Dear Professor R.P. Bambah, thank you so much for this opportunity. It’s a great pleasure, and an honour for us to be talking to you.

RPB:Thank you. It is indeed my pleasure too.

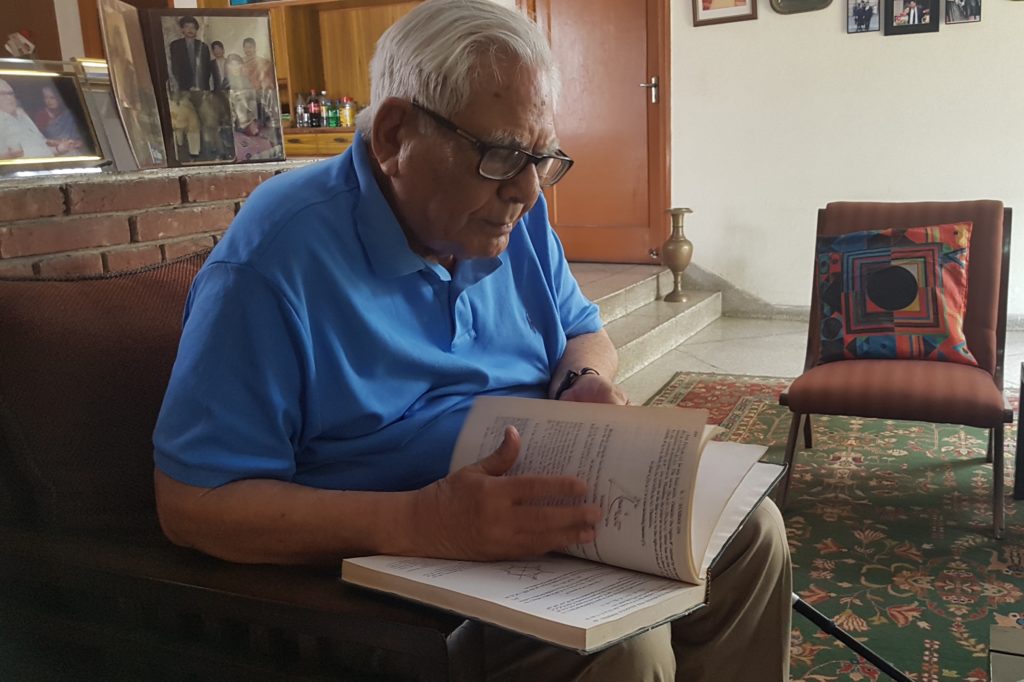

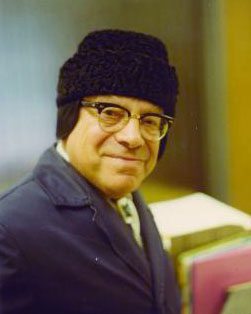

How often does one get to meet somebody who, at a sprightly 94, has been at the forefront of research, teaching and administration, and also has built up a top university mathematics department like the one at Panjab University, in addition to holding the high office of such a university as its Vice-Chancellor?

RPB: The credit for nourishing the mathematics department goes to Professor Hansraj Gupta too. He and I started the department. He was already a Professor, and I was still a Reader, but we worked harmoniously together as a team. As a result, we were able to do something substantial, and primarily, also because he did not have any ego. He was a very generous person.

I completely agree that in order to build an institution while keeping in view a long-term vision, it really calls for that kind of attribute–-generosity and patience–-and as you said, no ego. Absolutely right.

Professor Bambah, I want to start from the very beginning. We learn that your family was originally from an area that is presently in modern-day Pakistan.

RPB: Actually our family was from Jammu, but my father spent most of his life in present-day Pakistan, till the Partition.

Was it from the Jhang area of Pakistan’s Punjab?

RPB: Not from Jhang. Our family lived sometime in the past in Jammu, and before that, we lived in a place called Wazirabad between Jammu and Lahore, and then for some other time in Sialkot near Jammu. These are the places where our family went to and lived in. My great-grandfather was at Jammu. My grandfather was born in Jammu. My father was born there, and I too was born there. [Laughs]

So there is a long familial association with Jammu!

RPB: Jammu is in India, of course. But before Partition, my father was mostly in some parts of Punjab, and Balochistan. Both those parts are now in Pakistan.

Could you please tell us a little bit more about your childhood–-your parents and your family background in general when you were growing up?

RPB: Well, I was born in Jammu but like all old-timers, there is no birth certificate of any kind, but I do believe that I was born on the 30th of September, in 1925. My father was then posted at Quetta. My parents were married at a young age. I had two elder sisters. My mother had already had five children before me, of which sadly only two survived, and three died in infancy. So, I was the sixth child. My father was posted to a place called Qilla Saifullah which is close to Afghanistan, and they were there for many years, and then he left for Quetta.

When I was three or four years old, my father decided to take me to school. It was a school near our house, run by the Dayanand Anglo-Vedic Movement, called the Arya School, I think. The school had classes held in separate rooms, where the students sat on mats spread out on the floor. Each class had long jute mats, perhaps five or six of them, laid out side by side. You started on a mat laid out on the extreme right of the class. If your performance was good, you would move to the mat on its left. I believe I moved three mats leftwards, in a period of two or three months that I spent there. And then my father got transferred to Punjab, to a place called Wazirabad, which was a township with a population of about 25,000 at the time. There was no electricity, but it was a big station on the main rail route connecting Peshawar to Calcutta and Bombay. This was a rail line that connected Calcutta, Lahore, Wazirabad, Peshawar and Bombay. From Wazirabad, there were also many smaller rail links going to Jammu, Lyallpur and so on. So Wazirabad was a big train junction, but a small place.

We were there for about six to seven years, and I went to school there. So that is where my schooling started–-the first three months in Quetta, and then six years in Wazirabad.

Was it also a DAV school at Wazirabad?

RPB: No. The DAV school was in Quetta. In Wazirabad, it was a municipal school named M.B. Primary School, i.e. Municipal Board Primary School.

Did you already find mathematics interesting while in school, and were you also mathematically precocious for your age?

RPB: I believe I was faster than the average student in my class and used to understand things fast. So much so that after the second year primary, the school teachers came to my father, and asked “Why are you wasting his time? Let him skip the next grade and go to fourth grade straight.” So they made me skip a year and put me in fourth grade.

In the fourth grade, there was this scholarship examination, and they put me up for the scholarship. That examination was by elimination, and administered subject-wise. The first subject was mathematics, and I believe that I finished the said exam very fast, and gave my answer books to the teacher in charge. They were surprised, and when they checked it, they found that my answers were all correct. Speed was my main forte, and then I passed through the various stages, but I was sadly eliminated at the “Urdu Dictation” stage. My teachers didn’t believe it, so they went to check my answer book, and they found that I had indeed made lots of mistakes. So, I didn’t get the scholarship.

And then from primary school, I went to the Municipal Board (M.B.) High School, and I was there for two-and-a-half years.

What was the medium of instruction in early school?

RPB: Urdu.

Can you read and write in Urdu, written as it is, from right to left?

RPB: Yes, all those things seem to have come naturally to me. That’s why they pushed me up.

Were you also taught at home?

RPB: No. My mother was not educated, but she had been to a Gurdwara school where she learnt to write Punjabi, and also to calculate. She was able to calculate very fast. I think she could easily have been better than me, in the sense that she would go shopping for two-and-a-half yards of cloth, at three-and-a-half rupees per yard. Before the shopkeeper could, she would give him the money, and also ask for the correct change. She was good at that, but she was not otherwise educated.

That must have come down naturally to you as well. Could you tell us the names of your parents, please?

RPB: My father was Bhagat Ram, and my mother’s maiden name was Durga. She was called Durgo by her parents, and after marriage she became Lajwanti. Much later, it got truncated to Lajwati. When my sisters grew up, they felt that ‘wanti’ was not right. Punjabis use ‘wanti’. In Hindi, they just make do with ‘wati’. So she became Lajwati.

During those early years of schooling your teachers noticed that you were faster than the rest of the class. Do you recall any of your teachers from that time who made a lasting impression on you?

RPB: Yes. Once–-I think this must have been in the sixth class or so–-some homework was given by the teacher. I completed it fast, but it was messy–-bad handwriting, and the work was also not too neat. I took it to the school, and the teacher looked at it and slapped me. I asked why. He said, “You wretched fellow! If you could do it a little neater, you would stand first in all of Punjab.” I didn’t know what standing first in Punjab meant. But this incident I still remember very vividly. Then when I was in the seventh class, my father got transferred to Sialkot, which lies between Jammu and Wazirabad, and he took me to a school there. This was Arya High School in Sialkot, whose principal was Prof. Inder Singh Luthar’s father. You might have heard of I.S. Luthar!

Luthar, yes. I am aware of the algebra textbooks that I.B.S. Passi and he have jointly authored.

RPB: Luthar is seven years younger than me. His father’s name is Hari Ram. My father showed him the school leaving certificate from school, which had obviously mentioned something good about me. The Headmaster said, “Well, you have come from a village school. Let’s see how you fare here.” But within a few months, they saw in me a bright student, and the headmaster even remarked to somebody that I was the best student he had seen in his life. There was also a mathematics teacher by name Narayan Das. He was very straight-forward, always to the point, and he encouraged me a lot. Between the two of them, they gave me a lot of encouragement. Then during the eighth grade, there was again a scholarship exam for the district, and they put me up there. This was in Arya School and the medium of instruction was Urdu, but at that time there was a certain feeling that I should move to Hindi medium. In our enthusiasm, those of us who had done well opted for Hindi.

So you moved to Hindi medium there.

RPB: The examination was in Hindi, but the instruction we had was still in Urdu. So when we saw the question paper, we didn’t understand any of the questions. It was very difficult. In mathematics, which was my pet subject, I was very confused. In the same exam hall, there was another question paper, this one set in Urdu. Under every question posed in Urdu in that paper, they had an equivalent English term. For example, perpendicular would be `lumb’ in Hindi and `amud’ in Urdu. I could see `amud’ there, and `lumb’ here. So I answered the question, writing Urdu words, but in Hindi script.

So your familiarity with Hindi and your quick thinking came in handy.

RPB: I had Hindi as a subject in school. Hindi was not the medium, but one of the subjects. Eventually, I did make the scholarship. I stood second in the district and got the scholarship, in spite of the confusion caused by the combination of Urdu and Hindi. I spent grades ninth and tenth in Sialkot. In the meantime, my father got transferred to Lahore, and so we moved to Lahore. When the results came, I had done pretty well. I had stood 10th among 40,000 students.

That’s quite an achievement.

RPB: I was ninth in rank. The topper had scored 730. I got 709 out of 850. I was disappointed with my scores but still had a scholarship. My teachers also thought that I should have done better. One of my friends, who has been a great friend all my life, had scored 711, two marks more than me. English was my weakest subject, where I got 134 marks out of 200. This was still first class, but it was much less compared to other subjects.

