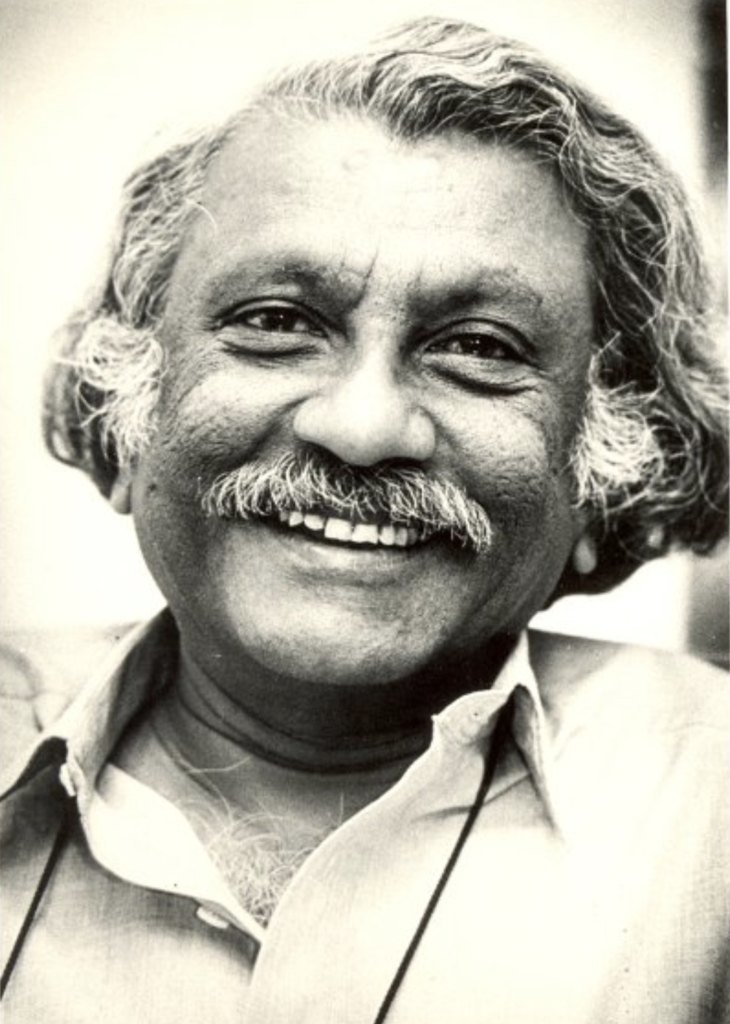

People who are remembered for doing things well pose a problem–-did they start out as they were or did they slowly become the person whom everyone remembers and respects? At some point in early adulthood, when we children left our parents’ home to pursue our own paths, we would get letters signed “Affly, Satish’’, so that’s what we, and his grandchildren, called him. As I grow older and encounter the inevitable failures in life and profession, I wonder: Satish always seemed to be so himself. Did he spring forth fully formed? Who was the pre-Satish?

This is a story of Satish Dhawan and some of the circumstances and people who shaped his life. I hope readers will be tolerant of the interspersed narrative approach, as I see his life with the clarity of hindsight, through the lens of my own interpretations and memories. I end with a meditation on the friendship of four scientists of the era.

“The least contaminated memory, might exist in the brain of a patient with amnesia— in the brain of someone who cannot contaminate it by remembering it.”1

