A mathematical breakthrough is more than the sum of its parts. It is not merely a scholarly achievement but rather the triumph of years of sacrifice of those who toiled hard to realise it. The same is true of the lives of dedicated practitioners who played their part in the long saga. Only the sacrifice and toils are not just confined to them, but also afforded by those loved ones who support them in their travails. Harish-Chandra was one of the greatest mathematicians to emerge out of the Indian landscape. His remarkable accomplishments were borne out of long hours of immersion in the mathematical world, which needed an unfettered state of mind without worldly interruptions. Apart from his own strength of will, it was his wife, Lalitha Harish-Chandra, who made this possible. Throughout Harish-Chandra’s prolific career, Lily, as she was affectionately called, was his pillar of support.

But Lily was also much more than that. Her charming persona and benevolent disposition left a lasting impression on anyone who had the good fortune to make her acquaintance, and the reminiscences recorded here testify to the same. Indeed, her uncanny ability to play the perfect host as mentioned by the visitors to the Harish-Chandras’ residence at Princeton, made it a welcoming abode for family, friends, and many an unsuspecting but pleasantly surprised mathematician. The memories revisited here stand as testimonials to the life of a kind, loving and generous soul, who brought joy to all who knew her, and at the same time played an irreplaceable part in the life of a great mathematician of our time.

Premala Chandra

Having lived her whole life among scientists, my mother instinctively understood our strengths, our challenges and our quirks often better than we did ourselves.

My mother always brought out the best in all of us. This was most evident with my mathematician father. He was inspiring yet impossible, and my mother worked hard to polish his many metaphorical edges. He had been a lodger in her parents’ house when she was a girl, and then she used to play lots of mischievous pranks on him. Throughout my father’s life, my mother continued to bring out the playful, smiling, better sides of him, connecting him with the real world despite his many half-hearted protests. My mother read widely and told my father about the books she enjoyed. He would listen carefully, and then he would often proceed to repeat her descriptions to others who marveled at his cultural breadth. When I called my father on this at family dinners, my parents both smiled. My father told me that he could not live without my mother, and in later years his photo was always near her.

I was born in a flurry of Polish. My mother’s doctors, noting her Warsaw birthplace, thought this would be comforting and my mother was too polite to say that she could not understand. Not only did my mother give me life but she effectively saved my life as well. As a child I had terrible asthma. I spent far too much time in emergency rooms and I missed two full years of school. The doctors wrote me off as an invalid. My mother’s response was to sign me up for a swim team. She found a coach who had asthma himself and had made it to the Olympics. He had placed fourth there and he certainly took that out on us! Slowly I did in fact get healthier, and happily I have been able to defy the doctor’s predictions.

Once my lungs were on track to being in order, my mother felt it was time to work on my social skills. This proved to be more challenging. She was concerned by how I presented myself. My mother tried to address this by giving me a clothing allowance, and was horrified when I spent it on books. She was thrilled when my teenage friends started coming to the house, though it soon became clear to all that they were there to see her and not me!

My mother managed a lively household of my grandmother, my father, my sister and myself with much grace despite many challenges. She believed in living your life on your own terms and following your passions. I really enjoyed math and science in high school but after some “seriously active discussions” with my mathematician father I decided to switch gears and to study history in college. During my second year, my mother sat me down and asked me what I was doing. I was confused since on paper my new approach was working out quite well. “You are just running away from what you love,” she told me, and then the usual refrain, “and of course you would make such a good medical doctor.” This continued to be an active topic of discussion well beyond the time that I had finished my graduate studies in theoretical condensed matter physics. My mother was tenacious and did not give up easily!

As a woman physicist, I look to my mother and my “math aunts” as powerful female role models for their collective ability to manage life’s many challenges with grace and fortitude; these ladies, strongly linked to the mathematics community, maintain multi-decade friendships that often reach into the next generation. I am also deeply appreciative of my mother’s delight in my many opportunities, both professional and personal, and I try my very best to encourage young people in a similar way.

I am tremendously proud and honored to be Lily’s daughter. Later this year I will become a grandmother. When asked for tips about my upcoming family role, my sons told me to take my cues from my mother. This will be a wonderful way to cherish precious memories of her while moving forward, trying to embody all that she has taught me through her loving and inspiring example.

Known as Premi to family, friends and colleagues, Premala Chandra is the elder of Lily and Harish-Chandra’s two daughters, and is a Professor of Physics at Rutgers University.

Devaki Chandra

Our mother was eclectic in her embrace of culture. A good adjective to describe her was inclusive. She was rooted in the Indian culture of her youth, its deep history, literature, music, and more recently, scientific achievement. She marvelled at India’s economic growth since Independence, as she remembered virtually no modern manufacturing taking place there before it.

She had wanted to go abroad and she was able to move to the US. Here she embraced the ethos of self-improvement, taking advantage of local opportunities, developing resilience, and treating people with respect. She encouraged us to do sports, where we learned how to pull together and build resilience, in addition to getting exercise. She used to say that rebirth was part of the Hindu philosophy, whether through learning from your mistakes, becoming more open-minded, or even remaking your life as circumstances required it.

In the back of her existence was her Polish family, most of whom did not survive World War II. Her mother was able to escape to India with her Indian father, another part of her Indian roots. It was probably the biggest reason she was inclusive, as India had received her parents even when it wasn’t clear to most Indians everything that was happening in the war at the time.

There were two survivors from our grandmother’s family whom we actually got to know: a brother, who escaped to Venezuela, and a family friend from Warsaw, who was eventually able to join the Resistance in France. Our great-uncle used to visit us on his way to Europe. Paul Santerre, the family friend, I saw in New York. He enjoyed coming to New York, with its cultural life and cafés like those in Paris. He used to tell me, however, that the thought of what his sister-in-law had been through depressed him. Her child had been killed right in front of her. He himself had survived by jumping between two moving trains on the way to being taken. He was willing to take the risk, as he thought that he was destined to die anyway.

There were two teachers who made a lasting impression on our mother in Bangalore. The first was a French nun, Mother Marguerite, who taught her in the convent my mother first went to. She volunteered her services at the time of the 1971 Bangladesh War. We met her in 1973 when she came to the US to raise money for those affected by it. Our mother always said that the conditions that she saw the nuns endure in India represented religion at its best.