That must have comforted you a little bit.

RPB: Yes. I was among the top 10, and there were 40 scholarships. Then one of my relatives felt that I had the potential to get into the much-coveted Civil Services. He encouraged my family to admit me to the famed Government College at Lahore, which by the way, we couldn’t really afford then. But I still earned admission to the Government College at Lahore. The roll number was assigned according to one’s marks. I was roll number 5. By the way, most of the first ten rankers came along to that college, and the roll number of this great friend of mine was 4. So we were together that way when we started in college.

What was your father by profession?

RPB: My father was then a Railway Guard, and later on, he became a Yard Master. He retired as Chief Yard Master.

That’s why you said you couldn’t afford the fees, coming from a humble background.

RPB: Yes. The scholarship was 18 rupees, and my father’s salary was 64 rupees, or something like that. The fee was 12 rupees or so; that way one could save around 6 rupees. It was hard on the family, but they thought that it was a good investment in me, in the sense that they thought that I would do well.

You were already doing well.

RPB: I had a scholarship already, and was also staying at home. There were other colleges who were willing to give me free admission, free food, and so on because they wanted good students. Government College at Lahore didn’t bother with any of that, because good people came there by themselves. Getting admission was hard even with decent marks.

See, this was also the college where Prof. Sarvadaman Chowla was teaching. This was the college where Abdus Salam went to, and where Hargobind Khorana went to as well. That’s two future Nobel Laureates right there, for you. The general impression was that if you are in Government College, Lahore and if you did well, then you could get a government job very easily. That’s why they sent me to that college.

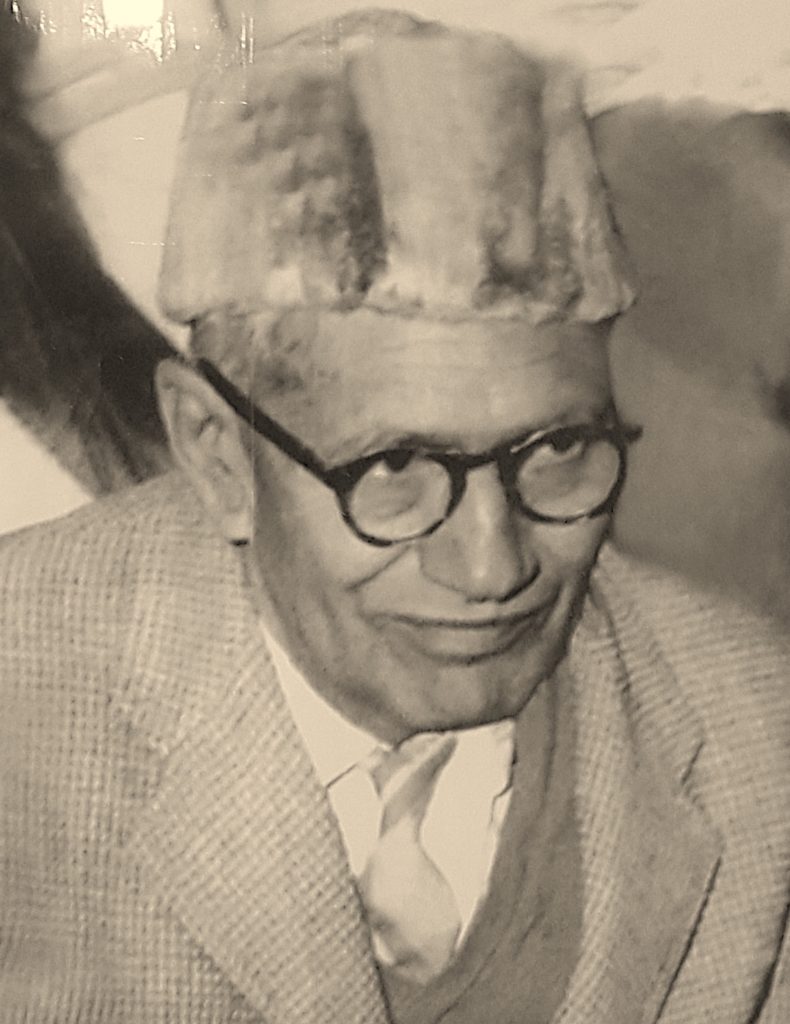

In the very first year in Lahore, I came across Chowla. He taught our class. He had something wrong with his teeth. He always pronounced `s’ as `sh’, so many students used to make fun of him. But he was otherwise of the very highest calibre in mathematics. He was very presentable, and had also been to Cambridge, earning his PhD under the guidance of J.E. Littlewood. We didn’t know much about him initially, but he would come to the class without a sense of preparation as to what exactly he was going to do. He would start something, and start to think there right before you, and also make you think along with him.

Very spontaneous. And he carried you along in the process.

RPB: We had excellent teachers, and all of them taught us different subjects. But, Chowla was the most outstanding one. Our teachers identified three of us. The friend I am talking about–-Jagdish Luther–-and then Mahendra Raj, and I. Somehow within a very short time, they identified the three of us as being mathematically kind of ahead of the others. Luther was roll number 4, I was 5 and Mahendra was roll number 69. So, when any problem was given, the teachers would say, “Roll numbers 4, 5, 69–-one of you come and do it.” Chowla also had this other habit: After the examinations, he would take my paper, nominally award me full marks right there, and then check the paper for where I had actually lost marks. That is the sort of encouragement we got from him.

Was this your first ever encounter with Chowla as a teacher?

RPB: Yes. I have since then had great, and long interactions with Chowla. I didn’t realise in the beginning that he was so great. I saw him only as a teacher who encouraged you to think sharp, and who also thought well of you. Many people found his classes difficult to follow because of the slightly odd pronunciation. But everyone felt inspired because he made you think on the spot. He would write on the board and rub off the chalk, and then later absent-mindedly put his hand on his face, ending up having chalk marks all over. It was always fun, and always inspiring. Here was somebody who was so committed to his subject, that he just didn’t mind, or even bother about having chalk on his face. He was well dressed too, but he didn’t bother about other things. He was kind of lost in his teaching. Mathematics was his life, and he was always very much involved and engaged in doing it. Whether it was simple mathematics, or difficult mathematics.

So he was the one who sort of made the strongest impression on you?

RPB: Yes, he was the biggest impression.

Jagdish Luther, Mahendra Raj and I have been friends since 1939. After we got married, our wives became good friends, our families got to know each other too. They are still my closest friends. Jagdish Luther joined the Civil Services, and went on to become the Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. Mahendra Raj went into engineering, and he is one of the best structural engineers in the country, and has made great contributions.

Did he too work in India?

RPB: For some time in America, but mostly in India. The first high-rise building in Bombay–-Usha Kiran–-was designed by him. He has even worked with the famous architect, Le Corbusier. So the three of us have done pretty well.

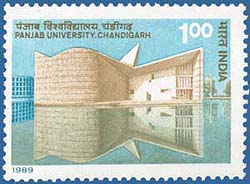

You mentioned Le Corbusier. Isn’t he the one who designed the city of Chandigarh?

RPB: Yes, and it was Pandit Nehru’s initiative. See, when we lost Lahore to Pakistan, he wanted to give us another town equal to Lahore, and so he commissioned the best designer in the world. So the three of us have been together for almost 80 years now. Our families are also one large, close-knit group together.

Are they both in Chandigarh now?

RPB: They are both in Delhi now.

So, coming back, we three went to Government College, Lahore, together. I did well in the house examinations and after two years, we had the Intermediate examination. People who took all science courses were called FSc, and people who took less of the sciences were called FA. In the examination, I stood first in the university in FA, although the Intermediate exam had three students with more marks than me. I had 537 marks, and the toppers in FSc had 543, 540 and 538.

Then in B.A., apart from studying for the B.A. degree, you could get an honours degree in a certain subject, but only after studying and clearing some additional papers. So Mahendra and I, both had honours in Mathematics.

Your memory is remarkable. You were quite ahead in mathematics, but did you also explore any other subjects like physics, or perhaps something else that also interested you?

RPB: No. You see, during my Intermediate days, I had taken up Mathematics, Physics, Sanskrit, and English of course, and the optional subject Hindi. I stood first in the college in all examinations, in total. Overall, let us say, I was good at tackling examinations.

And you always enjoyed it?

RPB: I don’t know whether I enjoyed it or not. I just did it. The Sanskrit course was very strange. We did the Sanskrit verses in English. The surprise was that the basic medium of instruction, even for Sanskrit, was English. Therefore, we would read in Sanskrit, but then immediately translate everything into English, and so forth. So, I completely forgot Sanskrit. Physics was very elementary, and I did pretty well.

What motivated you to take Sanskrit? Did you want to learn the language?

RPB: I come from a DAV institution. Hindi, Sanskrit, Hinduism, nationalism–-those sorts of things were prevalent at that time. In any case, I was also told that if one took the IAS examination, one might actually find this subject to be of real use.

In my B.A., I opted for Mathematics, Hindi and English, and honours in Mathematics. I started my B.A. in 1941 and completed it in 1943. I stood first in the university in B.A., and I stood first in honours too. I also had more marks than anybody had gotten before. It was recognised by that time that I was good at mathematics–-at least, if not good at original mathematics, good at whatever was part of the Mathematics syllabus.

And were you also convinced that mathematics was what you wanted to do?

RPB: No. Till then it was only the Civil Services. I had always been a middle-class guy, and we were a family that was certainly lower middle-class. The one strong ambition my parents nurtured for me was that I should make it to the higher middle-class/strata of society.

You said you are the third among your siblings. You had two sisters before you. Do you have any other siblings?

RPB: Yes. I had three sisters after me, and a brother, who is 10 years younger to me. All seven of us survived some tough times. You see, five sisters and two brothers, and the family quite expectedly thought that I could probably help them.

So in B.A., I stood first in both the university exam and in the honours course. This was again at Government College Lahore, Panjab University. After that, I joined the M.A. program. Obviously, English or Mathematics were the subjects to choose from. I took Mathematics. But in the M.A. course, teaching was done on an inter-college basis.

Meaning?

RPB: Up to B.A., the college that you were enrolled in was the primary affiliation. But for the M.A. course, all affiliated colleges would pull their collective resources together, and would share the teaching. There was one Professor of Mathematics in the university, C.V.H. Rao, a geometer, and he was the coordinator.

Did you have to go to different colleges for attending various courses?

RPB: The university had two rooms. So, either the teacher would come to the university, or we would go to the colleges, depending on mutual conveniences. We were about 50 students. My M.A. went off pretty well. The M.A. examination was held after two years. There was no other house examination, but there was homework. I heard feedback that the teachers thought very well of me. The first examination that we took was in April 1945. And the first paper was Analysis. The paper was very unusual, and most of us did not do well, but I still managed to score 80 marks.

80 out of 100?

