A Brief Perspective of Events

About a century ago, the brilliant Bibhutibhushan Datta was awarded the higher doctoral degree (D.Sc.) by the Calcutta University in the field of applied mathematics. His teacher and guide was the famous Ganesh Prasad (1876–1935), who had built strong centres of mathematical research both at Banaras and Calcutta. Inspired by his guru, Datta also started studying ancient Indian mathematics and published about a dozen articles related to this subject between 1924 and 1927.

On 20 December 1927, Datta delivered an invited address on “Contribution of Ancient Hindus to Mathematics” at the Allahabad University Mathematical Association. It was published in the Association’s Bulletin during 1927–29. Later on, this long paper served as the nucleus of his major work (with A.N. Singh) entitled History of Hindu Mathematics: A Source Book. This book was published as Part I (Numerical Notation and Arithmetic) and Part II (Algebra) from Lahore (then in India) in 1935 and 1938, respectively. It may be pointed out that A.N. Singh (1901–1954) was another doctoral student of Ganesh Prasad, and the publisher of the book was the now famous Motilal Banarsidass who moved to Delhi after the 1947 Partition.

According to the authors’ preface in Part I of the History of Hindu Mathematics (HHM), they also planned to publish a third part of the book containing “the history of geometry, trigonometry, calculus and various other topics such as magic squares, theory of series and permutations and combinations”. But the planned Part III of the HHM never appeared during the lifetime of either Datta or Singh. In fact, Datta became a sanyasin1 in 1938 (with the new name Swami Vidyāraṇya) and died at Puṣkara (now Pushkar, in Rajasthan) in 1958. Singh, meanwhile, was busy with many activities (both academic and administrative) at Lucknow, Nainital, and Banaras, where he died in 1954. In this way, the writing of Part III remained seemingly incomplete. The manuscript waited with Kripa Shankar Shukla for his further action. The single-volume edition of Parts I and II (Bombay, 1962) does not say anything new about the expected Part III.

It is in this context that the successful completion of a doctoral thesis by T.A. Sarasvati Amma on “Geometry in Ancient and Medieval India” (Ranchi University, 1964) must be considered a significant event in the study of the history of Indian mathematics. However, another 15 years passed (due to various reasons) before her thesis was finally published in book form as Geometry in Ancient and Medieval India (Delhi, 1979). Like HHM Parts I and II, the presentation of Sarasvati’s research on ancient and medieval Indian geometry, is topic-wise. The coverage is quite thorough and comprehensive. A more detailed treatment of quadrilaterals, triangles and circles is not available elsewhere. In the meantime, a doctoral thesis on Indian trigonometry (by R.C. Gupta) was also completed under her able supervision (Ranchi University, 1971) but as yet remains unpublished.

After K.S. Shukla retired in 1979, his revision of HHM Part III started appearing slowly in the Indian Journal of History of Science (INSA, New Delhi). The section on geometry was published in Volume 15 (1980) and occupies a total of 68 pages on various topics. On the other hand, Sarasvati’s book has more than 270 pages on the subject. It is matchless and unique, and a standard work on the history of Indian geometry.

Birth and Family

Sarasvati Amma was born at Cherpulassery in the Palakkad district of Kerala. The year of her birth was 1094 of the Kollam (Kolamba) era which corresponds to 1918–19. She was the second daughter of her mother, Thekkath Amayathodu Kuttimalu Amma, and father, Marath Achutha Menon. Sarasvati had two brothers and two sisters. One brother served as an engineer at the Kerala State Electricity Board while the other had a short life. (The famous Kerala historian K.P. Padmanabha was their maternal uncle.)

Sarasvati’s elder sister, Padmalaya K. Nair, had a happy family life and often lived with her daughter in Chennai. Sarasvati’s younger sister, Rajalakshmi, was born in 1930 and completed her M.Sc. in Physics at the Banaras Hindu University. She later served as a lecturer in the same subject at the N.S.S. College, Ottapalam, Kerala. Rajalakshmi also showed her talent in literature. She wrote a few books and was given the Kerala Sahithya Academy Award in 1960 for her Malayalam novel Oru Vazhiyum Kure Nizhalukalum.2 Unfortunately, she committed suicide on 18 January 1965.

Sarasvati always signed her name as “T.A. Saraswathi” in the usual South Indian style. But the letter “h” was dropped in the North Indian style. The further change of “w” to “v” is according to the Indological tradition (as per international IAST notation system).