The second teacher was at Bishop Cotton Girls’ School, a Miss Hardy. Miss Hardy encouraged deeper learning that was not consistent with what our mother described as the exam-oriented curriculum of her youth. It made an impression on our mother, as she saw better how one subject related to another, rather than “mugging” for an individual exam. More importantly, Miss Hardy used to impress on her students not to judge too harshly those who had endured war or other crises. That was relevant in the 1940s. Outsiders couldn’t understand the kind of false choices people had to make to survive, whether in stealing or in marital infidelity that could save a child. She would give her students questions to test how they would respond in circumstances of hardship, a bit like a prisoner’s dilemma,1 to see how they might have reacted in similar situations. The lessons from her stayed with our mother for the rest of her life. She certainly brought this up when Soviets started emigrating to the US after 1991, but before that with those affected by the Vietnam War.

In sum, our mother taught us resilience and inclusiveness. Self-improvement and family harmony were important, either towards academic achievement or adjusting to one’s circumstances. Inclusiveness was fully consistent with those ideals.

Devaki Chandra, known as Dini to family and friends, is the younger daughter of Lily and Harish-Chandra. She lives in Berkeley with her biologist husband John Kuriyan and has two daughters. She teaches mathematics and economics in a summer program.

Sigurdur Helgason

Back in 1960 I had accepted a position at MIT but wanted to stay the first year at Columbia (where I also had an offer) in order to benefit from the presence of Harish-Chandra. As urged by the chairman Sammy [Samuel] Eilenberg, I gave a course on Lie groups that entire year.

Chevalley’s book on Lie groups was then a standard reference but I decided on a very different approach. I had the benefit of sharing an office with Harish and could discuss with him my approach which, later in 1962, became a chapter of a book. That year Harish was in charge of the weekly mathematics colloquium. After each meeting, most of us had dinner at the faculty club. After dinner, many of us would walk over to Harish’s apartment where Lily would welcome all of us—Sammy Eilenberg, Serge Lang, Jim Eells, Ellis Kolchin and some others. At that time Harish began to experience some medical problems but he always met his classes (on the Minkowski–Siegel theory of quadratic forms), a course which Kolchin and I followed.

A few years later Harish and Lily settled at the Institute in Princeton. During my first years there, 1964–66, I visited them often in their house on Battle Road, and Lily was always charming and welcoming. At the Institute, Harish and I often had long and serious discussions. I had an office next to his and to my surprise, I often heard him through the wall, happily singing at his desk.

After Harish’s death, Lily established contact with visitors to the Institute who knew Harish from earlier years. Once when I was attending an AMS meeting at the nearby Rider College, I called her up and she invited me to her house for lunch. We dwelled at length on old times and on the stresses caused by Harish’s poor health, which eventually led to his premature death.

In the summer of 1972, there was an AMS meeting on homogeneous spaces at the campus of Williamstown. Although Harish did not lecture there, he did attend and his work was presented by Varadarajan in one of the main lecture series. Harish and Lily stayed at a nearby hotel and I still remember the large green field on which they walked over to the campus the first morning. With her colourful sari, they really looked like a regal couple. It is an image which I clearly and pleasantly remember.

Sigurdur Helgason is Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at MIT. He was with Harish-Chandra for over a year at Columbia University, and was a longtime friend of Lily and Harish-Chandra.

Roger Howe

I met Lily Harish-Chandra through Harish-Chandra. This was not the rule for friends of Lily, since she was much more socially inclined than he, and probably knew many more people overall. However, it is quite normal for mathematicians, of which I am one.

I didn’t get to know Lily very well until after Harish-Chandra died. In fact, indirectly, it was because of his death that I had the pleasure of getting to know her better. Harish had been elected to the National Academy of Sciences in the spring of his last year, and the NAS has a practice of publishing biographical memoirs for its deceased members. I was asked to write the memoir for Harish, and a good portion of my research for the undertaking was to seek reminiscences from Lily and their daughters, Premala and Devaki. Through this, I learned much about the whole family. It was a family of highly capable individuals, with high and rigorous standards. Lily was the glue that held everything together, and provided the support that enabled the girls to prosper, and Harish to maintain his punishing research efforts. After he suffered the nervous breakdown from his initial failure to establish the local integrability of characters, Harish was advised to take summer vacations, to provide relief from the otherwise constant pressure. For the next 20 years, Lily organized these sojourns in various peaceful places, especially Eaglesmere, Pennsylvania. When Harish had his first heart attack, she reworked her recipes in order to provide meals that were heart-healthy as well as enjoyable.

I visited Lily several times to interview her for the memoir, and this gave rise to a practice of visiting her on most occasions when I went to Princeton for whatever reason. Later, after she moved from 95 Battle Road, their home while Harish worked at IAS, to Windrows, a retirement community just north of Princeton, I would make the short trip from IAS to visit her there also, often with others, and often for dinner. At either place, she was a consistently gracious hostess, very attentive to her guests’ interests and concerns, always prepared to advance the conversation, which at Windrows sometimes lasted well beyond dinner. She was also a doting grandmother, always ready to share the latest news of her grandsons, Adrian and Bryn.

The consistent effort to make other people’s lives better was characteristic of her

Our son, Nick, attended Princeton University during 1989–93, and when we went to visit him, we would often get in touch with Lily. Nick joined the Princeton Mime Troupe, and their shows gave us specific reasons for visiting. On one occasion, we invited Lily to attend the show. She accepted, and also invited André Weil, who had been a close friend of Harish. Lily maintained the relationship after Harish died, and especially took pains to connect with Weil after the death of his wife. This thoughtfulness, and the consistent effort to make other people’s lives better, was characteristic of her. They deserve celebration, and I am happy to have the chance to do it here.

Roger Howe is William Kenan Jr. Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at Yale University, and Curtis D. Roberts Endowed Chair in Mathematics Education and Distinguished Professor at Texas A&M University. He is the author of the biographical memoir of Harish-Chandra for the National Academy of Sciences, and is a longtime family friend of Lily and Harish-Chandra.

Vijaya Nagarajan (née Jatkar)

I first met Lily when she had just arrived in Bangalore as a six- or seven-year-old and my family, being Maharashtrian like her father, Dr. Kale, took me to meet her. I was also the same age, just a month older than her. Her face lit up with a smile at meeting someone her own age and she started engaging with me right away. That ability to make a connection with anyone she met regardless of age was extraordinary.

We saw each other almost every day until we were about 15 and she has recounted that magical time in another article.2.} After she married and moved to the US we corresponded regularly. I moved to the US in the early 1960s, but met up with her around ’63 briefly in New York when Harish was still at Columbia.

