The inspiring life journey of the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, born on 12th May 1977 in the city of Tehran in Iran, was tragically cut short, barely at 40 on 14th July 2017, by that inconspicuous malady of cancer. As a remarkable achiever, she won some of the highest accolades of the mathematical community in her short life–-Gold Medals in the International Mathematical Olympiads two times, in 1994 and 1995, with a perfect score the second time, and the Fields Medal in 2014, being the crowning glory and the first-ever on several grounds.

The inspiring life journey of the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, born on 12th May 1977 in the city of Tehran in Iran, was tragically cut short, barely at 40 on 14th July 2017, by that inconspicuous malady of cancer. As a remarkable achiever, she won some of the highest accolades of the mathematical community in her short life–-Gold Medals in the International Mathematical Olympiads two times, in 1994 and 1995, with a perfect score the second time, and the Fields Medal in 2014, being the crowning glory and the first-ever on several grounds.

In the words of Cumrun Vafa, the Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Harvard University, “Maryam beautifully exemplified that the pursuit of knowledge is a timeless, borderless, and, yes, genderless adventure. Her untimely passing has deprived the world of math of a brilliant, yet humble talent at her peak.” Maryam Mirzakhani leaves behind a lasting legacy that the world pays tribute to, through the May12 initiative, supported by several organisations for women in mathematics, which also provided free screenings of the movie.

Nikita Agarwal

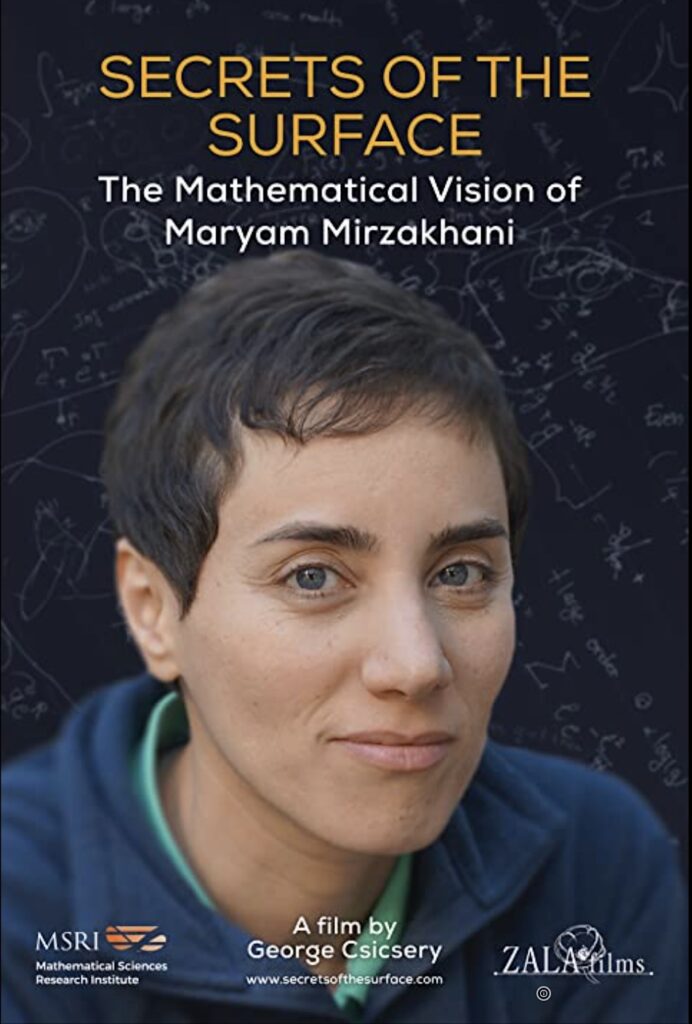

Released in January 2020, Secrets of the Surface: The Mathematical Vision of Maryam Mirzakhani is a documentary film about the mathematical genius, Maryam Mirzakhani (http://www.zalafilms.com/secrets/). The film is directed by George Paul Csicsery, a writer and an independent filmmaker. This masterpiece of a documentary is produced by Zala Films in collaboration with the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, and is filmed in Canada, Iran, and the United States. Since its release, the film has been widely screened across the world.

