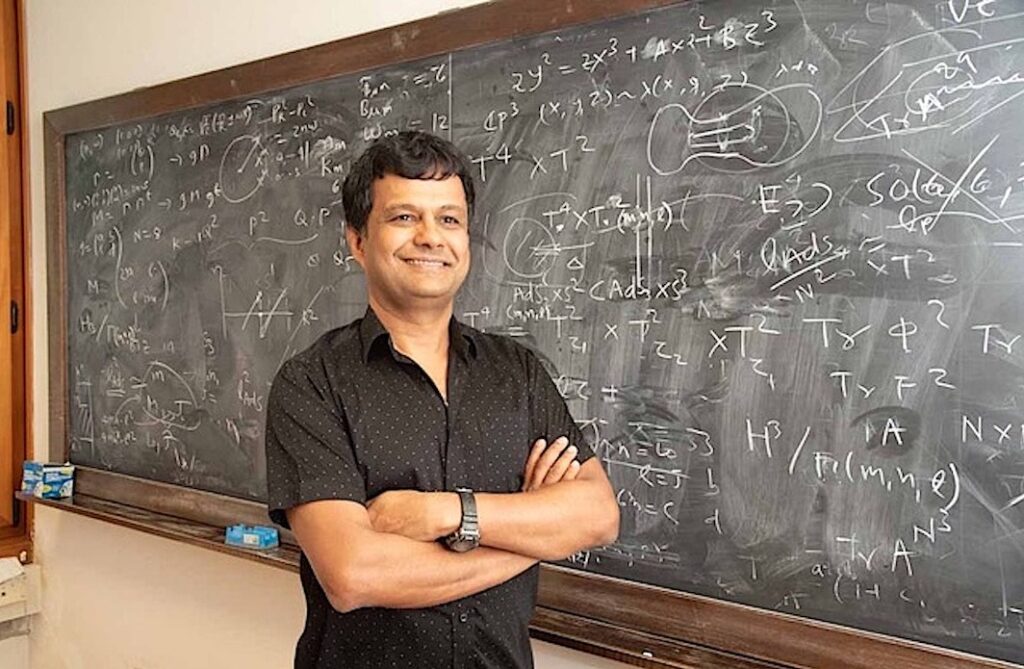

As the current director of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics, and having previously been the head of the High Energy, Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics section, Atish Dabholkar, brings both knowledge and experience to his dual role as a frontline scientist and an adept administrator. With a PhD in theoretical physics from Princeton University, he subsequently worked at some of the top research institutions including Harvard, Caltech, TIFR, Stanford, and CERN before joining ICTP in 2014 on secondment from Sorbonne Université and the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). Hailing from a small town in Maharashtra in India, and his research in string theory and black hole physics building on Salam’s work on the electroweak unification theory, it is natural for Atish to feel inspired by the ICTP founder director in his deep commitment to the cause of ICTP, sitting in the same office. In this reflective interview with Rajesh and Mahit of Bhāvanā, he recounts his journey, and future plans for ICTP – redefining itself on the momentous occasion of its 60th anniversary.

Thank you for hosting us at ICTP during its 60th year celebrations, and for agreeing to this interview.

Let us start with your first interaction with ICTP. How did it all come about?

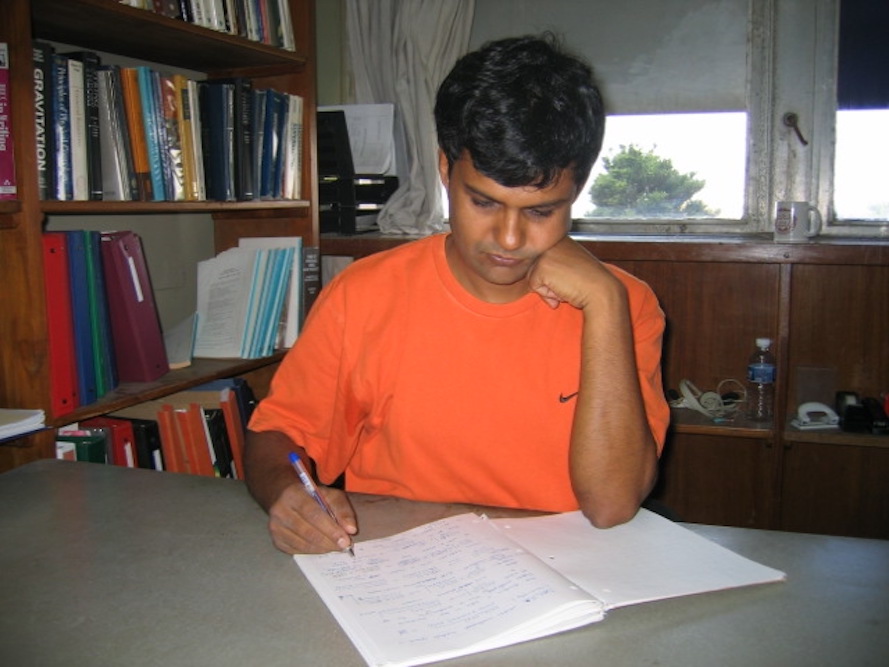

My first visit to ICTP happened around 1991–92, for a school in string theory. I had just graduated from Princeton and was a postdoc at Rutgers. This was when I had the opportunity to meet Salam. He was already quite frail and not keeping in good health, but it was great to meet him in person. Of course, I had no idea that one day I would be in his shoes leading ICTP. In fact, this used to be his office.

Oh, so this very office used to be his?

How does it feel to be in the shoes of Salam leading this major centre?

I had no idea that one day I would be in his shoes leading ICTP

Growing up in rural India, I got to see a large cross-section of the society with close friends from all strata, which I would not have seen in a big city like Mumbai. While Salam grew up in a devout Muslim household, I would describe my upbringing as basically progressive atheist.