We talked often on the telephone and met up with her a few times in the UK and also at Princeton. On one such occasion, we spent a few days in the Lake district and it rained quite heavily a good bit of the time we were there. Whilst my husband and I regretted very much that the sun did not shine, Lily just kept enthusing about the sights and did not mind the rain at all. Her enthusiasm and positive attitude to life never failed.

Her interest in others never faded. When we spoke on the phone she was always inquiring about friends and family and we would go down memory lane about their whereabouts, etc.

She faced the premature loss of her husband and ill health in her later years with immense fortitude. When we last spoke in January, she was urging me and my husband to visit her in the spring.

A dear friend and chum—I will miss her very much.

Vijaya Nagarajan is a childhood friend of Lily’s from their years at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, where Vijaya’s father was in the faculty of the Department of General Chemistry. She now lives in the UK with her husband Mangalam Nagarajan.

Suresh Chandra

It was August 1952, and I was travelling in the south with a friend. On reaching Mysore, I got in touch with Dr. Kale who invited me for a picnic. Learning that my friend and Lily had been in the same nursery school in Allahabad, the invitation was also extended to him. This was the first time I met Lily and her parents. We were received with warmth and affection that I will never forget.

Lily, a tall, slim girl in a white cotton saree greeted us with a charming smile. The afternoon was an idyllic one—the beautiful picnic spot, the relaxed, comfortable atmosphere and the delightful company; time flew by. On the way back, as if the afternoon meeting was incomplete, Mrs. Kale invited us home for a pot-luck dinner. My being a vegetarian presented some awkwardness when the soup was followed by fried fish, but I did not want to let it spoil the fun of the evening; this is how my vegetarianism ended. Even today, fried/grilled non-smelly fish is the one non-vegetarian dish I relish.

Back in college, I later wrote to my parents about the trip—although the letter was primarily about the Kale family’s hospitality and how the Lily they knew had transformed from a naughty eleven-year-old who, as Harish once said, would tease and distract him in his study, into a charming, confident, sophisticated young lady. Subsequently, in October, while visiting my parents, my interaction with the Kales and my impression of Lily were subjects that came up again.

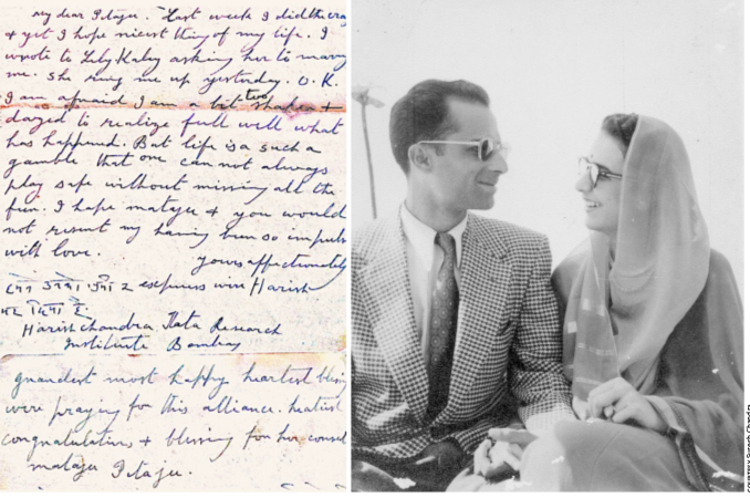

Therefore it did not surprise me when, in early November of 1952, I received a letter from my mother (I have preserved it). She reproduced Harish’s letter dated 9 November, addressed to father, which read:

My mother’s letter records my parents’ happiness over this development. They cabled him:

After their wedding at the end of December 1952, on the 28th to be precise, in Mysore, the couple came to Allahabad to meet with the parents, while I was there on New Year vacation. Their picture as a couple, on a boat at the confluence of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna, taken by me, is reproduced here.

After 1952, we briefly met in 1955 when she came after her father’s passing away. Thereafter there was little contact for many years, except for the occasional exchange of letters.

Sometime after my father’s death in April 1974, Lily and Harish proposed that our mother should visit them. A regular exchange of letters between Lily and my parents had already established a bond of respect and affection for each other. Mataji loved the idea and also the prospect of getting to know Lily more intimately, be with her son and enjoy her [only] two granddaughters—whom she had not yet seen. However, the challenges she faced were formidable; she had never travelled by air and it was a long journey, she was 79 and also an orthodox Hindu vegetarian lady and lastly, although she could read and write English, she was not fluent in speaking the language. She took some time to come to a decision, but being a lady with guts and determination, she agreed, and a four-month visit was fixed for the summer of 1975. Credit goes to both, but primarily to Lily, who took care of her mother-in-law’s sensitivities so willingly and conscientiously that both became exceedingly fond of each other. Mataji was full of praise—despite running a household, taking care of the education and development of their daughters and meeting social obligations, Lily took care of her aged mother-in-law wonderfully, ensuring her stay was comfortable and memorable. Mataji was convinced that Lily’s unwavering support was a major factor for Harish’s single-minded pursuit of pure mathematics, and his success in it.

(Right) Harish-Chandra and Lily in Allahabad soon after the wedding Suresh Chandra

In the early `80s, I found myself visiting the US East Coast for short business trips. I made it a point to always squeeze out time, howsoever short, to visit Princeton. In the first such visit, I discovered that the gap of almost 25 years, since the previous meeting in 1955, had made no difference in our warmth for each other. Lily would always meet me at the railway station. Harish, most of the time, was immersed in his work and it was with Lily that I would spend the limited time. We would discover that there was so much to talk and know about each other that we had missed during the years lost. One of these short visits was to San Francisco. We took advantage of the time difference, and Lily and I would chat on the phone when she was up and about, and jet lag would not let me sleep. I always remembered all these short trips as my visits to Lily.

My last such visit, very fortunately, was in the third week of September 1983, and was very different. I had time to stay for two-and-a-half days. On this occasion, I found Harish very relaxed and, unlike previous visits, he was ready to spend considerable time with me. I remember the sunny morning he sat with me in the backyard, chatting extensively about things back home. He posed for photographs with Lily. In the afternoon, we went for a long walk on the grounds where the Battle of Princeton was fought. The next morning he took me on one of his favourite walks behind the Institute. The biggest surprise was the day I left—he drove me to the railway station, waited for the train to move and waved goodbye for as long as we could see each other. And this was the last we saw of each other. This turned out to be the farewell visit to Harish.