Jyotsna Dhawan

June 2020, Hyderabad

Early Travels

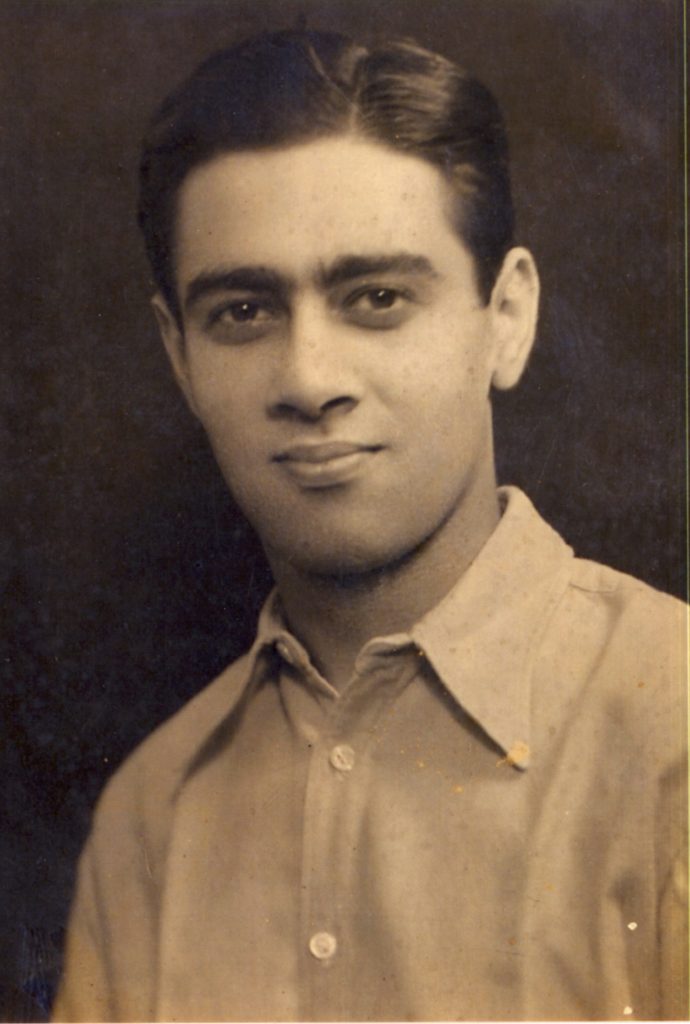

October 1944. Among the crowds arriving at Bangalore City Station is a young man from Lahore, come south for a practical training internship at HAL towards completing an engineering degree from the Panjab University. Hindustan Aircraft Ltd. (HAL, today Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd.) was started by the industrialist Seth Walchand Hirachand in 1940, but in a couple of years, is taken over by the war effort to create one of the largest operations in the East for repairing and overhauling British and American planes. The decisive role of the Royal Air Force fighters in the war has captured the imagination of the world. For an engineering student in the 1940s, flying machines represent what computing machines would become 50 years later–-the leading edge of some of the most exciting technical investigations and scientific discoveries. This young man is no different. He is eager for a chance to put his book-learning to use. Rooming in paying-guest accommodation near the Bangalore Cantonment, he learns quickly on the HAL shop floor, enjoying the opportunity to work on the aircraft engines and wings, and exhilarated by the concepts that underlie the ability of these substantial metallic structures to defy gravity. The principles of flight were no different from when the Wright brothers took wing four decades before, but the materials and their engineering were far advanced by the ‘40s. He wished he could fly one of those beautiful machines….

October 1945. As the world limps away from the soul-crushing ferocity of the world war, India is still engaged in her non-violent struggle for freedom from colonial oppression, for the right to reclaim a devalued history. A long road and many sacrifices have led here, and although many hurdles remain, it now seems that whether freedom would be gained is no longer a question of if but when. Among the more central plans for governance, there are already ideas forming for how independent India will build and strengthen its capabilities, including modern scientific institutions and industry. Some far-sighted individuals in government have formulated a program for educating young Indians in the best centres for technical and scientific education in the UK and USA [2]. A thousand scholarships are awarded to aspiring young Indians who are to become part of the generation that will build modern India. They will build with ambition and hard work, ideals and imagination. But they do not know now that this is who they will be, or indeed, that they will be remembered at all. Right now, an adventure awaits them.

At the Bombay docks, US troop-ships are thronging with ‘de-mobbed’ soldiers being ferried home from the China–Burma–India section of the Pacific Theatre, as part of Operation “Magic Carpet’’, organized by the US Army. Some civilians too are among the ship’s passengers, including our young engineer from Lahore, who is now bound for America to study aeronautics. Arriving in New York via Aden and Southampton, in a journey lasting about a month, the group of Indian students is settled into “I-House” (International House), a hostel started after the first world war, by those captains of industry, Rockefeller and Dodge. Started as a way to welcome foreign scholars and help them get accustomed to life in the USA, I-House has burgeoned into an organization that has had close to 100,000 alumni, many of whom have gone on to contribute to their home countries, retaining strong influences and friendships from their American sojourn.

In New York, young Satish finds that his admission to the California Institute of Technology has been deferred, as the aeronautics graduate program is yet to restart after the war. He is instead to report to the University of Minnesota (UMN). Minneapolis is not anyone’s imagination of California. It is cold and feels a bit remote, but everything is exciting to this 25-year-old. So, in addition to his Master’s course in Aeronautical Engineering, Satish finds plenty to keep him engaged, including several second-hand bookstores whose well-thumbed volumes, particularly of the inexpensive “Everyman” editions, which he transports with him from Minneapolis to California, and then all the way back to Bangalore when he finally makes his home there several years later. Among the biographies, philosophy, politics, plays and fiction that he accumulates during that year, a favourite book is a slim volume of the short stories of “Saki” (H.H. Munro), whose scathing indictments of English social snobbery are deftly delivered through the exploits of a subversive young dandy. These stories are set in “the golden afternoon” of the Empire, the years of peace before a generation was wiped out on the fields of Flanders. Years later, these anachronistic satires with their ability to reveal the ridiculous nature of class superiority become a favourite read-aloud for us all.

In reading the history of the University of Minnesota’s Department of Aeronautical Engineering and Mechanics, it appears that there was in the ‘40s an ongoing tension between those who wished to maintain a strong industry focus, perhaps a natural outcome of the recently concluded war, and those who believed in a more broad-based scientific enquiry as the platform for the graduate program. At this time, the Department built the Rosemount Aeronautical Laboratory whose hypersonic wind tunnels were also used by industry and the military. While the aeronautics students probably got an excellent hands-on experience in these high-tech facilities, there was a concern that they should be oriented more towards fundamental theories underlying those applications. A series of events led to that Department overhauling its research focus in the next few years. One driver of this vision is a movement sweeping many leading aeronautics departments such as Caltech and Stanford, supported by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. Interestingly, another major beneficiary was Charles Lindbergh, whose 1927 tour of 82 cities in the US (after the Spirit of St. Louis had made its iconic non-stop flight from New York to Paris) was funded by the Guggenheims.