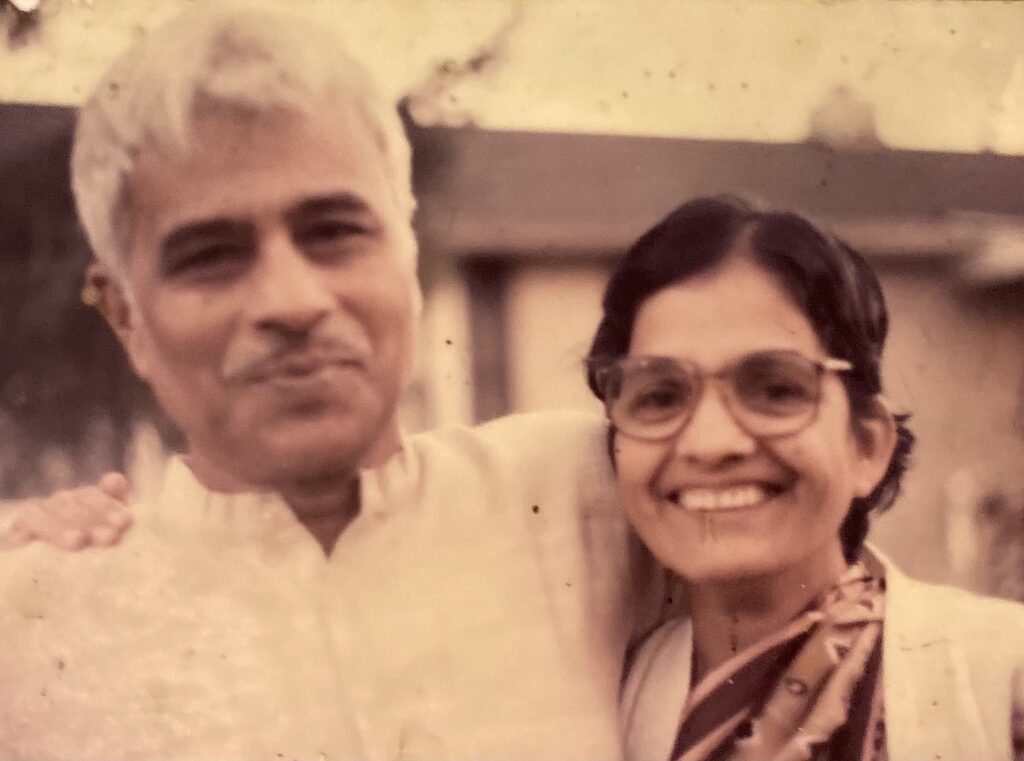

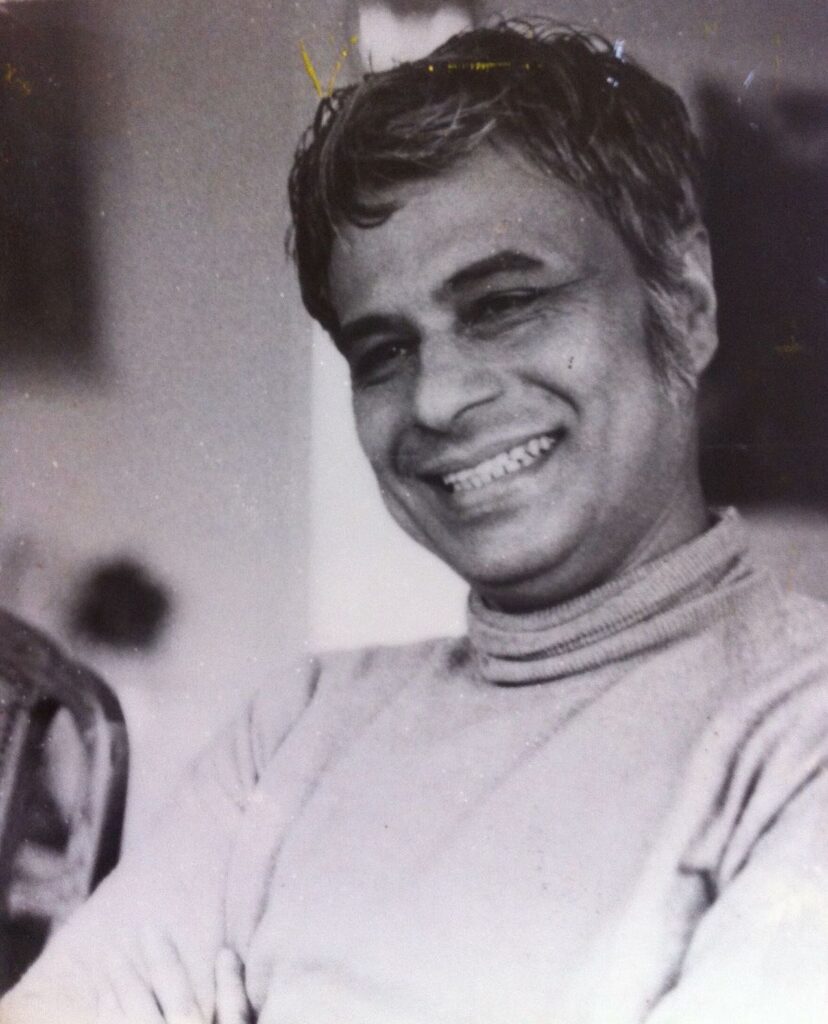

My parents were academicians but with an unusual bent, from the post-independence generation who were excited with certain idealism about national reconstruction. They worked at a new rural university that was started as a pilot project with funding from the central government, with the involvement of some of the prominent intellectuals and educationists. The motto for this initiative was `Development through Education’ – somewhat similar to the motivations behind ICTP.

My mother taught sociology and my father mathematics. He later left the university to lead an important movement which could be best described perhaps as a people’s science movement to `demystify’ science for addressing real life situations. It eventually became very successful with engagement from thousands of small farmers, many school dropouts, who organized themselves. They mastered advanced viticulture from a post-graduate level classic book of Winkler published by the University of California and adapted the science to the local conditions with many innovations. They transformed themselves into major exporters of grapes using the latest scientific know-how which had a big economic impact in the region. These contributions and his methods received considerable recognition from some of the eminent educational thinkers like J.P. Naik, Ivan Illich and Paolo Freire and with national accolades like the Jamanalal Bajaj award. These experiences were quite influential even as I pursued a career in the abstract realms of theoretical physics.

My mother taught sociology and my father mathematics

As with Salam, it was important for me to not only do good science – it was great to be in places like Princeton where I had wonderful opportunities – but also to be able to give back to Indian science and indirectly to society in some way. Psychologically, this was very important for me. So I was really committed to returning to India while I was in the US – much like Salam, who was determined to return to Pakistan.

TIFR was already an internationally recognized centre in string theory. So, I never felt that returning from Caltech in the US to TIFR in India compromised my scientific career in any way. In this sense, I did not quite experience the kind of acute intellectual isolation that Salam must have experienced and which was something which provided him with the burning motivation towards founding an international hub for science like ICTP. Nevertheless, I do share this strong internal impulse with Salam in this regard to be able to make a contribution to science in my home country and more broadly to make scientific opportunities globally available.

India in the 90s or today is not quite comparable to Pakistan in the 50s. Nevertheless, some of the main challenges for building science in the developing world still remain but in a somewhat different form. My experience of working in India gave me clearer understanding and a better perspective on some of the key issues which proved to be very valuable later in my role as ICTP Director.

How did your experience at TIFR and then at ICTP shape your thinking?

Salam was less fortunate in getting such support from within Pakistan and was compelled to leave his home country. However, with the same impulse, he founded ICTP as an international hub for science. It works towards the same goal, but in a different way, on a more global scale by making advanced science available to scientists from all corners of the world including those from disadvantaged regions.

I regard these two perspectives as being complementary to each other. When I became the director, this complementarity is what convinced me of the relevance of ICTP in the years to come. I came to the conclusion that the vision for ICTP of the future must synthesize these two in an effective way. This has been one of my guiding principles. We can discuss this more later.

What aspects of ICTP attracted you to join here as a scientist?

Even today, the Spring school remains one of the most important events on the international calendar. Leading scientists in string theory and related topics come to lecture here on the latest developments as do some of the best students and postdocs during their formative years. But the school is open to all interested students, including from the developing world with full support from ICTP for their travel and stay. Thus, it makes these excellences more inclusive and globally available which otherwise would have been restricted to only those who could afford to come to ICTP.

It is an added bonus that the ICTP campus is in a wonderful location right next to a nature park and the Adriatic sea in the beautiful and welcoming city of Trieste. This adds to the charm and you really love it when you first come here. All of this made an impression on me.

