uncle had asked him to come back with the teacher. So my father told me: “Well, if you go there, it is very unlikely that he will refuse even though he has written in the letter, `ladkiyon ko nahi padhana chahiye’ (Girls shouldn’t be allowed to study); yet, if you go there I think he will agree. If you want, you can go.” I jumped at the opportunity. Both of us went with the teacher to Gharshankar about 15 kilometers from Balachaur. From there he put us on the bus to Balachaur. After we reached there, my uncle and aunt were shocked. My uncle asked me, “Why you have come?” I said, “I want to study”. He said, “Mainu kudiya nu nahi padhana” (I didn’t want to send girls to study). But I was there. After a couple of days he said, “Okay, I will find out if you can be admitted to the Arya school for boys”. My brother was studying there in the 7th class. I don’t know who made this suggestion, but my uncle told me later: “If you get dressed like a boy, you could go.”

I was very happy (laughter). My aunt was shocked but my uncle left her no choice. He gave strict instructions that I should henceforth be addressed and dressed as a boy. I was trained for tying a turban, and the very next day I went to school with my brother. I was provisionally admitted to the 7th class as my school leaving certificate was not there. Later it was obtained, with my name as Rajinder Jeet instead of Rajinder Jeet Kaur. The medium of instruction was Urdu, which I had forgotten to read and write; so I did not understand much of the teaching except drawing and English.

My school leaving certificate was obtained, with my name as Rajinder Jeet instead of Rajinder Jeet Kaur

Were the books in Punjabi?

RJH: The books were in Urdu. My brother would read them to me. I hadn’t learnt history before but I liked the history teacher very much because he would narrate it like a story that he had lived (laughs).

I never had such a teacher (laughter).

RJH: He would speak very nice Urdu. And of course, I could understand most of the spoken Urdu. There was also a prayer book in Sanskrit. We were told to learn at least ten shlokas (verses) from that book by heart.

Were your final years of schooling also in the same school? What were your grades like?

RJH: No, I spent about six months there. In the very first test I failed in mathematics (laughter). And the funny thing was that my brother got worried because my uncle was very strict. He thought if our uncle came to know about this, he would be very angry with me and I would cry. So he increased my marks, without my knowledge, in one or two questions before showing my answer book to my uncle. He was very kind to me! (laughs). So my uncle said: “Oh, you have done very well, you have passed the exam in mathematics.” And I was shocked (laughter).

Even in the history paper my brother saved me. The history teacher, who didn’t know Punjabi, had given me zero marks in some question, whereas I had written my answers in Punjabi. He had got it read by someone and found it incorrect. My brother spoke out the correct answers, pretending to be reading from my answer book, and got me passing marks. I did alright in English and science. There was no second exam as we had to leave the place before the annual exam because my uncle got transferred.

Just going to school was very satisfying for me, even though I had missed many normal activities of that age. It was fun at home since I got some privileges sporting as a boy, which my uncle’s two daughters did not have. Like my uncle had a mare for official purposes and I could take short rides on it with my cousin Rajinder. I found it very enjoyable. It was during this time that my uncle took me on a trip to an archaeological site with Bhupinder and Rajinder. I was also allowed to attend a religious congregation at Garhshankar, and to my utter disbelief the pathi asked me to sit in “tabia”7 of Guru Granth Sahib Ji. So that year, going around tying the turban proved very exciting to me.

My uncle got transferred to Hoshiarpur where I was admitted to a Khalsa school in 8th class. Even here, I spent only a few months and had to soon move out. But I enjoyed this school very much. It was much better than the previous one. It was nice and the teachers were really good. I somehow became a teachers’ pet and the other girls were very jealous of me.

That year, going around tying the turban proved very exciting to me

Was the Khalsa school open to both boys and girls?

RJH: It was co-education up to 5th class, and for girls only for higher classes.

Why did you leave this school and what was your experience in the new school?

RJH: My father got transferred to Gujjarwal where there was a girls’ school (District Board Girls’ School). But here I was utterly bored. The Khalsa school was very nice and I started missing it. There the teachers were nice, the teaching was better, and the general atmosphere was quite cheerful. But in this new school there was essentially no teaching in 8th class. There were no desks and one had to sit on the floor. But I suffered through it without any complaints since this was my only opportunity to get educated. In the 9th and 10th classes they did not teach mathematics as such. They only taught arithmetic as one subject and household as another. I wanted to be a doctor like my father. But there was no science teaching in this school. I was good at mathematics and wanted to learn more of it. So my father asked the headmistress if she could introduce the mathematics paper. But she was not in favour of it as she felt that maths was a difficult subject for girls. In the final exam of 9th class I got full marks in arithmetic and, in household I had very low marks. My father said: “You will not do household!” He advised me to learn some algebra and geometry during the summer vacation. Since my elder brother was in the same class, my father taught us from his books. We spent the whole summer doing geometry. Algebra was probably easier, but in geometry, you have constructions, propositions and so on. I found it very difficult initially. I am not sure if it is the same format now, that you have to write proofs in a particular order.

Yes. I think that’s still true.

RJH: And in the end, write QED. Right? (laughter). So that summer I spent learning mathematics of 9th standard and a bit of science also. After the summer vacations, my father contacted the headmaster in the boys school, and he said: “Well if you need a certificate for maths we will give it. But for science, there are practicals. You will have to send her for practicals.” These schools were at diametrically opposite ends of the village. My father was sort of doubtful. He didn’t want me to do medical because he thought it’s a very hard life for a doctor. Also I was rather young at that time. One had to be above 18 to be admitted to a medical college after the intermediate. He was of the opinion that I would have completed my MA by that time and be teaching already. It seemed logical, and we decided that I will take up maths in the 10th class. So for one year I studied maths at home. That is how I came to maths, and it worked out alright.

You also liked maths…

RJH: Yes, I liked Maths. I liked science too but I really didn’t get the opportunity to study it. I wanted to do something really practical which is useful to humanity, but somehow got into pure mathematics (laughter). For my higher education, I got admission in the Government College for Women at Ludhiana. I felt happy to join this good institution. At the time of admission I really didn’t know how to choose the subjects. So in the admission form, I filled in English, Mathematics, Economics and Philosophy as my choices. The board asked me to choose any one of Economics, Philosophy and History. I was not sure what to do; then one of the teachers suggested that I take Economics, as Mathematics and Economics were a good combination. When I came to BA, there was not much choice. I took the AB course8 along with a compulsory paper in English, and Punjabi as a subsidiary paper. I also took an Honours in Mathematics course.