The narrative is enriched by seamlessly interweaving archival footage and images, with interviews and mathematical illustrations through animations, glimpses of life in Iran, and views of academic institutions both in Iran and in the United States. Besides, the changing background music along with the fascinating sceneries blend marvellously with Maryam’s life journey in different countries and cultures. The directorial nuances in the movie have brought out Maryam’s life journey, work, and personality in their full glory.

Iranian art and architecture serve as a natural inspiration for studying mathematics. The film displays this stunningly, using visuals at the very start of this artistic work. Interestingly enough, in her childhood, Maryam was not interested in mathematics. She wanted to be an author. However, her interest in and passion for mathematics was aroused as she grew up, leading to Maryam Mirzakhani becoming the first woman to win the Fields Medal since the inception of the award in 1936. This news was widely covered in the media all over the world and caught the attention of academics and the commoner alike. Maryam is an inspiration not just for this reason alone, but for several others. She started with several apparent disadvantages–-a female, an immigrant in the United States from Iran, among others–-but continued to produce top-quality mathematics even during the advanced stages of her struggles with cancer. The film highlights all these and much more. Each aspect of Maryam’s life is dealt with utmost care and has been portrayed with finesse. This hour-long film traces Maryam’s entire life journey without leaving the viewer feeling cramped.

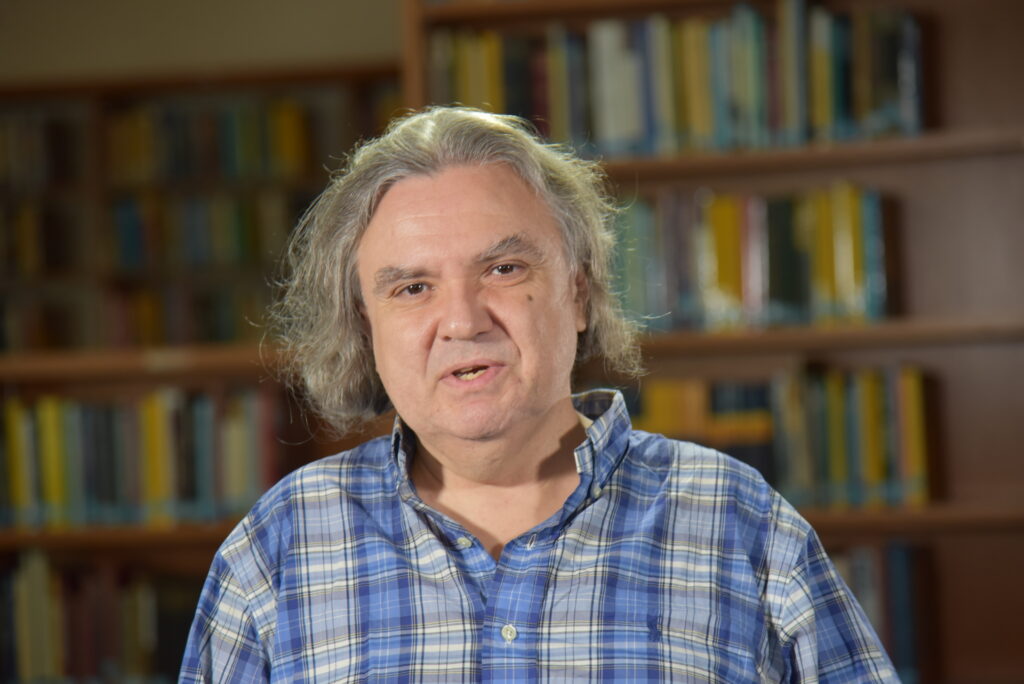

Striking a perfect balance between all the important landmarks of Maryam’s life, the documentary features insightful interviews with her family, friends, colleagues, students, and pioneers in the field. Omid Karamzadeh, Professor of Mathematics, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, recalls “Maryam, to me, was a child prodigy. She was not recognised as one though, even by her parents, and by her teachers. But she did excellent mathematics even when she was quite young… This is the first definition of being a child prodigy.” I personally believe that it is probably a good thing that she was not identified as a child prodigy, for it may have played a big role in letting her achieve her goals naturally, at her own pace, without being needlessly pressured by society to excel all the time in everything she did.