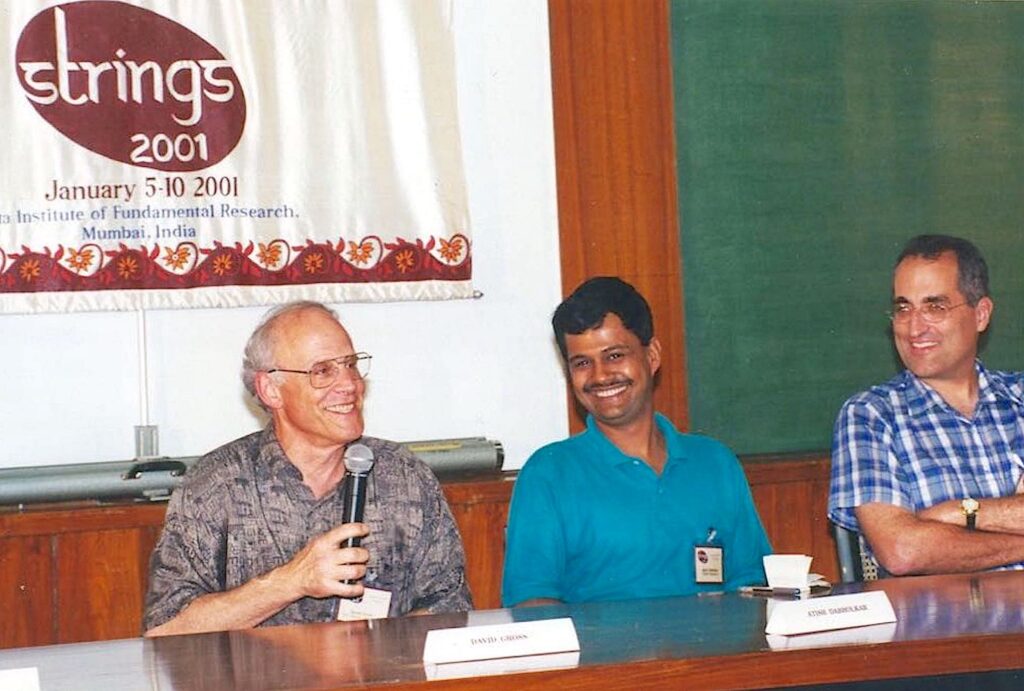

I remember visiting ICTP to seek possible funding support for this important event in India. We were grateful that ICTP immediately came forward with quite a generous grant without which it would have been difficult for us to pay for the air travel of foreign participants. Thus I once again saw the big impact of ICTP, indirectly around the world, and not only on the Trieste campus. Even remotely, it acted as a kind of lighthouse. A lighthouse for science in the developing world.

Even remotely, ICTP acted as a kind of lighthouse for science in the developing world

Wow. That’s great! What changes have you witnessed during your association with ICTP? How do you see the alignment of original goals when ICTP was started, to the present day goals?

ICTP is now a mid-size research institute. At its core, it remains a place where `curiosity driven’ blue-sky research is pursued, emphasizing fundamental sciences. Even in climate science, we are more into the science of it, like modeling and so on which can, of course, become relevant for policy recommendations. ICTP has thus grown over the years with this more diverse portfolio of subjects. However, the core mission of ICTP has not really changed but, evidently, it must now be implemented very differently.

What are the significant achievements of ICTP?

Of course, there are many places of excellence around the world. What makes ICTP special is that it makes this excellence inclusive. It makes it global. That is the biggest success of ICTP. A related component is that ICTP is truly international, being a UN organization. We can bring countries together for advanced science even when there are political differences. For example, at the height of the cold war, ICTP was essentially the only place where American and Soviet plasma physicists could meet and discuss physics. I think these are some of the biggest achievements of ICTP.

What was your thinking when you decided to take up this major responsibility as the director of this international centre?

For me, there were three critical questions. What part of the mission of ICTP still remains relevant today? What should be the essential elements of the vision for ICTP of the future, to implement this mission in the current geopolitical landscape? What effective strategy can one realistically pursue given the specific structure and mandate of ICTP? It was important to be able to answer these questions satisfactorily to myself before being convinced that it would be worth my time to take up this responsibility.

Let me elaborate a bit upon this. The need for ICTP was very clear in the 60s, because the countries in the Global South,6 which had just become independent after a disastrous and debilitating colonial rule, really had very few resources, both financially and scientifically. There was post-war optimism with a strong desire for international cooperation within the United Nations system. Moreover, theoretical high energy physics was viewed by policy makers essentially as an outgrowth of nuclear physics and nuclear energy which had a dramatic promise and therefore was a national priority for many countries. It is not an accident that research in high energy physics in many countries was often primarily funded by departments of energy. All these elements made it much easier to realize a center like ICTP in the sixties. It’s noteworthy that Salam himself was rather pessimistic about the chances of succeeding with something like the ICTP in the ambience of the eighties.

Evidently, the geopolitical situation and the frontiers in science are now radically different. Both these points require a serious reflection.

geopolitical situation and the frontiers in science are now radically different

In what ways does your vision overlap with and differ from that of Salam?

Second, as already noted above, ICTP must adequately respond to the changing frontiers of science. It was already recognized by my predecessors that ICTP must grow in other areas of science. However, there are now newer opportunities and challenges on the horizon with the developments in artificial intelligence, high performance computing, quantum information and computing. These developments have added an entirely new dimension to the notion of Open Science which must be taken into account.

From this perspective, the role of ICTP must be re-imagined. The essential inspiration remains the same for me as it was for Salam but it is natural that many aspects will have to be thought through and implemented differently. One should not merely continue by inertia with the same policies and modalities which Salam had adopted.

This introspection was quite useful for me. I came to the conclusion that ICTP is perhaps even more relevant today, and it is something where I could imagine contributing meaningfully both at the personal and institutional level.

What then is your vision for ICTP for the 21st century?

India or Brazil are not necessarily lacking in economic resources. So one cannot simply continue to parrot the rationales that were compelling at the time of Salam. ICTP must engage now quite differently, more in equal partnerships, rather than the model that was followed earlier in Salam’s time which was more uni-directional.

As I see it, the main significance of ICTP today and tomorrow is two-fold.

ICTP has a critical role to help internationalize the science even in the BRICS countries with what it can offer in terms of intellectual and scientific resources. This can be done with a greater sense of collaboration building partnerships where the financial resources can be jointly contributed. In some other countries in Asia and Africa one should engage a bit differently, not solo but with public-private partnerships involving governments, development agencies and private donors.

Another unique asset of ICTP is its global standing as an international hub for science. This is going to be increasingly important, perhaps even more so now than in the sixties, in the turbulent times that lie ahead. ICTP has the neutrality and convening power as a UN organization to bring together scientists bridging over the politics or the visa regimes. As I mentioned, even during the Iron Curtain days, ICTP was like an oasis where scientists from both sides of the curtain could come together to freely discuss science.

during the Iron Curtain days, ICTP was like an oasis

I think these two roles of ICTP, to make the excellences in science available to as broad a community as possible, remain very relevant today. Overcoming the barriers of gender and ethnicity is something that is always talked about. But oftentimes geopolitics and economics are much bigger barriers for open exchange and equity. Now we are confronting some questions with the same urgency as in the 60s but on different frontiers from climate science to artificial intelligence. For example, we have been organizing monsoon workshops at ICTP for over a decade. In these workshops, Indian, Chinese and Pakistani climatologists can come together without the hurdles from the visa regimes and geopolitical differences. Something which they are not able to do in their home countries. This is very important because monsoon or heat waves necessarily require a collective response going beyond national boundaries or political differences.