You topped the class, right?

RJH: Yes, I topped in the university. I got full marks in the Mathematics AB course. And I stood second in the honours course. The university awarded me three medals at the convocation.

Great. So in those years what were your mathematical studies? Are there any favourite topics, favourite textbooks of that time that you remember?

RJH: I don’t quite remember the textbooks. I was much interested in calculus, algebra and geometry. I remember solving questions and discussing with my classmates in most free periods sitting on the floor in the corridors. Once a teacher asked “why are you sitting here like poor people”. I liked my maths teacher Miss Manchanda very much because she was an enthusiastic teacher. She contributed a lot towards my developing interest in mathematics.

The university awarded me three medals at the convocation

Where did you go for MA?

RJH: For MA, I joined the Government College Ludhiana, which also had co-education in some MA courses.

Did you face any difficulties as a woman?

RJH: Not really. I had got good marks in BA, and was very confident. When the news of the fact that I would be joining Government College Ludhiana reached the staff, most of them were happy to get a good student but there was one teacher, H.S. Sangha, who was very proud of his marks in MA, who apparently believed that girls are not capable of doing mathematics. I was worried a lot when I heard this because Sangha used to teach the course on Electricity and Magnetism in which I had no background. I looked at the book that was used for teaching and it seemed very difficult to me. But I was saved because my brother Lakhbir had taken the same maths course from Sangha two years earlier. He had meticulous notes. I started reading those and also looking at the book. When the classes began Sangha would try to show that I didn’t know anything. He would abruptly ask me questions which had not been done in the class earlier. He would call me by the marks I got in BA, and later by my roll number which was 40. Since I had already studied these topics I could always answer his questions. So surely he was very disappointed and I enjoyed that a lot. After a few months, he became friendly and stopped asking me abrupt questions. Apart from that, my experience with other teachers and classmates was very good. The male classmates were always polite to the girls. The other teachers were very encouraging, particularly professors K.R. Chaudhary, Manohar Singh, Bhagat Singh, B.S. Lali and O.P. Bagai. My brother Lakhbir had saved me from what could have been very problematic for me. I gained immensely by discussing with him throughout my MA studies and I am very grateful to him.

When did you meet Professor Bambah for the first time?

RJH: My first interaction with Dr. Bambah started like this. The teacher who had been assigned the teaching of Algebra course to us was teaching it for the first time. He used the textbook Modern Abstract Algebra by Shanti Narayan. I used to try questions from other books also. There were some questions which I could not solve and for which my teacher could not help. I discussed this problem with Professor K.R. Chaudhary who was the head of the department and who used to visit the mathematics department in Chandigarh for some meetings. He offered to talk to Dr. Bambah about this. Dr. Bambah said that he can help me if I can come to Chandigarh, so an appointment was fixed. I came to Chandigarh and stayed with a relative who lived on the campus. Dr. Bambah said “I have time only in the evening”. So I went to his house in the evening with my books and questions. He helped me solve some questions, and for some others he said he will think about and let me know. It was a very nice meeting. Maybe after two or three weeks, I went to meet him again and he explained the remaining questions.

The next time I met Dr. Bambah was when I went for a job interview after appearing for the second year MA examination. There was an advertisement for assistant lecturers in mathematics at Kurukshetra University. During the previous couple of years, students who stood first in MA mathematics at Panjab University had joined this post but had left after a year for one reason or the other. For instance, Professor I.B.S. Passi went to UK for research. His successor J.D. Gupta qualified for the IAS examination and left. So it seemed like Kurukshetra University was a good place to go to and transit from there to further one’s career (laughter). I hadn’t thought that I would come here (Panjab University) to do research at that time.

Professor Chaudhary was very keen that I take the IAS exam. He would say, “At least show us by getting selected once to IAS” (laughs). To this I said, “What is there to show? I would lose one or two years doing that.” My parents left me free to make the choice. I had thought that I would take up a teaching position for one or two years and then go abroad to study. So, I went for the interview. Dr. Bambah was there! Of course, I knew him before. Professor Shanti Narayan was there too, but I hadn’t known him before that. He was chairing the interview committee. As I entered the room, Dr. Bambah immediately asked me: “Why have you come for this interview?” I was so shocked (laughter). I said that I wanted to teach. “You should go for research. Why do you want to teach?” he asked. I replied that I wanted to spend one or two years teaching, gain some experience and then go abroad for research. He said, “No. You will waste your time.” I said that I had been taught for so many years and now I wanted to teach.

Did this conversation happen during the interview?

RJH: Yes, I was getting convinced about research but I didn’t of course say that. Dr. Bambah said that if I came to Chandigarh, they would try to get me a scholarship, but I kept insisting that I wanted to teach for some time and then think about research. Eventually I did get that job (laughter).

Later Dr. Bambah sent me a message through Dr. O.P. Bagai who said: “Look, he is such an eminent mathematician with vast research experience and he has asked me to talk to you about doing research at Chandigarh. You should consider it favourably.” Professor Bagai had been my teacher at Ludhiana. He had somehow got the impression that I came from a poor family. So Dr. Bambah had offered that if I joined the research immediately then he would try to get me some monetary help until the university scholarship was made available. I told him that I had no monetary problem and agreed to join the research after the declaration of result. But I was told that I should join as soon as possible and not wait for the declaration of the results.

My parents left me free to make the choice

I was offered a junior research assistantship which had a teaching component also. When I came to Chandigarh I found it quite stressful. It was a new environment and the work was very heavy. Dr. Bambah had advised me to repeat some parts of analysis and algebra courses that I hadn’t learnt them well enough, even though I had got good marks in these papers. So I was attending these MA classes. Also there were some seminars for research students in the afternoon. I told Dr. Bambah that I did not want to assist in teaching and only wanted to do research. He said then I would get less money. I accepted it and was later offered a scholarship of lesser value.

I hadn’t thought that I would come to Panjab University to do research

There was a nice program chalked out for us, namely research seminars which were held in the afternoon in the hot weather. These were attended by all research scholars and most of the faculty members. The program would typically start at 2 pm, and go on until 5 pm with a tea break in between.