Even though Maryam had supportive surroundings that encouraged her to define and meet her goals, the film brings out the subtleties of the limitations and challenges of growing up as a woman in Iran. Her journey from Ms. Mirzakhani to Maryam for her male friends highlights the socio-cultural constructs in her own country, and the constraints they may have placed on a joyous natural expression of friendship. A large number of interviews with teachers and students from Iran about the general scenario in their country, specifically with respect to women in education, makes watching this documentary a compelling learning experience. A specific statement that at once captures one’s attention is by Hossein Masoumi Hamedani, Professor, Iranian Institute of Philosophy, “Women in Iran are not a privileged group. They have to try to find a better social situation by entering into art, or science. To belong to a disadvantaged group has this advantage that you are forced to work hard.”

Roya Beheshti Zavareh, an Associate Professor of Mathematics at Washington University, Maryam’s childhood friend, played an important role in her life journey. Their common friends said that the two were like sisters. They first met while in the eighth grade and remained inseparable all through Maryam’s life. Roya was truly a big support to Maryam, whether in convincing their teachers to allow them to participate in competitions across the world, breaking the so-called boys-only bastion by representing Iran in the IMO, or while transitioning from Iran to set up a life in the United States. The documentary does complete justice to their beautiful relationship.

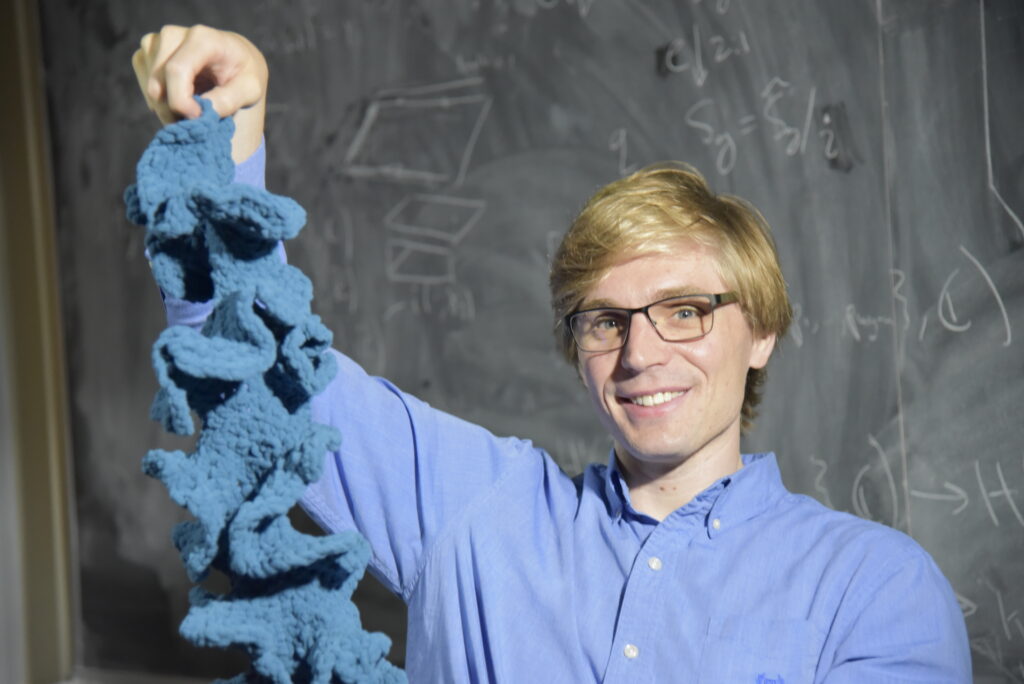

Mirzakhani’s work has left a long-lasting impact on mathematics. She focused on understanding the geometry and dynamics of hyperbolic surfaces. While Maryam has obtained several powerful results, her major breakthroughs have been the proof of Ratner’s theorem for moduli spaces (obtained jointly with two other mathematicians, Alex Eskin and Amir Mohammadi), and the Magic Wand theorem (with Alex Eskin). Her research contributions are not only useful and important in their own right, but have also helped solve several long-standing open problems. Her work has truly crossed mathematical boundaries. In the words of her doctoral advisor, Curtis McMullen, Maryam was largely guided by ‘ambitious and speculative’ mathematical insights, which made her an extraordinarily brilliant mathematician. The film shows how she would set her own goals, mostly aimed at solving difficult mathematical problems. To quote an excerpt from the interview of Alex Wright, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Michigan, “The crux of good mathematics is to find problems that are well-motivated and important, and somehow centrally connected to lots of other mathematics”. While working on problems, she had a great ability to see the entire big picture, or at least several aspects of it, at once. The moviemaker is simply ingenious in capturing the essence of Maryam’s deep mathematical works and conveying them through illustrations, simulations and elucidation from experts in the field, as well as a mathematics journalist, which makes it very accessible to the general public. It will surely generate excitement in the minds of youngsters especially those who are misled to believe that mathematics is dry and dull.

