Professor Gupta ji, it is a pleasure to talk to you on behalf of Bhāvanā. I wish you a warm welcome to join us on another episode in our series of conversations with scholars about mathematics, especially in India. Could you please briefly lead us through your early childhood?

RCG: I was born on the day of Raksha Bandhan in Jhansi; it is a Shravan Purnima day [a full moon day in the śrāvakatex is not defined month of the Hindu calendar] and my pet name at home was Poonu because of that. [Laughs] I was educated in Jhansi up to ISC [Indian School Certificate]. In the last year of school, I was in Bipin Bihari Inter College, where I completed my Intermediate science course [a two-year course] of the Uttar Pradesh Board and passed with distinction in physics, chemistry and mathematics in 1953. Since there was no college giving a B.Sc. degree in Jhansi in those days, I obtained my B.Sc. and M.Sc. from Lucknow University. Students who wanted to study science after their Intermediate studies in Jhansi would typically go either to Allahabad, Lucknow, or Sagar, where B.Sc. and M.Sc. were offered.

Did you live in a hostel at that time?

RCG: Oh certainly! I stayed in the Subhash Hostel during the two years of my B.Sc. course, and at Tilak Hostel during the two years of my M.Sc. course, both at Lucknow University.

Was there anyone in your family who had a strong influence on your academics during your formative years?

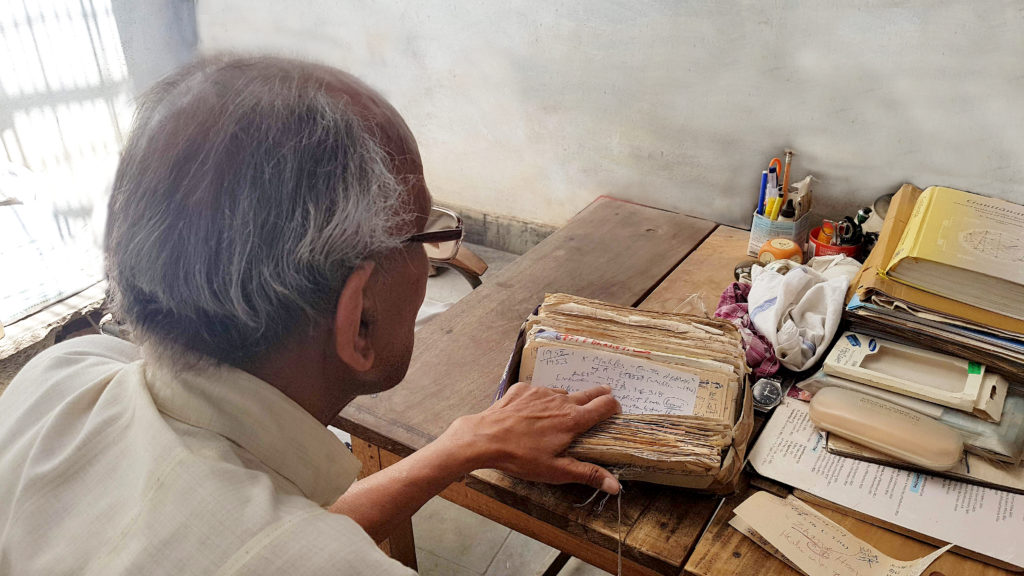

RCG: Actually, there was no such influence. My influence was generally from my teachers, not from the family. I have family records which have the names of my father, grandfather, and so on. We belonged to the business class, the Vaishyas, in Hindu society. Our family spent their time in business in various shops, some of which were rented. My father spent most of his time working as an assistant, what we would call a munim, a person who is employed for keeping accounts. But he maintained an interest in legal affairs and cases, and was also called Munshi-ji.

This was all in Jhansi?

RCG: Yes, I was in Jhansi from 1935, the year I was born, until 1953.

Was Hindi the medium of instruction at your school?

RCG: Yes, except for science.

What are your thoughts about the idea that one’s mother tongue is the best medium of instruction?

RCG: It’s alright, I think. The difficulty lies in translation though. For example, if you want to translate technical words, then you have to evolve dictionaries in regional languages. Further, almost everyday, you have to find hundreds of new words to add. Only then can you cope with new things in the sciences, engineering, and technology.

