It is a little over one year since the passing away of Padma Vibhushan Professor Roddam Narasimha on 14 December 2020. Bhāvanā team reminisce here about their interactions during several of their meetings with him in connection with his articles in Bhāvanā.

Roddam Narasimha, fondly known as RN, represented what is possible when deep scholarship, combined with a swathe of interests, is founded on an unflinching commitment to rigour. His combination of interests was unique, and opened up a set of possibilities that, with his passing away, stand diminished. Aerospace engineering, fluid dynamics, meteorology, parallel computing, history and philosophy of Indic science — all these held his interest. These were not unrelated interests though, and did not develop accidentally. His early interest in boundary layers transitioned smoothly into a study of the monsoon. Perhaps it was vice versa, given his lifelong fascination with clouds. He could not only talk about the long history of research on fluid turbulence, including his own work in it, but was also equally at ease talking consummately about quantum mechanics, and the history (and the historiography) of science. Such a description of his areas of interest, however, does not even begin to speak of the man and his rare scholarship.

While at the Indian Institute of Science, his efforts with the Monsoon Boundary Layer Experiment (MOBLE) and the Monsoon Trough Boundary Layer Experiment (MONTBLEX), and his role in founding the Centre for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, were pioneering. The Light Combat Aircraft (LCA), including its key operational specifications, was his brainchild. His interest in the history of science – whether ancient or more recent, such as in Mysore Rockets – and his commitment to facts was exemplary.

When he was the director at the National Aerospace Laboratories, he had a tradition of giving eagerly awaited lectures on his birthday, every year. He was a skilled raconteur with a phenomenal memory for the smallest of details. There was the story of Satish Dhawan advising him to go to Caltech, which he did, and he arrived at Pasadena as “Satish’s boy”. This was a story he narrated with a glow of pride not visible at other times. He could talk about Dhawan for days. Then there was his bet with friends at Caltech who had wagered that he would return to the US no sooner than he had flown back to India, after earning his PhD. There was the story of his trip with his student K.R. Sreenivasan to measure the sonic booms from the Concorde, so that the government of India could then decide if the supersonic aircraft could be given approval to fly over Indian land. (It wasn’t approved!) There was the story of how he met the Japanese fluid dynamicist Hiroshi Sato so often at conferences in the US, that he wondered why they shouldn’t be meeting in Asia instead, thus founding the Asian Congress of Fluid Mechanics. Over time spent with him in his office, at his home, or when travelling together in a car, these and many other stories organically became your own, stories that you later told others, stories that you felt you had somehow participated in, and which had grown to become an indelible part of a collective memory. And in all these interactions, and always, he was careful to never say anything unkind about anyone, even “off the record”.

For a man of such humility and accomplishment, and decorated with some of the highest honours in science and engineering, he was remarkably self-effacing and unassuming. We were always welcome at his warm home, even on short notice. No hint was ever given of the work that he had to put aside to spend time with us. Proofs of an article sent to him would come back with the full range of copyediting marks, neat scribbles on the margins, additions and deletions, all to ensure that each statement had been accurately weighed, and perfectly nuanced. Only to be patiently followed by more rounds of the same, until he was fully certain that everything was accurately worded.

Even as the thought of engaging RN in a free-wheeling conversation with Bhāvanā was in the offing, fortuitously for us, it so turned out that he was invited to receive a special honour at a conference in Banaras Hindu University [BHU], during December 2016, held under the auspices of The [Indian] Mathematics Consortium, and jointly organised with the American Mathematical Society. It was also the same conference in which the inaugural issue of Bhāvanā was to be released. To our immense delight, the team flew with him from Bengaluru to Banaras for the conference. He was, quite simply, a very charming company and the big age gap of over three to four decades between us and him, was never felt during our entire journey. Even the informal conversations we had with him then, would now in itself easily translate to be an article, or even two, if only we had recorded it in full. One of us, Nithyanand Rao, luckily recorded some parts of this interaction on a cell phone, even while all of us were huddled around him in rapt attention, listening to him in a bus going from the Banaras airport to BHU.

