An old newspaper excerpt from The Daily Chronicle (London), dated May 6, 1901, lends a canvas to reflect on the historical origins of social stereotypes of women, particularly Sofia Kovalevskaya, who shot to fame in male-dominated creative fields.

The excerpt below is taken from a newspaper article published in London in 1901. The names of three women cited are: Marie Bashkirtseff (1858–1884), who rose to fame as a painter after her training in the Académie Julian in Paris; Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855), the author best known for Jane Eyre, and Sofia Kovalevskaya (1850–1891), one of the most famous and celebrated mathematicians today. These are obviously extraordinary women—all three earned a place in the world of the arts or mathematics, areas which were regarded as male-dominated at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Most of their contemporaries were most likely to be stay-at-home wives and mothers, if not tending as servants or working in lower positions in factories or at farms to meet their financial needs or those of their families.

The objective of this article is to contextualize the remarks of this newspaper excerpt, and then to use it to show how famous women are vulnerable to be exploited within the framework of debates on the place of women in society.

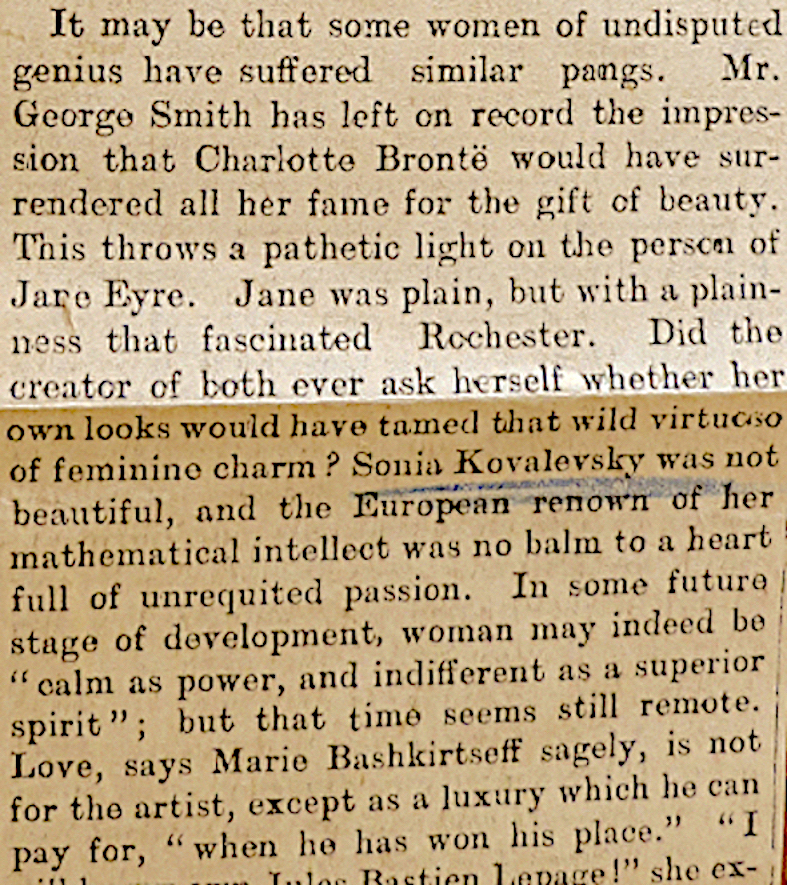

Here is a transcript of that article excerpt:

It may be that some women of undisputed genius have suffered similar pangs. Mr. George Smith has left on record the impression that Charlotte Brontë would have surrendered all her fame for the gift of beauty. This throws a pathetic light on the person of Jane Eyre. Jane was plain, but with a plainness that fascinated Rochester. Did the creator of both ever ask herself whether her own looks would have tamed that wild virtuoso of feminine charm? Sonia Kovalevsky [Sofya Kovalevskaya] was not beautiful, and the European renown of her mathematical intellect was no balm to a heart full of unrequited passion. In some future stage of development, woman [sic] may indeed be “calm as power, and indifferent as a superior spirit”; but that time seems still remote. Love, says Marie Bashkirtseff sagely, is not for the artist, except as a luxury which he can pay for, “when he has won his place.”