But do you think, in school education, what we have is enough? You brought up issues with technical words, but that would come only later in school education.

RCG: Ah, school education should be in the mother tongue. But at the same time, if they are taught some other languages, I think there is no harm. In fact, if other languages have to be taught, it should be done in earlier classes, as languages can be picked up easily at that stage. It is more difficult to learn other languages at an older age.

Did science appeal to you during your school days? Do you recollect any incident that made an impression on you, or a striking event that made you want to pursue science?

RCG: I can tell you one good story. Once I visited my maternal uncle’s shop. At this time, I was reading science in school. My uncle asked me “Do you know, when you immerse a coin in water, why does it sink?”. I said that it is because the coin was heavy. Then he corrected me and told me that it was not a question of heaviness but of density.

If other languages have to be taught, it should be done in earlier classes

Then, he carried out an experiment in the shop itself to illustrate this point. It was all very wonderful and unforgettable. He took out the pan of a balance, which was in the shape of a bowl. He took out a bottle of mercury and poured it in the pan. He said, “Alright, you said heavy things will sink. I am now picking up a ser”1—a weight of iron—which he put it in the pan. But it did not sink!

This was because the density of iron is less than the density of mercury. But he did not stop there; no, he was a great teacher. He then took out a gold ring from his finger, and said, “A heavy weight did not sink. Now I’m putting a small ring of gold,” and he put it in and it sank! Oh my god! So he demonstrated that experiment to me. I must have been 10 or 12 years old at the time.

I believed in science always. Because, see, man is a rational animal and things have to be explained in rational terms. My interest in science and my belief in it was there from the very beginning.

When you were 12, India became a free country. That must have been a heady feeling, especially growing up in the town of Jhansi.

RCG: Yes, I remember in 1947 we celebrated in the mohalla [colony]. Some senior of ours collected all of us in the verandah and we sang the national anthem. At that time, one of my cousins was there and he was going to the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh]. He also sang the RSS song.

Did you attend RSS śākhas?

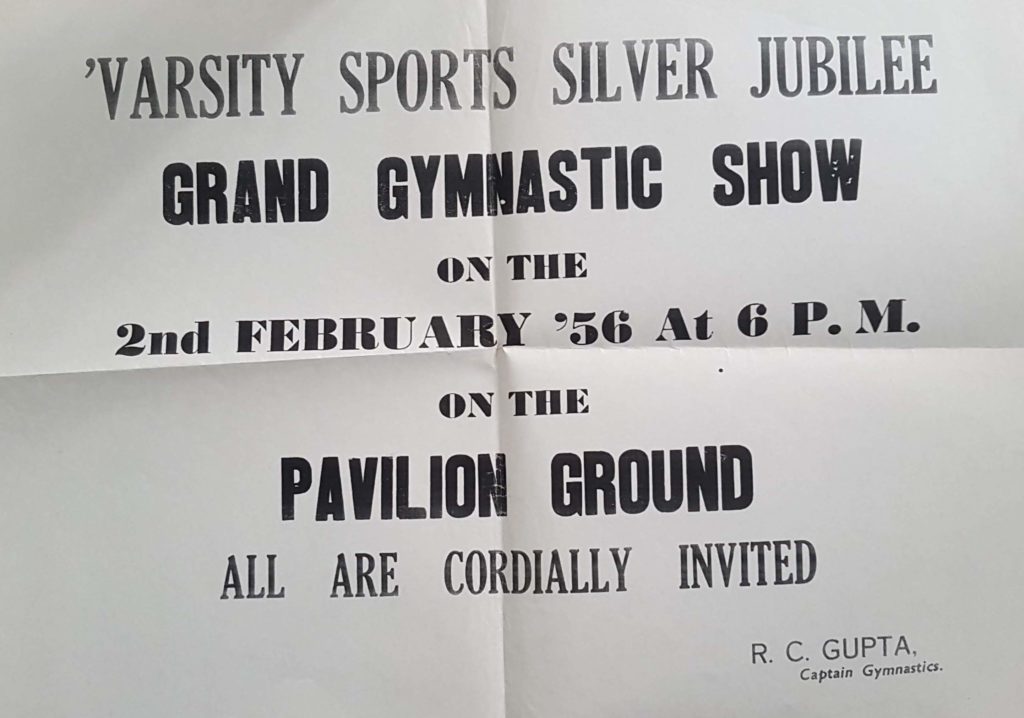

RCG: I went for some time in my childhood. Later, we had a Lakshmi Vyayam Mandir in Jhansi. It was basically a gymnasium but was more than that. They taught Eastern and Western gymnastics and all sorts of other things. They also conducted examinations. I became a regular visitor from my teenage years, and I also passed their exams. I am Vyayam Visharad because I had learnt mallakhamb.2I was also good at gymnastics.