Our approach in the future should take all these considerations into account. Perhaps we can come back to it later since some of the initiatives at ICTP that we have undertaken recently are indeed informed by these considerations.

This morning, we were looking at a brochure, which mentioned the gender aspect. It was surprising to see that the statistics had a representation of women coming to ICTP from different parts of the world, but India does not figure in the top 10 countries in this category, though a lot of male students are coming to ICTP apparently.

What were the major challenges you faced when you took over, and how have they been addressed?

Yeah, Italy was affected badly.

Since there were no visitors, we decided to use the Adriatico and Galileo guest houses as a student dormitory. In some ways, for the students it was like being in a very nice prison far away from home because they were not allowed to even leave their rooms. Some had food restrictions like halal, some would crave for home food after a few days, some had psychological difficulties from loneliness and anxiety. We had to handle all this, in many ways like their local guardians. I have to really thank my colleagues, both academic and administrative, who helped make it happen, successfully graduating 200 students from over 100 countries during these difficult two years.

Post-COVID, what have been your priorities?

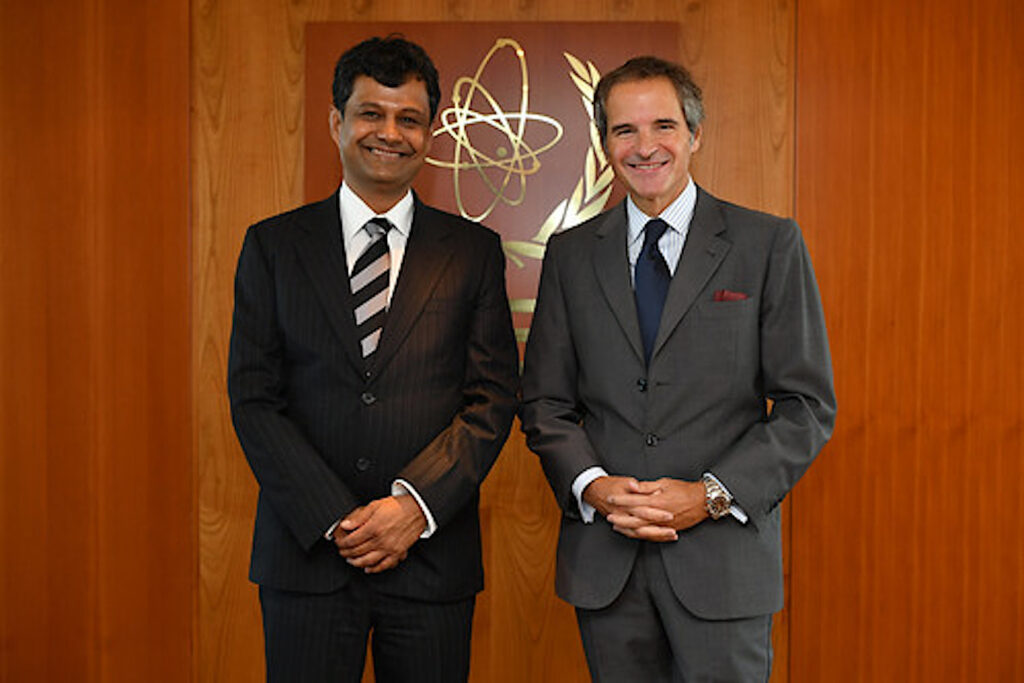

Addressing this issue required a much greater investment of time than what I had anticipated because of the particular governance and administrative structure of ICTP. ICTP is governed by a high level international Tripartite Agreement between the Government of Italy as the host country and two UN organizations – UNESCO, and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). For our first thirty years, we were administered within the IAEA and since 1996 we have been administered within UNESCO. This governance structure has been very beneficial to ICTP since it confers the status of a UN organization. At the same time, it presents some challenges, because some of the organizational needs of a leading scientific institution like ICTP oriented towards scientific research can be quite different from the needs of the rest of UNESCO which is oriented more towards policy. If this difference is glossed over, as it sometimes was, it can lead to disastrous policy decisions.

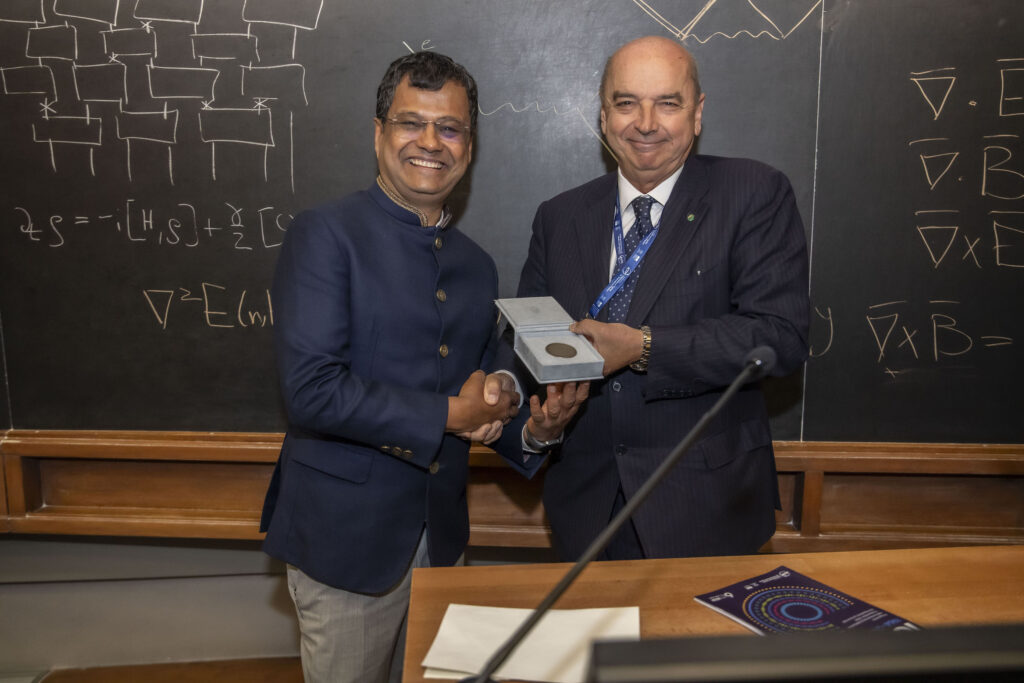

I am very happy that in the end all these efforts were worthwhile. In collaboration with some colleagues at UNESCO, we were able to successfully resolve this issue. Very strong support from the Scientific Council, as well as from the Italian government and IAEA who are the other members of our steering committee also played a crucial role. Together, we managed to upgrade more than one third posts at ICTP to be more commensurate with the actual duties. This very substantial upgrade of our human resources was a major accomplishment for securing the future of ICTP. I was quite relieved because otherwise ICTP would have surely lost much of its attractiveness and lustre.

The second challenge has been to find the means to consolidate and expand our physical resources. The ICTP infrastructure is now 60 years old and is showing its age. We need modern infrastructure commensurate with the global standing of ICTP. Furthermore, some of the more ambitious ideas we have in mind for expanding our scientific mission will also require more funding. ICTP has been generously funded thus far by Italy, UNESCO and the IAEA, but the funding has remained constant and has not been inflation-adjusted over the past three decades. Evidently we need to look for new resources and cannot rely entirely on the generosity of public funding.