RPB: Yes. Then we took the second examination, Geometry. Before it was time for the third examination, most students felt that they were going to fail, and they all came rushing to me, saying: “Let’s do something.” We decided to go on a strike. After taking two papers, I too joined them, which was rather unusual, because I myself was doing quite well, actually.

You did not have to go on a strike, but …

RPB: Yes, I didn’t have to. But I still joined the strike, and surprisingly, our teachers were supportive. They told us that we were doing something wrong, but they still stood for us, and then the university finally came around and saw our point. Before that turn-around happened, we wrote two more papers. So, I took four papers out of the six and missed two. Some people took five out of six. Then the university finally relented, and said that they would hold another examination in September. In any case, our teachers had convinced the decision-makers that the paper was indeed unfair.

So they conducted a re-examination?

RPB: They said that they would conduct an alternative examination in September, but that they would place on offer the results of the present examination too. One would be given a choice of whether one wanted to choose this set of marks, or the other one. The university rule was that you may have failed in a paper, but if your total score was more than that required for ‘Second Class’, then you could pass, and that you would be given a ‘Pass Class’. Since we had taken four or five papers, many of us would have anyway obtained more than 300 marks. So, I was called by the Registrar and told that I was getting the First Class. That meant more than 390 marks. “Why do you want to take another examination,” he asked me. I said that 390 was way smaller than a potential 600. And I opted for the new examination. In Mathematics papers, there used to be 12 questions. Six fully correct answers already gave you full marks, and you were allowed to attempt up to nine questions only. Because of my speed, I was able to attempt seven or eight of the twelve. As a result, I got full marks, 600 out of 600. Nobody had reached this mark before. The best before me was 579 by R.K. Talwar, who later went on to become the Chairman of the State Bank of India.

You beat all the records, and your decision to take the alternative exam paid off.

RPB: Yes, and it also established me as somebody to be noted. Most of my peers know this fact about me. They don’t know or care what I did much later, but they know that I got 600 marks out of 600, in my M.A. That is something people mention even now. “Oh, you are that fellow.” That sort of thing.

This was in Master’s, right? And, 600 out of 600 would be an unbeatable record.

RPB: Somehow, it has not been beaten, but one of the things is that the system has changed. That system continued for some time, but it has changed since.

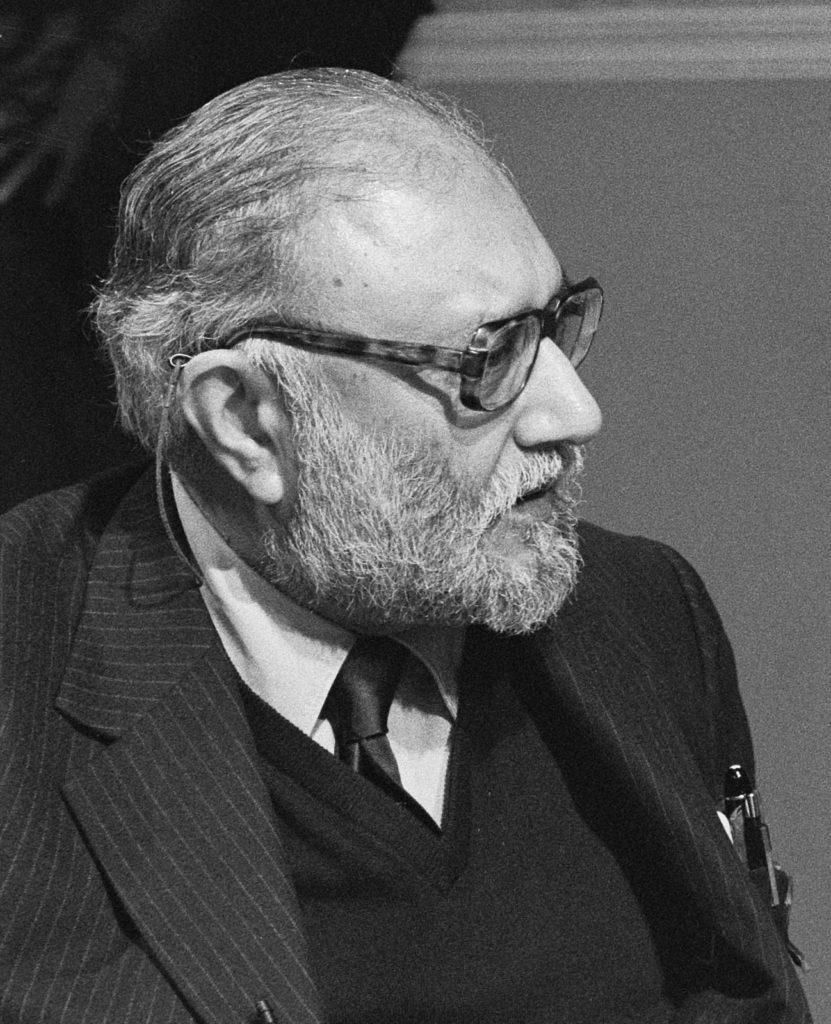

Abdus Salam, who later got the Nobel Prize in Physics, was one year younger than me. He came to college for the B.A. course, and was there for his M.A. too. We were both from lower middle-class families that really couldn’t afford to buy books. So, we borrowed books from the library. The two of us were very close. Abdus Salam got 573 in his Master’s, the year after me. The system was the same for him also.

Did he also do his M.A. in Mathematics?

RPB: Yes, he did his Master’s in Mathematics. Then he also did the Cambridge Tripos in Mathematics. After that, he became a mathematical physicist. He had done well in all the examinations. He had done better than me all through, in matriculation, Intermediate, and B.A. Though I too had stood first, he had much better scores than mine, in his own batch. M.A. was the only time when I did better than him.

Later, in Cambridge, he became a Fellow of my college in 1951, and I became a Fellow in 1952. I competed in ‘51, but did not make it. In ‘52, I made it. He was ahead of me there. He was my senior in Cambridge, because he had gone there earlier. So we knew each other for four years in Lahore, and then we were together again in Cambridge.

You moved from Lahore in 1946?

RPB: Yes. What happened was that in 1945, examinations were held in September. Then my results were declared in February 1946.

Was Sarvadaman Chowla your teacher during Master’s, too?

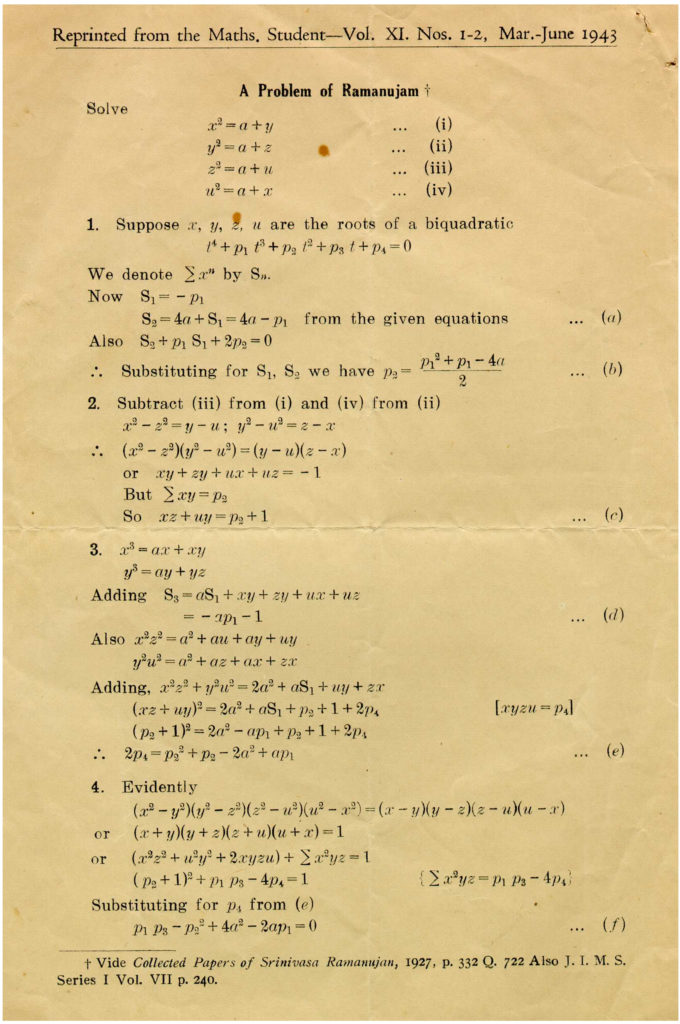

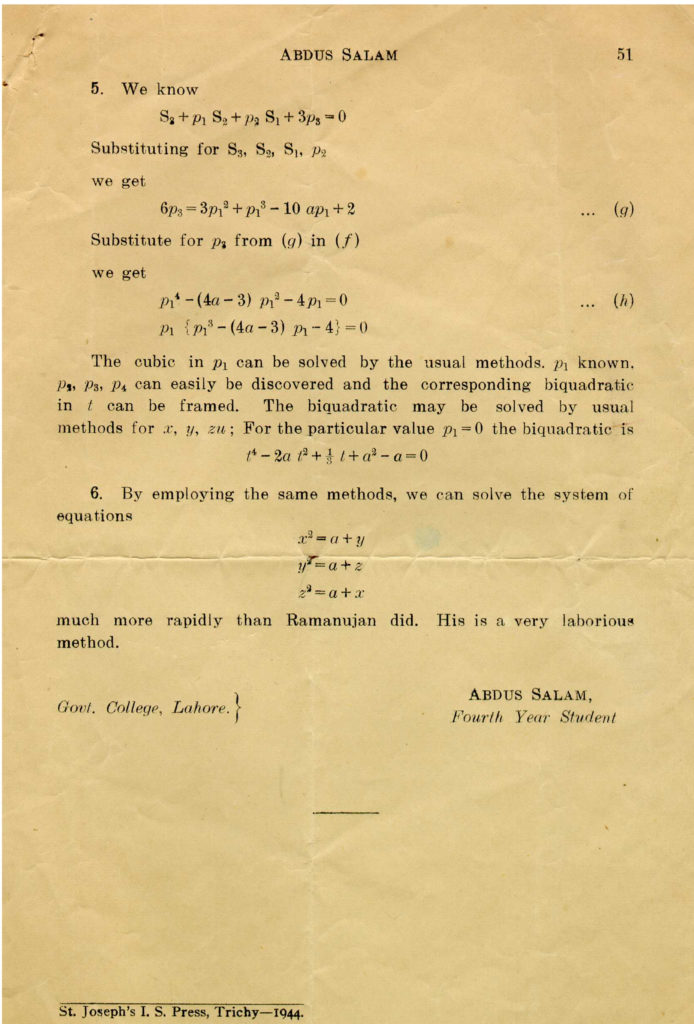

RPB: All the time. For six full years, and he was a sort of a big role model for some of us. Surely, for Abdus Salam too, for instance. In one of his classes Chowla wrote down an equation proved by Ramanujan. Salam worked on that for a week or so, and brought a solution to Chowla. His solution was simpler than the one by the number theorists. He was still a B.A. student at the time. They then sent the paper to Mathematics Student. It appeared there.1 This must have been in 1943. This for you, is the “Chowla influence”. Chowla sometimes would suggest some unsolved problems and simply see what happens. Nothing happened, of course–-most of the time, at least!