Dr. Bambah was very strict. One had to be in the class on time. Once it so happened that Harsh Anand, who was my batchmate and who shared a room with me in the hostel, got delayed for some reason. I think we were double riding on my bicycle, probably because her bicycle was punctured. When we reached the seminar room we were half an hour late. We saw Professor Rajinder Singh. He was a statistician. He said, “Go upstairs, and face the music”, showing the way towards Dr. Bambah’s office. Dr. Bambah looked very angry but didn’t say very much. Whatever he said was meaningful. He said, “Do you realize how much time you have wasted? A total of 10 hours, one hour each of each of us here.” and asked me what had happened. We told him about the bicycle puncture. But his words stuck in my mind and I always tried to be very punctual. We never arrived late again for the seminars!

Were you formally enrolled for a PhD?

RJH: No. I wasn’t. You first joined as a student and would register for PhD after you got some results.

Were there batchmates at that time who became your colleagues or collaborators later?

RJH: There was Vishwa Chander Dumir. He had done his MA from Panjab University Campus in the same year in which I completed my MA. He had topped the class. After some initial hesitation we started communicating with each other about our studies. We enjoyed working together and later wrote several joint papers.

Could you share something about other research scholars in the department at that time?

RJH: As I mentioned before, there was Harsh Anand who did her MA from Patiala. There were two senior research students, Satish Kumar Aggarwal and Gurnam Kaur, who were already working with Dr. Bambah. Later Dr. Bambah selected me and Dumir to work with him. Harsh Anand started working with Professor Hansraj Gupta but later went to the US for her PhD.

Satish, Vishwa and I went to Ohio State University (OSU) along with Dr. Bambah when he moved there and completed our PhD there. Gurnam Kaur could not accompany us. She had got married and her husband did not allow her to go abroad. So she got her degree from Panjab University. She was the first woman to receive a PhD in mathematics from this University.

There were a couple of other research students as well but I don’t recall much about them.

When you moved to OSU as a research student, it may have been an unconventional move for a woman in India those days. And it was also your first time travelling outside India. Did you travel alone or were you with other students of the group?

RJH: At that time, I was quite involved with mathematics. I knew several people who had gone abroad and got their PhDs, so I didn’t feel any uncertainty or had any difficulty going there. Only that some relatives asked my mother as to why she is sending her daughter abroad before marriage and so on. My parents were not influenced. They had complete trust in my abilities and choices. I also had no apprehensions at that time. It felt nice and I was happy (laughs).

So your parents were supportive.

RJH: They were completely supportive. Never even once did they say anything otherwise. The fact that I was going with Dr. Bambah, his family and my colleagues left them with no worries. As I mentioned before, Gurnam dropped out at the last moment but otherwise she too was preparing to go along. In fact, the three of them had gone to Delhi to get their certificates for waiver of police verification when I had gone home for the summer vacations. The procedure to get passports issued at that time was different. If one applied without that certificate, it took longer, like six months or so. But Dr. Bambah had given them a reference to an ICS officer in Delhi (actually the father of my future colleague in the department, A.R. Rajwade. At that time of course we did not know Rajwade). If one got his recommendation, the process would not take more than a month. So, all three of them had gone together to get the certificate. When I returned from the vacation, Dr. Bambah told me that I could follow the same procedure and apply. But I had to first go to Delhi for that. I had been to Delhi only once before, accompanied by my brother. I was hesitant to go alone. This time Vishwa was kind enough to accompany me. Soon, all four of us had our passports ready.

Since all of you had probably done work enough for a PhD, it seems like it did not take too long before you obtained your PhD degrees from OSU because you got your degrees in 1965 itself. Also, I think you were the youngest, right?

RJH: Yes, youngest at that time at OSU. I didn’t think much about it but Dr. Bambah would sometimes mention it proudly.

How long did you stay in the US beyond your PhD and what was your experience? Any conferences, seminars, or people you met that you remember making an impact on you?

RJH: During my stay at OSU, I had the good fortune to meet many eminent mathematicians. The first was Professor Hans Zassenhaus. I had studied Zassenhaus lemma in the algebra course and had held him in awe. At that time I had not imagined that I would ever meet him. Whenever we met he would say Hans meets Hans. He organized a computational number theory seminar in the department, which was very interesting.

Another was Professor A.C. Woods who worked in geometry of numbers. I later had a joint paper with him and Dumir during my next visit to OSU. Both Professor Zassenhaus and Professor Woods were examiners for my PhD thesis.

I also had an opportunity to interact with the Hungarian mathematician László Fejes Tóth and A. Heppes. I remember that there was a number theory conference where I met H.B. Mann. I had very good interactions with him later when I was in Madison.

Whenever Hans Zassenhaus and I met, he would say Hans meets Hans

I stayed at OSU for one quarter after getting my PhD. Thereafter, I applied to some universities and got offers from three places. I chose University of Wisconsin, Madison because Professor Michael Bleicher, who also worked in the same field, was there. Of course, Professor Mann whom I had met at the conference was there too. Dumir and Satish Aggarwal both went to University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. I completed almost one year in Madison and came back to India on one year leave. The appointment there was initially for three years with the possibility of extension. I had thought that I would return after the leave, but I didn’t go back (laughs).

I think Dumir spent two years in Illinois and came back to Chandigarh in 1968. Dr. Bambah also came back around that time. Satish Aggarwal came back after several years and joined Maharshi Dayanand University at Rohtak.

You came back in 1967 and joined the mathematics department of Panjab University.

RJH: Yes. I had an offer from the Tata Institute (TIFR) as well. But then I had been away from home for almost three years and I wanted to be near my family. Had I opted for the Tata Institute, I could visit my parents only for a few days; that was the reason I selected this place. I have often felt later that I should have gone to TIFR. Had I gone there, I would have learnt more mathematics because that offer was a research position. Also TIFR being a research centre had an active research program. But that’s how life is. One doesn’t know!

When you joined the mathematics department at Panjab University, it was a thriving department, I believe, built with a lot of love and efforts by professors Hansraj Gupta and Bambah. Could you please tell us about the department as it was when you joined and how it has evolved over the years?