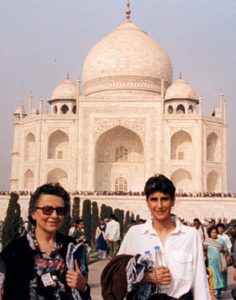

In the summer of 2001, my wife Kshama and I planned, with Lily’s cooperation, a three-and-a-half month long holiday; her house on 95, Battle Road was to be our base. True to her characteristic generosity, Lily presented us with a train ticket to travel along the coastal route from San Francisco to San José; it was absolutely beautiful. In all, we must have spent a total of four weeks with her. She would take us out for lunch to the Institute, Princeton University and various restaurants. We discovered her wide circle of friends and could see how the Indian community there looked up to her as their representative and a leader of sorts. Almost all her close friends invited us to their homes. For this visit, Lily had laid down the condition that we have to be with her on Thanksgiving day. In the US, we have, in considerable numbers, younger members of our extended family; she established the tradition of inviting them to 95, Battle Road for Thanksgiving. Many would join with their spouses and children to make for a merry gathering. In the last ten days of November were birthdays of Lily and two others. She established the tradition of celebrating all three birthdays together on Thanksgiving day. I hope this tradition continues in her memory.

The last I saw her was in May of 2006, when at her insistence, Kshama and I travelled to the US to attend her grandson Adrian’s graduation ceremony. Regular phone calls between us over the last many years became a kind of ritual. For the past few years, she was wheelchair-bound and had some age-related issues limiting her activities. But from our telephonic talks, we knew that she did not let that come in the way of maintaining her contacts with the family, entertaining visitors and friends and getting entertained.

Whenever our telephone would ring in the mornings of birthdays, anniversaries and other important occasions, our guess invariably was that we will hear “This is Lily calling from Princeton.” Those were long chats which left an impression that we had met in person. Those calls will now be only missed.

Suresh Chandra is the younger brother of Harish-Chandra. He lives in Gurgaon with his wife Kshama, two sons and their families.

Kshama Suresh Chandra

I married Suresh, Harish’s younger brother, in 1957 but it took me 30 years to meet Lily. During this long period what I learned about Lily came from Harish during his only two visits in 1964–65 and in 1972. Yet, in 1987, during our visit to the US when Suresh and I got down from the train at Princeton, where Lily had come to receive us, I felt that two long lost friends were meeting. Ever since then, we got along very well. She had reasons to visit India thrice during the decade of the ’90s. The high point was when Lily came, in December 2000, with her whole family—both daughters, sons-in-law and the two grandsons. We, our two sons, their wives and five daughters, have our dwellings in one building. So it was only natural that they were all hosted by us. It was a grand union of the two families culminating in a celebration of Christmas and New Year. In return, the two of us planned a long tourist visit to the US making her house as the base to visit various parts of the US and come back again and again to be in her company to relax. We paid another shorter visit in 2006 essentially to attend Adrian’s graduation ceremony. I have written all this to make the point that how the bond of affection developed and brought us so close.

For the next ten years, both of us had no occasion to visit each other. The lack of face-to-face contact was replaced by long and rambling telephonic chats at regular intervals. These covered, besides everything else, exchange of information about closer members of the larger family in India and similar members in the US with whom Lily always maintained contact. Visitors from India would make it a point to establish contact, personal or telephonic, with Lily. She would often tell her friends or their children coming to Delhi to establish contact with us for local guidance and help. They were always welcomed by us and few of them accepted our hospitality and stayed with us.

In these ten years, she had developed serious knee problems and muscle weakness. Even after total knee replacements, she found it difficult to stand on her legs, and had become wheelchair-bound. She decided to sell her large 95, Battle Road house and move into a smaller apartment in a beautiful complex, Windrows, meant for senior citizens. In the summer of 2016, Suresh’s grand-niece, living in New York, was getting married. We had been invited. It was decided that I would go. The added attraction was not only to meet with Lily again but to spend some days with her in her new surroundings. I had a lovely and satisfying stay with her in her apartment for a week. I met a number of her friends whom she would invite to meet with me. I admired the remarkable way she pulled herself out of her problems and lived her new life all alone on a wheelchair with enjoyment, grace and dignity, challenging her disabilities. I noticed that having moved from the vicinity of the Institute did not come in the way of her keeping in touch with the mathematics community.

Her sudden passing away, this January, has created a vacuum that cannot be filled. It was a shock not only to us but I think to all who knew her. The attendance at her funeral and her memorial is a testimony to the love, affection and respect with which she was held by the mathematical and Indian communities and her numerous friends and admirers in Princeton. Premi and Piers3 brought her ashes to India for the final resting place of her mortal remains to be in the waters of river Ganga at Rishikesh. Suresh and I joined in there to pay our last respects.

A fair part of the credit for Harish’s success goes to her

Lily, as I knew her, ever-smiling and charming with no ill-words for anyone, had a unique personality. She was a magnet that attracted and pulled everyone towards her. After the first meeting, one always wanted to meet her again. Having moved away from India soon after marriage, she did not have the opportunity to know various members of the family. Yet she attracted them and gained their confidence and affection. This speaks volumes about her. During my various interactions with her, I realised how she protected Harish from the worries of running a household and bringing up the daughters and their education so that he could pursue his love, mathematics. A fair part of the credit for his success goes to her. I recall her telling me, with emotion, about the publication of a part of his unpublished manuscripts taking shape and how she was awaiting the fifth volume of his work. I am so glad that she saw it in her lifetime.

After the first meeting, one always wanted to meet her again

Lily is gone. Her face will not be seen, her voice will not be heard but her memories will be cherished.

Kshama Suresh Chandra knew of Lily from the time of her marriage to Suresh in 1957. However, the two met each other only in 1987, and they developed a spontaneous and close bonding.

Charlotte Langlands

A woman of remarkable beauty, intelligence and grace, Lily had also an amazing gift for friendship.

Lily and I first met in Princeton during the 1960s at social gatherings of the mathematics community. In 1973 when my husband, Robert Langlands, became, through the suggestion of Harish-Chandra, a permanent member of the School of Mathematics of the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), Lily and I became neighbours and good friends. Although we had very different backgrounds, we still had much in common: husbands who were mathematicians, children of a similar age, an interest in the IAS community and in local and current events.

Lily was always well-informed and prepared for discussion

Lily’s “at home”-style tea parties to which I was often invited offered me the opportunity to make many new friends and to develop a deep appreciation for Lily’s easy conversational style and her genuine interest in her guests.