My interest in science and my belief in it was there from the very beginning

When I did my B.Sc. in Lucknow University and lived in the Subhash Hostel, I found there were some students from Vyayam Mandir already there. They were going to a gymnasium that was very close to the hostel. So I could continue my gymnastics and my vyayam there. I won the championship there for two years, and the next year, I became captain. So, I was a Lucknow University gymnastic champion and captain. I was captain for the Sports Silver Jubilee, year 1955–56.

I see! Coming to your work, your career seems to be a rare mix of subjects. You study mathematics as it was practised in the ancient past.

RCG: That is a separate story. I got into ancient mathematics only after my M.Sc. There were no courses on the history of mathematics at all in Lucknow University.

So when did this unusual interest in blending history and mathematics actually begin?

RCG: There is a standard book on the history of Hindu mathematics, by Datta and Singh, published in two volumes, in 1935 and 1938 from Lahore. Even now, it is a standard book. It was, of course, out of print in those days when I was a student but a reprint of it came from Asia Publishing House in 1962. And when that book was reviewed by a foreigner, the review was not favourable. I corresponded with some people and found that this reviewer had taken a similar attitude to that of the person who reviewed the book when it was first published. Anyway, the book which we now find to be a standard book was not favourably reviewed at the time.

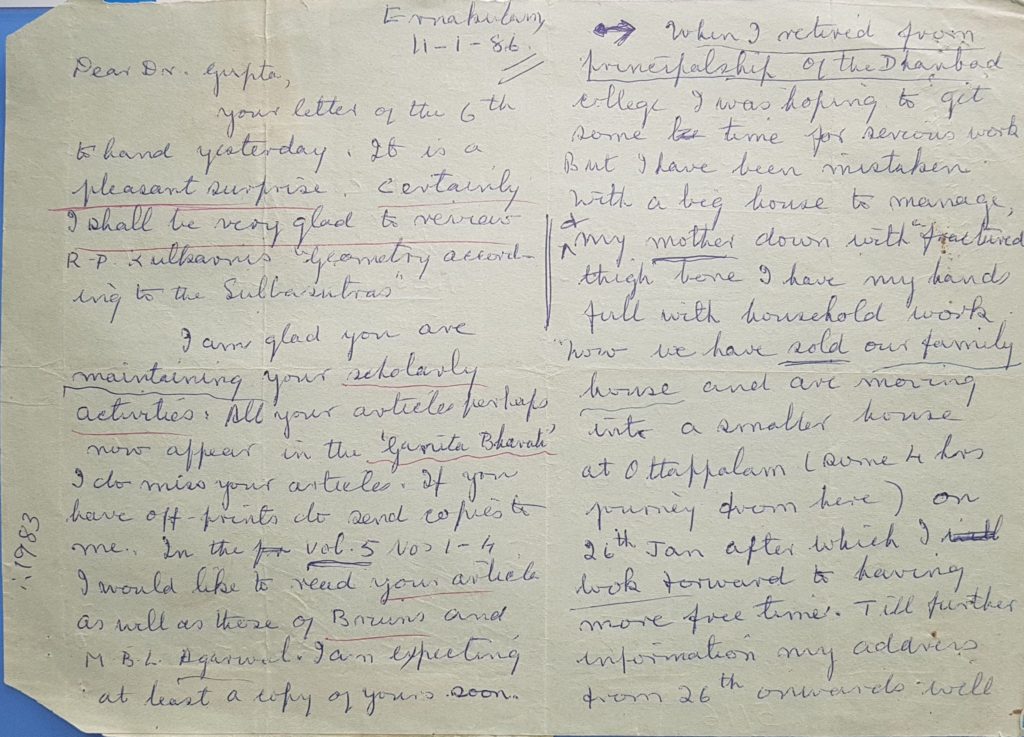

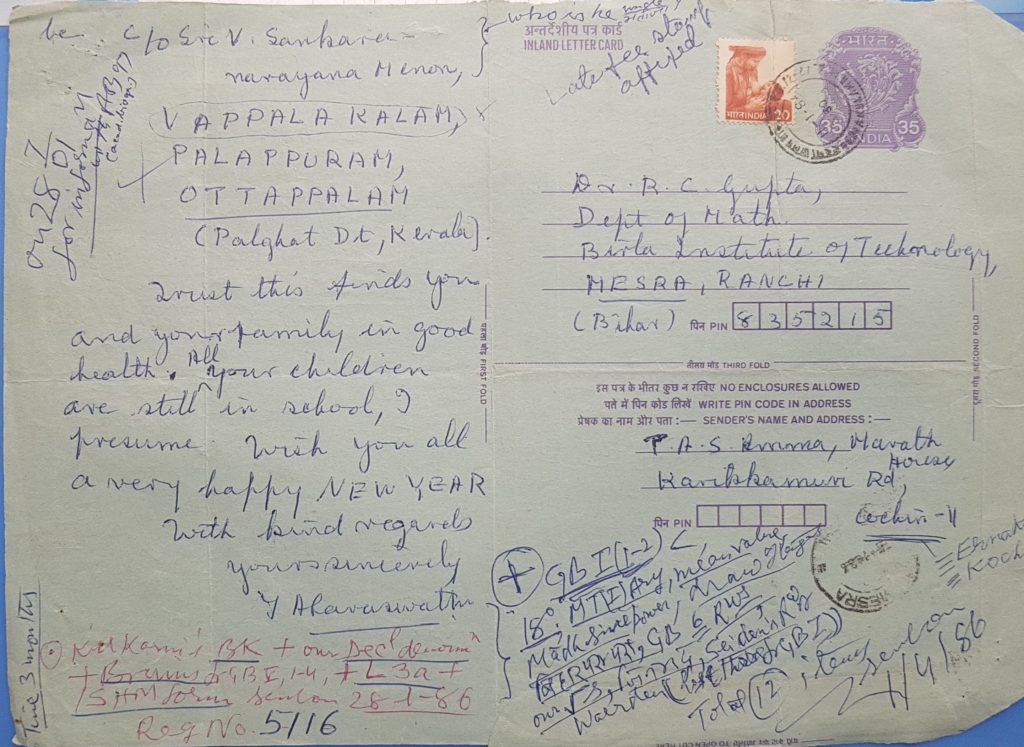