August 7, 1947. Among the streams of people heading in both directions across the soon-to-be-declared border are Satish’s parents Lakshmi and Devidayal. Much against their own wishes, they have left home and hearth in Lahore never to return, a scar that never really healed, especially with Lakshmi. Her recounting of that day, recalled years later to her grandchildren, was invariant–-in the scorching summer heat, she packed six white cotton sarees for herself and six white cotton shirts for Devidayal, took off her gold ring and locked it in her dresser drawer, thinking to herself that she would be back soon. The few days when Satish had no news of his family in Independent India shook him, but unlike so many families who lost everything, the Dhawan family, while displaced, was safe, and settled first in Simla and then in Delhi. With his judicial experience, Devidayal was asked to participate in the official reparations process after Partition, so his mind was occupied with attempting to heal some of those wounds, but for Lakshmi, the horrors they had heard of on both sides cut deep and could not be reconciled.

In late 1947, having used the year at UMN to obtain a Master’s in Aeronautical Engineering, Satish finally arrives in California. Today, on its website, the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT, where the G today refers to Graduate, not Guggenheim) has a simple statement: “The history of GALCIT (Graduate Aerospace Laboratories of the California Institute of Technology) is the origin-story of aerospace research. We welcome you to explore our department and how our current community is contributing to our legendary past.” If not explicitly stated at the time, it was already legendary in 1947.

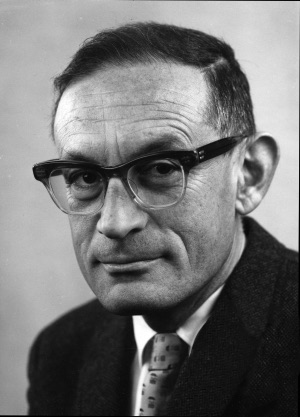

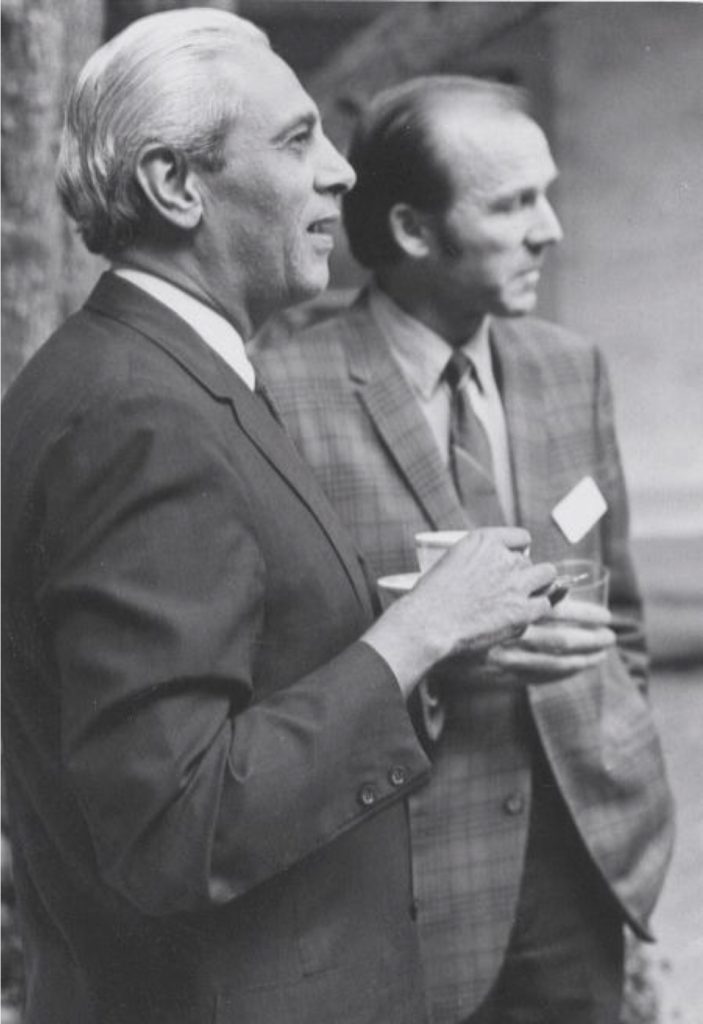

The story goes that when Satish arrived at GALCIT, he was keen to work with Hans Liepmann, whose reputation as a thinker, experimentalist, and a teacher par excellence was already well-established. However, Hans had a poor impression of a previous Indian student who had found working at the bench beneath his dignity, and was not inclined to meet this new student. Luckily for Satish, Hans overcame this prejudice upon being persuaded to meet the new arrival, and he was given the opportunity to work with the group. These friendships were foundational and his experience at Caltech changed Satish’s horizons. Hans, his PhD guide, and Anatol Roshko, a fellow student, were both drawn to post-war American research from elsewhere–-Hans from Germany in 1933 via Istanbul, and Anatol a few years later, from the Ukraine, after a childhood spent in a small mining town in Canada. The three immigrants formed a firm professional and personal friendship that lasted into the next generation–-we spoke with Anatol every New Year day until his death in 2017. When Hans passed away, the Caltech obituary had the following anecdote recalled by a student as a sophomore in a thermodynamics course taught by Liepmann: “Hans gave us a test and none of us did very well. And instead of coming back and being frustrated with us, Hans said, `I haven’t taught you well. Let’s try again.’’’ He was remembered for his wit and infectious enthusiasm. With Hans, Anatol and Satish shared a dislike of bombast and self-importance, and as Anatol recalls, “Hans was never politically correct and his agility with a polite insult often came in handy.” The experiences in Caltech left a strong impression on Satish and in many ways were defining for the self-reliant and hands-on engineer he became, and also reinforced his strong sense of democratic values. The informality of West Coast traditions also stayed with him, and although he often had to appear “suited and booted” later in his professional life, he always responded to people with a friendly directness.