Thus it was a little later in early January 2017, that we were invited to his home for a leisurely Sunday evening conversation, and which turned out to be the first among several eminently engaging meetings later with him. The passage of time was barely felt, and it was very soon close to three hours, by when it became clear that we had to come back for a second session. The sheer expanse of things that came up in the first conversation left us on such a high that, as we left his home, we were possibly even unmindful of the terrain we were walking on. A truly elevating, and intellectually levitating experience!

As our interactions became frequent and regular, and while we worked on editing the transcript of this first session, certain key aspects in the persona of RN became quickly evident to us — impeccable factual correctness, always backed by authentic records, and most often from the very root source; not doing things in haste, but giving them the time they deserved; encouraging, pleasant and yet gently firm, and crystal clear in disposition. Once he was committed to a cause, you knew that the eventual result would be worth the wait, with truly enriching insights he would come up with. The actual conversations carried many interesting details, anecdotes, and yet always possessed a rare gravitas, so characteristic of interactions with RN. One of the first instances when all of the above traits were revealed at once was during the first part of the interview that our team did, in January 2017, in the warmth of his home. Talking about the glorious days of the princely Mysore State during the reign of the Wodeyars, RN was contrasting the quality of governance that existed in the princely Mysore state, against the governance of territories outside its borders, which then naturally fell under the British Raj. He was recounting the stark difference in quality of governance as seen and experienced by his paternal grandmother, and from whom he had heard of this gubernatorial difference. RN corroborated this fact by recalling the words of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who during that time was the lawyer who had argued in favour of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, as Tilak had then been charged by the British, in a sedition case. At the time of editing our article, given the perennial interest and relevance of such an interesting fact of history, we asked him for a source that can be mentioned, and to which our readers could turn to, in order to verify it for themselves. RN mentioned reading about it in an article by Khushwant Singh, but could not lay his hands on the exact document, even after a month or so. So we explored a bit, and asked around to learn that there was a book by A.G. Noorani, published by the Oxford University Press, and curiously titled `Jinnah and Tilak: Comrades in the Freedom Struggle’. We were fortunate to find it in an online store and bought it, hungrily leafing through the pages until we found the precise information we were looking for. RN’s recollection was spot on, and he was very happy that we did manage to find an authentic source that backed up his particular recollection.

A similar occasion was when he quoted Āryabhaṭa, and when we wanted to mention the source—he readily brought out the photocopied version of a book, and read out the original Sanskrit shloka from Āryabhaṭīya. Such was his scholarship and strict adherence to authenticity, placed firmly as it was, in the finest traditions of scientific research. Moreover, the facility with which he could spontaneously converse at different levels of exposition and rigor meant that these remarkable traits were ingrained in him from a very young age, and perfected over time as he grew to be a seasoned academician.