RJH: When I joined here in 1962 as a research student the department was quite active. In 1963 it was recognized as the Centre for Advanced Studies by the UGC due to the efforts of Dr. Bambah. Professor Hansraj Gupta was the Head of the Department but he was on leave visiting the US for most of that year. When he came back he gave us a course on partition theory and we also had the experience of his unique method of teaching. We had algebraist Professor I.S. Luthar and Dr. Sudarshan Sehgal. There were several seminars going on during my stay here. Dr. M.L. Madan gave a seminar on algebraic number theory and Dr. Rajinder Singh gave lectures on measure theory. Professor Bambah introduced us to geometry of numbers in his extensive seminars. T.P. Srinivasan and Dr. N. Sankaran were also active participants in the seminars. In fact, a suggestion of Srinivasan while I was talking about my research work in a seminar helped me to obtain alternate proofs of my results. My senior Satish Aggarwal also gave a seminar on diophantine approximations.

There were some foreign visitors also. In particular W.J. Thron visited the department for a few months and lectured to the research students when he was preparing his manuscript on topology.

But in 1964-1965 several faculty members and research students left for foreign universities. Professor Hansraj Gupta retired in 1966. So the department had lost its strength. Dr. Bambah came back in 1968 and started expanding the faculty. In a couple of years we got good faculty strength and an active visitors program.

How has the department evolved over the years?

RJH: The department had a strong group in pure mathematics that included Dr. I.S. Luthar, Dr. V.C. Dumir, Dr. A.R. Rajvade, Dr. V.C. Nanda, Dr. Sundar Lal, Dr. H.L. Vasudeva, Dr. N. Sankaran, Dr. Satish Shirali, Dr. I.B.S Passi, Dr. R.N. Gupta and Dr. K.S. Sarkaria. And we had applied mathematicians Professor S.K. Trehan and Professor S.K. Malik. Professor Manohar Singh spent a couple of years here and went back to Simon Fraser University. The department made considerable progress in matters of research and teaching. The university had started an honours school in science departments and the responsibilities of the department increased manifold. There was a lot of subsidiary teaching apart from the BSc (Hons.), MSc (Hons.) and MSc classes of Mathematics (the nomenclature of MA Mathematics had been changed to MSc. Mathematics in the meanwhile). The responsibility of the College Science Improvement Programme (COSIP) for improvement of teaching in colleges was taken up by the department. Several books were written for college teaching. I wrote one on geometry, jointly with Dr. Bambah. The faculty devoted considerable time to this program. As a result of all this, and the expanded teaching load, the vision of Dr. Bambah that the faculty should have more time for research and be able to visit other institutes for research was affected. Still, the department faculty continued to organize some seminars, conferences, ATM (Advanced Training in Mathematics) Schools and Faculty Enrichment Programs. The faculty members continued to attend conferences and visited other universities for research. Most of us started guiding research students, and in due course the department had a good PhD programme.

You must have been to some international conferences. Tell us something about the resulting interactions.

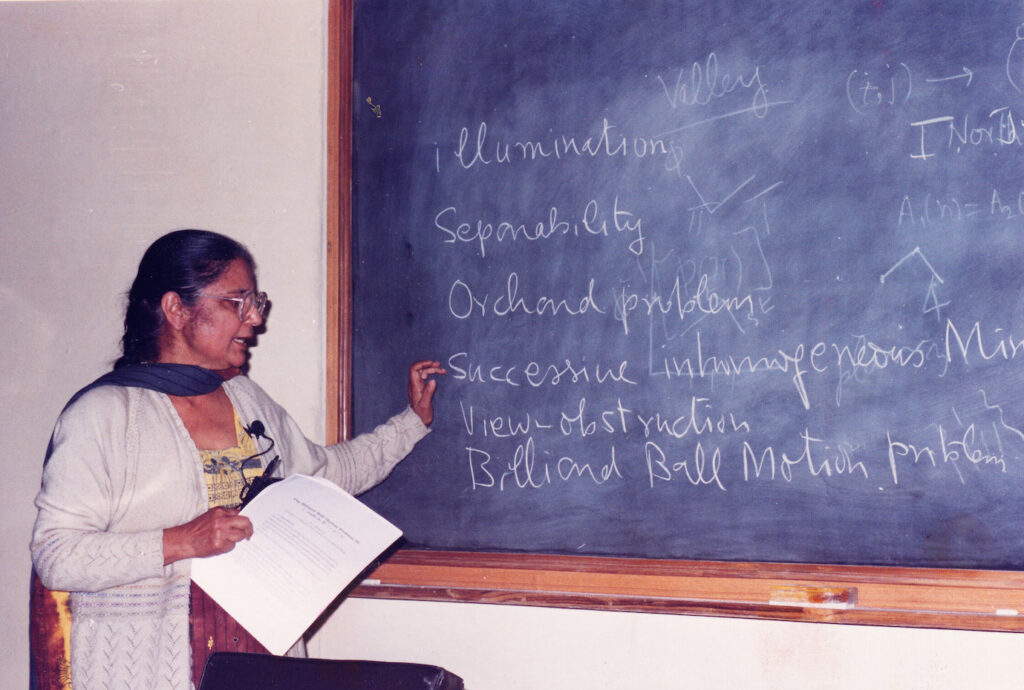

RJH: Yes, I had the opportunity to attend several national and international conferences and I also went on short visits to other universities. In particular I attended Discrete Geometry conferences at Oberwolfach in Germany. There I met several mathematicians including P.M. Gruber, L. Danzer and J.B. Wilker. These mathematicians later visited our department a few times. Wilker, Dumir and I collaborated and wrote several papers together on the view-obstruction problem.

I don’t remember but Professor Wilker reminded me that I had asked him to come to Chandigarh sometime when we met at a week long conference at Oberwolfach. I must have said that, but I had not expected that he would land here one day without any prior information. I was the department chairperson at that time, and sitting in my office I got a phone call that he is in Chandigarh with his family. I was so shocked. Later I asked him as to why he didn’t inform us beforehand. He said that he had written a letter to me but then could not wait for the reply. I hadn’t yet received that letter then. He was on sabbatical leave and had come with his family but had not made any arrangement for their stay in Chandigarh.

Could you make the arrangements?

RJH: Yes, we could. They stayed in the university guest house for a few days and then in one of the flats for the visitors.

We are all aware of the difficulties in navigating the academic and administrative challenges of the university that come with a lot of responsibilities and limited resources. How did you balance your research, teaching and administrative duties through the years?

RJH: I was very conscious of the fact that one should not let domestic issues affect the department work. If a woman is lax about her job it is noticed more. It seemed to me that it is the reputation of women that is at stake, so I tried to take up these responsibilities very seriously. My husband was very supportive and always encouraged me to attend to my official duties on priority.

