With the passing of Professor Rohini Godbole on October 25, 2024, India has lost one of its leading scientists. She was a theoretical physicist who researched phenomena that are observed at high-energy elementary particle accelerators. The goal of this enterprise is to understand one of the deepest mysteries of nature – the ultimate constituents of matter. She had an enviable international reputation in the field and even helped to shape the plans for future billion-dollar accelerator facilities through her research. And beyond her research she was a passionate proponent of the scientific enterprise, an outstanding teacher and mentor of students, an active member of policy-making committees and an advocate for gender equity and the cause of women in science. She was also a close personal friend of mine for nearly 50 years.

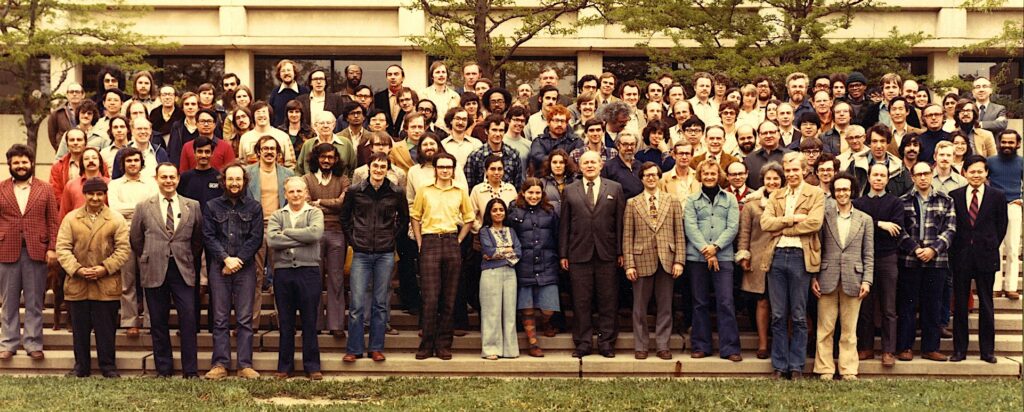

At Stony Brook University, where she joined the PhD programme in 1974, Rohini was an outstanding student and completed an excellent thesis. She was kind and hospitable to the Indian students who joined after her (including myself, as I joined in 1976). Some of the other Indian seniors used to be arrogant and condescending – I recall one of them assuring me I had little chance of success in academics! Rohini was the exact opposite, handing out both encouragement and advice to us along with generous hospitality. She invited some of us to dinner a few days after we joined. We were thrilled, as it was to be our first Indian meal at Stony Brook. The dinner was delicious but intensely spicy, and left us in tears, for she had mistakenly added a double dose of chilly powder. For years after that, I would cheerfully tell colleagues – in her presence – that she had tried to poison the new Indian students! This would be met with a fierce glare, followed by a smile. She knew it was meant as a compliment and an expression of friendship. All her life, she was never offended by any sort of joke or rude remark as long as the warm intention behind it was clear to her.

After her PhD Rohini returned to India, worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) for three years, and then went on to become a faculty member at the Department of Physics of the University of Bombay (now University of Mumbai). It was the start of her career as an independent researcher but there were two obstacles. On one side TIFR, where she found good collaborators, was not sufficiently convinced of her excellence to offer her a permanent position. On the other hand the University of Bombay, which gave her a position, expected her to teach but did not particularly care whether she did research (apart from one supportive senior mentor to whom she remained grateful for the rest of her life). She was destined for excellence, but to achieve this she had to maintain two centres of activity in Mumbai, separated by a gruelling local train ride, each of which offered her one of the things she needed to thrive. She would fulfil her teaching duties in the morning half, then travel to TIFR ready to interact and work on research projects – but in an informal capacity where she was not provided any office space or support. She would return home late at night, or sometimes stay over with friends at TIFR. A lesser mortal would have found the experience too taxing, but she kept this up with regularity for several years. By this time I was a junior faculty member at TIFR and we would often eat dinner together, along with students, in TIFR’s East Canteen.