So I decided to devote my life to studying the history of mathematics because at that point in time there was no use of asking who was right or wrong. Fortunately, T.A. Sarasvati Amma3 was in Ranchi, where I was also working. This seemed [to me] to be God’s plan because she belonged to Kerala and came to Ranchi, while I was from Jhansi and went to Ranchi about a thousand kilometres to the east.

She had written a book on geometry in ancient and medieval India4 which is considered a continuation of the book by Datta and Singh.

RCG: That book was not published at the time she completed her PhD. But I came to know about her and contacted her. She agreed to guide me. Arithmetic and algebra were already covered in the two volumes of Datta and Singh, and she had written about geometry herself. The next topic was trigonometry in ancient and medieval India and I did that for my PhD, which I completed in two or three years. I did not know Sanskrit, so I read dictionaries of Sanskrit. We referred to many books and I also consulted her. The main thing was that I was a quick learner and picked up these technical words in Sanskrit.

Especially those that were employed in the mathematical works?

RCG: Yes. For example, in Sanskrit, a sentence may translate as “He was killed by the king.” Some Sanskrit scholars may not know that the mathematical meaning of this is: “It was multiplied by 16.”

[Laughs] The literal meaning was “killed by the king” but the mathematical meaning is “multiplied by 16″!

RCG: Yes. Because the word nṛpa (king) is used for 16. There were hidden numerals (bhūtasankhya): sūrya (sun) is used for 12, candra (moon) is used for 1, bāṇa (arrow) is used for 5, sāgar (sea/ocean) is used for 4. Similarly, the word “eye” is used for 2, while “Mahadev’s eye” or “Shankar’s eye” is used for 3. This usage is all because our Indian culture and tradition is tied into the language. So you need to have an overall knowledge of these sentiments to effectively translate Sanskrit.