When did you start supervising PhD students?

RJH: I had started guiding one student in 1972. She was a bright student but left after a few months to take up a teaching job. So did some other students who were working with other faculty members as well. At that time research fellows were paid very less and students opted for teaching jobs. Later in 1975 Madhu Raka started working with me and got her PhD in 1979. She is my only PhD student. Around that time very few students opted for research. Most of my colleagues got only one or two research students except the applied mathematicians. In later years PhD in mathematics became more popular and my younger colleagues got more students. At that time I was very busy in research, teaching and administrative responsibilities and didn’t see any advantages of getting research students. But now I think I should have guided some more.

But at that time perhaps you felt that a student’s interest should come naturally…

RJH: Yes. It must come naturally and should be a voluntary pursuit. The only other student whom I wanted to guide was Ranjeet Sehmi (who co-authored papers and a book with me later). I had taught her and she was very good. When she finished her post-graduation she wanted to take up a job. She said she needed a job. Research scholarship was very little at that time also. She got a job in the Punjab Engineering College. When she wanted to do a PhD later I was not free. My mother was very unwell and so she worked with Professor Dumir.

Would you like to tell us about the journey of proving Watson’s conjecture on the non-homogeneous minima of quadratic forms? And how did it come about?

RJH: I was introduced to Watson’s Conjecture by Dr. Bambah in his lectures on geometry of numbers when I was a research student. In his lectures he proved a theorem of Minkowski (1901) on the non-homogeneous minimum of product of two linear forms in two variables. This can be interpreted as a result on indefinite binary quadratic forms. Its extensions to n variables had been studied by various mathematicians. In 1948, Davenport had obtained the result for n = 3. Birch had obtained it for forms of signature 0 and for all n. In 1960, G.L. Watson obtained it for special types of forms in n variables. In 1962, he obtained the results for all n \geq 21 and conjectured the exact values for all n \geq 4. These depend upon congruence classes of absolute value of signature \sigma modulo 8. The problem for small values of n was considered difficult. Dr. Bambah suggested to V.C. Dumir to work on this problem for n = 4. He promptly solved the two cases |\sigma| = 0, 2 and this was a part of his PhD thesis. When Madhu Raka started working with me in 1974, Dr. Bambah suggested that she may work on the n = 5 case. She obtained these results under my guidance and published them in 1980. Following the method of Birch, Raka proved Watson’s conjecture for all non-zero signatures between - 3 and 4. This was part of her post-doctoral work. Using the results of Dumir, Woods and myself (1994), the proof of Watson’s conjecture was completed.

In fact, working on these ideas I believe, isn’t there a conjecture that bears your name with your collaborators?

RJH: Since indefinite quadratic forms take both positive and negative values, one can consider one-sided inequalities as well. The minima of positive values of non-homogeneous indefinite quadratic forms was obtained for certain small values of n by Davenport and Heilbronn, Blaney and Barnes. Dumir obtained two cases for n = 4 and these are part of his thesis. The third case of signature -2 was obtained by Dumir and myself in 1981. Raka had already obtained the result for \sigma = 1, 3 and n = 5 under my guidance. So the n = 5 case was complete except for signatures -1 and -3. The case \sigma = -1 was settled by Bambah, Dumir and myself. In fact, we also determined the second minimum in this case. In a series of papers during 1981 to 1984 we proved it for all signatures between -1 and 3. Then we made a conjecture for all n \geq 6 and all signatures. In the literature it is known as Bambah, Dumir and Hans-Gill conjecture. It is now completely settled. For n = 5 and signature -3, the exact value is still not determined in spite of efforts of Dumir and Sehmi (1994), Raka and Rani (1997), Bhardwaj and Raka (2023).

Coming to your further collaborations within the department and outside, what were the other themes that have picked your interest?

RJH: Minkowski’s Theorem (1901) can also be generalized to results on the product of n non-homogeneous linear forms. In fact, Minkowski is believed to have conjectured this generalization. A large number of mathematicians have worked on it. Madhu Raka, Ranjeet Sehmi and myself could prove a related conjecture of Woods for n = 7 and 8 in the years 2009 and 2011 respectively, and thereby completed the proof of Minkowski’s conjecture for these dimensions. It is gratifying to me that work in this direction is further continued by Madhu Raka and her student Leetika Kathuria, who have proved it for n = 9 and 10.

Dumir, Wilker and I developed a fruitful collaboration

In addition to working on the conjectures of Minkowski, Woods and Watson, I have also been interested in view-obstruction problems. As I mentioned earlier, Dumir, Wilker and I developed a fruitful collaboration on this theme when Wilker visited Chandigarh. This problem was initially formulated by J.M. Wills (1968), and was later interpreted geometrically by T.W. Cusick in 1973. It involves considering the set of points with positive integer coordinates and a certain centrally symmetric convex body such as a cube or a ball in the Euclidean space. The translates of this convex body are placed, centred at these integral points. The problem is about finding the smallest expansion of the convex body so as to block all rays from the origin into the open positive cone. We worked on certain extensions of this problem, and in 1991, myself and Dumir obtained Markoff chain type theorems for 2 and 3-dimensional cubes. We also obtained similar results for spheres. When L. Danzer visited us in 1986, he became interested in this problem and found some counter-example. Dumir, Wilker and myself developed a general theory of view-obstruction problems and also worked on the conjectures of Schoenberg. View-obstruction problem for boxes was later known as “lonely runner conjecture” in literature.

In my PhD thesis, I had worked on maximal and minimal sets for coverings in certain classes of sets. I also obtained the covering constants of several non-convex symmetrical domains and determined all maximal covering lattices of these domains. An important problem in the geometry of numbers is to find methods for determining the critical determinant of a given set. Reinhardt and Mahler had independently proved that a convex domain in the plane can be inscribed in a space filling convex domain with the same centre, which has the same critical determinant. I showed that this result does not generalize to higher dimensions.

It was known that the general covering density of a symmetrical convex domain is equal to its lattice covering density. Bambah, Dumir and myself (1977) showed that this result does not extend to symmetrical star domains. This was our first joint paper with Dr. Bambah.