But something potentially interesting could actually happen, is how he may have felt. And if there were students like Salam, who did get a solution better than Ramanujan’s, he was justified too.

RPB: Absolutely. The Indian Civil Service [ICS] was no longer there, but some alternative to it started off. At the time when we did our M.A., there was this British delegation that came up with a formula for the horrendous Partition of India, with the Muslim majority in the other part. In the Civil Services, and in the All India Services, there were some things common to everybody. Administration of the Muslim majority areas would be different from that of the others, but an examination was conducted for other services. For example, Jagdish Luther took that examination and could not go on to the IAS because he came from Punjab. But Revenue Service and Customs Service jobs were available for him. He joined the Revenue Service. I was not of sufficient age to take the examination, and so I had to look for something else.

Was there some kind of age limit?

RPB: You had to be above 21 to take the examination, and below a certain age, 27. So that year, I could not take the examination. If I had been a year older, then I might have taken that examination. In any case, I had to look for a job.

Now, we took the M.A. examination in September. At that point I knew my result, but it was not declared due to technical reasons. It had to be approved by some authority.

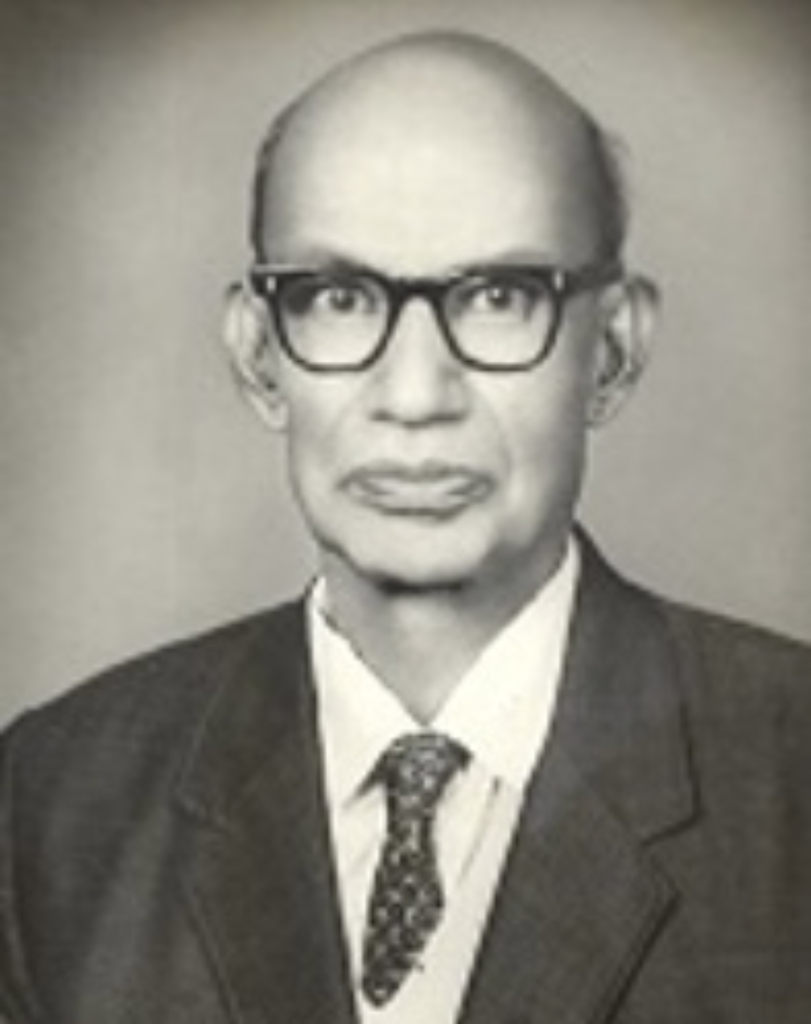

In 1945, Hansraj Gupta was at the Government College of Hoshiarpur. One of his colleagues went on leave to fight an election in December of 1945. The classes were on, and so they needed an extra teacher. Hansraj Gupta contacted Chowla to find somebody to fill the gap. Chowla asked me to go and see Hansraj Gupta: “See what the place is like, and what they do.” So I went with his letter to Hansraj Gupta.

Chowla and I published a total of 15 papers, starting from April 1946 to February `47

He gave you a letter of recommendation?

RPB: Something like that. There were no telephones at that time, you see. So Hansraj Gupta took me to the Principal who was also a mathematics teacher. The Principal said, “You start teaching tomorrow.” I said I was yet to even see the place. I didn’t even have extra clean clothes to change into. I asked, “I don’t have a place to live. Hoshiarpur is a small place. There is no hotel or guest house here. How can I start teaching tomorrow?” Hansraj Gupta had a family with three daughters and a son, and had a small house. He said he could put an extra bed in his room. At that time I was very thin. “You can even wear my shirts,” he told me. “Your suit is alright, and you can start teaching.”

You had just gone there to see the place and explore things, but then …

RPB: Yes, I had gone simply to see the place, and see whether they wanted me at all or not. At the time, I didn’t even have my degree. My degree results had yet not even been declared. So I started teaching the very next day in the Government College at Hoshiarpur.

For three months, I was there. After a week, my mother came over, and we started looking for a place to live but couldn’t really settle down to finding a suitable place. There was a small hostel, but the family I was staying with would simply not approve, and made it impossible for me to either move out, or even eat out. I was used to having tea quite often. My mother used to, too. But my hosts didn’t. Tea drinking started in their house because of me. Many changes took place because of me. They didn’t know me at all, initially. I was just a stranger, but they were such extraordinarily nice people. I was there for three months and it was as if they were not doing me a favour, but I was doing them a favour.

This was their commitment to teaching, and the fact that you actually filled the gap.

RPB: They were very decent people. Otherwise, who would entertain a stranger, with young girls in the house? Lahore, where I came from, was a more fashionable town, and one could not really be very sure of the kind of background that I actually came from. Yet, they simply trusted me, and opened their doors to me.

I was there for three months. Then the teacher whose position I had been filling in came back, and I went back to Lahore. In the meantime my result had been declared and Chowla asked me. “Would you like to work with me?” I said, “Nothing better.” Panjab University had two research positions. One research position was vacant, but it was not in mathematics.

So Chowla took me to the Dean, told him about my background, and said that I may be given the scholarship. The Dean said, “Young man, don’t suffer from hyper-intelligence. Go and prepare for the ICS.” But he still gave me the scholarship. So in March 1946, I started the job in Lahore. This was a research scholarship, working with Chowla. It was in reality no place for research scholars. There was nothing there, but Chowla still took me as his research scholar–-75 rupees per month, and we started.

Did they have any accommodation there?

RPB: No. My parents were living near Lahore, six miles from the college. I stayed at home, and then I realized that I also had a very poor background in mathematics. I had done well in my M.A., but we didn’t really learn much there. In number theory, for example, all we knew was some elementary number theory. I had not even heard of a matrix. I had not even heard of a group. At the time, in the syllabus that we had, analysis was alright, geometry was alright, but number theory was minimal. I had heard of a determinant, but nothing of a matrix. Things like that.

Chowla was a great mathematician, but for training young people, I don’t think he was ideally suited. He was not interested in telling you what to read. He was interested in doing things. So when I joined, he gave me Ramanujan’s paper, and said, “There is this tau function. Ramanujan has some congruence properties. See if you can do anything about it.”

So I looked at certain infinite series due to Ramanujan, which I now don’t remember exactly. Basically, by manipulating some associated polynomials, I could get some congruence relations, modulo two to the power five, and modulo five square. Chowla was quite excited. He took the two papers and sent them off to G.H. Hardy. Hardy put those two together, even edited them himself, and published them in the Journal of the London Mathematical Society, in 1946.

That was rather quick, I would imagine.

RPB: Then Hardy wrote back to Chowla quipping, “Thank you for sending your student’s papers. I have put them in a journal. But in future, you please edit your student’s papers yourself.”

This got us both excited, and we started working on the tau function. We examined higher powers of 2, higher powers of 3. We saw powers of 2, 3, 5, 7, 23 and 691. Chowla was a very prolific author. Some people may have thought that he was publishing far too soon, but his basic nature was to share. He was always willing to share. Even while working on a problem, he would share. If he knew he could do something about any problem he came across, he would gladly and willingly share. He was fond of sending out results even as they came out. It is not that he wanted publications, but it was in his essential nature to share.

So as a result, we wrote nine papers on the congruences of tau functions. Chowla and I didn’t meet every day. Sometimes, Chowla would write a note. I would be away six miles from college, with no telephones around. So when Chowla would write me a note, I used to meet him once a week or so. We usually would have lunch with his family. He would treat you as a member of the family. There was no office for Chowla or for me. It was in his house that we met, and we worked in his study. He would sometimes write me a note saying, “I can prove this. Can you?” So it was very exciting, and I used to meet him regularly.

Did he mean that in the sense that you may actually be able to get a different, or perhaps an even better proof than his own?

RPB: Right, absolutely right. Sometimes we had two different proofs of the same thing, and published both the proofs in the same paper. So we wrote a total of nine papers on the tau function and its congruences, between April 1946 and January ‘47.

Wow. That is prolific.

RPB: But if a slightly more sophisticated technical exposure was available to me then, I would have waited longer, and published them all in just one or two papers. But then Chowla had some other ideas too, and he would talk to me about those as well. One or two papers from that period involved some calculations. Eventually, we published a total of 15 papers in that period, starting from April 1946 to February ‘47, and it was hugely exciting.

You said that a couple of them were published in the Journal of the LMS. Where else did you send your papers?

RPB: Oh, we published them all over the place. Four of them were published in the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, two in the Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, two in the Journal of the London Mathematical Society, and seven in the publication brought out by the National Institute of Sciences. Now it is called IJPAM, but at that time it was called Proceedings of the National Institute of Sciences of India. So we published around 15 papers.

One such thing is a very elementary result, and for which we did get some attention. I think Vijayaraghavan wrote to Chowla on some facts related to the difference between sums of squares. By known results, you could get the order of the square root of x. I was in his office then, and Chowla told me, “Why don’t you look at it?” Well, one draws a circle to see what is the condition that one requires to get these lattice points, within these two circles. So Chowla gave me the broad idea, and went off. I sat in his study, and got a result by using very elementary methods. By a relatively straightforward construction, we proved the existence of a constant C such that for all x > 0, there is at least one integer between x and x + C(x^{1/4}). We published it in the Proceedings of the National Institute of Science of India.