Sarasvati got divorced from her husband soon after their only son, Balagopala, was born. As a divorced woman, the social conditions and customs presented a mental challenge to her. But she picked up courage to emerge out of the situation and determinedly continued to pursue higher education and qualifications, so as to lead a dignified and self-dependent life. She was, however, reluctant to disclose dates of various events connected with her life.

Graduation and Research Work

Sarasvati obtained her first (basic) graduation degree from the University of Madras with a first class in Part II (Sanskrit) and Part III (Physics and Mathematics). She then went on to secure an M.A. degree in Sanskrit from the Banaras Hindu University in the first division with second rank. Later on, she also took another such degree in English literature from Bihar University with second class and second rank.

Sarasvati worked as a research scholar in the Department of Sanskrit at the Madras University for three years between 1957 and 1960. The research work was carried out under the supervision of the late V. Raghavan, one of the topmost Indologists of the 20th century.

In selecting the subject of Sarasvati’s research, Raghavan showed his analytical wisdom and soon “decided that she should specialise in the field of Indian contribution to mathematics, algebra and geometry” as “she was qualified in Mathematics” (see his Foreword in her 1979 book). In fact, Raghavan had been often, and rightly, pleading that “the history in India of the respective sciences should form a regular complementary part of the study of modern sciences in the Universities and should also be a legitimate subject for research degree for science graduates” (Ibid.).

“The history in India of the respective sciences should form a regular complementary part of the study of modern sciences in the Universities”

Since arithmetic and algebra were already covered in HHM (Parts I and II by Datta and Singh), Sarasvati’s research was rightly focused on ancient and medieval Indian geometry (Part III was not published at the time). She worked devotedly with great diligence, and her first research paper on “Śreḍhi-kṣetras” or “Diagrammatic Representations of Mathematical Series” appeared in the Journal of Oriental Research (Madras).3 The volume was published (with the usual delay) in 1961.

While working as a research scholar in Madras University, Sarasvati made full use of the rich libraries there. This applied not only to the printed books, journals, proceedings, etc, but also to handwritten manuscripts. Thus, she consulted and studied some important ancient and medieval Indian mathematical works that were unpublished. These include Parameśvara’s commentary on Līlāvatī,4 the most popular work on Hindu mathematics, and Bhāskara I’s Bhāṣya on the Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa I (born 476 ad).5 K.V. Sarma of the Sanskrit Department there made available to her a transcript of the manuscript of Kriyākramakarī,6 the best commentary on the Līlāvatī of Bhāskara II (12th century ad).

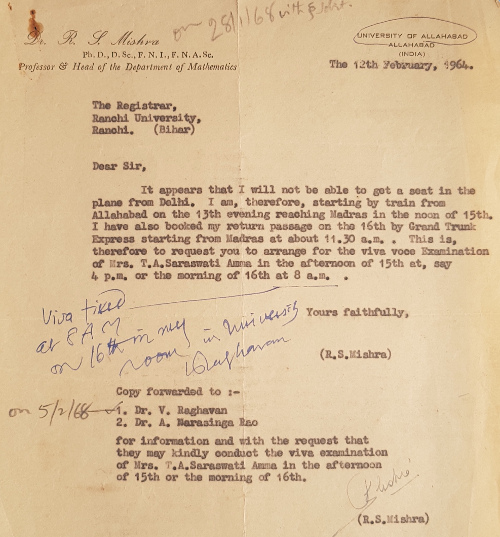

Although Sarasvati did her research work under Raghavan (Madras University), her thesis was submitted (in 1963) and processed by the Ranchi University (then in Bihar), and the final viva voce examination was held at Madras in 1964.

Professional Career and Research Activities

The cyclic quadrilateral is a figure of pride in Indian geometry, and has an eventful history. Brahmagupta’s formulas for its area and diagonals are considered to be among the most beautiful results of 7th century mathematics. Sarasvati’s paper “Cyclic Quadrilateral in Indian Mathematics”7 is quite comprehensive and shows her remarkable competence in dealing with Sanskrit and Malayalam mathematical texts.

In 1962, Sarasvati’s article on “Mahāvīra’s Treatment of Series”8 as well as her long paper related to Jaina mathematics9 (based on the Triloka-prajñapti) were published.