I quickly made myself accustomed for doing this kind of research work. At the same time, I looked at many Kannada, Tamil and Telugu works and got the opportunity to consult them. Sarasvati Amma’s mother tongue was Malayalam, so it was surprising when she checked my Sanskrit translation and praised it by saying “Gupta, your translations are quite accurate!” I was able to translate many untranslated stanzas. Many things had not been interpreted correctly, and though I don’t say that I am an expert in Sanskrit, I could pick up some technical words and was able to arrive at many correct interpretations.

In a surprising move, you also went on to earn a diploma in mechanical engineering. How did that come about?

RCG: I joined BIT [Birla Institute of Technology] in 1958, one year after doing my M.Sc. I had served for one year in Lucknow Christian College where I taught a course. At BIT, they first put me in a hostel because the quarters were getting ready. So I told myself that since I am now in an engineering college, in addition to reading many topics in applied mathematics, let me have some knowledge of engineering also. When I saw an advertisement of the British Institute of Engineering Technology for a diploma through postal correspondence, I joined it. For one year, I was receiving their lessons sitting in the hostel at the time and didn’t have much else to do. I did their mechanical engineering course in that year, selecting topics like applied mechanics, which was dynamics and statics, and then heat engines, etc., and then some production planning. By taking these few subjects, I successfully completed their course by post and they gave me a diploma certificate in mechanical engineering.

By the way, I read that you completed your M.Sc. in mathematics from the School of Careers in London?

RCG: This has been printed by mistake somewhere. No, I completed my M.Sc. in mathematics at Lucknow University. After I obtained my M.Sc., I taught temporarily at Lucknow Christian College for a year. The year after that, I got the job in BIT.

Now there is another thing you should know—I was married at the time.

In which year were you married?

RCG: I was married during my first year of B.Sc. itself. I obtained my B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees as a married man. So, why did I marry earlier? It was because at that time the minimum age for marriage was 18 years, for boys. The minimum age is now 21.

My father was poor. I’m also not rich, and by any standard, I’m still poor. At the time, my father said that I must get married, for two reasons. One was that I was senior to my sisters, so unless I’m married, he said, how can he marry off my younger sisters? Secondly, where will the money for their marriage come from? He said that what I would get in dowry from my marriage could be used for this purpose. So, you can say I was compelled to marry. In those days, great men like Gandhiji and others too were married early in their lives.

And you adapt yourself to the changes

RCG: We are adapting. Where is your choti [tuft of hair at the back, also called Shikha]? Every Hindu male has to have one. Where is it?

Yes, it is mostly gone. [Laughs]

RCG: There is a joke, in this context. When, some years ago, the Hindu men stopped having chotis, the girls were having two chotis [braids or plaits]. Many times, we would joke that they had to compensate!

Hindus believe in God. But in a true sense, if you believe in God, then you have to believe that God is in everybody’s heart. Similarly, if you talk of varṇāśrama system, you have to devote almost one-fourth of your life for each stage—brahmacharya, gṛhastha, vānaprastha, and sanyāsa. But what is happening nowadays? People are not ready to go beyond gṛhastha. Those who are occupying the chair are not willing to leave the chair until they die. Similarly, there is dharma, artha, kāma, and mokṣa. But here again, one is not going beyond kāma and artha. So if you say half here and half there, your chance of being a true Hindu is only one-fourth.

You see, I am now old enough that I can connect all these things in a consistent and coherent way.

Why did you choose the town of Ranchi for your job?

RCG: I did not choose it as such; it was the first permanent job I got. As I said, I was in Lucknow at Lucknow Christian College for one year before I joined BIT. I had got this temporary job because there was a person who taught at the Intermediate level, Ved Prakash Menera, who took leave for one year for some reason, and so I got that post for a year.

You see, I had topped in my M.Sc. class. Then, during interviews at the college, I got two jobs. One was in Kānyakubja College, which had a salary of 200 rupees a month. I preferred the job at Lucknow Christian College where it was 150 rupees a month with a dearness allowance of 20 rupees per month. People also used to do an M.A. in mathematics in those days. And in the M.A. course, another student had topped. He also applied for the same job as me, but because the Intermediate students to be taught were science students, I got selected.