While some in the field seem to draw a distinction based on a belief of the superiority of science over engineering, the over-arching philosophy at GALCIT, established by Millikan and Von Kármán, apparently saw no fundamental tension in the analytical tools and concepts of physical, mathematical and materials science as applied to understanding engineering principles with very real consequences. The stunning benefits of this thinking can be seen in its spin-off–-the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech. Where else might one see the investigation of deep space and planetary exploration of a mission like Voyager, starting with the nuts and bolts of building a sturdy little craft powered by a power source about as strong as the light in your fridge? Inspired by the realization that a once-in-a-lifetime event of planetary alignment was to occur in the late 1970s, Voyager was planned in 1965 to use the gravitational energy of that alignment to slingshot a spacecraft out of the solar system, into interstellar space. Picture if you will, in your mind’s eye, a friendly little metal box hurtling into the unknown with frail arms extended to the universe, capturing rare, fleeting particles, and telling us about the composition and energy of the vast heavens. That Voyager is still sending back data, 42 years after it was launched, surely tells us that the engineering and science could not be separated. All this was yet to come, but in 1947, Caltech already exemplified the philosophy of interdigitating borders between science and engineering, something that informed Satish’s experience there and influenced his own efforts later in life.

But in 1951, it is very unlikely that the Satish who headed back to India after his PhD would ever have imagined that his name would appear on the Caltech website in a short list titled “Legends of GALCIT”, or that a scholarship bearing his name would ensure a steady presence of bright young Indians at his alma mater.

1951–61: Bangalore Dream Days

Returning to India in 1951, Satish was fortunate to be selected for a position at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). “The Institute”, as it was called by all who worked there (as if there was really only one such place), was already a mature centre for research and education, well-connected with the world of science via its illustrious leaders, including C.V. Raman. Satish had wanted to join the IISc, knowing from his earlier stint in HAL about the establishment of the aeronautical engineering department headed by V. Ghatage, but was apparently asked to report to Allahabad University as his PhD training was in Mathematics as well as Aeronautics. As it turned out, his interview for the position of Scientific Officer was a strange experience–-he was made to sit at a desk while different interviewers came in one by one to assess his merits. One of them drew a graph on a sheet of paper and asked him what the axes should be labeled. Satish looked at it for a long time to decide how he should answer, and when the interviewer mistook that for ignorance and berated him, Satish was forced to inform that venerable gentleman that in fact the graph was upside down having been copied wrongly from a textbook held on the interviewer’s lap. Despite this sheer impertinence (and the blot of a second class in his Bachelor’s degree), he got the position. I have often wondered how different his life may have been if either of these issues were held against him. While showing up a supposed expert might be tolerated today, someone with a second division in any marks sheet would likely be excluded early in most institutional selection processes!

At the Institute’s Aeronautical Engineering department, in addition to his colleagues, Satish’s friendships were many and varied. Ramu (B. Ramaiah), a young man who had come to him as a domestic help was recognized for his skills and dexterity. Satish trained him in carpentry, working with him in the aero-workshop, lovingly crafting parts for his various experimental set-ups. Ramu’s son is now a successful engineer in Elon Musk’s SpaceX enterprise. J. Doss and Benedict Noronha were also Satish’s partners in the design and fabrication of devices required for his research. In those days, funds for research were virtually non-existent, and he was a firm believer in the notion of building what you needed, purpose-designed and purpose-crafted. Every year till he passed away in 2019, Doss would visit us at Christmas, bearing gifts and remembrances, his gentle affection enveloping us and connecting us to that golden time.

An intense discussion group at IISc grew out of meetings with D.D. Kosambi, a mathematician with a deep interest in Indian history and Marxist philosophy. In this group were A.R. Vasudeva Murthy (who was responsible for the development of indigenous silicon technology in the ‘70s), Amulya K.N. Reddy (a chemist who moved laterally to champion appropriate technology), M.A. Sethu Rao, who with Amulya, Satish and others, was involved in starting the Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology, to focus scientific efforts on problems of poverty. Vasudeva Murthy was not only an outstanding scientist, but also a philosopher with intimate knowledge of the scriptures and a socialist who lived his ideals; Satish’s respect and trust for him ran deep.

With his love of experimental innovation on a shoe-string budget, devising ingenious ways of addressing problems of aerodynamics that had implications for the growing aircraft industry, and his singular dedication to teaching, Satish’s energy was infectious. His impact on students and colleagues did not go unnoticed, and four years after joining IISc, he was asked to head the Aeronautical Engineering department.

1962: A Marked Man

In the ‘60s, Bangalore’s HAL airport had a single gate, which unlike today’s automated glass screens that swish onto an elevated aerobridge, was an actual metal gate with criss-cross bars on which you could sit and watch the Delhi flight come in, separated from the tarmac by a few feet. The landing strip at HAL airport was at a lower elevation than the gate, and once it had landed, only the tail of the aircraft was visible, shooting along disembodied till it turned and emerged in front of you.