It is a very elementary result, employing lengths of chords, and so on. In that paper, we mentioned that we believed that it was indeed a weak result, and that one should actually be able to obtain a much better result. And it turns out that Paul Erdös, John Littlewood, Louis Mordell, Harold Davenport and Paul Turan, all looked at that problem, and yet none of them has been able to improve on it. That elementary result is known even today because of the challenge, “How do you improve on this very simple idea?” That was one of the exciting things from that particular episode.

What you thought was a simple result has since then been extensively worked on, and yet has not been improved upon. Is this a fair assessment?

RPB:Yes. They all worked on it later, after we had. We had gotten this very simple-looking result, by using very simple methods. They said, “Well, this should be improved.” All that we had achieved by using simple methods is certainly liable to be improved upon, even drastically. But somehow, nobody has been able to do it so far. This has now become a challenge that Erdös has also mentioned. Littlewood too cites it as a challenge. So, that work has received a lot of attention.

Faqir Chand Auluck, who had done some work on Waring’s problem and partitions with Chowla, had been appointed to a Lectureship in Delhi University in the Physics department. Auluck and Daulat Singh Kothari did a lot of work using mathematics of partitions, and in statistical mechanics.

Then, Auluck got an INSA [Indian National Science Academy; formerly, the National Institute of Sciences of India] Senior Research Fellowship which, at that time, was a Reader’s level position. This was for three years, which meant that when Auluck took that up, they would need a substitute for the position he held at Delhi University.

Kothari had been secretary of the National Institute of Sciences of India, and also was an editor, possibly. He had seen all these papers that Chowla and I had written. Due to the alphabetical order of authors, as usually followed in mathematics papers, Bambah’s name appeared first. It thus became well-known as the Bambah and Chowla papers. Many people got to know of me because of those papers. So these people in Delhi also must have heard about me, and Kothari must have expressed an interest to hire me to Auluck, who in turn duly conveyed it to Chowla.

Back in Lahore, Chowla was like family to me by that time, and so I would go to his house often. Later when Chowla went to Delhi, Kothari wrote to him saying that since Auluck was going on leave, they had a position there. “We can have Bambah fill that position?” So without any application, I went there. It was now 1947.

Was it still pre-independence then?

RPB: Yes. But a lot of disturbance had already begun to take place. Riots were taking place, and a lot of unsteadiness was clearly evident. Even before this in Lahore, and soon after my M.A., when I wanted a job in the government, I was told that no Hindu could get a job in the government then. They were reserved for Muslims alone, and so there was, for me anyway, no prospect of a job [in Lahore]. I wasn’t really keen on leaving Lahore and Chowla, but it was an opportunity to move to a better situation. At that time though, we were not really thinking about moving, but we were all scared.

Then the Science Congress took place in Delhi, in January. We went to this Science Congress, and I happened to look at the syllabus of the Physics course that I was soon going to teach. I had never learnt any of those things. “How would I teach?,” I asked Professor Auluck, and he took me to Kothari. Kothari said: “Look, I have seen your credentials. We know you will be able to teach these things. If you have any difficulties, what are we here for, then? Auluck and I will be around, and we can discuss these topics with you if you don’t understand them now; and then with time, you can surely teach them all by yourself. But, I don’t think you will need us.” It is basically their attitude and trust that made it work. They were visionaries, they were not bound by stifling rules, and were essentially trying to do things by being open-minded.

So on 1 February 1947, I joined Delhi University; I stayed in the hostel. From 75 rupees a month, I had moved to a job with a 250 rupees monthly salary.

This was perhaps one concrete solution under the circumstances, to help yourself out of the situation.

RPB: I was able to send money home. I was staying in the hostel, and had friends around. At that time, Delhi University had a very enlightened Vice-Chancellor in Sir Maurice Gwyer, who was also once the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India. His ambition was to expand Delhi University, academically. Delhi University did expand, and very well too.

So we worked there, and it was fun. Then 15 August 1947 arrived, and we were finally independent. With Independence came the horrors of Partition. With the Partition, the massacres started, and I had no contact with my family.

They were in Lahore, I suppose. And you were in Delhi, with no way to reach them. That must have been quite a traumatic period.

RPB: Yeah, very traumatic, because I didn’t know what was happening.

There were no phones. Then, a miracle happened. It was in September that the whole family turned up in Delhi, including my parents, my sisters and brother. They temporarily stayed at a friend’s house in Delhi.

So they did come to Delhi. Somehow they all made it!

RPB: They made it with great difficulty. There was something else there too, but I won’t go into the details.

As usual, I met Professor Kothari and they allotted me a house on the campus. So my family and I moved to this house. My father got his job at the railway station. A large number of people—acquaintances, friends, relations and so on—came and stayed in our house for various periods. At that time, that was how things were—all the houses were open to anybody who came in.

Open to anybody because it was a time of great trauma. It is really incredible how people come together in times of uncertainty. Let me backtrack just a little bit. You said they moved to India with great difficulty, but also that it was not a truly desperate and potentially life-threatening situation when they moved to Delhi from Lahore.

RPB: Yes. In the sense that at one stage, when they came to the border, the Pakistani people had moved on even further, but the Indian people had not yet taken control of certain areas. My father and another person from the railways took charge of a train and moved it to the Indian border. They were all in it together.

Anyway, the university gave me a house, and people stayed there for a long time. Earlier, I had applied for the `1851 Exhibition Scholarship’.

‘Exhibition Scholarship’! That’s to go to Cambridge, isn’t that so?

RPB: You see, it could be used anywhere in England. It was a scholarship given to various British dominions. We were surely not among the dominions, but India still had one of these scholarships, and I had applied for it at the suggestion of Kothari and Auluck.

And what was the scholarship for?

RPB: For research in England.

In Lahore, when you worked with Sarvadaman Chowla, that was a research scholarship. You wrote so many papers, couldn’t you have converted that into a PhD?

RPB: I moved away from there within just a year. First, Kothari and Auluck thought that I would join Auluck, but for some reason or the other, my true interest was not really in physics and they didn’t push me. So I applied for the scholarship. I eventually got it, but now the problem was that my family was staying in the university house. I myself had only a temporary position in the university. If I took the scholarship and moved out of the campus, I would have had to inevitably give up the university quarters too, and all the attendant benefits that came along with it—everything.

It was very difficult. Then, again Kothari talked to Sir Maurice who said: “Tell the young man not to give up this opportunity. We will take care of his family.” Even after my resignation, my family had to be still taken care of. Sir Maurice came back saying that they had newly appointed a few lecturers. Further still, he went on to say, “Dr. Mathur in Chemistry will need a house. We could give Mathur a house, on the condition that half of the house could be occupied by Bambah’s family.”

The house was big enough to accommodate two families perhaps. This was a welcome partition!

RPB: Yes. On the condition that my parents were to be in one half of the house, and the Mathurs in the other half. The Mathurs were very nice people.

So I went off, reasonably at peace, to England. While I was in England, the house was pulled down and the Mathurs were allotted a new house, but with no extra room there. And, so the same nagging question arose all over again: “What will my family do?”. I wasn’t around in Delhi when all this happened. But people again came to help us, saying, “We have so many barracks on this campus. This campus was taken over by the university from the old Vice-Regal. So, let us give them four or five rooms in a barrack.” So, four rooms were given to my family. Then my father got transferred to Ghaziabad as Chief Yard Master, and they finally had a big railway house, all unto themselves. But we must note the generosity of these people who helped us when we were really in need.

Exactly. In such times when there is so much turmoil around, I feel, people coming together and lending a helping hand is so reassuring!

RPB: Yes. Also receiving help from people with whom I really had not kept up at all. Yet, they were glad to help my family when I was not there, and also took good care of them. It was a great experience.

Then I landed in Cambridge. Now, you see, the problem was that my background in mathematics was indeed very poor.

What exactly do you mean by a poor background? You always did well.

RPB:No! The point was that we had not done any of the topology or algebra courses. Even the idea of a Lebesgue measure, I didn’t really understand—things like that. It was kind of a fairly modest background.

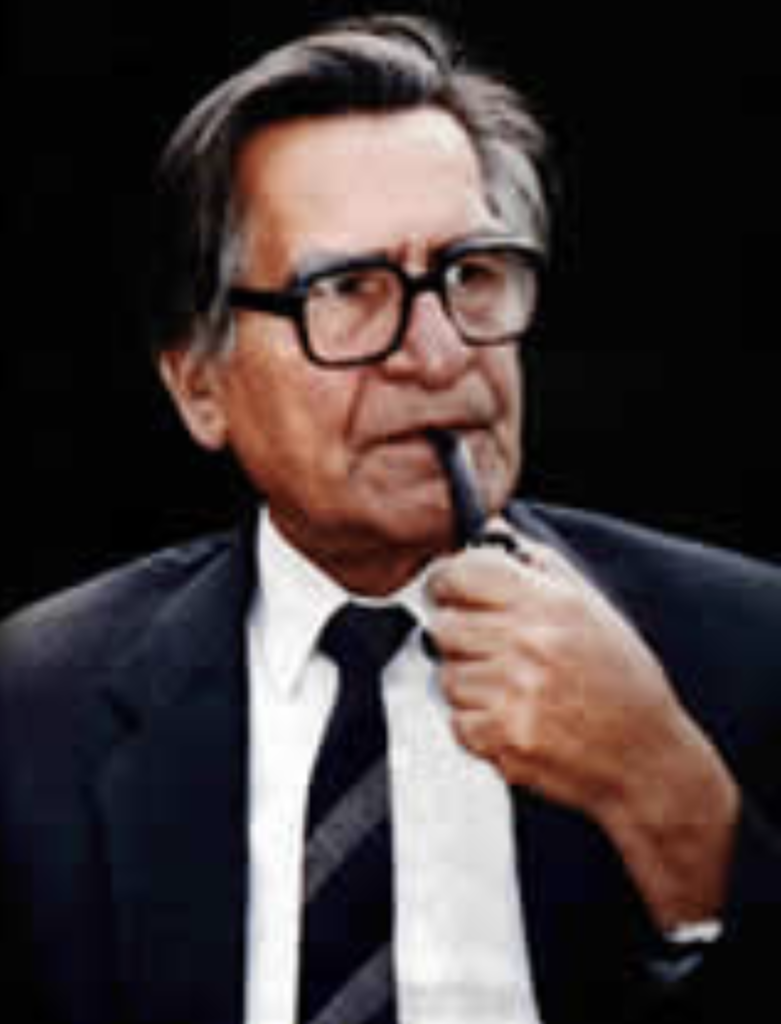

But instead of learning mathematics, which is what I should have ideally done, I was scared that if I didn’t produce good work, my scholarship would stop. Every year, for three years, I had to submit a report. I was scared of the prospect of losing my scholarship, and so I talked to Louis J. Mordell to suggest to me a problem to work on. He simply told me to attend some lectures instead.