During more than 45 years of our friendship, Lily and I attended a wide variety of events together, sharing our thoughts on all manner of subjects. Lily was always well-informed and prepared for discussion, and often functioned as a sounding board for my less clearly thought-out ideas.

We served together on the Board of Trustees for Crossroad Nursery School and when I became chairperson of the Board, I asked Lily to be the secretary. I needed her knowledge and advice which she gave generously.

It is difficult for me to express clearly how great a loss I feel by the passing of Lily Chandra. During the many years as neighbours on Battle Road, I would telephone and suggest that we have lunch together at IAS or have tea in the afternoon at her house or mine. From those years, the fondest memories remain.

After Lily moved to “Windrows”, a retirement community, I naturally saw less of her. However, she made every effort to retain a connection with her many friends. We will all miss her.

Charlotte Langlands befriended Lily during their years of living in the neighbourhood of IAS, Princeton, which is where she presently lives with her mathematician husband Robert Langlands.

V.S. Varadarajan

I first met Lily in 1968 during my first of many visits. After Harish passed away we became closer. As my friend Shekhar said, she was a woman of strength and grace. She tried to see the good in everyone. Every year she would send a calendar to us, and our new year began only after we received it. Anytime we got a call beginning “This is Lily calling” in her beautifully accented voice was an exciting time.

She had a very wide circle of friends. Starting from Harish’s cremation when she consoled me, she allowed us the privilege of being close to her. In her own way she acquired a deeply philosophical view of life. Of her it can be truly said, echoing Lincoln, that she had malice towards none and charity for all. Her reading was eclectic, and what she read she made a part of her. She consoled in difficult times. She was intensely happy that some of Harish’s notes came out in a posthumous volume of his Collected Papers. For me her delight was the reward I wanted.

For us only tears are left. Whom can we blame? Why should a light, bright and shining be extinguished at its brightest?

Varadarajan sent these words as an e-mail to Premi, who read it at Lily’s funeral on 3 February 2019 on his request. He was hospitalised at the time but kindly asked to be represented.

Joy Mellor

I remember here the times spent, many years ago, with my lovely friend, Lily.

We first met at Bishop Cotton Girls’ High School in Bangalore, just as India was gaining her independence. Surprisingly, our paths did not cross earlier as we subsequently discovered that, as young children, we had both lived on Millers Road—she at the Indian Institute of Science, and I spending holidays at my grandparents’ old house, `Torquay Castle’! My uncle, the Indian classical dancer Ram Gopal, also spent time there.

Rev. Tom Mellor, my father, was appointed as Treasurer for the newly-established church in South India, formerly The Methodist Mission, so we lived in the city after returning from a year in the UK. School life loomed for me! Bishop Cotton Girls’ High School was chosen and I met Lily.

Lily was tall and elegant, had a fine sense of humour, and she spoke fluent French, of which the other girls and I were terribly envious! She conversed with her parents in French. Our Headmistress, Miss Hardy, insisted that Standard IX girls should be able to make polite conversation in French with each other during the French lessons—agonising for everyone, except Lily. Neither of us were keen on sports so we had that in common—all that running and jumping in the heat of the day!

Her battles with learning to ride a heavy men’s bicycle mirrored my attempts at about the same age, but we never encountered each other around Millers Road. Girls in those days led very sheltered lives—Lily cycled in the grounds of the Institute whilst I peddled around my grandparents’ garden.

We did, however, spend a very happy holiday together, with our respective parents and not forgetting her little dog, Fifi, in the Nilgiri Hills—Ooty then was still a quiet, peaceful place.

She married young. She always said she knew she was destined to marry Harish—they made a perfect couple.

The last time we met was in London in 1973 when Harish was awarded the FRS. My husband, Leslie Jones, a Welsh artist and educationalist, was with me. Years later, their two daughters, Premi and Dini, stayed with us in our home in Colwyn Bay, North Wales.

Lily and I never managed to meet up again, but I used to look forward to receiving her letters sent by Aerogram, the tell-tale blue envelopes bringing much welcome news about her family life in America.

She always said she knew she was destined to marry Harish

I often recall many happy times together with Lily in Bangalore, Mysore and Ooty. So much changes, but recalling early friends brings warmth to one’s heart.

Joy Mellor is a childhood friend of Lily’s from their school years in Bangalore. She now lives in London.

Lakshmi Pratap (née Ananthasayanan)

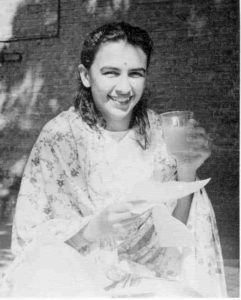

A few weeks after my third birthday I was enrolled in the first class of my school in Bangalore. I was sent out by my mother then in the throes of morning sickness unable to bear the presence of a troublesome child. I do not remember how I navigated my first or second year of school but I do have clear memories of some events in my third year of school. One of them was the arrival of a new girl sometime after the start of the school year. She was a head taller than the rest of us with lovely naturally curly hair, and very quiet. A little later there was a whisper amongst us that she spoke no English and was fluent in French. Eventually we learnt that she did speak English besides French, and I was pleased that the French nuns could no longer speak about us freely in French in our presence.

This was the start of my association with Lily which lasted through eight years of school. She caught my attention when she soon was the head of our class in studies, and she maintained that lead during these years we were together. I remember trailing the pack for some years, then caught up with the cluster of four or five girls who headed the class year after year. Lily was not only tall and beautiful, she was the top student in the class, never got into any kind of trouble, and calmly accepted the fact that we compared her to Elizabeth Taylor—except with brown eyes. She was confident and comfortable with her classmates and never a showoff. She had no special friend in school; though I was surprised that over the years she invited me to spend a few Saturdays with her at home. I remember two visits; one where she encouraged friends to bounce a tennis ball off a door at her home instead of the wall and then run and hide, this was to tease the person on the other side of the door called Harish-Chandra. This game was boring to us and we tired of it soon. The other visit happened to be the day she got her own bicycle, she brought the new bike to show it to all her friends, and graciously let everyone who could ride one a turn on it around the road that circled the wide open grounds of the Institute. I was so happy that evening when we all trooped to her home at dusk. This was the first time I did not have to beg someone for a few minutes on a proper lady’s bike.