The Bulletin of the National Institute of Sciences of India [No. 21 (1963)] contains the papers presented at the National Symposium on the History of Sciences in India held at Calcutta in August 1962, held under the auspices of the NISI, now called the Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi. The Bulletin includes a significant paper by Sarasvati entitled “The Development of Mathematical Series in India after Bhāskara II” on pages 323–343. The importance of the paper lies in the fact that it falsifies a commonly held belief that no progress in mathematics was made in India after the 12th century ad. Also, it testifies that certain series (for \pi, sine and cosine) were already known in India about three centuries prior to their first appearance in Europe.

The cyclic quadrilateral is a figure of pride in Indian geometry, and has an eventful history. Brahmagupta’s formulas are among the most beautiful results of 7th century mathematics

With the successful completion of her Ph.D. degree (Ranchi University, 1964), Sarasvati became professionally well-known as a scholar in the field of early Indian mathematics. She continued to participate in conferences and write more articles. In March 1972, she presented her paper on “Sanskrit and Mathematics” at the first international Sanskrit conference (at New Delhi) organized by the Government of India. It may be pointed out that the proceedings of this conference were successfully conducted in Sanskrit by V. Raghavan.

Sarasvati also demonstrated her ability to guide doctoral research work in the field of ancient and medieval Indian mathematics. Under her supervision, I (then assistant professor of mathematics at BIT Mesra, also known as BIT Ranchi) completed my Ph.D. thesis on “Trigonometry in ancient and medieval India” (Ranchi University, 1970–71). This was based mostly on astronomical works in Sanskrit.

Sarasvati’s Struggle to Publish Her Thesis

Soon after the declaration of her Ph.D. result, Sarasvati initiated efforts to publish her doctoral thesis in the form of a book. Before preparing a press copy, she felt that it would be nice to elicit comments of an expert professional mathematician on the mathematical treatment contained in her thesis. For this, a copy of the thesis was given to K.M. Saksena, then head of the Department of Mathematics, Ranchi University. A research student of Saksena did the needful. This happened in July 1965. About a year later, when I contacted her for research work, she lent me the thesis to go through. Sarasvati was by then seriously keen to publish her thesis. However, due to delays, she had already forfeited the sanctioned 50 percent grant (by the Government of India) for the publication cost. It seems that some other efforts to obtain financial support also did not bring favourable results. So she made an attempt to publish the thesis privately, and the whole thesis was printed in a local press. But she found that a lot of printing errors still remained (having escaped proof-reading). So she had to abandon a whole lot of printed copies! I was able to get a full copy of this printed version from the G.E.L. Press, Ranchi in 1974 just for a look, and for the record.