Recognizing these needs defined my second priority. We have started a very professional advancement and fundraising initiative to tap into new resources. We also have a high profile Advisory Board including people like Ashvin Chhabra, Thuy Dam, Michael Douglas, David Gross, Andrea Illy, Princess Sumaya of Jordan, Ahmad Salam. They are all actively engaged with ICTP. These efforts are also now bearing fruit and new funding is becoming available in a major way. So much so that I hope in ten years’ time this could change the equation for ICTP completely, bringing substantially more resources to ICTP than are currently available. We are therefore quite ready to start thinking about expansion.

How do you envisage the role of ICTP in the future consistent with your thinking and what are some of the new initiatives?

(2) There is a greater need to ensure equitable opportunities in the ongoing scientific revolution and technological advances like high performance computing, machine learning or quantum computing. This is a completely novel dimension of Open Science which now must include a notion of open access to computational resources and knowhow, open codes and open weights of trained algorithms. It cannot be good for the world if these precious intellectual resources remain locked with a few countries or a few corporations.

(3) There is a greater need to ensure essential global participation to address global challenges like climate response. This existential threat to humanity does not respect national boundaries. At the same time, climate research is often constrained by geopolitics. For an effective global climate policy, it is paramount that those who are most affected are part of the science that informs policy.

This articulation suggested to me three strategic priorities for ICTP.

(i) ICTP 2.0: Reinforce the existing competencies of ICTP, and build upon these core strengths by attracting the best talent to ICTP. Modernize both the physical and scientific infrastructure of the Centre.

(ii) International Science Alliance: Build partnerships with foundations, governments, corporations and private donors from around the world to deliver more effectively on ICTP’s programs by bringing in new sources of funding.

(iii) International Consortium for Scientific Computing: Develop an institutional framework and partnerships for Open Computing.

Can you elaborate on what you mean by ICTP 2.0? What are some of the steps in this direction?

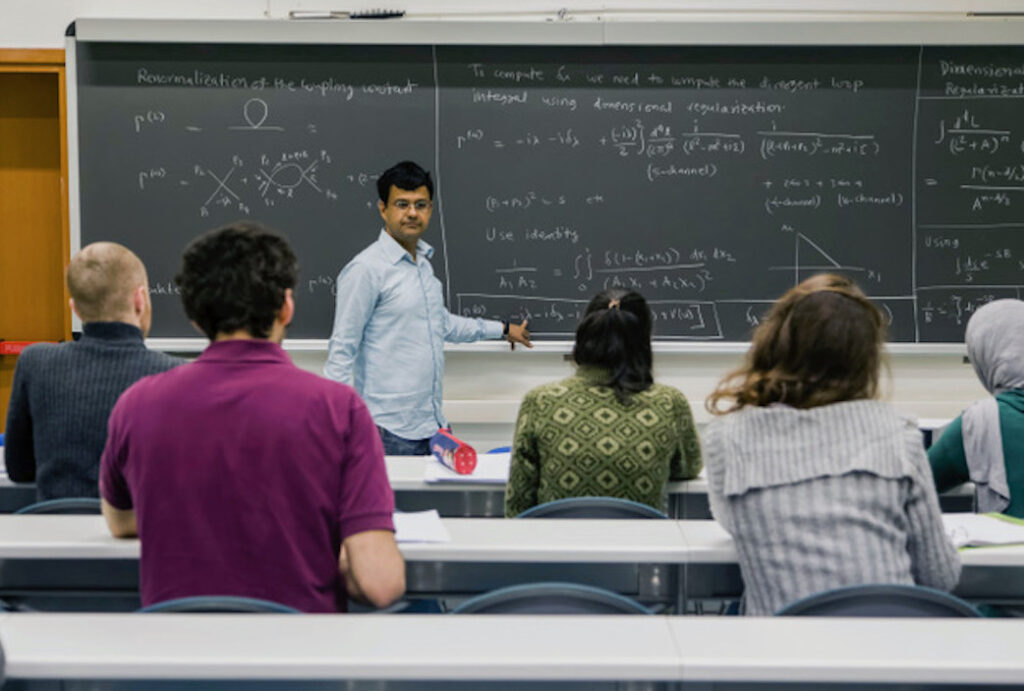

For any organization, the most important resource is people. For a scientific organization it is all the more important to find the top talent doing the most exciting science and to ensure working conditions that are welcoming. As I mentioned, securing the promotions of our scientists was therefore an important first step. Evidently we need to continue along this path, actively seeking out the best talent in the frontier areas. I am also glad that we are now beginning to change the gender ratio as we make new appointments. The fraction of women among the professional staff has increased from \frac{1}{5}th to \frac{1}{3}rd in the past five years with some excellent scientific appointments.

The frontiers of science have also changed. We are no longer looking for the Higgs particle. In addition to particle physics, there are exciting observational projects like the Square Kilometer Array or gravitational wave telescopes of relevance to primordial cosmology and astroparticle physics. The theoretical explorations could also be oriented towards understanding machine learning, or the new developments in quantum information theory and computing, or neuroscience or automated proof verification or the fascinating connections between quantum entanglement and spacetime geometry. These are exciting frontiers.

For any organization the most important resource is people

We also started the new programme of International Chairs whereby renowned scientists can spend a total of one year at ICTP so that our global community can benefit from the scientific interactions with them. So far we have had Don Zagier and now Carolina Araujo as the Ramanujan Chair, Subir Sachdev on the Virasoro Chair and Sergei Gukov on the Mirzakhani Chair.

Of course, it is equally important to upgrade our infrastructure to offer world-class facilities to our global community. This is also a part of our thinking for ICTP 2.0.

What are the biggest successes for ICTP 2.0 on that front under your leadership?

The grant from SFI will enable us to achieve this goal. The grant is structured in an interesting way as a challenge to raise a matching 15 million in five years. It is one of our ambitious goals to raise these matching funds, and I’m reasonably optimistic that it will happen. That will really change the way we operate. We are grateful to SFI and their President David Spergel for this generous support.

Another very important development is our project for modernizing the Library. This has been a public-private partnership with some funding coming from Italy and some from friends of ICTP like Drs. Ashvin Chhabra and Daniela Bonafede-Chhabra. The paradigm of a library has now completely changed around the world with digitalization. It is no longer merely a place where books are stored but rather a space for creative thinking and collaboration. We managed to flip our collection so that now our library has over 50K digital books in addition to 50K physical books. All ICTP associates from anywhere in the world get to legally download any of these books and keep them. This is a wonderful implementation of “open science”.

All these developments have been tremendous for ICTP, and are going to be truly transformative.

What about the International Science Alliance?

Now, my efforts have been to think a bit differently at the national or regional level to build an `alliance for science’. Such umbrella agreements with a national-level funding agency or a ministry or a foundation can broadly benefit anybody from that country or the region with real funding. It is also more efficient since we don’t have to work with several individual institutions.

We are currently discussing the modalities with President Galvão of CNPq. If Brazil makes a substantial contribution within the framework of this agreement, ICTP is of course not going to keep the money for itself. If somebody gives an X amount of money, ICTP contributes Y, both directly and in-kind. It’s a win-win situation with a multiplier effect. We have over 6,000 scientists coming from over 100 different countries every year. And we get about 30,000 applications. So, as such, we cannot accommodate all as we have only limited resources. With the International Science Alliance, it would be easier for us to increase the number of scientists or increase the number of students coming to our programs.