|

|

It is heartening to note that Iran had consciously set up centres of excellence to promote science and mathematics. It is crucial to have a research-oriented approach to teaching, which should catch the attention of policymakers across the world, and make them realise the importance of creating a flexible atmosphere that is amenable for realising individual potential, and fostering creativity.

Maryam was diagnosed with cancer before winning the Fields Medal and fought against this deadly disease till her last breath on July 14, 2017. In interviews with Maryam’s husband, Jan Vondrak, her friend Roya Beheshti, her teachers, collaborators and colleagues, the overpowering grief of their irreconcilable loss is clearly evident. The portrayal of this anguish in the documentary is restrained and devoid of theatrics.

Overall, it is a powerful documentary that captures Maryam’s life and work and brings out her personality in an extraordinary manner. The film is inspiring, deeply meaningful, poignant, and touches a chord at various levels. Its success lies in bringing to the forefront the goodness of Maryam as an individual, being a wonderful spouse, and parent to her daughter Anahita, and the special place she holds in people’s hearts, including those who were only professionally related to her. She is truly an inspiration and a role model, especially so for all women.

The moviemaker is ingenious in capturing the essence of Maryam’s deep mathematical works and making it accessible to the general public

It is remarkable how Csicsery has managed to incorporate possibly all the varied aspects of Maryam’s life and her personality, in an hour. This film is bound to have a deep impact on viewers from all walks of life, cutting across gender, ethnicity, cultures, and disciplines. I have watched it several times, and each time I gain a fresh perspective on Maryam’s life and the inspiration it provides. This documentary film will definitely be a classic and is worth possessing. It uplifts the spirit, motivates one to work despite limitations, fight against the odds that life presents, adopt the right attitude, and persevere to excel. All in all, this documentary is a must-watch, for all those seeking inspiration in the pursuit of their dreams and excellence.

Nikita Agarwal (nagarwal@iiserb.ac.in) is an Associate Professor of Mathematics at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhopal. Her main research interests lie in pure and applied dynamical systems.

Ramin Takloo-Bighash1

When Alice Silverberg and Sarah Greenwald asked me to review Secrets of the Surface: The Mathematical Vision of Maryam Mirzakhani, a movie I had seen once before and had enjoyed tremendously, I knew that the task of writing the review would not be just writing a review of a movie about some superstar–-Maryam was not just another famous mathematician, and the movie is not just the story of her mathematical ideas. The movie definitely tries, and does a very good job of, explaining Maryam’s mathematical ideas, but more importantly, it paints a portrait of Maryam, the person, and as someone who knew Maryam for a long time I felt that the film was very successful at this, rather intricate, task.