The years went by and it was 1948, the year we would take our middle school exam with all the other middle schoolers in the English medium system in Bangalore. We were absolutely certain that at last there was a girl who could match the boys who topped the list. Alas her name did not appear amongst the top five; and I remember the discussion at my home about this, if only Lily had the quality of math teachers the boys had, she could have easily been the first. Well we consoled ourselves with the thought that she would have another crack at the first rank two years later when we wrote our finals.

It was a shock to all of us when Lily and all the other children from the Institute had to move to another school, which provided transportation for them, since the Institute had discontinued the bus service. She had been the leader of the top cluster of girls in every class and I missed her presence, she set the pace and I for one always tried to catch up. We got snippets of how she was doing in the new school and when the results of our final exam were published eagerly scanned the list of top candidates, hoping she would be the girl to outrank those boys.

Soon Lily would leave Bangalore and move to Mysore with her parents, but before that move there was the Indian Science Congress and Lily asked me to be one of the volunteers helping out with some odd jobs. I hardly had anything to do but watched with fascination how confidently Lily moved amongst the top scientists of the day. She seemed to know so many of them, they smiled and often waved to her, and I believed this was the start of the makings of another great woman scientist.

We never kept in touch with each other after she moved to another school or when she moved to Mysore, so it was another shocker to receive the invitation to her wedding to Dr. Harish-Chandra. She was a beautiful bride and they were a lovely couple. The story of how she swept him off his feet, his proposal, their wedding and how they went off to the USA was one that oft-repeated amongst her schoolmates of the early years.

Lily’s parents were good friends of one of my uncles, who lived next door to us, and Mrs. Kale always stopped by to see us when she visited my uncle and family. By this time I also realized that all the past invitations to spend a day, volunteer, and attend her wedding were probably due to her mother’s promptings. I will always remember the warmth and graciousness with which she included me in her special circle of friends at the Institute.

Whenever Mrs. Kale visited she had photographs of Lily and a bit of news about her. After Mrs. Kale moved to the US, our teacher Mother Marguerite de Jesus, who heard from Lily regularly, shared some news. After I moved to Ohio, I always visited Mother M. during my visits to Bangalore and she would encourage me to get in touch with Lily and gave me her telephone numbers.

Finally it was in 1986 or 1987 I called Lily and continued our tele-conversations for a couple of years. We discovered our children shared the same birth years, that we were both widowed the same year, and besides chatting about common friends and our early years we also discussed books. Then it was November 1989 when I visited Princeton on Thanksgiving day which was also Lily’s birthday. I was warmly received by her and the tele-conversations after this meeting were not just to wish each other on our birthdays, but also about her visits to India, my extended family in India, news of our schoolmates, books and music.

I looked forward to hearing her views about a particular author or book, and saved up items for our chat. I was eager to share the memoir of Vasu Varadhan who is married to the mathematician Varadhan and lives in New York City.

Last year when I called and left a message on Lily’s birthday, she did acknowledge it, until two weeks later, when she called to wish me, saying she would call again for one of our long chats. It was our last.

Lakshmi Pratap now lives in Dallas, Texas where she enjoys both professional and civil activities. A childhood friend of Lily, she gave her news of Bangalore, the memories of which Lily fondly cherished.

Vijaya Ramachandran

Lily Harish-Chandra was a lovely and generous person whom I have had the privilege of knowing from the time I went to study at Princeton University many years ago. At that time, I was fortunate to have had an introduction to the Harish-Chandra family, and Lily wrapped me in her warm welcome soon after I arrived and all through my four years at Princeton. I went to the Harish-Chandras’ for Thanksgiving and many other occasions. Having Premi and Dini there cemented my connection with the Harish-Chandras, and of course, I had a deep respect for Harish-Chandra’s distinction and eminence.

Lily was a many-faceted person. She was the perfect hostess for the large Thanksgiving meals that must have taken no small amount of effort to prepare and set up, and yet seemed so effortless. She was also a genuinely warm and friendly person with whom I kept a lifelong connection. There was always that unmistakable warm smile, but behind that smile, there was a genuine connection. After I left Princeton I would see her occasionally when I made short work-related trips to Princeton, and it was quite amazing to me that Lily, in spite of her extensive collection of friends and acquaintances and the length of time between our meetings, remembered so much about me.

There was always that unmistakable warm smile, but behind that smile, there was a genuine connection

Lily was a thoughtful and modern woman who supported and encouraged independent women like me in her own effortless style. I came to Princeton at a time when not many Indian women came on their own to the US for graduate studies. Outside of fellow students, most of the Indians I met there did not know what to do with me once they discovered that I was on my own at Princeton. Not so with Lily. I had easy and comfortable interactions with her and she was fully accepting of my deep involvement in my graduate research. Not only accepting of it, but she talked to me on and off about how I liked my research and my plans for my future career. These were natural, friendly discussions and at that time did not surprise me. I thought it came naturally with Lily’s warm personality. Discussing this recently with Dini [Devaki Chandra], I realize that it must have taken contemplation and independent thinking on Lily’s part to understand and accept a person like me who grew up in India, as she did, and then took a path that was not quite the traditional path.

Lily was very happy for me when she heard that I was joining the faculty of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign after graduating from Princeton. I fondly remember her giving me the book Princeton Reflections (Contemplations in Color), as a gift to help me remember Princeton, once I moved on to a new place with an actual job.

After graduating from Princeton I saw Lily only occasionally when my work would bring me back to Princeton. I would call Lily to see if I could stop by when I came to Princeton, and she would always make the time to meet me, and we would have a nice chat and catch up with news at both ends over a cup of tea. I even recall a time when I came to ETS (Educational Testing Service) in Princeton for a couple of days for setting questions for the GRE exam. The work there lasted from right after breakfast to late in the evening, so I called Lily and told her that this time, unfortunately, I could not stop by to visit her since the only time I had to myself was breakfast at ETS and couldn’t expect her to come and join me. Sure enough, she did! We had a delightful meeting over breakfast.

The last time I met Lily was in 2012, shortly before she moved out to Windrows Drive. I was visiting Princeton University for a couple of days and I called her as usual. And sure enough it resulted in a warm invitation to visit and we spent the evening chatting. It was bitter-sweet since I knew I would never meet her in those familiar surroundings on Battle Road. She was a little quieter than I had known her in the past, a bit wistful, but who wouldn’t be when they are about to leave the house they had lived in for many decades and built a family and a life? But that was just in passing, and she was very much the Lily I had known, and she quickly moved on to talk about her enthusiasm for the more compact and manageable place she was moving to. I had hoped to visit her at her new place but that was not to be. I cherish the many good memories I have of her, and will always remember her generous spirit and her joy for life.