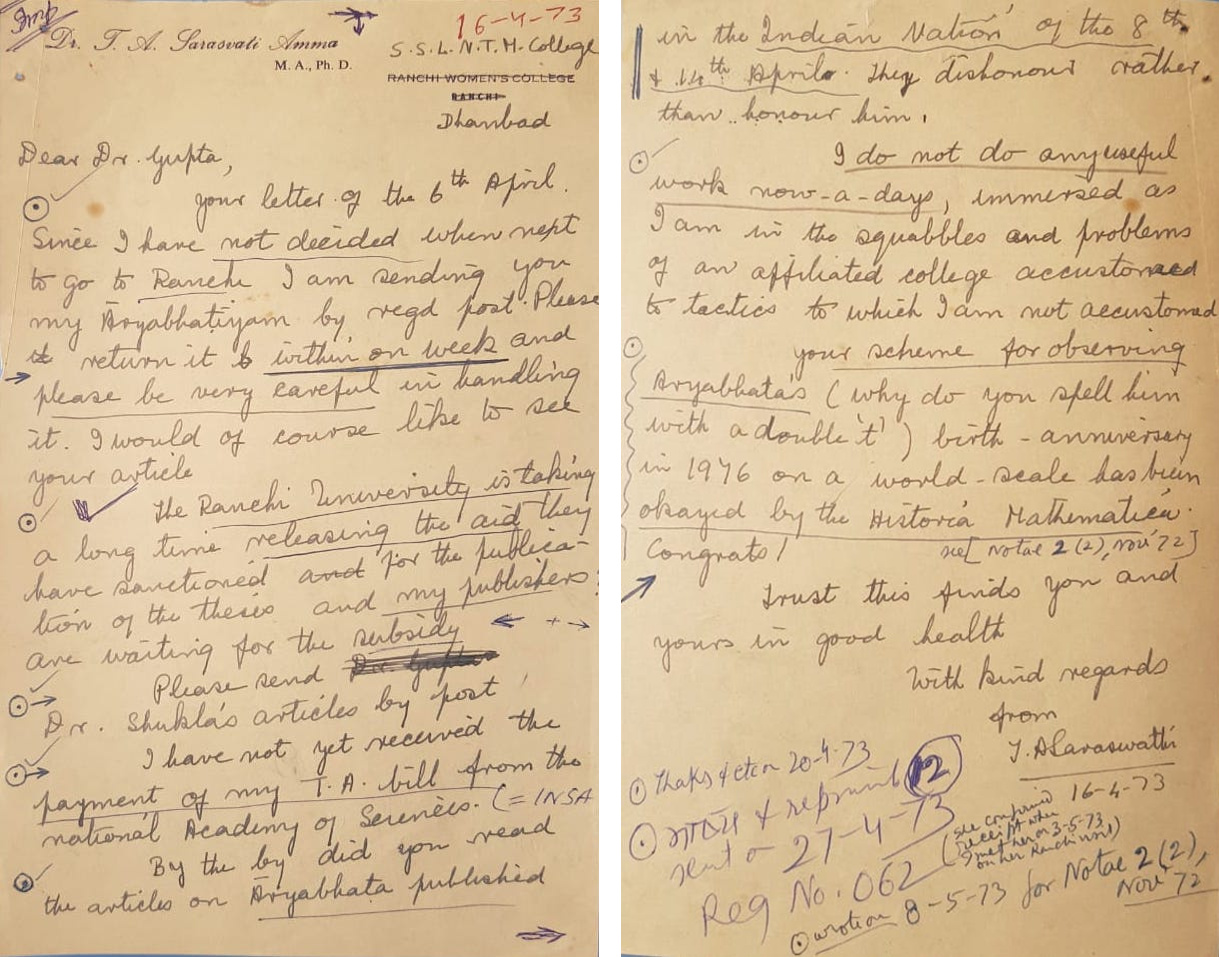

Fortunately, Ranchi University granted a subsidy cost to Motilal Banarsidass, who had agreed to publish the thesis. However, due to some further delay in releasing the subsidy, the book finally saw the light of the day only in January 197910 with a foreword by V. Raghavan dated 10 October 1972.

Evaluation of Sarasvati’s Book

Sarasvati’s book Geometry in Ancient and Medieval India was greatly welcomed by all in academic circles. She herself claimed it as the third in a series of books on Indian mathematics in pre-British India, the first two being the two parts (on Arithmetic and Algebra) of the famous History of Hindu Mathematics published more than 40 years earlier.

It may be noted that Datta and Singh’s (authors of the HHM) own part on Hindu geometry, published even after revision by K.S. Shukla (IJHS, 15: 121–188) in 1980, was not exhaustive enough to be regarded as a general history of Indian geometry, while Sarasvati’s claim is legitimately justified. Her book, according to Michio Yano, is not only quite exhaustive but “… has established a firm foundation for the study of Indian geometry and it will very surely provide stimulus to the students of history of mathematics.”11 Sarasvati has been highly praised for her achievements and for her enormous contributions to the field of history of Indian geometry. Her book is a significant milestone for a general history of Indian mathematics, especially for the geometric aspects. Almost all reviews have been found to be favourable. An early review states that the book is “an almost exhaustive survey” of geometry in Sanskrit and Prakrit literature right from the Vedic times down to the 17th century ad” (S. Balachandra Rao in Deccan Herald Magazine, Sunday, 21 October 1979). Another reviewer says that “an admirable feature of the book is the impartial scholarly attitude to the study and complete absence of parochialism” (D.G. Dhavale in the Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 1988. 69) as quoted on the covering jacket of the latest edition of the book (2017).

Sarasvati’s book is a significant milestone for the geometric aspects in the general history of Indian mathematics

Sarasvati’s book definitely helps in understanding the development of Indian geometry of the late Āryabhaṭa School (of south India) in which even algebraic results were geometrically demonstrated. The work challenges the theory that the Indian mathematical genius was predominantly computational, and that it eschewed proofs and rationales. The book is indeed outstanding and stands as a testimony to her scholastic prowess.