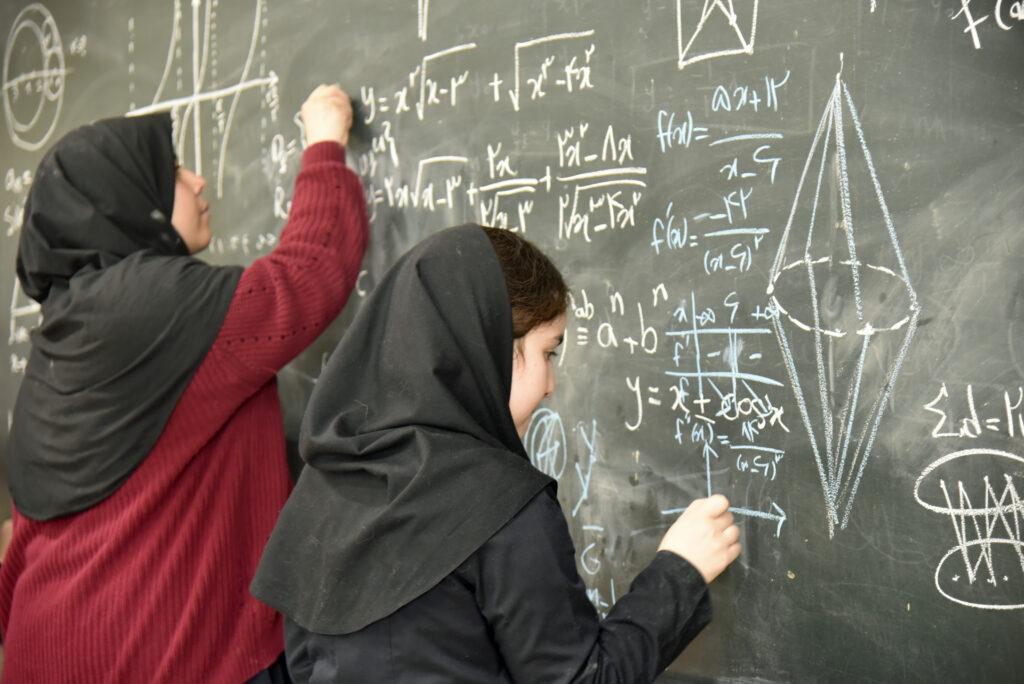

The film, before the credits, opens with a group of Iranian school girls from a high school for gifted students enthusiastically discussing a problem on the board, and I remember Maryam being one of these students back in 1992–-and the scene ends with one of the girls saying “There is a very good feeling behind solving the problems… and I feel Maryam Mirzakhani could show this passion to everyone.’’ And that’s the sort of thing Maryam would have said too.

The movie then starts in earnest showing photos from Maryam’s childhood in Tehran. The story then progresses through Maryam’s school years, her friendship with Roya Beheshti, her involvement with maths Olympiads, her paper joint with Professor Ebad Mahmoodian while still in high school, her undergraduate years at Sharif University, a tragic bus accident that severely injured her and took the lives of seven of her friends and classmates, her move to Harvard for graduate school, meeting Jan Vondrak, her first academic position at Princeton, meeting Alex Eskin at Princeton and her work on the Magic Wand theorem, moving to Stanford, fame, motherhood, Fields Medal, cancer, and her untimely death. The DVD contains several extra features which are worth watching:

- Space of all triangles up to similarity, by Grant Sanderson,

- Negative curvature,

- Pairs of pants,

- Pathological foliations,

- Maths in Iranian architecture,

- History of maths in Iran.

Maryam’s story is told by her husband Jan Vondrak, her friends (most notably Roya Beheshti, Kia Dalili, and Kasra Rafi), her professors back in Iran, her advisor at Harvard, Curtis McMullen, her students and mentees, and her collaborators. There are also several animation segments narrated by Erica Klarreich throughout the movie that very nicely explain Maryam’s contributions to mathematics. Fortunately, the movie is not all mathematics. By the end of the movie, through the intimate interviews with Maryam’s friends and colleagues, one gets a sense of what a genuinely good person Maryam was, that she was a good friend, that she was funny and goofy, that she was a good mother, that she was full of life, full of energy, that she was kind, the type of person about whom towards the end of the movie Anton Zorich says, “I wish there were more mathematicians, more people like this.’’