My job at BIT was the first and last job in my life. I had also applied to some new colleges that had opened in U.P. [Uttar Pradesh]. Once, the post of Lecturer in History of Science was available in Delhi University, for which I had applied. Similarly, I applied to BHU [Banaras Hindu University], because I was reading Sanskrit and I thought BHU was a better place for it. Though they selected me, they did not offer me associate professorship or a readership position, only a lecturer position. I was already a lecturer in BIT, so I did not see why I should move elsewhere.

Anyway, by that time, I was already doing more work in the history of mathematics. After K.S. Shukla’s retirement, perhaps they could have advertised [for new job applicants] and made it clear they wanted a person to work in their Hindu Mathematics section. Perhaps I could have joined but they did not pay attention to this requirement [of hiring someone who worked in the history of Hindu mathematics]. So, after Shukla’s retirement, the study of Hindu mathematics in Lucknow University did not continue in the true sense, and other things also did matter.

What were your teaching and research responsibilities when you joined BIT Mesra?

RCG: I was taking classes for undergraduate students in mathematics.

But there you did not have an opportunity to teach history of mathematics.

RCG: There was no course on it.

Did you include tidbits from the history of Hindu mathematics anywhere in your teaching?

RCG: No, I did not have the liberty to do so. This is not the American system where the teachers can offer courses of their interest. In India, if you teach things outside the syllabus, you will be in trouble for wasting students’ time! But still, what I could do later on was to make my classes more interesting. Otherwise, I thought I was not bad as a teacher.

Didn’t you start a research centre for the history of science at BIT Mesra? Very few places in India pursued the history of science during those days.

RCG: That was later. When more recognition came to me, BIT became interested. There is no doubt that the Birlas are interested in Indian culture and science. They had a professor there who was teaching courses on Indian culture. They also wanted to have some work in the history of science because they saw my publications and the recognition I was receiving. So, BIT became interested in the history of science.

There is no doubt that the Birlas are interested in Indian culture and science.

When did this start?

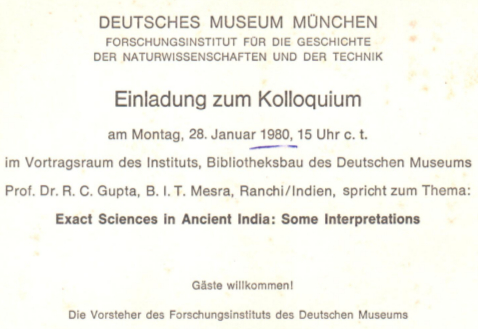

RCG: These are all after 1980. I was made Professor only in the 1980s.

They did not expect us to teach courses on the history of science. They wanted to have a centre so that we could do some projects and possibly get grants. But that did not materialize, and also, the UGC [University Grants Commission] did not approve the courses. I was otherwise a regular teacher in mathematics. When post-graduate courses were started, I taught mathematics courses to those students. At the research centre we continued some work—we had a project and a scholar for some time.

Coming back to Sarasvati Amma, what were the circumstances under which you met her? And what role did she play in establishing a thriving school of the history of Indian mathematics?

RCG: I had already decided to work on the history of Hindu mathematics after reading the unfavourable review of Datta and Singh’s book. She agreed to guide me when I approached her.

But she first spent some time in publishing her book, which took about ten years or so. Since her guide [thesis advisor], V. Raghavan, was a famous man, Motilal Banarsidass recognized his name and decided to publish the book. Ranchi University also gave a subsidy to this publisher for the book. And so it was published.

Around the time of this book’s publication, Dr. Sarasvati joined as principal at Women’s College, Dhanbad. But then she found herself entangled in administrative work and could not build up any school of thought. But I could build on these things and started Gaṇita Bhāratī.

Was she the guiding hand for you when, in 1979, you founded Gaṇita Bhāratī?