Vijaya Ramachandran met Lily during the years of her PhD at Princeton University. She is now a professor of computer science at the University of Texas at Austin.

Dominique Borel

Lily lived in the house next to ours for over 50 years. Almost daily, throughout my childhood and beyond, one or all of us traipsed back-and-forth through our linked back yards. When not just cutting through to catch the school bus or run some errand, we stopped by for tea, a chat, a meal, to bring or borrow something, share a drop or more of gossip or news, play, and for countless other neighbourly and friendly exchanges. I remember my mother coming home from Lily’s and announcing to my father that Lily was expecting another child. That would be Dini. My mom, Gaby, and Lily shared, almost daily and often more, their experiences across the garden gate, which saw them through a myriad of light-hearted as well as cataclysmic life events.

A lively conversant, whether it was on the phone or in person, if one embarked on a conversation with Lily Harish-Chandra, we knew it wouldn’t be for five minutes. Interested in a multitude of subjects and what one and others were up to (I’m credited in early adolescence with having introduced Lily to the Beatles and Rock and Roll), one knew one was to cover a lot of ground. When I returned from India, intoxicated with my first trip there—after having been invited for the official opening of the Chennai Mathematical Institute and to honour my father recently passed—I raced over to Lily’s the first chance I had, eager to share every detail of the people, culture and profound beauty of the country I had fallen in love with. Lily did not disappoint. She hung on to my every word and had much to contribute. It was a wonderful afternoon.

One day Lily laughingly recounted her US citizenship interview to me. After conscientiously studying and passing the written exam, she went well-prepared to take the oral exam which was, at that time, the final step towards citizenship. The immigration officers must have been quite taken with her—young, lovely and beautifully wrapped in a sari—and have been eager to expedite her citizenship. They asked her two questions: What were the colours of the American flag and who was the first president of the United States!

She knew exactly how to target the right gift for the right individual and took rare pleasure in it

As many of us have reminisced, Lily was an extraordinary gift giver. She knew exactly how to target the right gift for the right individual and took rare pleasure in it. When I was in junior high school, we had, as girls did automatically then, a home economics class which concentrated mostly on sewing. My friends and I became enamoured with making our own dresses. Lily found and gave me material that was age- and trend-perfect. I still have the dress. A few years later, when I was in high school, she saw how passionate I was about theatre and gave me a book on theatre history, which sits on my shelf today and that I still occasionally consult. My mother’s house holds many Lily gifts, each of them touchingly personal: A porcelain elephant teapot, whose trunk serves as a spout, is a wink to the India my parents adored, and a clock in the kitchen, decorated with facsimile slices of pies and cakes indicating the hour, is a tip of Lily’s hat to Gaby’s pie-making talents as well. When my father, Armand, died, Lily, having gone through the process years before, gave my mother a paper shredder. Her last gift to us was a lovely speckled Poinsettia at Christmas. Despite our family not holding the record for the neighbourhood green thumb, Lily’s plant continues to thrive.

Lily was a steady and intensely loyal person to have the good fortune of counting in one’s life. I will and do miss her.

Dominique Borel is the daughter of Armand and Gaby Borel, who were close family friends of, and lived next-door to, Lily and Harish-Chandra at IAS in Princeton for over 50 years. She now lives in New York City where she works in theatre as an actor and artistic director and, currently, also works as a French/English interpreter.

Indu Prasad

We first met Harish-Chandra family in September of 1973 at the Institute for Advanced Study at a newcomer’s reception (and later at a party at Marston Morse’s house for visiting mathematicians). Lily was clad in a beautiful sari and a big smile. She invited us for tea at her house the very next week. This first meeting developed into a lifetime of friendship with her family. Whenever we were in Princeton we were included in her grand Thanksgiving dinners at her home with several generations of Harish-Chandra’s extended family. She was the only child of her Indian father Mr. Kale, and her Polish mother who later became Harish-Chandra’s French teacher, and that was the time he met Lily.

Thanksgiving dinner at the Harish-Chandra home was full of interesting conversations, discussions, laughter and of course delicious festive dinner. We were regularly invited by Lily even after Harish-Chandra prematurely passed away in 1983.

We were often included in tea parties at her home and her mother Mrs. Kale joined us and contributed to the discussions. At one of these parties during 1980–81 my son Anoop was sitting next to Mrs. Kale and she talked to him the entire time, about her life in Europe and the turbulent times during the Second World War and how she and Mr. Kale managed to come back to India from Europe. Anoop was thrilled and became so interested in her narration that she took him to her room, continued her life story and very proudly showed him a painting done by Harish-Chandra for her that was hanging in her room. That conversation made a deep impression on Anoop and aroused his interest in history and lives of people affected by wars and other calamities.

Lily’s annual Thanksgiving dinners continued at her home until her knees became too painful but she remained the matriarch of Harish-Chandra’s extended family living on the east coast of the United States. A nephew of Harish-Chandra took over this annual tradition and Lily looked forward to this big event every year, hiring a driver to drive her to Roosevelt Island in East River, New York, where three or four generations of the Chandra family gathered, and it gave her immense pleasure seeing them all.

She was very compassionate and helpful to her seniors and those who needed help. She did errands, kept accounts for them, arranged doctor’s appointments and drove them to the clinic, etc, and even took them for outings. She also made efforts to bring Indian women in the Princeton area together by organizing lunches at her home, and also smaller gatherings for tea at the home of Kusum Dixit (a friend of hers). She continued to host friends and relatives at her retirement home at Windrows.

Finally, I would like to recount an incident which shows her skill at arranging things. In 2003, Gopal [Prasad] wished to meet Armand Borel who was terminally ill, but since chemotherapy had made him very weak he was reluctant to meet people. During my phone conversations with Lily, she said it will be easy for her to arrange a meeting which will look unplanned and very casual. She invited Gopal, me and Mrs. Borel for an early dinner at her home and, naturally, Gopal asked Mrs. Borel about Armand. Immediately and spontaneously Gaby offered, “Come with me to my house next-door, Armand will be very happy to see you.” Gopal went with her, saw Armand and chatted with him for over an hour; it was a very pleasant meeting. The next day, quite early in the morning, we got the sad news of his passing away from Lily.

Indu Prasad first met Lily and Harish-Chandra and their two daughters during her first year-long visit to Princeton in 1973–74. Since then they shared a close bond of friendship. She lives in Ann Arbor and Princeton with her husband Gopal Prasad who is Professor Emeritus at the University of Michigan.