I think that this is a new direction that ICTP has taken and we are beginning to see some success. We have taken important steps also with South Africa, Rwanda, Vietnam, Indonesia, China. I do want to realize something like that with India. I have been talking to the Secretary of the Department of Science and Technology Abhay Karandikar, and also the Ministry of Environment and other colleagues. I am optimistic.

It has been heartwarming to see also the support from the scientific community itself for supporting the initiatives of the Alliance. Just during the past year, we have been fortunate to receive over a million euros collectively from several scientists or former scientists connected in some ways to ICTP, including from many of the leading lights. This is a strong validation of the mission of ICTP.

The International Consortium for Scientific Computing sounds like a very important initiative. What progress have you made on this front?

Now, this is something that ICTP cannot really deliver on its own. It’s too big a task. Which is why we launched the International Consortium for Scientific Computing, ICOMP9. Some of my colleagues at ICTP like Sandro Scandolo have played a crucial role in these developments. ICOMP is conceived not as a Centre or a section but as a consortium transversal to all sections with many partners. For example, we now have agreements with South Africa, with their national supercomputing facility and the National Centre for Theoretical and Computational Sciences (NITheCS). This will allow any scientist in South Africa, irrespective of which university, to come to ICTP and benefit from the programs offered here. We have an agreement with IBM to launch two major schools and two major prizes each year in machine learning and quantum computing. We have an agreement with CECAM (Centre Européen de Calcul Atomique et Moléculaire),10 one of the international supercomputing collaborations based in Switzerland to make computing resources available to the developing world.

This initiative can really help to connect the global north and the global south to make new technologies like GPU, Artificial Intelligence, or Quantum Computing broadly available and to address critical problems like climate response.

It is essential that the global south is sufficiently prepared with a strong scientific community. This is very important for downstream applications. For example, you may have a sophisticated climate model using GPU programming or AI developed in the Bay Area or in Bologna. However, if one wants to predict the rainfall in Ghana (whose economy depends heavily on hydro-electricity) for policy recommendations, it is essential that there is a climate and computational community in Ghana who are part of the creation and implementation of this model adapting it to the local conditions. Otherwise, it would be like a black box and one cannot have the public trust and support for the national policy decisions that follow from it. Both the International Science Alliance and ICOMP can play a role here and I think ICTP has a special niche given our global network of scientists and track record.

And what about the lab facilities here?

We have a computing facility with the `Argo supercluster’ which is important for our programmes for high-performance computing for training and development. For actual computations, we have an agreement for cloud computing with CINECA (Common Infrastructure for National Cohorts in Europe, Canada, and Africa),11 the national supercomputing facility in Italy which is among the top in the world. With ICOMP, we would like to see that these resources grow both for training and development onsite, and for cloud computing.

We also have a Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) unit. It’s a relatively small unit but they do a lot of interesting and creative things such as low-cost measuring devices in collaboration with CERN, and with IAEA, which are very useful in the developing countries. For example, for climate modeling, you need data for simple parameters like temperature and humidity but with a large coverage. Even if you have a sophisticated climate model, without this data for initial conditions, it cannot be sufficiently predictive. Large parts of countries in Africa which are not covered adequately, low-cost instrumentation of the kind that the STI unit provides can surely help to improve the coverage. So ICTP has some role to play in these directions.

Do you feel that the location and ambience of ICTP has been an important factor in attracting people?

it’s a stroke of good luck that our campus is at this amazing city like Trieste

In fact, when people were looking for a place for ICTP, there were many possibilities. ICTP could have gone to Florence, for example, which is also a special city but perhaps not from a practical point of view. In an expensive big city, bringing in 6000 scientists would have been challenging with a major cost overhead. Being where we are makes the logistics a lot simpler. Apparently, Trieste received support from the non-aligned countries including Yugoslavia and India because of its geographic location at the East-West border. In some ways, the character and history of Trieste as a city at the East-West frontier rhymes with the international spirit of ICTP. The natural beauty of the location also adds to the charm of the ICTP experience. People remember their stay here even 20 or 30 years later not only for the science but also for the experience.

Shifting gears a bit, and since Bhāvanā has a focus on mathematics, we would like to hear about your collaboration with Sameer Murthy and Don Zagier, and about the book you are writing.

Recall that a classical modular form is a function of a single `modular’ variable \tau. A Jacobi form is a generalization to a function which depends on an additional `elliptic’ variable z and thus is a function of z and \tau. The theory of Jacobi forms is very well understood when they are holomorphic in z. There is a classic book by Don Zagier and Martin Eichler on the topic. Since we were naturally encountering these objects in our investigations about black holes, I had organized a conference in Paris together with Boris Pioline on this theme of `Black Holes and Modular Forms’. The idea was to bring together physicists and mathematicians who otherwise would not talk to each other. I didn’t really know Don at the time, so had invited him just on a hunch which turned out to be quite fruitful.

This was in Paris.

So none of you were part of ICTP at that time.

to bring together physicists and mathematicians who otherwise would not talk to each other

I enjoyed working with him because in some ways he thinks like a physicist. He really wants to compute things. He is very hands-on and not an abstract mathematician like someone from the Grothendieck school. On his 65th birthday, when I was invited to give a talk, I started with the quote from Freeman Dyson who had said that mathematicians are of two kinds. There are birds like eagles who have a panoramic view of deep mathematical structures and then there are frogs, who love the specific mathematical details 14 It is not intended as a pejorative but as a description of the style since Dyson considered himself or someone like Ramanujan a frog. And of course there are some like Euler who are perhaps both. I would say he is a frog extraordinaire.

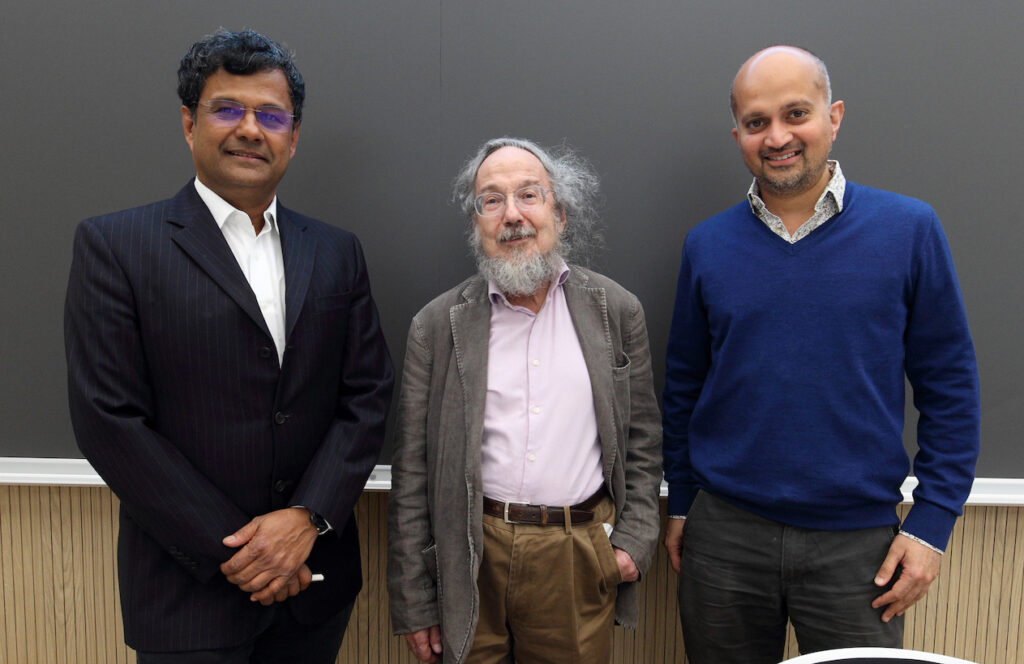

ICTP did play a role in many ways. As I said, I met Sameer here for the first time. Then Don and I joined hands once to organize a two-week long school at ICTP on modular forms and physics. So ICTP should get some credit for our collaboration. We continue with the writing of the book which is still not finished. And the three of us have continued to collaborate on different topics where physics and number theory meet. So I think it has turned out to be a very fruitful collaboration.