Her work on geometry was continued and supplemented later on through some research papers by myself, although my Ph.D. thesis on trigonometry is unpublished. Nevertheless, we now have the Bharatiya Trikonamiti Sastra by V.D. Heroor (Manipal, 2018) to serve the purpose. This book on Indian trigonometry is in English (258 pages).

Principalship, Retirement, and Last Days

T.A. Sarasvati Amma was the principal of the Shree Shree Lakshmi Narain Trust Mahila Mahavidyalaya (Women’s College), Dhanbad, from 1973 to about 1980. In those days, Dhanbad was in Bihar and the S.S.L.N.T. Women’s College was affiliated to Ranchi University. The new administrative assignment did not allow her any time for the research she liked to indulge in. In her letter of 16 April 1973 to R.C. Gupta, she expressed her disappointment in the following words: “I do not do any useful work nowadays, immersed as I am in the squabbles and problems of an affiliated college accustomed to tactics to which I am not accustomed.” Only a few can realize that for a truly devoted scholar, his or her research work is a real source of enjoyment and satisfaction.

After retirement from Dhanbad, she went back to Ernakulam in her native state of Kerala. In the meantime, I had been making efforts to promote the study of history of mathematics in India through the newly founded Gaṇita Bhāratī journal and as a member of the International Commission on the subject. In 1986, when I wrote to Sarasvati for her consent to review R.P. Kulkarni’s book Geometry According to Śulbasūtra for Gaṇita Bhāratī, she was surprised and agreed to review it. But at the same time, she also wrote (letter dated 11 January 1986):

When I retired from Principalship of Dhanbad College, I was hoping to get some time for research work. But I have been mistaken. With a big house to manage, my mother down with a fractured thigh bone, I have my hands full with household work…”.

Actually the big family house had already been sold and on 26 January 1986, the whole family moved out of Ernakulam to a smaller house in Ottapalam, Palakkad district. Her critical review of Kulkarni’s book was published in the same year (Gaṇita Bhāratī, Vol. 8). Shortly after this, her ailing mother expired

at the ripe age of about 90 years.

In the meantime, Sarasvati became a member of the Indian Society for History of Mathematics (Delhi) and started reading its journal, the Gaṇita Bhāratī and discovered that “many people were doing their Ph.D. research on Indian mathematics” (letter dated 18 March 1989). Of course, she was the first to get the degree in Bihar on the subject (Vol. 10, p.60 of Gaṇita Bhāratī). She had time to do more research now but the lack of a rich library at home was a hurdle in her old age.

Sarasvati must have been very happy to see the second (revised) edition of her book (Delhi, 1999) and must have felt much satisfaction that errors/misprints in the first (1979) edition were all corrected. Unfortunately, she had been suffering from bone cancer since long and after 27 August 1999, she was bedridden due to a broken bone in her left leg. She breathed her last on 15 August 2000. She came into this world with a purpose which she fulfilled. Her life and work will stand out as a memorable episode in the history of mathematics in India.

For a truly devoted scholar, his or her research work is a real source of enjoyment and satisfaction

In her honour, the Kerala Mathematical Association organizes, in its annual conference, a Prof. T.A. Sarasvati Amma Memorial Lecture. The first such lecture was delivered by P. Rajasekhara in March 2002. The third in the series was given by M.S. Sriram (University of Madras) on “Algorithms in Indian Mathematics” during the Annual Conference at Payyanur (January 2004). It is hoped that these lectures will appear in a consolidated book form in the future.

Footnotes

- One who has renounced worldly matters and dedicated oneself to spiritual quests.. ↩

- Now available in English, translated by R.K. Jayasree, as A Path and Many Shadows & Twelve Stories, Orient Blackswan. ISBN 9788125063513. ↩

- It appeared in Volume 28 (1958–59) on pages 295–310.. ↩

- Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, GOML no. R5160. ↩

- GOML no. 14850. ↩

- GOML no. R2754. ↩

- The paper was published in the Proceedings of the All-India Oriental Conference. 1961. 21: 295–310. The place-name (after author’s name) is given to be Ranchi, where Sarasvati was then recently appointed as a Lecturer in Sanskrit at the Ranchi Women’s College.. ↩

- The paper appeared in the opening volume of the Journal of the Ranchi University (pp. 39–50).. ↩

- Published in the Journal of the Ganganath Jha Research Institute (Allahabad), 18: 27–51.. ↩

- Published by Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, Pages xii+280, Rs. 60. ↩

- Historia Mathematica. 1983. 10: 470. ↩