By the time I went to Cambridge University, and to meet Mordell, Chowla had already written to him to take me on as a student. When I went to see Mordell, he said: “Why don’t you move to a college?”. But I wasn’t at all sure that they would admit me. He said, “I thought you didn’t have the money and that’s why; but you do have enough money.” So he got me to St. John’s College. I started working, and then I looked at my admission which said that I was admitted for research, but without ever mentioning any degree that I would earn after graduating. I told Mordell that this admission letter didn’t say anything about my degree. He said, “Why do you bother? Just do your work. If you do your work well enough, we will take care of the rest.” So, I simply followed his suggestion.

Things were liberal, you could say.

RPB: That was their maturity. So, I would go to Mordell now and then, pleading, “Sir, please give me a problem.” He always simply would say “Go attend some classes.” So, I attended some more classes.

What classes did you attend? Hardy, Littlewood must have all been around then?

RPB: Hardy had died. J.E. Littlewood was there. Robert Rankin, Louis Mordell, Albert Ingham—these are the people who lectured. Philip Hall, too. I went to linear algebra lectures, for instance. Attending lectures without taking any examination was a wholly different thing from taking examinations. I got exposed to a lot of mathematics but without preparing for, or actually writing, an examination. I didn’t know any topology. I didn’t know what a compact space meant. I was all along also scared that my scholarship would get over after a year because I had not gotten any new results to show. I thought they would simply say, “Alright, go back,” and I would have no job back home in India either. I had nothing. And this got me very nervous.

Then, seeing my sheer desperation, one day Mordell said, “I did this thing for symmetric sets, and then I did some work for non-symmetric, non-convex sets with some attendant symmetry. Why don’t you look at it for the case of hexagonal symmetry?”. So, finally glad to be assigned with a problem to work on, I simply disappeared and started working on it.

One day when Mordell saw me, he said: “I was looking for you to tell you that you won’t be able to do it. Don’t do it.” The reason for his particular advice was that he had spent nearly an entire year on that particular extension. Being the first to work on that problem, he had to find every single step by himself. But, for me, I had a ready model before me, so I followed the model, and by April I had actually succeeded. Also by then, he seemed as though he himself had given up working on it. When I went to him with the solution and told him that I had actually done it, he said, “I don’t believe you.” I then said that he might want to have a look at it. John W.S. Cassels, who was my contemporary but slightly senior, and who was also one of Mordell’s own students, was there. Mordell said, “Give it to Cassels.”

Because he may have felt that there could be something?

RPB: Cassels looked at it, and said that it was fine. Then Mordell suggested that I would spend one hour with him every week. We went into the minute details, step by step into the whole thing, and checked it. Because of the fact that he had worked for a year on his own problem, he had this impression that I had done something very unusual. This helped me greatly because I thought that Mordell now thought of me as somebody quite competent. Finally, he declared that everything was alright. “It is only one year since you came here. Normally the degree duration is for three years. You can get it in two years by also citing your own work done in India; but in less than two years, you can not submit your thesis.” So, I worked on some other things related to these aspects.

It must have been a huge relief since you didn’t have to worry any longer about the scholarship, and the degree.

RPB: Yes. By the end of two years, I completed my thesis. And then Mordell said: “Now you can submit the thesis.” My examiners were Davenport and Mordell, and the viva was very favourable. Before I submitted my thesis, Mordell asked: “How many copies of your thesis are you making?” I said two—one for myself that I want to keep, and one for the university publication. He asked me to make five copies. I said, “But, why sir?”. He said, “Don’t you want to compete for the Fellowship?” This was for the Fellowship of St. John’s College. So I made five copies. Then came the publication. I had this long paper, nearly about 80 pages long. I asked if we should make it into smaller, easier to read parts. He said, “Don’t you want people to see your work in full?” I said, “But who will publish it?” He said, “That’s my responsibility.”

An 80-page long paper meant that it must have had a lot of calculations!

RPB: No. It was more of a geometrical nature. And Mordell said, “Send it to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.” I had three other papers. Two of them went to Acta Mathematica, and one went to Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. Davenport was my thesis examiner. So, everything was working fine.

Professor Bambah, by saying “competing for Fellowship”, what did he mean?

RPB: Cambridge has colleges affiliated to the university. The faculty of these colleges are called Fellows. Most of them are also simultaneously Fellows of the university too, while a few of them are not. People from Cambridge and Oxford can compete for this Fellowship which gives them three years of free time. The tradition was that these Fellows eventually stayed on for as long as they wanted in the colleges. Mostly, once you are a Fellow, you are a Fellow for life. But in my case, it was only for three years.

So, I got this Fellowship and everything worked fine. Two years of work, and I had my Ph.D. too. Papers were sent away for publication. The question was that since I had a scholarship for another year, what do I do in the third year? I decided to work with Davenport.

In the meantime, when this paper went to the Royal Society, Kurt Mahler was a referee. He remarked, “You are using Cartesian coordinates. Why don’t you choose more appropriate coordinates?” So, I got the paper back. I worked on his suggestion, and from 80 typed pages, it came down to 60 pages.

At that time, Claude Ambrose Rogers had done some work on packings and coverings. Davenport suggested that I might look at some of these things. This was one thing that Davenport suggested that I actually ended up doing. But both Davenport and Rogers thought that I had assumed a certain symmetrical structure, which was not really justified.

In the same `hexagonal symmetry’ paper?

RPB: No. This was in another paper on coverings that Davenport had worked hard on.

I myself had gotten some approximate results in dimension 3, and he had some for dimensions 16 or so, without assuming any symmetry. But then Rogers and I almost simultaneously discovered that we didn’t really need a justification after all, and that what I had claimed was indeed correct. I told Davenport about this. Then he said, “Alright, you publish it.” I said that I would like him to join as well, and so Davenport and I wrote a joint paper. That was the first time we started up on these things, and much better results appeared later. But the first result we had showed that a covering by spheres has a density greater than one. More precisely, we showed that the density \vartheta of any covering of n-dimensional space by equal spheres (whose centres form a lattice) satisfies the following expression: \vartheta > (4/3 - \varepsilon_k) where \varepsilon_k \rightarrow 0 as k \rightarrow \infty.

I wanted to look at coverings, too. Rogers had done some work for packings in two dimensions that could not be improved upon, and he said, “Why don’t we look at their coverings?”. So Rogers and I worked hard on it and we got some results. We proved what we wanted to prove. In the meantime, Paul Erdös, who came there, informed us that Fejes Toth had also done it. We were a bit disappointed because our work was more complicated than theirs. Fejes Toth was a big discrete geometer. We were disappointed but in any case we had learnt something.

Their work encompassed your work. Is that right?

RPB: Yes. Fejes Toth was working in discrete geometry for a long time. We were just then coming to discrete geometry via number theory. Fejes Toth had used something which was still unproven in this paper. Rogers and I worked on it, proving the particular part and also introduced a new concept. This concept has now been found to be quite useful. We published the paper.

Is this concept known by any particular name?

RPB: No, we said that they are crossing and uncrossing. I mean, how do they cross—this sort of thing. That paper has been appreciated very much, and has had a great impact. We published it in JLMS. The paper with Davenport was also published in JLMS.

This is all during your postdoc years, for three years.

RPB: This was in the third year. A lot of work was being done at that time on packings and coverings, and I was looking at something which I thought would be an improvement on the known results. Klaus Roth was there at that time. One day we were in the lounge having lunch. He asked me what I was working on. I told him what I was working on, and that I needed something which I couldn’t quite really get a good hold of. He said, “Why don’t you try with simpler sets like polygons and see whether it works?”. So, I tried with polygons and things worked. And we got the result. Then I generalised it to the case of more general convex sets.

Klaus Roth was your contemporary. Was he younger than you, or was he of the same age?

RPB: Same age, actually exactly a month younger to me. He was still not famous at that time!

He won the Fields Medal in 1958!

RPB: Yes, at the ICM held in Edinburgh. I asked Roth if he would like to share this paper with me. He agreed, and we wrote that paper together in 1951. We went to Davenport asking him to suggest a good place where we could publish it. He opined that if I were going back to India, then we should rather publish it in an Indian journal. We sent it to the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society. So, I had three papers in all from that time. One with Davenport, one with C.A. Rogers, and one with Roth. They were not great papers, but they were somewhat impactful.

When Mordell suggested to me that I compete for the Fellowship, I also told Abdus Salam about it. Salam said that even his advisor had suggested to him to compete for the same Fellowship. So in ‘51, we both competed. Five people were elected from all the subjects. Salam was elected, but I was not.

So your time in Cambridge also overlapped with that of Salam.

RPB: I got there in ‘48. Salam was already there. We were also in the same college in Cambridge. We dined together every single evening because dining there was compulsory for five days a week. All of us—and there were six to seven of us Indians—were used to dining together. Salam and I also used to go for long walks together, talking along in Punjabi, which both of us had in common.

Then Mordell wrote a letter to the Vice-Chancellor of Panjab University stating that I had missed the Fellowship by the skin of my teeth, and that if I continued to do some good work later, I might actually get it in the coming years. So, I came back to India in ‘51 with no job on hand. Professor Kothari had then become the Defence Advisor. He said, “I can take you into Defence.” I said that I didn’t want to go there.

Quite naturally so. You were so successful. Why would you want to change?

RPB: The job that I had, had already been converted. Auluck had become a Professor. At that time, Ashok Mitra got my previous position. Then Professors Chowla and Mordell both wrote to the Vice-Chancellor of Panjab University, Diwan Anant Kumar, mentioning that I was coming back to India, and that they both thought that it would be good for the university to have me. I went to meet him. He said [in Hindi], “Sadleirian ke Professor ne mujhe likhe hain. Main to tumhe Readership position create karaake de dunga. [The Sadleirian Professor had written to me. I will create a Readership position for you.]’’ There was only one post in the Department of Mathematics which had then not yet been filled. “Reader nam ka de dunga,” he said. I was happy. Then he took the proposal to the Syndicate. They said that back in Lahore, there was only one position. “Why do you want to have more than one position here?”. Things like that \ldots they were very narrow-minded.

And Panjab University was in Chandigarh at that time, right?

RPB: At that time it was still spread out. So my application was essentially turned down. I went to the Vice-Chancellor again. He said, “The Syndicate didn’t agree because someone opposed it, but you don’t have to worry. I will get it done.” Then Professor Kothari suggested that I try the fellowship that Auluck held at INSA, which paid Rs. 500 per month. So, I applied and got it for one year. Thus I started working in Delhi University as an INSA Research Fellow.

Davenport had suggested to me that now that I was working on coverings, and since this whole thing was still new, why don’t I look at coverings of 3-dimensional spheres—lattice coverings of 3-dimensional spheres. So, I was looking at it and was also corresponding with him. We had first thought that a certain lattice would provide the best covering. Then I wrote to him that I had a better covering than that. He was impressed. In any case, I worked hard on it and also worked on general theorems on coverings. Essentially, I solved the problem of the best lattice covering of the 3-dimensional spheres, which is also the work that has received the most attention.