A contemporary reader will initially be able to easily answer the question posed in the title, namely what connects these three women. We are all familiar with this kind of publication, which can be called an “encyclopedic enumeration”. It lists, in alphabetical or chronological order, the names of women who excelled in the sciences or in the arts, along with some biographical information. Aimed at an increasingly younger audience, the narration of these extraordinary lives is often intended to encourage readers, especially girls, to pursue careers in science and technology disciplines.1

Such encyclopedic entries were also published regularly in the early 20th century, particularly in the press or dedicated works, as part of discussions on women and their role in society. The newspaper article featured here is one example. While the goals of feminist movements varied not only between countries, but also from group to group at the national level, demands for better education for girls and for access to higher education were, more or less, common. They also materialized in the second half of the century at the latest, especially in Europe [35][p. 319]. The publication of encyclopedic lists, in the form of articles or even of whole books,2 served to show—by citing historical and contemporary examples of women artists, doctors or scientists—that the supposedly “weaker” sex could succeed in exactly the same way in the same professions as men.

The newspaper extract is intended to warn young girls not to follow in the footsteps of Kovalevskaya, Bashkirtseff and Brontë, three women who were most often mentioned in these debates, whether as proofs of their intellectual prowess or, on the contrary, with diametrically opposed intentions. They are indeed united by much more than their professions, which were exceptional for the time. By the time the 1901 article appeared, all three had already died at relatively young ages. Brontë died in 1855 at the age of 38, probably due to complications from her pregnancy, Bashkirtseff succumbed to tuberculosis in 1884 at the age of 25, while Kovalevskaya died of a lung infection after her forty-first birthday in 1891. Several posthumous publications had already appeared on each of them, which, far from describing them as pioneering and accomplished women, presented them as supposed proof of the inevitable failure of women who considered a career other than that of wife and mother. This article examines these aspects of how the biographies of women were weaponized during the 19th century to confirm pre-existing assumptions about femininity. We will also see that this contention is still extant today when these women are staged like heroines.

A biography of Sofia Kovalevskaya

Within the framework of Images des Mathematics, let us focus more particularly on the case of the Russian mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaya, whose atypical career continues to fascinate even to this day. The youngest of three children in a family of lower gentry, she received private lessons in mathematics very early on, after her talent was recognized. Since women were not allowed to study in Russia at the time, she entered into a marriage of convenience with Vladimir Onufriyevich Kovalevsky (1842–1883) so that the latter could take her to study in German countries.

Kovalevskaya and her husband then returned to Russia, where their marriage of convenience turned into a real relationship. Their daughter Sofia, nicknamed Fufa, was born in 1878. Kovalevskaya then put her research on hold until 1879, when she made a presentation at the Sixth Congress of Naturalists and Physicians in St. Petersburg. There she met the young Scandinavian mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler (1846–1927) who had become one of Weierstrass’s most ardent admirers after a study trip to Berlin.

The supposed natural destiny of both genders

Even though Kovalevskaya’s life story tragically ended at the height of her career, it seems difficult for a modern reader to understand why the anonymous author of the newspaper clipping thought her biography could serve as a warning for young girls. To understand the flow of the author’s thought, the crucial clue is the use of the expression “women of undisputed genius” to describe the three women. It should be noted that Bashkirtseff, Brontë and Kovalevskaya are not qualified here as geniuses, but only described as possessing an “undeniable genius”, that is to say an above-average talent that does not define the person’s identity. This is not related to the discourse on genius and madness, also very widespread at the time,4 although the argument has some similarities. The gift of genius is understood by the author as being the cause of their pain and death. This association is here only implicit, but absolutely unequivocal for her contemporaries, who probably knew the life stories of these women. But how does the author arrive at this conclusion?

![Newspaper article “Sophie Kowalewski’’ by Anna-Charlotte Leffler (under the name A[nna] Ch[arlotte] E[dgre]n (Anna Charlotte Edgren), Illusterad Tidning, 32, 9 August 1884, pp. 269-270. Kovalevskaya had received a full professorship that year, although initially limited to 5 years, which made her the country's first female professor (“första kvinliag professor"](http://bhavana.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/article_sk2.jpg)

Such statements can be found, for example, in the work of the German physician Paul Möbius (1853–1907), grandson of the mathematician August Ferdinand Möbius (1790–1868), who is known today mainly for his fundamental work on migraine and Graves’ disease. Möbius published a book entitled On the disposition to mathematics (ber die Anlage zur Mathematik), conceived as an attempt to locate a certain area of the human brain as a causal factor of mathematical talent. There he explained in detail why he viewed women as inferior, weaker,5 than men, both physically and intellectually.