Ramaa Raghunathan

My meetings with Lalitha Harish-Chandra—Lily, as she is known to family and friends—have been only three.

The first was when she came to Bombay to look at the bust of Harish-Chandra being made, to be installed in the then Mehta Research Institute in Allahabad, in time for Harish’s 70th birthday in October 1993. We made several visits to the studio of the sculptor who was working on it from the many photographs she had sent earlier. She was charmed by the Tata Institute [TIFR], the building, the incomparable collection of modern Indian art, the beautifully landscaped garden with its vast lawn and the wide-open vista of the sea. She had a minor adventure with her return flight cancelled and our desperate efforts to find another one.

Then the second time was when she went to Allahabad for the unveiling of the bust where all the guests were hosted and royally entertained by the Director H.S. Mani. Her elder daughter Premi [Premala Chandra] and John Kuriyan, the husband of her second daughter Dini, had come from the US with her, and Harish’s brother Suresh Chandra and his wife Kshama from New Delhi were also there; so it was a family get-together as well, with some cousins in Allahabad. We visited the University of Allahabad where Harish had studied and saw the Muir Hostel where he had stayed. It was somewhat saddening to see the campus with its neglected buildings. The corridors of the Physics Department where Harish must have paced up and down talking with the renowned physicist Dr. K.S. Krishnan were no exception. A peep through the broken glass doors of the convocation hall revealed its derelict condition. But then we met a bunch of hostelites who came eagerly—with shining idealism in their faces and stars in their eyes—to meet Mrs. Harish-Chandra, hardly believing their good fortune.

She has been one of the most—even the most—gracious and heart-warming presence

The last time we met was when my husband M.S. Raghunathan and I visited her in her lovely home in Princeton in 1997. She has been one of the most—even the most—gracious and heart-warming presence in my life. I am sure that is the effect she had on everyone who came close to her, but one tends to think that one had somehow a special place in her life. We marvelled at how we took to each other from the word `go’; and how our views and tastes on many things, especially books, coincided tunefully. We kept in touch over the years, corresponding, exchanging books and making occasional but very long calls to each other when she would update me on her girls and their kids—and so somehow the separation through distance did not seem to matter. Unfortunately, the last few years, the contacts have been far and few between, especially after she moved from her home to an assisted facility. She called to explain to me what made her finally decide on it: after a knee surgery, her mobility had become somewhat restricted. We had a long discussion on it and on the politics in India and the US (getting indignant over the same issues as usual!) and so on. Somehow I could never reach her by phone in the new setup, but we continued to remain in contact through e-mail.

When I lost my mother Lily had written to me that “the time of passing is never right” and it is not now

It has been mentioned in articles about Harish-Chandra how he married in December 1952 in Mysore, Lalitha Kale, daughter of Dr. G.T. Kale, a botanist, and his Polish wife. At that time, a Khatri from UP (Uttar Pradesh) marrying a Maharashtrian was outrageous enough and that too born to a foreigner! But Lily was gladly accepted, as the family had given up hopes of the almost-thirty Harish ever marrying and they were relieved that he finally brought a bride home, civil ceremony notwithstanding. And Lily was no stranger: Mrs. H. Kale had been Harish’s French teacher in Allahabad and he “copied”, as an eighteen-year-old in a gesture of affection and gratitude to a favourite teacher, Peter Paul Rubens’ ‘Le Chapeau de Paille’, with its appealing title in French. When I visited Lily in her Princeton home, one of the first things I asked for was to see that painting which had pride of place on their wall. When Harish first went to Bangalore, he lodged with the Kales who had also moved there earlier. To ten-year-old Lily, his serious absorption in science was a source of merriment and along with her friends she used to play pranks, trying to distract him while he wanted to be left alone to work. When he returned on a visit to the TIFR in Bombay during 1952–53, Lily, “now a strikingly beautiful young woman”, became his wife. (It is said that he proposed to her by sending her a telegram! I did ask Lily about it and she confirmed it.)

One of the anecdotes Lily used to tell me is about a nursery school in Princeton where the progeny of the outstanding bunch of scientists and thinkers adorning the faculty of the Institute go to begin their formative years of schooling. The record of the behaviour of these children itself will, no doubt, make an interesting sociological study. You will find a toddler going back and forth with knitted brows and his hands clasped behind—and if interrupted by an importunate playmate, would loftily gaze down at him as though descending from the heights of science to mundane matters and lisp “Don’t talk to me. I am thinking.’’ It was here that one teacher overheard a little girl inviting a boy to “play house”’ with the suggestion, “now you be the father and grumble about something and I’ll be the mother and pay no attention”. That day when Lily went to pick up daughter Premi (now Dr. Premala Chandra, a solid-state physicist), the teacher said, with a twinkle in the eyes, to the embarrassed mother, “now we know how your household runs!’’

I have been looking through our correspondence over the years, and our discussions come alive, and I seem to see her smiling face and affectionate look and again recall our take on books. I do not remember to how many people I have recommended one of the books she sent me, The Arrow of the Blue-skinned God by Jonah Blank, his retracing of the route Rama took from Ayodhya to Lanka. In Absolute Zero Gravity, a book of light-hearted anecdotes about the Institute in Princeton, Raghu and I were amused to find one about Raghu! The name was not mentioned and they had made him a professor from Harvard, I think. Lily had not known about this and entirely by chance she had sent the slim volume, correctly thinking that we would find it amusing in general.

When I lost my mother in July 2013, Lily had written to me that “the time of passing is never right” and it is not now. I feel privileged and happy that we got to know her and can think of ourselves as belonging to the charmed circle of her friends. Lovely memories last forever and hence, so will all our memories of Lily.

Ramaa Raghunathan lives in Mumbai with her mathematician husband M.S. Raghunathan. Her warm friendship with Lily blossomed from the time she visited India in 1993, in connection with the making of the bust of Harish-Chandra and later at its inauguration.

Footnotes

- A game-theoretic problem introduced by A. Tucker, where two prisoners A and B, not allowed to communicate with each other, are offered parole if they implicate the other. If neither is implicated, both receive a normal sentence, whereas the implicated one’s sentence is harsh. The dilemma arises from the lack of knowledge of the other’s decision. ↩

- See the article “ Childhood Memories ” in this issue of Bhāvanā. ↩

- Premi’s husband Piers Coleman is a distinguished professor of physics at Rutgers University. ↩