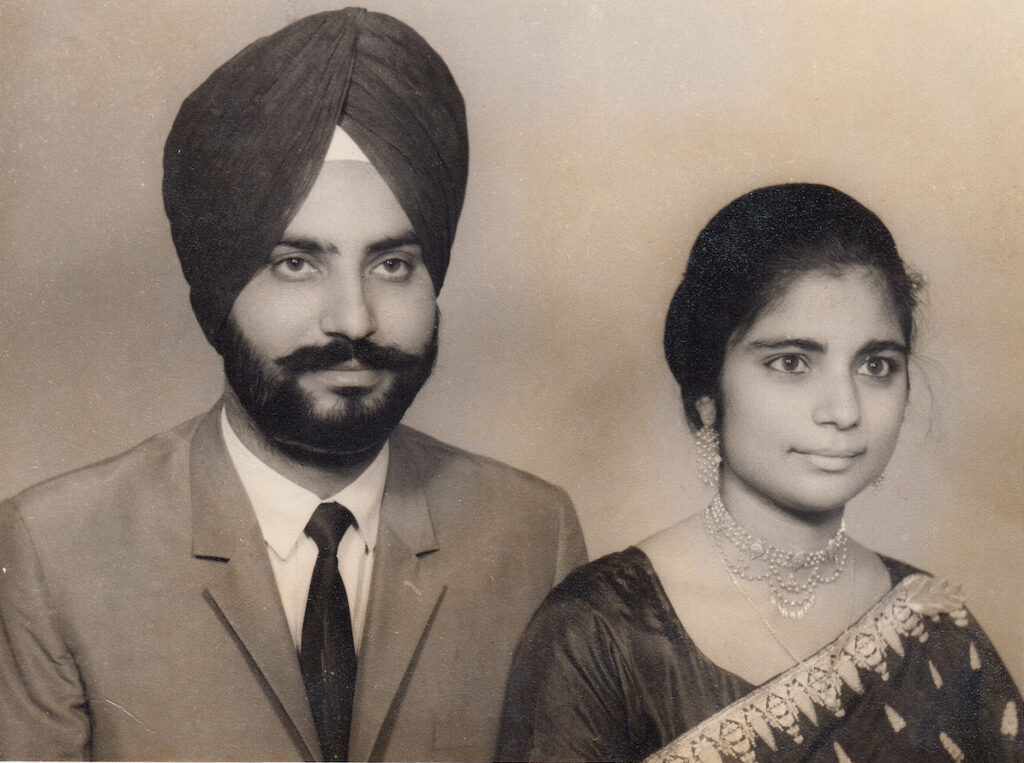

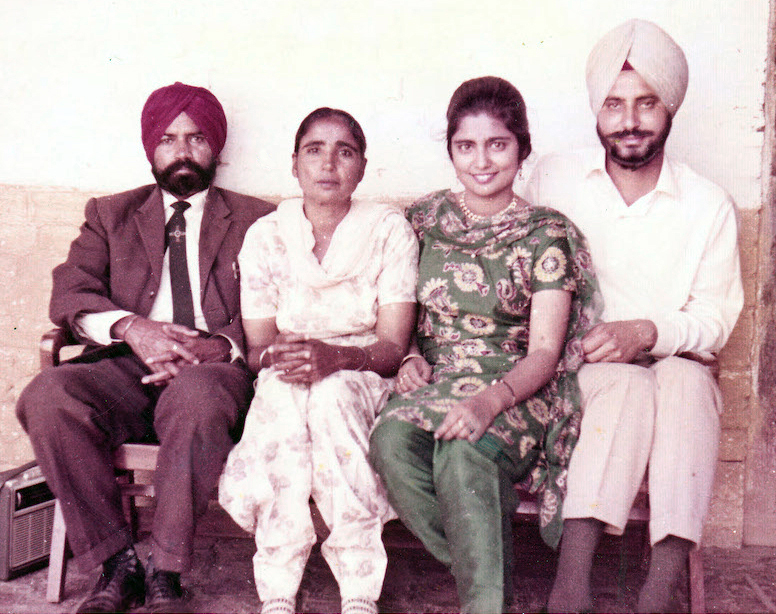

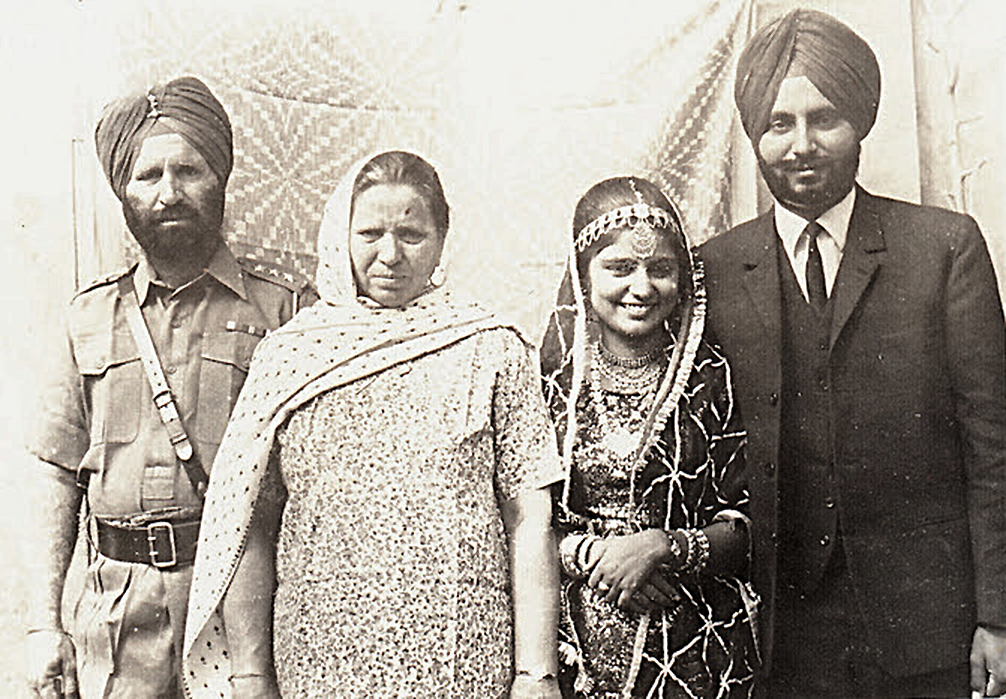

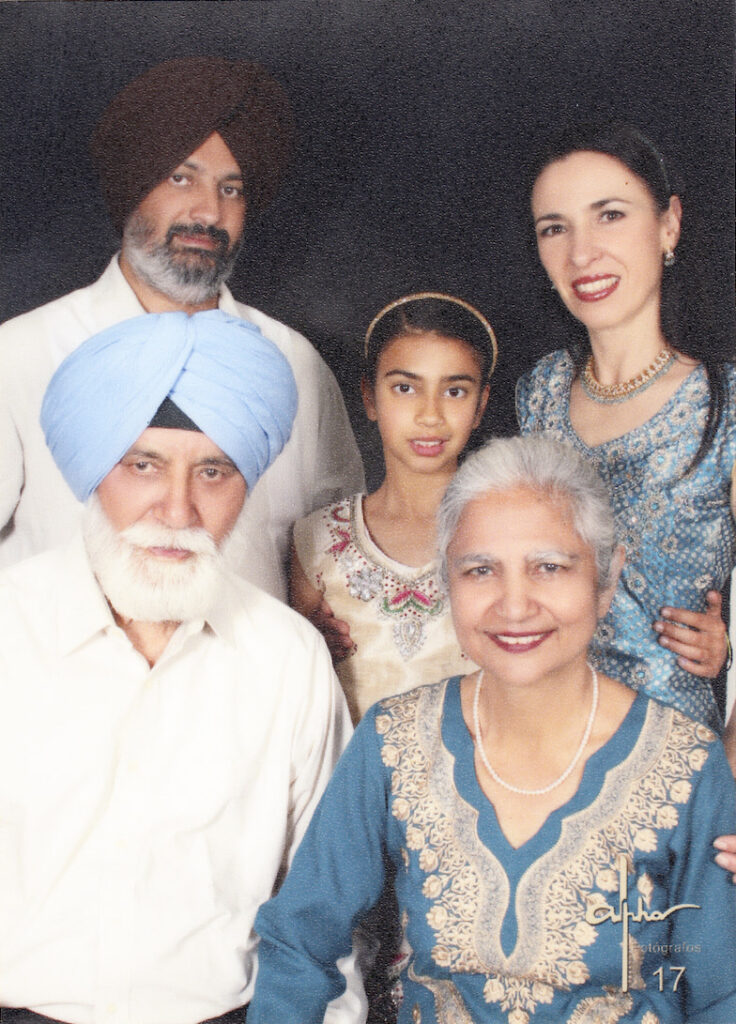

Fascinating. We have seen that you co-edited a book on number theory, and have also authored a book on the geometry of numbers with your younger colleagues Madhu Raka and Ranjeet Sehmi. Let us now turn to your family life. You married Professor Jagjit Singh Gill in 1968. Would you like to tell us how and when you met him?

RJH: It was an arranged marriage. My parents had an advertisement in the newspaper and he had responded. Later it came out that my brother Bhupinder and Jagjit had some common friends. So Bhupinder played a big role in our meeting. We met at Bhupinder’s house in Delhi. Of course I liked Jagjit because he was very handsome. The main quality that I admired in him was that he was helping his father, along with his research job in the nematology division at IARI (Indian Agricultural Research Institute). His father had retired from a military job and he had taken up farming in his land. It was the summer of 1968, when the wheat was being harvested. He had gone from Delhi to his village to help his father and he came back to just meet me. I appreciated that. He was so kind to his parents, and so helpful. And that has been his quality throughout. He has been very helpful to his parents and to his grandmother. You think that is a good quality, but there is nothing absolutely good in this world. I mean that he had to spend so much time with his parents, so much attachment he had. They expected he would visit them very frequently. At first he would go after every two weeks. Then, maybe once a month he would go there. And there were other things to attend to. One doesn’t really know what is good for you, and what is bad.

He was working for the IARI in Delhi and you were at Panjab University. How did you balance the mathematical life, family life and also his responsibilities towards his family?

RJH: Somehow it worked out. In the beginning, we would meet on most weekends. Either he would come to Chandigarh or I would go to Delhi. There were also some holidays to look forward to. Later when children were born I stopped going and he would come almost every weekend. Then he accepted an appointment at Central Potato Research Institute in Shimla, hoping that Shimla being nearer, it would be easier to travel. But then it took the same amount of time, which didn’t work any better than Delhi.