Satish suddenly has to travel a lot more, when, at the age of 42, with his research work thriving, he is asked to be the next Director of IISc. He has serious reservations about leaving his lab–-my mother remembers him sitting in the same spot for three days, barely moving, his legs drawn up under his chin, thinking through this decision. He accepts the challenge, surely not knowing whether he will be overwhelmed by this role. My sense is that he prepared for this new role in the same way that he would plan for an experimental challenge–-thinking all around the problem and studying issues by reading and talking to people whose opinion he valued. Those opinions might have been quite different from his own.

In those years of the ‘60s at IISc, which seemed to us to last forever and define our own lives, Satish counted on Vasudeva Murthy, “Doc” B.S. Ramakrishna, his student-turned-colleague Roddam Narasimha, fellow aero-engineer “Rao” S.R. Valluri of NAL (National Aeronautical Laboratory, now known as National Aerospace Laboratories) and Raj Mahindra, HAL aircraft designer extraordinaire, for a deep friendship, and also as sounding boards for many projects and solutions to the inevitable moral tangles that administration entails. His bonds with Amulya Reddy and Sivaraj Ramaseshan were close, and the particular relationship that the three men shared was something indefinable. Amulya had started life as a chemist, but having built a career of academic excellence, including co-authoring a spectacularly successful textbook of electrochemistry, had found himself uncomfortable with the privilege and rarified nature of the pursuit of pure science–-he poured himself into building one of the first units dedicated to creating appropriate technology for application to real-world problems, particularly those faced by the rural poor.

1971: A Break, a Return and an Inflection

In the early years as IISc Director, Satish continued to lead the Aerospace Engineering department and kept up with his own research to ensure that his students could complete their degrees and move on. But around 1965, with many new research and academic programs being initiated at the institute, and an increased involvement with national programs (NAL, HAL, the IITs), he closed his lab. The decision cannot have been easy, considering how much he loved teaching and research, but it was practical, and permitted him to focus entirely on strengthening the institutional mechanisms that would enable others to achieve their potential, starting new departments and modernizing established ones. From those efforts grew the School of Automation, the Molecular Biophysics Unit, the Centre for Theoretical Studies and many others, each of which brought new people and energy to the Institute.

A much-needed break presented itself in 1971, when he permitted himself a sabbatical, having not taken a proper holiday in nearly 20 years. Hans and Anatol invited him to teach and participate in collaborative research for a year at GALCIT, and Caltech enabled this, having voted him a distinguished alumnus in 1969. Pasadena! Those magical names–-El Camino Real, Arroyo Seco, Mojave Desert–-we had heard stories featuring these mythic settings for years. Back in California, 20 years after his PhD, Satish reconnected with old friends, many still in the area and working in aerospace endeavours of various kinds.

In addition to working with Hans and Anatol in seeking engineering solutions to problems tiny and vast, Satish met often with William Pickering, Director of the JPL, where exciting advances were taking place. It was under Pickering’s leadership that JPL had been transferred from the US Army to the newly created NASA (but still under Caltech management). Pickering had led the Explorer satellite program which was given its brief in November 1957, just one month after the launch of Sputnik had started the space race. In an astonishing 83 days, JPL provided not just the satellite, but also the telecommunications and the upper stages of the rocket that was launched successfully on January 31, 1958. Pickering is quoted as saying “The event was symbolic of the mixing process between engineering and science, between the world and the research laboratory… it had mixed rocket technology with the universe, and reduced astronautics to practice at last.”

In the nearer reaches of the atmosphere, the amazing exploits of a former Caltech classmate, Paul MacCready, never ceased to fascinate Satish. MacCready had been a Navy pilot during the war, had won a world gliding championship, and after a Caltech PhD, had founded a company that pioneered the use of airplanes for studying meteorology. An ingenious inventor, he also designed the first human-powered aircraft, the Gossamer Condor, which was held aloft through the efforts of a pilot riding a bicycle in a gondola suspended below the wing. Years later when I was in grad school, Anatol took me to see “On the wing”, an early IMAX movie that chronicled the flight of a replica of the extinct pterodactyl Quetzalcoatlus northropii, designed and built to scale by MacCready, and robotically flown over Death Valley.

While Satish was on sabbatical in 1971, my mother Nalini, despite years away from the bench, also got a chance to do experiments again, which was a thrill for her. Trained as a cytogeneticist studying the chromosomes of an early ancestor of maize, she had introduced us to the mind-expanding world of microscopy back home in Bangalore: looking at magnified pond scum kept us riveted in the tumbling, swiveling antics of paramecia and euglena. That microscope was a loan from the IISc Microbiology department, after she decided to investigate what kinds of plant pollen were triggering Satish’s severe seasonal allergies. While at Caltech, working in the lab of Max Delbruck, the physicist-turned-biologist who had pioneered the development of molecular genetics, Nalini’s experiments involved splicing together the transparent thread-like hyphae of a fungus called Phycomyces. Max was investigating how this little fungus sensed light, hoping that these hybrid hyphae would allow him to understand the genetic basis for the origins of optical responsiveness. The project was completed by others in Max’s lab, but the experience gave Nalini a brief return to a world she missed.

The year of re-connection at Caltech gave Satish a breather from the hectic pace and distributed chaos of running an Institute, where firefighting becomes a full-time occupation. I have a memory of him walking down Lake Avenue in Altadena, balancing an ice-cream cone with three scoops of cherry vanilla. It was all too brief. In December 1971, Vikram Sarabhai passed away suddenly, and a new responsibility fell on Satish’s shoulders.