In fact, better proofs came about much later. Eric Barnes, another student of Mordell, then took up the same problem. Barnes was a Fellow at Trinity, and he gave a better proof by using another method of reduction. I used Gauss reduction theory, but the more elementary way ahead was using the so-called Voronoi reduction, which Barnes used. Then another person gave a fairly geometrical proof, so there is now a total of three proofs available. My proof is the worst of the three, but was also the first.

But the result is the same. Proofs are different.

RPB: I used the wrong reduction whereas Barnes used the right reduction. L. Few, who was a student of Davenport, finally used ideas from geometry, and so things were working. I had two good papers, which I published in the Proceedings of the National Institute of Sciences because I was a research fellow there. This paper of mine is also among my most cited papers.

This was the result that I then informed Davenport about. After this, it got to be fairly well known that Bambah had done it. H.S.M. Coxeter wrote to me that he was also working on that problem. “Would you like to share it with me?,” he asked. I replied that I had already sent it for publication. You see, it was something that a lot of people had been interested in, but somehow I got the thing done. I was the first one to get there, although using the worst available method.

That also shows one’s ingenuity, I would imagine.

RPB: There is a lot of hard work that goes in, of course.

As a result of all this, St. John’s College sent me forms for the Fellowship again. I didn’t ask for it, but they sent it themselves. I filled in the forms and sent them back. Earlier on, thanks to Chowla’s generosity, between June and September of 1950, when I had finished up my Ph.D. at Cambridge but had yet not joined Davenport, I had been to Princeton and stayed at the Institute for Advanced Studies. There, I met Atle Selberg and others. When I got a message from Selberg that I should write to the Institute for a visiting membership, I wrote to the Institute also.

In April of 1952, I got a message from the Institute. Before that, I got elected to the Fellowship of St. John’s College. Salam sent me a cable where he said that he had been shouting from the rooftops that his friend, too, had made it.

Oh, amazing. I see.

RPB: I got a letter from Princeton accepting my request. In the meantime, Panjab University created a position and got me appointed as a Reader.

That’s an incredible year. Three big things happening at the same time. You were spoilt for choice, I suppose. Which one did you choose?

RPB: Yes, they happened together. I went to Diwan Saab, the Vice-Chancellor, and said that it was very kind of him. “I have these two opportunities in front of me, which are both great for a mathematician, and I won’t like to miss out on both.” He said [in Hindi], “Jaoge? Lekin kya wapas aaoge? [If you go, will you come back?]”. I said “Yes, sir.” Then he said, “Join the university at Hoshiarpur, and we will give you leave.” So, on the 1st of April ‘52, I joined the university at Hoshiarpur. There was no mathematics department there. The college had been taken over by the university and had become the University College. Courses had started in Physics, Chemistry, Zoology, and English. Mathematics had not even started. I became the Mathematics Reader there. Without an interview, I was simply appointed there, and Professor Hansraj Gupta and I were supposed to then jointly develop the mathematics department.

Was it already called the Panjab University?

RPB: No. It was simply called the University College. I went to join there and immediately applied for leave. I also gave a few lectures to some of the faculty. Professor Gupta was there. In August, I left for Cambridge first.

You accepted the Fellowship, right?

RPB: Yes. The rules there are that, in the first year, you get the honorarium stipend independent of whether you stay there or not. For the second and third years, you don’t get the honorarium if you don’t stay there, but you still get to keep the title of Fellow.

So, I went and accepted the Fellowship at St John’s College, Cambridge. I got my stipend and went to Princeton. At Princeton, somehow I regret that I didn’t make use of my opportunity there. The office allotted to me at the IAS was located very close to Selberg’s own office. He had to actually pass by my office to go to his own. He was also primarily responsible for my visiting membership there. But I didn’t interact with him. I was too busy trying to write my papers. And succumbing to the slogan ‘publications chahiye’ [`publications are a must’], I was stupid. I should have interacted with Selberg. I went to Emil Artin’s lectures but going to lectures is one thing, and learning is altogether something else. Not making use of my closeness with Selberg, which I ideally should have, is one of my regrets.

Is that regret something that you carry with you even now?

RPB: Yes. In the sense that I could have learnt a lot of things from him. Selberg was also known to be somebody who is a little aloof, but he was willing to help people, and I was right there. Before the year passed, Selberg asked me if I would like to stay another year. I said I would love to. So, I stayed back for another year, and after that he said that there was no more extension possible, but if I liked, he would look around for a job for me, in the U.S. I told him that my parents were in India. My sisters were still to get married, and that I had responsibilities back home. I simply could not stay. So after two years in Princeton, I came back to Cambridge and spent three months as a Fellow. Mordell was there, Paul Dirac was there. Salam was there, too. I was feeling at home, and on top of the world.

Exactly. Not many people get such an exceptional opportunity in life.

RPB: Mordell once told me during these days, “Now, you won’t call me Professor Mordell. You must call me Mordell. Later on, you will call me Joe. You have (1/90)th share in this College. If the College goes up tomorrow, you will get whatever is your part.” It was very lively and open.

The highlight was the high table after dinner meetings. During one such event, Mordell said, “When are you becoming a professor?”. I said that I didn’t know. He asked if there was an available position. I said, “There is a position vacant, but I won’t apply because Hansraj Gupta who is senior to me deserves it more.” He said, “Look, if he doesn’t get it, and if you don’t apply, and if somebody else comes and takes the position, how will you like it?”. I said, “I won’t like it.” Then he said, “You can apply for the position. But if your competition is only with Hansraj Gupta, then you withdraw your application right there.” I followed his advice. I sent in my application with a covering letter that if there is a choice between Dr. Gupta and me, my application may be considered as withdrawn.

I don’t know what exactly happened on this. Later, after I came back to India, I was told that Professor Gupta was appointed Professor, and I as a Reader. But I had been given six increments which took me to the top of the reader’s scale.

The day Professor Gupta joined, he and the Vice-Chancellor made it one of their top priorities to create another professorship in the department. They approached the UGC, and the UGC was also very responsive. In those days all the people who were in decision-making executive positions were very British-oriented. A Fellowship of a Cambridge college was a very unusual thing. I was either the sixth or the seventh Indian in the whole history of Cambridge University to get a Fellowship. Chandrasekhar and Ramanujan were there earlier, and I also had the advantage of having a British background. Therefore, UGC created another professor’s position.

In the meantime, I was in Hoshiarpur where we started classes and my teaching began. I taught three papers, Gupta two papers and one of Gupta’s assistants taught a paper. Six papers, in all.

All at once, and completely unexpectedly, I got a call from the University of Notre Dame. Telephones were not around at that time. I got the message that there would be a call in the evening for me at the local Post Office, and that I should be there. So I got there. Professor Arnold Ephraim Ross, who was chairman of the mathematics department at Notre Dame, told me: “Kurt Mahler, who is an expert in your area, is coming here as visiting professor, and is also giving a course. He wants somebody who can take notes of that course for writing a book later. It was suggested to us that you are the right person for the job. Would you like to come?’’. I said that I had to ask my Vice-Chancellor.

Which year was this?

RPB: This was in 1956. In the middle of all this, my marriage happened, on which I will come to a little later.

I contacted the Vice-Chancellor, Diwan Saab. This was the same Vice-Chancellor who had helped me all the time. I told him that I had gotten this message. “What should I reply?”. He said, “Take it.” I told the Notre Dame people that I will be happy to come. They said that they would give me the title of a “Visiting Associate Professor”.

In the meantime, the then Vice-Chancellor’s term came to an end, and a new Vice-Chancellor took charge. He was far-sighted too, but was a little more traditional than the previous one. So when I got this Notre Dame offer, I wanted to avail of some leave. He said, “I can’t give you leave because you have already availed so much of it earlier. Why do you want more?”. I said, “Sir, I have given this undertaking to those people based on the permission of the Vice-Chancellor. What do I do now?”. He was a botanist, and my father-in-law, by the way, was also a botanist. Finally, he said, “Jao [go], but I don’t like it.” That’s how I could go to Notre Dame.

So you could go. What was the then newly appointed Vice-Chancellor’s name?

RPB: A.C. Joshi. Diwan Saab built up the foundations, and Joshi built up the whole structure. We didn’t start off very well, but later on he became very fond of me. My father-in-law was senior to him, and he must have probably been his student or something. That’s the only time when my being someone’s relative has been used. Not by me, but by somebody else. In any case, I went to Notre Dame and spent a year there.

Were you married by then?

RPB: I will tell you. In 1954, when I came back from Cambridge, my to-be-wife had already received her MRCP [Membership of the Royal Colleges of Physicians, UK], and was also travelling back to India by the same boat. The boat took 17 days to travel from England to India. Those 17 days we were all free and moving together. Lots of people, even cricket stars like Polly Umrigar, Vijay Manjrekar and Vinoo Mankad were travelling along.

Cricketers?

RPB: Yes. They were also there. They were not all that rich at that time, so they were also travelling in the common class. We had fun.

Six or seven girls were also travelling with us, and she was one of them, and we spent some time together. There was a shore stop, and all of us also went out to town together. We did some shopping, and we liked each other’s company. By some chance, she later came to the place where I was staying, with something she had to give me. When she left, a friend of mine, Jagdish’s wife said, “Why don’t you marry this girl?”. I said I didn’t know. “She is from Orissa, and they were very high-class people, compared to our lot,” I told her. She said [in Hindi], “Wo uski marzi hain [That’s her decision].” I said, “Now the bus has left, and she is gone.” So things stopped there.

Then we came to Hoshiarpur, and I got a letter from her saying that she had taken some pictures on the boat. In those days, very few cameras were available. She had the films developed, and had sent me some pictures. I wrote back, thanking her for the pictures, also adding a line, “Will you marry me?”.

And she wrote back saying, “Yes”!

That is quite romantic, I would say!

RPB: Obviously we were interested in each other but we didn’t have the courage to go ahead. And somehow miraculously, things happened. You see, she was the daughter of a Vice-Chancellor, which I didn’t know at that time. She was a trained doctor, with an MRCP. She was from Orissa, and they were truly high-class people. Her family was very well known across India.