So he was in Shimla for a few years?

RJH: Yes, but later for some professional reasons he went back to Delhi.

It’s famously known as the 2-body problem. Husband and wife both working, and living in different cities. When your children were small, did you have your parents or mother specially supporting you?

RJH: Yes, My mother helped me a lot when my children were small. My mother-in-law also helped. Again that is positive, as well as negative (laughs). My daughter, Ramneek, who is the elder one, stayed with me for six months after she was born and then I left her with my mother-in-law. She stayed with her for two and half years, and when she was about three years old, I brought her and put her in a nursery school here. I had thought I would bring up my second child myself, but when my son Hardeepak was a few months old I had to leave him with my mother because both of us got whooping cough. Later both children came to Chandigarh and stayed with me.

When did you retire from the university?

RJH: I retired in 2005 at the age of 62.

Did you continue teaching or your research collaborations after retirement?

RJH: I did not do any teaching after my retirement. I was first appointed an NBHM visiting Professor and then I had an INSA fellowship for five years so I continued doing research work. Unfortunately my colleague and collaborator V.C. Dumir passed away in 2006. I continued my collaboration with Madhu Raka and also with Ranjeet Sehmi.

There are a few general questions. From a predominantly university system in the Indian academic scene around the time you were growing up, higher education appears to have become institute centric during the past few decades. So, we would like to hear your reflections on this especially since Panjab University has been one of the few places in India where the university culture thrived better.

RJH: In my opinion university culture is better. Institute-centric may be better for some people who are more focused and really dedicated. For them, it’s good but for people with wide-ranging interests, the university atmosphere helps provide an exposure to other activities, I think. I don’t particularly like the institute culture which tends to be very limited in its reach.

What are your thoughts on changes in mathematical education over the years? Especially integrating with technology in recent years?