For this reason, Möbius was convinced that the few women who excelled in the field of mathematics, which for him and many contemporaries was inherently the most masculine of disciplines, were only exceptions (in the negative sense of the term). Implicitly referring to the theories of degeneration which had also become popular at the time, notably thanks to Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), he declares that Kovalevskaya or Sophie Germain, among others, are pathological phenomena, classifying them as “Products of degeneration”. Möbius also devalues their achievements. Even if they had possessed much more mathematical talent than the average woman, it is generally certain, he asserts, that “the sciences in the strict sense have not known and cannot expect any enrichment from women”. Firmly anchored in the theory according to which women do not have original faculties but only reproductive ones, he concedes to them only that they are “predisposed to be ‘model pupils'”, since their memory and their capacity for comprehension are “not at all bad”. At best, he said, a woman could use “the method taught by the teacher, in a similar spirit.” For him, this also applies to the mathematical publications of Kovalevskaya, which according to Möbius are only “elaborations of the thoughts conceived by Weierstrass” [32][p. 84 and 86].

Möbius was delighted to find that independently of him, the Italian mathematician Gino Loria (1862-1954) had come to similar conclusions [32][p. 93]. In two publications, Loria also asserted that women mathematicians, on the one hand, were the exception and, on the other hand, had depended on the influence of a strong man—“her own [intellectual] father”—who tended to be one of the most eminent mathematicians of the time. Although the epistolary relationship between Karl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) and Sophie Germain was obviously very different from that of Weierstrass and Kovalevskaya, the two here are considered to be equivalent. As with Möbius, the mathematical results obtained are presented by Loria as being due to the intellectual paternity of the man and the simple execution of the woman [27][p. 391], [28].

The activity in a profession understood as masculine, perceived here as being against nature, is according to these two authors the reason why Kovalevskaya naturally had to suffer. For Möbius, she is even the best proof that “male talents” are absolutely not a gift for women, but a “stake in the flesh”, because they destroy “female happiness in life” [32][p. 92]. For this hypothesis, which from a current point of view is quite debatable, he can also refer to a source which at first glance seems to be authoritative.

Love fulfilled as the real goal in a woman’s life

This source is the biography of Kovalevskaya by Anna Charlotte Leffler (1849–1892), sister of Gösta Mittag-Leffler and a close friend of the mathematician, but also an internationally renowned author. As the book’s subtitle — What I Learned With Her and What She Told Me About Herself — already indicates, her 1892 account is based on shared experiences, stories told by Kovalevskaya as well as extracts from directly quoted correspondence.

Of course, this does not mean that this is an objective account. Leffler herself described her biography as a “poem”. It is not difficult to see that, using on the one hand purposely chosen anecdotes and quotes, but also her personal assessment often expressed openly, she did not wish to write the portrait of a woman who triumphed in a male domain. Based on her own experience, Leffler explains that fulfilled love is a woman’s supreme goal in life and diagnoses that this is precisely what Kovalevskaya never achieved, although it was her greatest desire. Therefore, she presents her friend’s life as that of a failed woman, torn between her heart’s desire and her profession, and who for this reason ended up perishing.

It is irrelevant for the purposes of this article to discuss whether Leffler’s claims are truer than Marholm’s, or whether both give an equally distorted picture. What is significant here is that as a result of these two biographies, it seemed clear to the vast majority of contemporaries that Kovalevskaya’s life was ultimately to be seen as a failure, as she had eluded her true destiny as a woman and that she had paid a high price for it.

For a modern reader, to understand how their contemporaries arrived at this same judgment concerning Brontë and Bashkirtseff is even more difficult than in the case of Kovalevskaya. Indeed, Bashkirtseff was only twenty five years old at the time of her death, while Brontë was not only happy in marriage but also pregnant. Once again, this is explained by publications that paint a romanticized portrait of the two women. These portraits are not necessarily based on facts, but rather on individual interpretations of authors who have adapted their biographies according to the opinions they already had about the fate of women. In Brontë’s case, the writer Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865) sought to refute the all too frequent accusation of “rudeness” (coarseness7) of the Brontë sisters by deliberately portraying the author as a sober, nun-like woman who did not seek to thrive in the natural and feminine duties and tasks of wife and housewife [31][chapter 3].

For Bashkirtseff, the portrait has its origin in the diary she wrote (105 volumes), of which excerpts were published in several volumes at the beginning of 20th century and was an international commercial success [15][p. 46-49]. Bashkirtseff presents her life, with a view to future publication, as an authentic portrayal of an artist’s bitter struggle for self-actualization [29][p. 96]. Due to this self conjured image, she is presented by Marholm as another negative example, of a woman who does not devote her life to a man must end up “withering away” and dying from the resulting loneliness [30][p. 4]. At the turn of the 20th century, we find more mentions of Kovalevskaya and Bashkirtseff side-by-side in various publications to confirm the same hypothesis, such as in an article by writer Isabel F. Hapgood (1851–1928 ): “Deep in their hearts, women who have become famous and have, for one reason or another, missed the domestic career expected of women, still regret this loss” [12][p. 537].