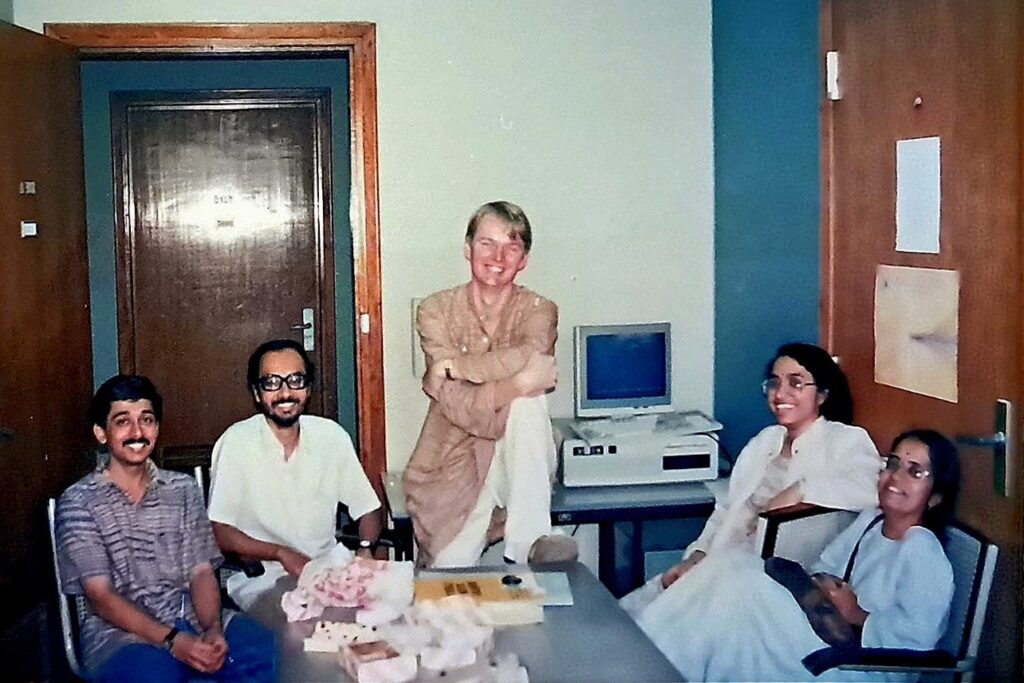

In 1986 she received two years’ visiting position at Dortmund University where, in collaboration with a young Postdoctoral Fellow, Manuel Drees, she worked on a series of papers that was to have a significant impact on the field. This, along with her work in many other areas of particle physics, propelled her to international renown. Her research profile steadily grew and in time the entire high-energy physics community at major European institutions (including the CERN1 laboratory) came to know and respect her. Soon she was being invited to sit on high-level committees to study\break the prospects and design of future particle accelerators, particularly a new generation electron-positron collider. This has not yet come to fruition, but if and when it does, her contributions will have been important – even though sadly she will not be around to see the results.

|

|

| Rohini Godbole and Manuel Drees speaking at the Kaoru Hagiwara fest at the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe in Kashiwa, Japan. Tao Han | |

In 1995 Rohini was appointed a faculty member at the prestigious Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore and this brought an end to the stressful phase of commuting between two Mumbai institutions. Her reputation ensured that she was enormously in demand at international meetings and conferences. She spent months as Visiting Professor at leading universities like CERN and the universities of Amsterdam and Utrecht, where her talks and lectures were greatly appreciated. She travelled often and enjoyed this immensely. I started the joke that she visited India only on Wednesdays – one more rude remark that would be met with a glare and then a peal of laughter. She also pushed for major international conferences to be held in India, and on many occasions we ended up together on the organising committee of these conferences, to which she brought her characteristic energy and determination.

Acknowledgements We record our deep gratitude to Manuel Drees, Niranjan Joshi, Vibhawari Thakar and Xerxes Tata for their crucial and timely help arranging for the various photos used in the article.\blacksquare

Footnotes

- CERN is the acronym for “Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire”, or European Council for Nuclear Research. ↩