1972: “The larger the island of knowledge, the longer the shoreline of wonder’’2

Although life was busy in those early IISc years, Satish’s appointment to ISRO changed many things, since it catapulted him into a whirlwind of activity and expectations at a national level–-a time of experiment and uncertainty, hope and failures and successes, set on the back of India’s aspirations in space. His strong belief in the importance of a civilian space program stemmed from his early understanding of the peaceful uses of technology, his admiration for people such as P.M.S. Blackett, deeply felt all his life and honed at the Pugwash meetings. In building the launch center at Sriharikota, the displacement of the Yanadi tribe troubled him, set as it was against the massive displacements going on all over India in the name of development, and he worked hard to see that some reparations were made. Medha Patkar’s selfless struggle to keep the fate of displaced people in our collective consciousness aroused his greatest admiration.

Though entranced by the space program for its technical beauty, like Sarabhai, Satish never forgot the social possibilities and responsibilities of technology. One of his keenest interests was an early endeavour of ISRO for educational TV–-the SITE (Satellite Instructional Television Experiment) program where the first television programs were beamed to rural India. In the obituary Hans Leipmann wrote in 2002 that “Many years ago Satish told me that accurate weather prediction could improve India’s economy decisively. With the flock of satellites he helped organize, Satish did indeed do something about the weather.”

Although he became a thorough Bangalorean, Satish never learned the language–-but he loved the sound of particular Kannada words–-his favourite being garagasa (saw), enjoying the onomatopoeia and perhaps having to use that word in the carpentry workshop most often. After his death, when I was invited by ISRO to go through his office for any personal items, I came across a small saw, a small hammer and a few nails in a bottom drawer–-a talisman preserved in that high-tech office, surrounded by models of satellites and launchers, of his love for working with his hands. “50 years passed like a dream”, Vasudeva Murthy recalled, the day Satish passed away.

Four Friends in the ‘70s and ‘80s

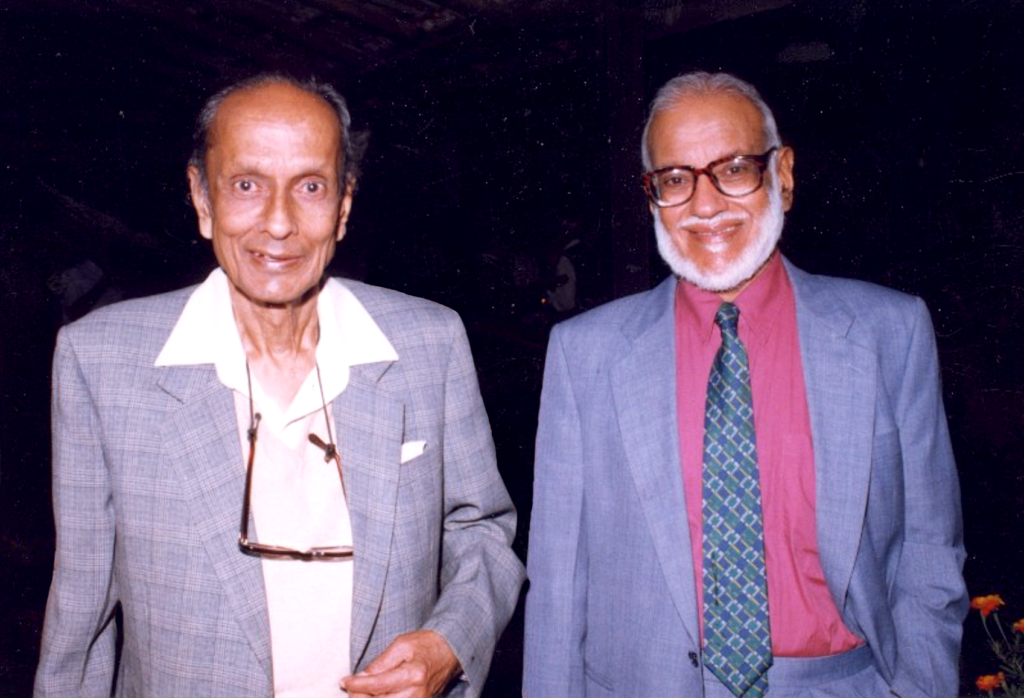

The friendship and values of another group Satish met with often also sustained him. Rad (V. Radhakrishnan), Sivaraj (Ramaseshan), and Goku (M.G.K. Menon), whose professional and personal paths crossed often, whose intellect, conscience, enthusiasm, wit and humour left a mark on each other, and whose individual and collective efforts made an indelible impact not only on scientific institutions, but on pretty much every individual whom they met.

I mourn this group of scholars and doers, not only for their individual natures, but because they had an uncommon commitment, deep integrity and lack of compromise. I have often wondered if that generation had a different collective consciousness, that informed a sense of purpose that was much larger than themselves. They came of age in an era of new nationhood and were held in thrall by the manner in which Gandhi and Nehru committed not only their reason and emotion but also their entire beings to the cause of freedom, and an idea of egalitarianism and self-determination. I began my recollection by feeling that whatever it was, it is rarely encountered today.