RCG: Actually, that started after my work for the International Commission on the History of Mathematics in January 1972. There were two jobs for this Commission. One was to publish a directory of historians of mathematics all over the world. For the Indian part of the work, I collected the names of all Indians who were interested in the history of mathematics. For this, I even sent a general circular to all the universities and I got some good names. I sent the whole list to be included in the directory, which appeared in 1972 itself. The second job of the commission was to start the international journal Historia Mathematica, and so it was started in 1974.

Before this time, the International Commission on the History of Mathematics was formed separately to look after the history of mathematics in 1971. Several decades earlier, the International Commission on the History of Science and Technology (a division for the History of Science) had been established, but, until then, there hadn’t been a Commission that was more specialized in the history of mathematics.

There was one difficulty at the time. Indian scholars, generally, would not know which foreign journals were being published in their field and how to get them, and how to pay in dollars. The Commission authorized me to manage these things initially, and I told scholars that they could pay in rupees for Volume 1. I collected their money for subscriptions and they received the journal. I spent the money for promoting the cause of the journal Historia Mathematica in India. I was the Indian Representative on the Commission and so some subscriptions were sent to me. Also, things were cheap at that time; for example, the Directory cost mere $2 (= Rs. 16 only) to listees.

So how exactly did Gaṇita Bhāratī come about?

RCG: Gaṇita Bhāratī came later on. By this time, Historia Mathematica had started.

Then, in 1973, Copernicus’ 500th birth anniversary was celebrated all over the world. During the same year, al-Biruni’s millenial birth anniversary was also celebrated. From India’s point of view, these foreigners were being talked about in the world—but what about Indian scientists? Around this time, the first Indian satellite was being prepared for launch in Moscow. Āryabhaṭa’s name was suggested for the satellite because he was born in 476 AD. So more than a thousand years after his birth, a satellite was named after him.

A conference [International Seminar on Āryabhaṭa] was held by the Indian National Science Academy around this time. Not many people were doing research in the history of mathematics, but because of the satellite Aryabhata, people wanted to learn more about the history of mathematics in India. The idea was floated to form a society and so the Indian Society for History of Mathematics was formed in 1976. The head of the mathematics department at Delhi University, U.N. Singh, organised the initial meeting that formed the society. And naturally, R.C. Gupta would become the first life member!

More than a thousand years after Āryabhaṭa’s birth, a satellite was named after him

When I attended the meeting in 1978 in Hyderabad, I suggested there should be a journal. They appointed me as the editor in that meeting itself to bring out the journal.

How did you come to name it Gaṇita Bhāratī? Did you name it?

RCG: I named it. It was resolved in the Hyderabad meeting that R.C. Gupta is interested in starting a journal. I chose the name Gaṇita Bhāratī. In December 1978, I said I will bring the first issue in 1979. You know, I did not wait for the sanctioning of this journal and had sent letters even earlier to solicit a few articles. The very first issue was published in time in June/July 1979 and I paid the bill from my own pocket.

Because you wanted to publish on time?

RCG: Yes. I thought that since the society had appointed me as editor, they would pay some day. After all, the society had just started and membership had to build up. We could not quickly become rich, so I did not wait for reimbursement during the first year. Similarly the second issue was also printed. Volume 1, both the issues, were printed and paid for by me. At that time, it was not very costly to do so. Later on, they suggested to me that they would print it in Delhi instead of Ranchi, and that I would remain editor while the treasurer and the managing editor will manage the printing. So I had nothing to do except inviting, refereeing and editing articles from Volume 2 onwards.

I was wondering about the “Bhāratī” in the name, because in amarakośa, the Sanskrit dictionary, I think there is this reference—brāhmī tu bhāratī bhāshā. So does “Bhāratī” also refer to Sanskrit?

RCG: Sarasvati is also called Bhāratī. One should not forget that, in Sanskrit, one word has many meanings, and that many words have the same meaning. For the word “surya” [sun], “ravi” is also there. We have the “sahasranām” for Vishnu. Hence, “Gaṇita Bhāratī” has many meanings. Similarly, “Gaṇitānanda” can have two meanings—it can be the “joy of mathematics” or “one who finds joy in mathematics”. As it happens, I myself wrote many articles under the pseudonym of “Gaṇitānand”.

It is said that traditional Hindu practices strongly guided the development of mathematics in India many millennia ago. What specific human activity in your opinion were the strongest motivations for our ancient thinkers to invent or discover mathematical tools?