RJH: It is true that things have changed much over the years. Since I have not been teaching for the last several years, I am not aware of how much technology is being used in classroom teaching. As far as I know the syllabi are almost the same as before and it depends upon the teacher to use the technology to introduce new methods of teaching. There are vast possibilities of use of technology in teaching. But I have no idea how much it is being used. Presentations in the seminars and conferences have definitely become more interactive. But it has a negative side also. In the seminars delivered with powerpoint, the presentation usually goes very fast. One enjoys the beautiful slides but later finds that much has not been retained. Of course one can supplement by taking photos of slides and looking for references on the internet. But I feel that the pleasure and satisfaction of attending a chalk-and-board lecture is lost. It is possible to attend meetings and conferences virtually. The availability of the material for teaching and research on the internet is a boon. It is useful for both teachers and students.

Coming to the final two questions, you have built an immensely productive mathematical life passing through several challenging phases in the history of our country, the development of a scientific ecosystem in India and of course your personal challenges including additional ones that are faced by women. Would you like to share a message for young mathematicians who face their own adversities and challenges?

RJH: What I feel is that generally one has to make a decision at some stage about what one wants to do. There are so many directions these days, you may become an engineer, computer engineer, artificial intelligence expert or a doctor. There are so many attractions and the parents may also be putting some pressure. Just for an intelligent person to say, “I will do Mathematics” is not that easy. Right? That is what happened with my niece’s son. His parents and grandparents tried a lot to convince him to go for engineering. Whereas he wanted to do physics, and later he switched to applied mathematics. That way one has to decide and be firm about it. You will see that these jobs may not be all that lucrative and at times it could be very depressing, particularly in research when you are not succeeding. It’s very difficult but one has to keep at it once you have made a decision, and an academic life is not entirely bad I think (laughs). There are more opportunities now than before; I mean more professions to choose from. Maybe there is more competition also but the joy of research, you know, and solving a problem is unmatchable. Right? So one has to work for that. Main thing is that once you have decided what you want to do, you should just do it.

Whatever your heart says.

RJH: Yes. There are many options, but one has to work day and night. It’s not that success in mathematics comes easily. Particularly for me, working in the university was really an advantage. Then I could work at home in my free time. This also had a little disadvantage. My children said, “You have to work too much as a teacher in mathematics because you are working at home too.”

Yes, your mind does not stop working…

RJH: That is how it is. My mother once said “Ke mainu te pata hi nahi si ke inna matha marna payega tenu PhD kar ke ve. Professor lag ke vi padna khatam nahi hoya” (I never knew that it would be so hard for you even after PhD. You have not finished studying even after becoming a university professor).

I believe many people do not understand what a life in mathematics research is about.

RJH: Yes, they cannot understand that when one is working on a problem he/she is totally absorbed in that.

My husband often wondered why in some general get-togethers in the department in which spouses were also present, we would start discussing mathematical problems. My family could not understand that my main occupation involved both teaching and research.

That’s true. It was a fascinating conversation Ma’am. Thanks a lot for making this interview possible and answering our questions joyously.

RJH: Thank you.

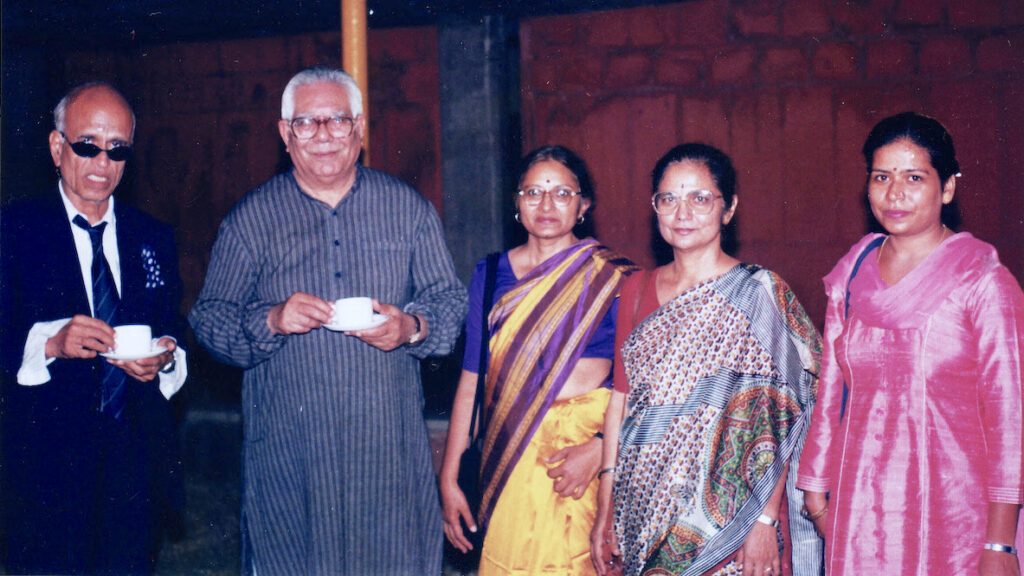

acknowledgements It is with great pleasure and warmth that we would like to record the immense help received from Gurmeet K. Bakshi, Madhu Raka and Dinesh Khurana at every stage of preparation of this interview right from arranging, coordinating and editing. We are grateful to Shilpa Gondhali for her ever willing help with timely transcribing of the audio recordings. The final editing of this article would not have been possible without Keerti Vardhan Madahar’s crucial help, sitting with Professor Hans-Gill over several sessions and coordinating with her, and we are deeply indebted to him for his warmth and kindness. We are very grateful to C.S. Lakshmi of SPARROW (Sound & Picture Archives for Research on Women), Mumbai, for her kind and warm disposition to readily share high-resolution copies of three photos from their collection that are reproduced in this article.\blacksquare

Footnotes

- Before the partition of India it was spelt as Panjab, now it is generally spelt as Punjab. The word ‘Panj’ means ‘five’, and the word ‘ab’ means ‘water’ referring to the five rivers of the Panjab region. ↩

- A type of (Multani) clay, which is used to coat a wooden board for writing or practicing calligraphy. ↩

- See the article titled “In search of equality” in the book Lilavati’s Daughters, published by the Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore. ↩

- Father’s elder brother. ↩

- The term `Naib’ refers to `deputy’ highlighting the role of the Naib-Tahsildar as the second-in-command in the Tehsildar’s office. ↩

- Tehsil is an area of governance including a town and villages around that town. ↩

- Pathi is an official in gurudwara appointed to read Gurbani on regular basis and perform other related duties. Tabia is the unique seat (often on a raised platform) to read Gurbani. ↩

- AB course in mathematics (in Bachelor’s degree) at that time meant that there were two subjects in mathematics. ↩