What exactly is a mock modular form and why was it so mysterious?

A mock modular form is holomorphic but not obviously modular. What makes it interesting is that it is `secretly modular’ in that one can add to it a non-holomorphic `correction term’ to obtain its `completion’. The completion is modular but is no longer holomorphic. This secret modularity and the incompatibility between modularity and holomorphy is the essence of mock modularity.

To give a geometric analogy, a holomorphic modular form is like a blue circle. It is both blue and circular – invariant under the symmetry group of rotations. A mock modular form by contrast is blue but is not quite circular. It is rather like a circular arc which lacks the symmetry of a circle but in an interesting way. One can add a missing arc or the correction to obtain a complete circle as its completion. However, imagine that this correction piece must be red for some reason. As a result, the completion, even though circular, is no longer fully blue. Thus, there is a secret circularity if one is willing to give up on blueness, and there is an incompatibility between circularity and blueness.

What was magical about Ramanujan’s discovery was that he was able to grasp the secret modularity underlying the mock theta functions without explicitly knowing about their completions. This is what made these objects mysterious until the theory was developed by Zwegers.

What were the main results of your collaboration from the perspectives of both mathematics and physics?

Sameer and I found a beautiful physical interpretation of this main theorem. It turns out that the Fourier coefficients of the mock Jacobi form count the number of microstates of single-centered black holes and the Fourier coefficients of the Appel–Lerch sum give the number of microstates of multi-centered black holes. So many of these mathematical objects in the story turn out to have a nice physical realization.

The mock Jacobi forms, like the mock modular forms, are not quite modular, but by adding a non holomorphic completion term, one can obtain the completion which is modular. The assertion that such a completion exists was the nontrivial part of our theorem.

The apparent lack of modularity of the mock Jacobi form is what had bothered me to begin with. For a mathematician like Don, modular symmetry is something sacrosanct, and seeking the modular completion was quite natural. However, one can ask why physics should care about modularity, or the modular completion. My motivations were quite different coming from what is known as holography. In this particular context, I knew that the {\rm SL}(2, \mathbb{Z}) modular symmetry must be a part of global diffeomorphisms because of holography. Diffeomorphism invariance cannot be violated in a physically sensible theory of gravity. Thus, the modular symmetry turns out to be sacrosanct also from a physical point of view. Thus, these very different motivations turned out to be closely related.

The physical origins of this apparent lack of modularity were still not completely clear. In a subsequent paper with Putrov and Witten, in a quite unrelated context, I was able to relate mock modularity to the non-compactness of field space of the underlying path integral for a conformal field theory to get a better physical understanding of mock modularity.

What would you say about this kind of a collaboration between mathematics and physics?

It’s not always easy to strike such a successful collaboration in such widely disparate fields. Sometimes the tribal pride of being a physicist or a mathematician comes in the way. I think it’s a bit like learning a new language. One has to be a bit adventurous, prepared to sound silly like a beginner and willing to listen, and not be overly embarrassed about making mistakes to learn a new language and then start speaking it fluently.

And is Don visiting ICTP sometime?

So ICTP now has a major centre in Brazil and South Africa.

Is there a possibility of having such an arrangement in India too?

The really important thing is not so much to go for a centre, but build a partnership with scientific exchange first. One really needs to understand the needs and the funding situation, local support, support from the government, and the available leadership and human resources. If any one of these components is missing then it can become a difficult operation. I do hope that we succeed in developing a major collaboration with India as I have had with Brazil and one can then think of more ambitious projects within that framework. I think it’s very much a possibility, and I would really like to see it happen.

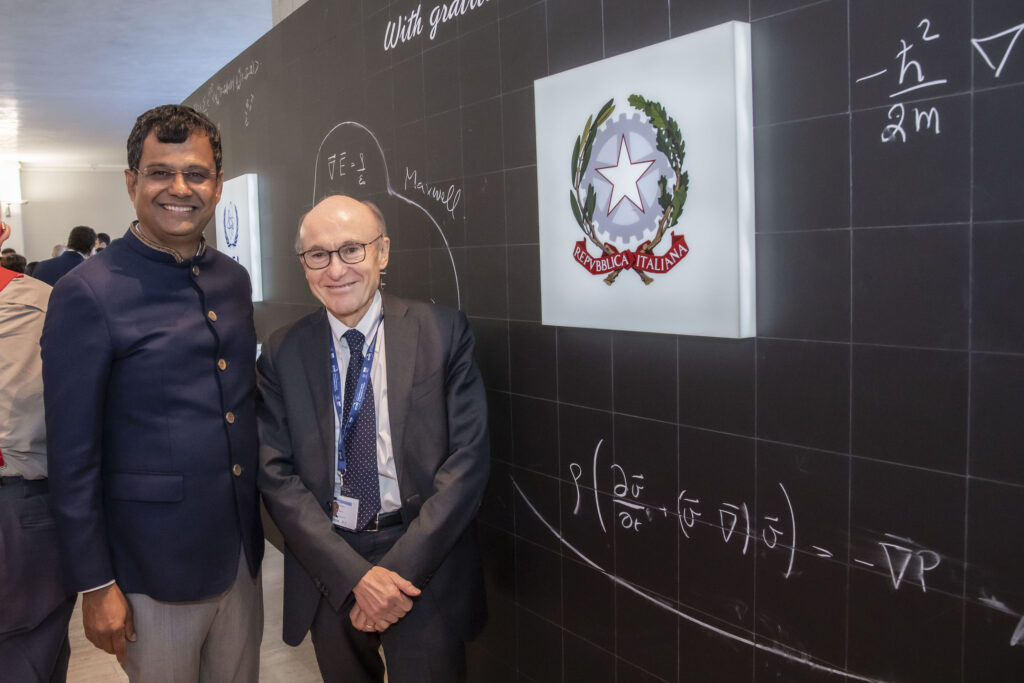

Can you give us a brief overview of the events during the 60th anniversary year of ICTP?

Were there any important takeaways from the programme?

Is there something else you would like to add about your experience and about ICTP?

little I’ve been able to accomplish has been deeply satisfying

I have a second mandate now for another four years. I hope that we are able to allow ICTP to grow and be an even bigger force in the 21st century and have a much bigger impact. The 60th anniversary was an occasion to imagine ICTP in 2064. Some of the ideas and our vision I have are outlined here and also in my presentation during the celebrations in Trieste.

You mentioned that you are working on getting funding and working with the stakeholders like Italy, UNESCO, IAEA. This must be taking away time that you would have spent in research, and possibly some of your other avocations. How do you manage to segregate your time for them?