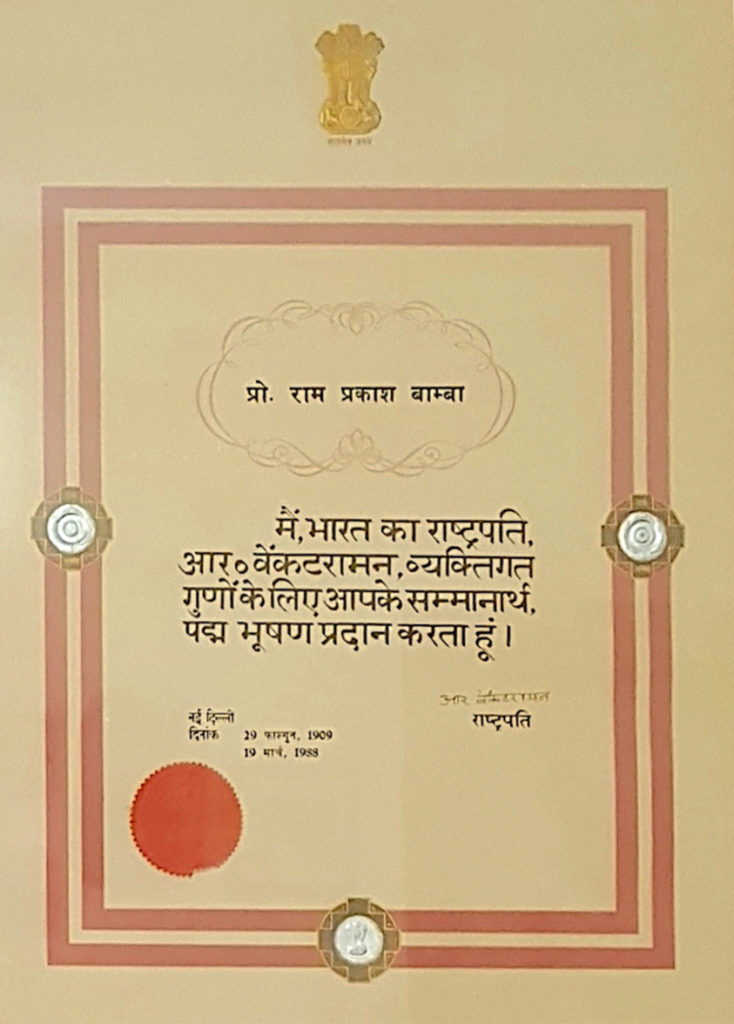

Whereas I was a comparative nobody, I guess. It was her generosity. Her father was the first Vice-Chancellor of Utkal University. He also had been the Pro Vice-Chancellor of Banaras Hindu University. He was a Fellow of all the major science academies. He also became President of the Indian Science Congress, was a Padma Bhushan, and had so many other accolades to boot.

Your wife’s name is Saudamini Parija. What is her father’s name?

RPB: Prana Krushna Parija.

At your home, was there no problem marrying someone from a different state?

RPB: No. My mother had very liberal views. My father was busy because of his job. My mother was really open-minded, and one thing she was very clear about was that her sons would not take any dowry, and also that her sons would not be forced to marry against their will.

Anyway, she sent me the photographs, but she hadn’t told her parents yet. This was November 1954. She said, “Your letter came to me on my birthday, and I thought what a present.”

Oh! Your letter went to her on her birthday, and that was not known to you.

RPB:20th November. I didn’t know, and letters took time reaching. She said she would talk to her parents. I wrote back to her saying that before she talked to her parents, she and they both needed to understand what she was in for. “I have a big family and many responsibilities towards my family,” I wrote. “I am only a reader and have other obligations. I thought you should know exactly what you are getting into.”

In the meantime, in January ‘55, I got elected to the Indian National Science Academy. Her father was also a Fellow of the same Academy. In January, she left the letter that I had written to her on her father’s desk. He saw that letter and told her: “You are grown up and independent. You must make your own decisions. Who am I to make decisions for you?”.

Then correspondences between us followed. She said she would come and see my place. Suddenly, she developed cold feet and didn’t come. Eventually by December ‘55, I was invited to Cuttack, to their place. I met the family and her brother, who was an IAS Officer, came over too, to meet me. He had been a student of St. Stephen’s in Delhi, and I had taught in the Delhi University Physics department. He had studied chemistry, but the chemistry people had to take a paper in mathematics. He himself had taken that paper in mathematics, and so I had been his teacher. He said that I talked too fast, and that he didn’t follow anything I taught at that time, that I had rushed through everything. I was certainly not his favourite teacher. In any case, he knew me from that time.

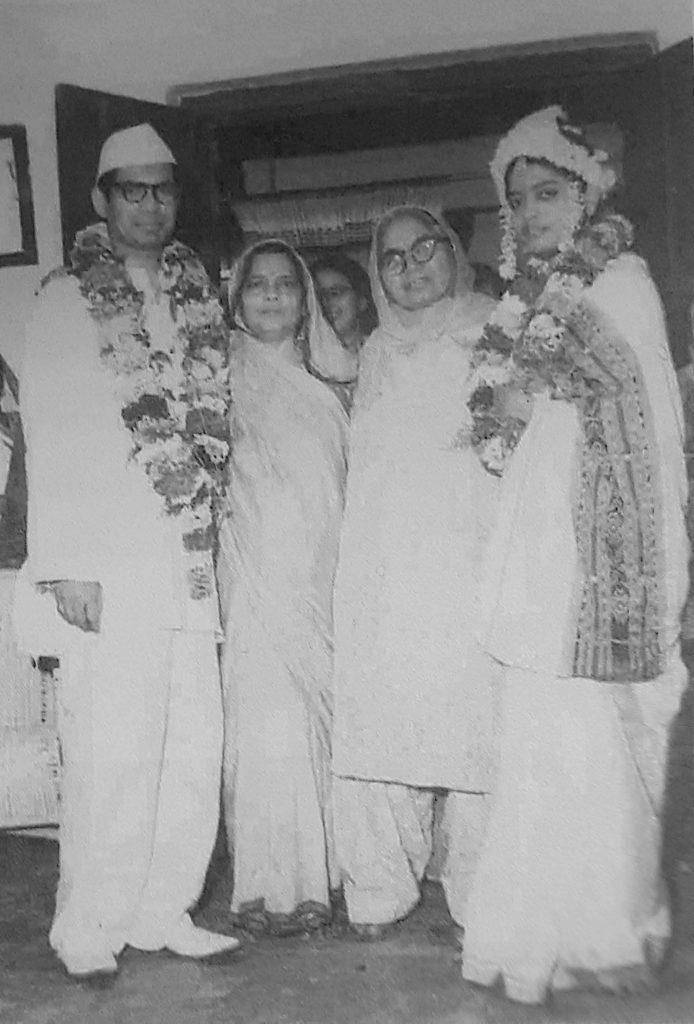

So, eventually we got married in February 1956. She was in the Medical College at Orissa. Hoshiarpur was very far from there. She gave up her job to come to Hoshiarpur. But there was no job in Hoshiarpur; it was a small town. She worked in some schools. She would help some people there if they were ill, and for which they still remember her. So, she made that big sacrifice.

That’s a big sacrifice for sure.

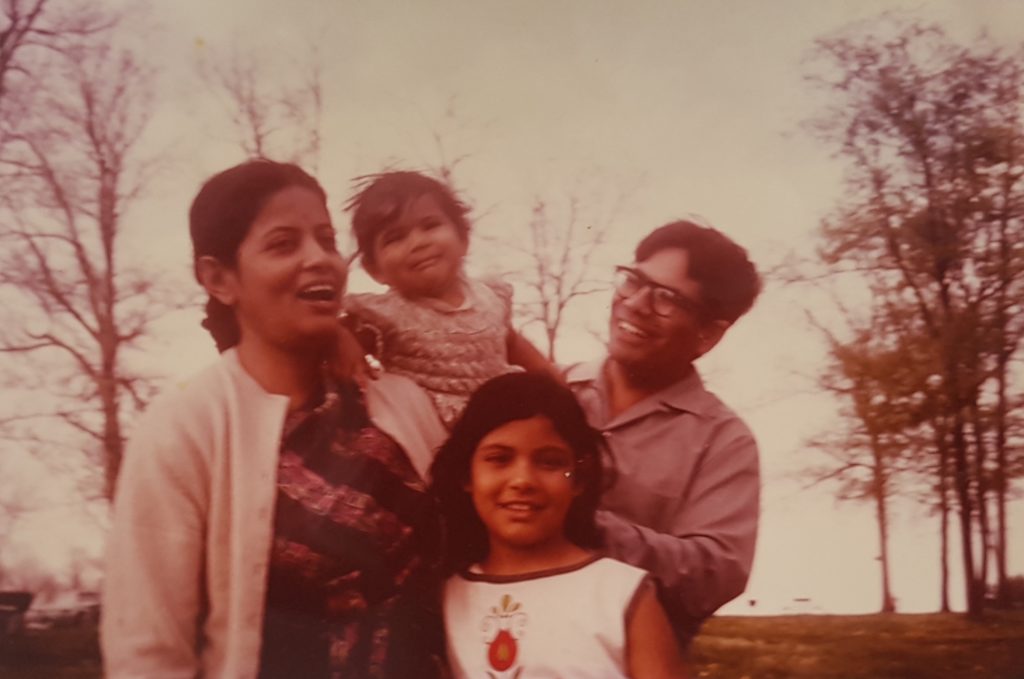

RPB: In ‘57, we went to the University of Notre Dame in America. After the full session, they said, “Why don’t you stay for the summer?”. We stayed on for the summer. Our daughter Bindu was still very young. While we were away, Bindu stayed six months with my parents, and six months with Saudamini’s parents.

By the time we came back, UGC had allotted a Professorship to Panjab University. Joshi said that since they already had a Professor in Pure Mathematics, he would use it for building up Applied Mathematics. UGC replied saying that they had given it for a particular purpose: “If you want it for Applied Mathematics, you are going to have to apply for another other position.” And the university was given a position for Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, with the hope that Auluck would take the position. But Auluck didn’t take it up. So, the Professorship was available, and Joshi appointed me before I returned. I came back to join as Professor. By this time the department had moved to Chandigarh.

So, Professor Gupta and I were now both Professors. Then in due course, other people joined, and we had around nine people in the department. Thus started our journey towards building the department. I have been at the university here from that time on. At one stage in between, I had some differences with people during Joshi’s time. Joshi became very fond of me and thought very well of me, and my wife was very popular here with her medical work. She also had a position in the Pharmacy department, and also in Anatomy and Physiology as a Lecturer, and things were moving quite well.

But owing to serious and irreconcilable differences of opinion in the University Senate, I was compelled to look at positions outside Panjab University. When I handed in my resignation, I was in for a surprise though. A decision was made by the Syndicate, who said that they wouldn’t accept the resignation and had also decided that I would be given long leave. And that they would welcome me anytime I wanted to return. So I got indefinite leave. I went to the U.S., to Ohio State in ‘64 and was quite happy working there. Alan Woods and I became very close to each other. We wrote 12 papers together.

How long were you in Ohio State?

RPB: We went in ‘64 and in ‘67. Then, Joshi retired and a new Vice-Chancellor joined there. He even came to Columbus, and told me that things had changed. “Why don’t you come back,” he asked. I talked to Saudamini, and then eventually we decided. I told the Vice-Chancellor that I would come back for one year. Only if we found that we were comfortable there, we would move back for good. Then I talked to Ross, who was earlier the head of the department in Notre Dame, and who had also moved to head Ohio State’s mathematics department by then. Ross said, “We understand. Whenever you are free, you can come to Ohio.”

That was very generous.

RPB: So we came back to India, and used to go to the U.S. every summer. Woods and I got together and worked together. Eventually, I became the Vice-Chancellor here in Panjab University.