Remarkably, of these men who defined the scientific establishment of the ‘70s and ‘80s–-and this astonishes me–-three of them were “establishment’’ guys, while the fourth was clearly a maverick. But I would argue that where all four would be considered mavericks was in their fiercely independent minds; not influenced by prevailing winds, they were a class apart.

Goku, the nuclear physicist who was the go-to man for every crisis, was twice called upon to fill a sudden lacuna in scientific leadership, and because of his exemplary handling of these crises, was sought for his unflustered ability to apply his skill, vision, fairness and experience to an astonishing variety of new programs. Satish, the aeronautical engineer who was winkled out of his wind tunnel to lead IISc and ISRO. Sivaraj, the crystallographer who created new materials with applications as varied as heart valves and rocket parts, and then as a labour of love nurtured Indian scientific journals for decades. Rad, the iconoclastic astronomer and nautical enthusiast struck out on his own, ever the non-conformist, and by far the most outspoken of the four but finding a great deal in common with these other three. This diverse group of men spent a great deal of time together not just because of the committees and projects that demanded their collective talents and intellects, but because of a sense of shared purpose. What they had in common, apart from science and idealism and a strong sense of egalitarian values, was that they all came from privileged backgrounds but had the deepest distaste for bombast, never stood on ceremony, and never expected special treatment.

Having listened to them all from a very early age I will allow that they were all great pontificators and not easily interrupted, but all were deeply engaging, informed, thoughtful, amusing and charismatic holders-forth, persuasive and compelling, and utterly fascinating. What shone from all of them was the absence of overweening personal ambition in their affect. Don’t get me wrong, they were, each one of them, highly ambitious with the plans they wanted to put in place, no small measures for them. But from what I could tell, these ambitions were inclusive and disembodied from self.

It occurs to me that each of these men had been led by circumstances beyond their own making, stepping into a void knowing it was not what they would really like to do given a choice, but also realizing that when asked, they could not refuse to move laterally from their area of scientific interest to steering institutes.

To give an example of the collaboration and deep connection between these four men, I will quote from Rad’s talk at Goku’s 80th birthday [3]:

This style needed to be changed, and changed it was, thanks to help from Goku Menon and Satish Dhawan, another member of the RRI [Raman Research Institute] Trust, and the Chairman of the Governing Council of the Institute. An unprecedented relationship of mutual respect and rapport was established between the Institute and the newly created Department of Science and Technology, of which RRI was the first fundee, and which Prof. Menon steered as its Secretary for some years a little later. But from the word go, every last Rupee asked for by the Institute was granted by DST, and spent exactly as carefully budgeted, an unparalleled record for over two decades for a government-funded institute in this country, and perhaps elsewhere. Prof. Dhawan insisted on the Secy [Secretary] DST personally attending every Council meeting, and RRI was held up as a model to be emulated by the numerous other institutes that DST has not been able to stop accumulating ever since.

Rad’s words vividly describe the intertwined professional lives of these four men. What shimmers beneath this essentially professional account, is a subtext of the deep personal regard that they had for each other.

When I began to write this remembrance, my thought process was focused on how rare men like these four were, and I started by mentally decrying the degeneracy of my generation, and of our institutions that were set up with tremendous vision and aspiration, but where a generation later, in many places, regeneration seems elusive. It is easier to start than to sustain.

Like so many experimental scientists today, we are holed up in our labs, attempting to lead by example, cajoling our students to do experiments that address important questions, and trying to preserve a sense of wonder about the natural world while fighting to get around roadblocks, doing battle with institutional ossification and unresponsive systems, amid slogans from scientific agencies that exhort us to do useful things instead of creating more “useless” knowledge. These slogans strike home but we seem powerless to change. It felt ironic to me that science in India has never been better funded, more open, more collaborative or more outward looking, yet we seem to be in the grip of an existential crisis. Many of our young scientists seem intent on playing the game, acquiring awards and racking up the citations–-I doubt they would ever imagine that these icons of Indian science would never have dreamt of displaying their numerous awards mostly buried in bottom drawers in an interior almirah: I never once saw an award displayed in any of these homes.

But I realized very soon that my depressing summary is only one view of our world and by channeling the positivity of our four friends, I looked around me and found many great examples of people working beyond their constraints: scientists engaged in policy discussions and protesting against shortsighted or non-inclusive or unethical policies; young women scientists recognized with Bhatnagar and Infosys awards; mathematicians and physicists leaving the purity of equations and crystals and delving into messy biology; women at the helm of missile guidance programs; young scientists choosing to give up academic ivory towers for the rough and tumble of entrepreneurship and innovation or doing socially impactful work in making education egalitarian; IT professionals leaving lucrative careers to create mobile phone apps for gathering and disseminating medical information; scientists participating in educational sit-ins on university campuses; young journalists chronicling the world of woman scientists in India; student conferences on ecology and conservation attended by hundreds; computer scientists working to make self-learning accessible to illiterate and deprived city kids; engineering students contributing an experimental payload on an Indian satellite… Many of these were unimaginable a generation ago and would have delighted our four friends. I would argue that these examples are a living thread, deriving not as a consequence of their efforts, but springing from the same source that inspired our four. All around us are people with the imagination, heart and courage to put their considerable talents towards working for what they believe in.