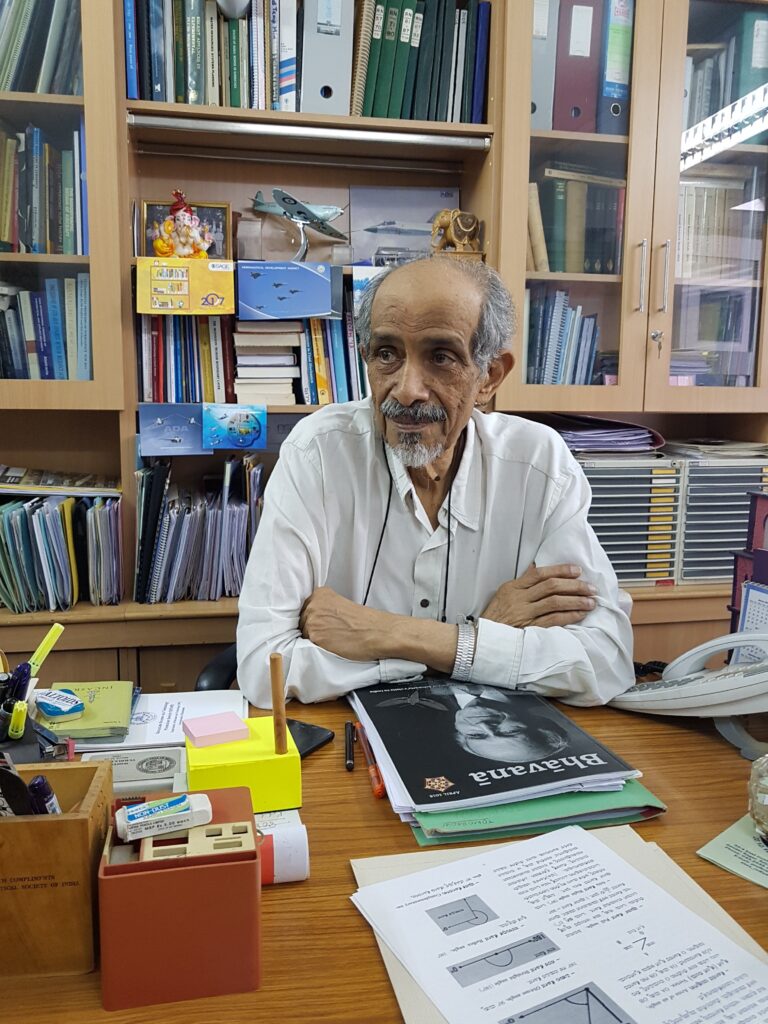

For those who visited him in his office in Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR), it was clearly visible that he treated everyone, including the gardeners, the cleaning / housekeeping staff, workers in the canteen, with warmth and affection. This was another side of the man, completely at ease, respectful and cheerful in social settings.

Given his abundant knowledge and great enthusiasm, he had promised to write more, and would have indeed written too, for Bhāvanā or elsewhere. One thing that came up a couple of times in our conversations was about the famous theorem of Pythagoras. He talked about the work of a German scholar undertaking a deep study of attributions and stories surrounding Pythagoras, and mentioned the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy to be a reliable source to find all its well documented details. The summary in short, quoted directly from this source, is that Pythagoras wrote nothing, nor were there any detailed accounts of his thought written by contemporaries. By the first centuries BCE, moreover, it became fashionable to present Pythagoras in a largely unhistorical fashion as a semi-divine figure, who originated all that was true in the Greek philosophical tradition, including many of Plato’s and Aristotle’s mature ideas. A number of treatises were forged in the name of Pythagoras and other Pythagoreans in order to support this view. There is evidence that he[Pythagoras] valued relationships between numbers such as those embodied in the so-called Pythagorean theorem, though it is not likely that he proved the theorem.

For a man who held India and its holistic welfare very close to his heart, it was inevitable that he would find himself right in the centre of matters of strategic consequence. India’s defense security, and her territorial integrity obviously weighed at the top of his priorities, as evident in the pioneering role he played in putting together the operating specifications, and the design parameters for India’s very first indigeneous fighter aircraft, popularly known as the LCA (Light Combat Aircraft). For someone who learnt his art from another towering Indian whose own love for his country is well documented, it surprised nobody that RN chose the title “A Real Patriot” when it was time to pay his respects to his guru, Satish Dhawan, on the occasion of the latter’s birth centenary in September 2020. As it turned out, within weeks of RN’s passing away, the Government of India, in early 2021, ordered a total of 83 LCA (named Tejas) for procurement from HAL, in an unprecedented deal worth Rs. 48, 000 Crores (upwards of 6 Billion USD). It was also a fitting tribute to a young dreamer whose love affair with flying metallic birds had begun with the serendipitous spotting of a Spitfire fighter aircraft displayed on the lawns of the Aerospace Engineering Department of IISc, seventy odd years ago. RN would have characteristically cleared his throat in approval at the welcome turn of events, and beamed a radiant smile.

The sheer breadth of RN’s intellect posed a serious problem of plenty for us. Our two-part interview of him alone would have exceeded the length of a typical issue of our magazine. Yet there is much we couldn’t document in depth—his founding of the Center for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, his tenure as Director at the National Aerospace Laboratories, and the National Institute of Advanced Studies, and his experiences while serving on the Indian Space Commission. Few in India have so adroitly juggled commitments to research, teaching, administration and public service for so long. Along with his deep and long-held interests in ancient Indian mathematics, history and philosophy, Roddam Narasimha represented the best of that rarified breed of the Renaissance Man. \blacksquare