Smart women are always ugly

The thesis according to which the women who, because they had not succeeded in winning a man’s heart, had failed in their lives despite great professional success, wound up being explained with the assertion that they had not been attractive enough to do so. In this regard, it is therefore not surprising that, in the newspaper clipping analyzed here, Kovalevskaya and Brontë are described as not being attractive enough, an idea also affirmed in the numerous biographical writings concerning them at that time.8

Laura Marholm is the one who put the most emphasis on Kovalevskaya’s appearance. For example, following the widespread need for classification at the time, it divides Russian women into two categories. According to her, there are, on the one hand, sensual and feminine women, who also have abundant erotic qualities. The other group, in which she counts Kovalevskaya, is quite the opposite. She paints a picture of the women who possess the masculine attributes usually mobilized in the theory of gender characters: they are clear, courageous, strong and “reasoning”. But this is also reflected in their appearance, which is not very feminine:

Kovalevskaya’s appearance would subsequently have had a negative effect on her efforts to find a husband, in particular because she would have started this search too late, when she was already “a dry old little female” [30][p. 163]. It is quite possible that this statement comes from the famous pedagogue Ellen Key (1849–1926), with whom Marholm had come into contact for the purposes of her essay on the mathematician and who, unlike her, had been friends with Kovalevskaya. In her biographical description, Key indeed also indicated that as a smart woman it was difficult to find a husband anyway. And if, according to Key, one belonged like Kovalevskaya to these women “in whose cradle the graces did not deposit their gifts, then the fate of such a woman will be tragic” [22][p. 56].

The unflattering judgment on Brontë’s appearance by her editor, George Smith (1824–1901) is mentioned in the newspaper article, who notices that the shape of her mouth disfigures her face and that her head is too big. He also claims that she was mostly aware of being less beautiful than average, and would willingly have traded her fame and talent for greater beauty [34][p. 90]. Interestingly, a similar claim about Kovalevskaya is also found in Ellen Key’s book. She notes that the mathematician would have often said that she would gladly give her genius for beauty, but doubts that to be true. In reality, she would have wanted everything, including beauty and genius [22][p. 69].

What may appear today as a particularly ambitious wish must quite simply have been an oxymoron in the eyes of her contemporaries. Indeed, describing Brontë and Kovalevskaya as ugly did not only offer one reason why they had not found a husband. For their contemporaries, this was inseparable from their above-average intellect, their genius, and their need to combine it with a career then so atypical for women. It was indeed accepted, at least since the 18th century, that women could be either beautiful or educated,9 in particular because it was believed that only the women who were not beautiful enough to find a husband who provides for their needs were educated [24][p. 35].

Modern reception

In the wake of Marholm, for a long time no publication appeared in which the appearance of Kovalevskaya was presented in a positive way. However, while Brontë’s supposed ugliness — despite the fact that there is virtually no verified portrait of her — has been discussed repeatedly in recent literature [9][p. 55-59], a complete turnaround in the appreciation of the mathematician took place from the 1930s. It probably originated in an obituary written in 1935 by Hermann Weyl (1885–1955) on his colleague Emmy Noether (1882–1935). Weyl elevates Kovalevskaya to the rank of embodiment of femininity, both in her outward appearance and in connection with the gender character attributes, which still prevailed. He notes that she possessed not only a “feminine charm” but also a “most complete personality”, the “personality of a woman” including the emotional side that Noether lacked: “With [Kovalevskaya], you see the tension between her creative mind, her life and her passion, and the spirit of self-mockery that ironically looks at her own desperate conflict. How far from the possibilities of Emmy!” She is therefore an antithesis of Noether, whom he characterizes as masculine. Noether is well presented as the better mathematician, but Weyl says about her exactly what Key said about Kovalevskaya some thirty years earlier: “No one could say that the Graces stood near her cradle” [48][p. 219].

It is certainly no coincidence that Eric Temple Bell (1883-1960) describes Kovalevskaya as “pretty” and speaks of a “dazzling young woman” in his wholly inappropriately-titled Men of Mathematics published two years later [3][p. 424]. Yet even today, Kovalevskaya is described not only as beautiful, but even as “certainly the most beautiful mathematician of both genders” [7][p. 78].