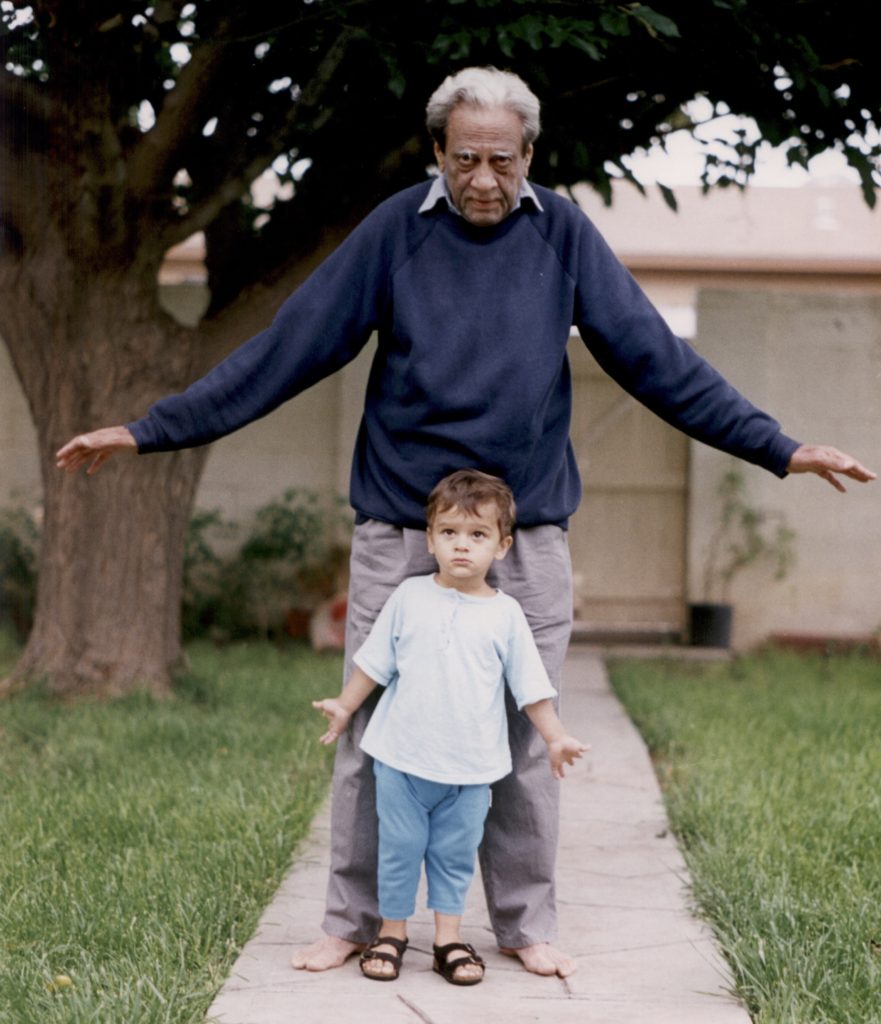

I also realized during my meditation on their lives that in looking from the outside, and with the benefit of hindsight, an observer can find early signs of greatness in individuals, but for the individuals themselves there is little clarity or time in the rush of life to contemplate what one might be remembered for. I am pretty sure that the young Rad who built and sailed a trimaran from Ipswich to Sydney, the epitome of adventure, would never have imagined that he would return to India to head the RRI and be remembered as a creator of a unique institutional model. I doubt that the young Sivaraj who waited at a college function in Wardha to get close enough to the Mahatma to physically touch him as a talisman, would ever have imagined that he would be remembered not only for being a distinguished physicist and materials scientist, and collaborator of Dorothy Hodgkin, but also for the enormous personal influence he had on championing the cause of rigorous scientific publishing in India. I doubt that the young Goku who planned the neutrino experiment in the KGF (Kolar Gold Fields) mineshafts ever imagined that he would be called upon to lead so many institutions of national importance, that he would do so with such extraordinary skill and would be remembered as the quintessence of sagacity and visionary leadership. I doubt that the young Satish who trained at HAL fixing British warplanes in pre-independence India would have imagined that one day we would have a vibrant indigenous civilian space program with a centre named after him.

At dawn

Two snowy egrets visit

Fly free with us, fly free

Of these four friends, Satish passed away in 2002, Sivaraj in 2003, Rad in 2011, and Goku in 2017. Let me quote Einstein on the death of his long-time collaborator and friend Michelangelo Besso, “Now Besso has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me. That means nothing. People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” So I believe that the time when the four friends made their special magic still exists in some parallel universe, but that in the here and now, the efforts of people like them, and the values they embodied surround us and give us hope that in each generation there will be those who will have the courage of their convictions and will prefer an engaged and passionate and examined life to just a comfortable one, will use their talents to contribute to a purpose larger than themselves, and will show independence in thought and action and work, and in doing so will create and lead and inspire.

References

[1] Maria Popova. 2015. “Ongoingness: Sarah Manguso on Time, Memory, Beginnings and Endings, and the True Measure of Aliveness”. Brain Pickings. Online at: https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/07/22/the-book-of-memory-gaps-cecilia-ruiz/.

[2] “A Report to the Government of India on Scientific Research in India’’ by Professor A.V. Hill (First published: August 1944). Edited by: Anasua Mukherjee Das and Anup Kumar Das. ICSI Working Paper Series, 01/2016.

[3] From V. Radhakrishnan’s public lecture on M.G.K. Menon’s 80th birthday, taken with permission from Vivek Radhakrishnan and the Raman Trust. katex is not defined