I met Maryam briefly in 1992 as a freshman in college through an introduction by Professor Ebad Mahmoodian. At the time Maryam was in 10th grade, but she and her friend Roya Beheshti already had a reputation of being very smart. Tehran is a large city, but somehow everyone knows everyone, and I kept hearing stories about this or that problem that Maryam and Roya had solved. Not surprisingly Maryam and Roya joined the maths Olympiad team in 11th grade and my friends and I, as former maths Olympiad team members, became their coaches. Much of what is shown in the movie, with rare exceptions, is the story of a generation of Iranian mathematicians: maths Olympiad, Sharif, coaching the maths Olympiad team, college maths competitions, grad school in the US or Canada, and finding jobs somewhere in the West. Maryam was the most successful of her generation, but she was not by any means an isolated case–-and this is something the movie does a very good job at capturing. The movie shows that there is an actual culture of mathematics in Iran, students are excited about mathematics and young people of all genders and all socioeconomic backgrounds study it. This culture did not exist half a century ago, and many of the people who are interviewed for the movie, people like Siavash Shahshahani, Yahya Tabesh, Omid Karamzadeh, Ebad Mahmoodian, Ali Rejali, and some others, who are not featured in the movie, are responsible for creating it.

In the movie, Hossein Masoumi Hamedani mentions in passing that Iranian women are not a privileged group, so they have had to work hard to overcome the systemic oppression imposed upon them. It is true that Maryam was perhaps subjected to less oppression because of the particular family she grew up in and the fact that her talent was discovered early on, but it might have been good if the movie had explored the lives of Iranian women further. For example, it might have been appropriate to mention that even though children with Iranian fathers automatically receive Iranian citizenship, until October of 2019 her daughter Anahita was not considered an Iranian citizen. (Finally, in October of 2019 a law was passed in Iran to allow Iranian mothers married to non-Iranians to pass on citizenship to their children–-it is believed that the law was enacted specifically to address Anahita’s case.) The Iranian society is far from utopia when it comes to equality of rights for women, and there are some places in the movie where this lack of equality is tacitly alluded to, e.g., Maryam wanting to play soccer with the boys, but I’m afraid that for the uninitiated these hints might be too subtle. Given that the DVD has an option for Persian captions, there is a chance that the director might have wanted the movie to be suitable for viewing in Iran and for it to pass through the Iranian regime’s censorship machine, and that might be the reason the movie stays away from political and social issues.

An important point highlighted in the movie is that while Maryam was growing up in Iran there was never any negative perception about women in mathematics

I very highly recommend this movie to anyone who has an interest, even tangential, in mathematics and science. Last semester we had a viewing of the movie at the University of Illinois Chicago which was very well-received. I think this movie should be shown to high school and college students everywhere for several reasons: First, it shatters the stereotypes of women’s weakness in maths. Second, it is the perfect antidote to the anti-immigrant and xenophobic sentiments spewed by the White House, not only because Maryam was an immigrant but also because many of the American scientists who are interviewed in the movie are immigrants (Roya Beheshti, Alex Eskin, Peter Sarnak, Cumrun Vafa, Jan Vondrak, etc.). Finally, it reminds people that it is wrong to equate a nation like Iran with its diverse populations and complex history and culture with its government, much the same way that it is wrong to equate a country like the US with its current administration. \blacksquare

Ramin Takloo-Bighash (rtakloo@math.uic.edu) is a Professor at the Department of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago. His research interests are in the areas of number theory, automorphic forms, arithmetic geometry and harmonic analysis on Lie groups. Like Maryam Mirzakhani, he is a graduate of the Sharif University of Technology in Tehran.

Footnotes

- This article originally appeared in the bimonthly AWM Newsletter of the Association for Women in Mathematics in its September–October 2020 edition, and is republished here, with permission of the author and the AWM Newsletter. ↩