One of my main hobbies is Indian classical music. I play the north Indian classical violin. I have been a disciple of Pandit Atulkumar Upadhye from Pune for many years and try to keep it going. Amir Khan, Kumar Gandharva, Kishori Amonkar, Bhimsen Joshi, Nikhil Banerjee, Vilayat Khan are some of my favorite classical musicians. Swimming in the Adriatic and hikes in the Alps near our home in Slovenia are some other modes of relaxation.

It’s indeed a challenge to combine different things in life, but I think it’s a matter of time management to find a balance. You learn to do that at different stages of your life. I guess everybody does it in their own way to balance their time for science, for personal life and for society.

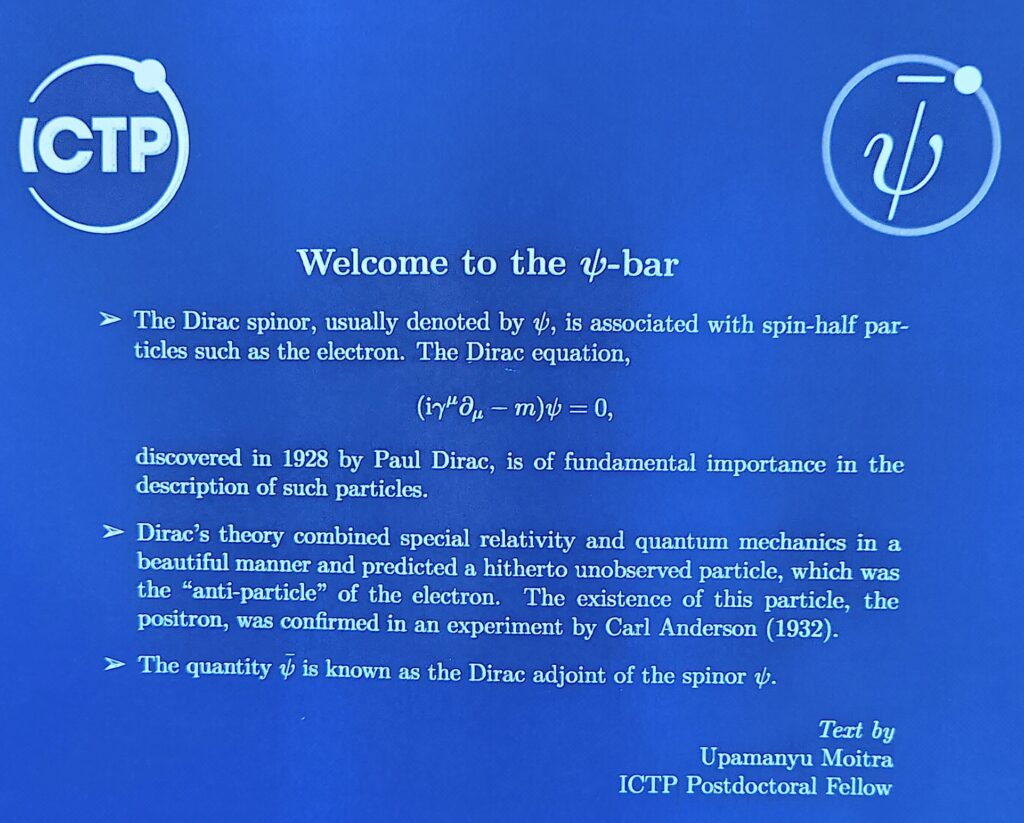

One other thing we were just noticing is that the Adriatico bar is called Psi bar, and the bar here at Leonardo is called H bar. And then there are spaces here, which are called Hilbert space. Is this something that has been there from the beginning?

Looks like the bar at Galileo guest house is still missing a name.

I play the north Indian classical violin

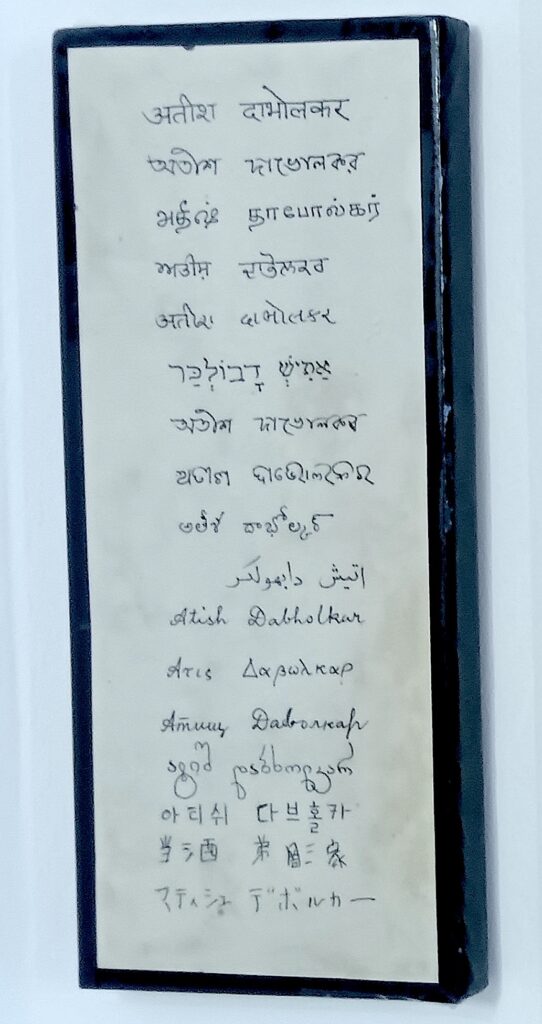

And your nameplate is interesting too. Your name is displayed in many languages! We were delighted to see that.

That is great! Thank you so much once again for inviting us. We are enjoying our stay very much.\blacksquare

Footnotes

- More on this event can be read here: https://theory.tifr.res.in/strings/. ↩

- Cosmic sciences refers to the study of the universe on a large scale, including its origin, evolution, and structure, essentially encompassing fields like cosmology and astrophysics. ↩

- Practical sciences refers to disciplines focused on applying scientific knowledge to solve real-world problems, like engineering, medicine, and agriculture, which are more grounded in immediate, tangible applications. ↩

- https://www.ipcc.ch/about/. ↩

- This stands for `A Toroidal LHC Apparatus’, and is the largest general-purpose particle detector experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). ↩

- According to Britannica: The Global North–Global South system is frequently used interchangeably with the system of more and less developed countries by the United Nations and other such groups. Most commentators typically include in the Global North the United States, Canada, the countries of Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel. The Global South usually includes the countries of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East excluding Israel, and Asia and Oceania excluding the aforementioned countries. ↩

- https://www.ictp.it/news/2024/7/new-ictp-brazil-collaboration. ↩

- The Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) is an organization of the Brazilian federal government under the Ministry of Science and Technology, dedicated to the promotion of scientific and technological research and to the formation of human resources for research in the country. ↩

- https://www.ictp.it/home/consortium-scientific-computing. ↩

- https://www.cecam.org/. ↩

- https://www.cineca-project.eu/. ↩

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1208.4074. ↩

- Carolina Araujo is currently the Ramanujan International Chair. ↩

- This paper titled “Birds and Frogs’’ is published in “Notices of the American Mathematical Society’’. https://www.ams.org/notices/200902/rtx090200212p.pdf. ↩

- Don Zagier is currently Distinguished IGAP (Institute for Geometry and Physics, https://www.igap-ts.it/) Professor at ICTP. ↩

- V.A. Fock is a twentieth century Russian physicist who did foundational work in quantum mechanics. There are many eponymous discoveries, like Fock space and Fock representation, named after him. ↩