In modern representations, Kovalevskaya is thus more than a model. She is often put on a pedestal, not necessarily in a conscious manner, and presented as a symbolic figure who must refute any prejudices about women scientists. It is therefore supposed to serve not only as proof that women are capable of the highest achievements in mathematics, but also that they do not necessarily have to be ugly to be interested in research.

Kovalevskaya, as also Bashkirtseff and Brontë, are revered today as pioneers and heroines, women who, thanks to their exceptional achievements, were able to succeed themselves in the then almost exclusively male fields of mathematics, painting or literature. No one would think of attributing their early death to anything other than substandard medical care, or considering their career choices to have been the source of a life of frustrated lust.

Bashkirtseff, Brontë and Kovalevskaya have thus become canvases on which various authors project their respective theses on the place of women in the sciences and the arts, as they could have been at the beginning of the 20th century. While it should of course not be forgotten that today there are undoubtedly more varied portraits on these three extraordinary women, others pursue a clear agenda, which is particularly the case for the modern encyclopedic enumerations mentioned above. The intention behind this form of projection, namely to present more precise biographies of extraordinary women as role models for girls, is undoubtedly laudable from a modern perspective. But certain elements indicate that this act could have the exact opposite effect:

Myths and rhetoric undermine science and, in my opinion, help alienate young people (and girls in particular) from it: they produce the more or less conscious conviction that women or girls must be exceptionally good and heroic in order to devote themselves to science or mathematics. (see [10][p. 309])

This does not mean that young women should be deprived of such biographies from now on. However, it is necessary to combine this approach with a discussion of the new prejudices that have arisen, while presenting more realistic models, in order to show young women what are the real prerequisites and the various career possibilities in mathematics, and thus get enthusiastic about this discipline.

References

- Anderson, Becca (2020). Book of Awesome Women Writers: Medieval Mystics, Pioneering Poets, Fierce Feminists and First Ladies of Literature, Mango Media Inc.

- Audin, Michèle (2011). Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya, Paris: Springer.

- Bell, Eric Temple (1937). Men of Mathematics. The Lives and Achievements of the Great Mathematicians from Zeno to Poincaré, New York: Simon und Schuster.

- Boccaccio, Ioannis (o.D.). De mulieribus claris ad Andream de Acciarolis de Florentia, Alteville comitissam, liber incipit congratulate.

- Cooke, Roger (1984). The Mathematics of Sonya Kovalevskaya, New York: Springer Verlag.

- Daston, Lorraine (1997). “Die Quantifizierung der weiblichen Intelligenz”, in Renate Tobies (ed.), “Aller Männerkultur zum Trotz”. Frauen in Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften, Frankfurt u.a.: Campus Verlag, p. 69–82.

- Derman, Emanuel (2004). My life as a Quant. Reflections on Physics and Finance, Hoboken: Wiley.

- Dohm, Hedwig (1902). Die Antifeministen, Berlin: Ferd. Dümmlers.

- Franklin, Sophie (2016). Charlotte Brontë Revisited. A View from the Twenty-First Century, Glasgow: Saraband.

- Govoni, Paola (2020), “Hearsay, Not-So-Big Data and Choice: Understanding Science and Maths Through the Lives of Men Who Supported Women”, in Eva Kaufholz-Soldat and Nicola Oswald (eds), Against All Odds. Women in Mathematics (Europe, 19th and 20th Centuries) , Springer Verlag.

- Halligan, Katherine & Sarah Walsh (2018). HerStory: 50 Women and Girls Who Shook the World, Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers.

- Hapgood, Isabel F. (1895). “Notable Women: Sony Kovalevsky”, The Century, vol. 5, no. 4, p. 536–539.

- Harless, Johann Christian Friedrich (1830). Die Verdienste der Frauen um Naturwissenschaft, Gesundheits und Heilkunde, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Hausen, Karin (1976). “Die Polarisierung der“ Geschlechtscharaktere”. Eine Spiegelung der Dissoziation von Erwerbs- und Familienleben.”, In Werner Conze (ed.), Sozialgeschichte der Familie in der Neuzeit Europas. Neue Forschungen, Stuttgart: Klett, p. 363–393.

- Herrmann, Anja (2009). “Notre-Dame der Schlafwagen oder die Maskeraden der Marie Bashkirtseff”, in Renate Berger & Anja Herrmann, Paris, Paris! Paula Modersohn-Becker und die Künstlerinnen um 1900, Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, p. 39–58.

- Hibner Koblitz, Ann (1993). A Convergence of Lives: Sofia Kovalevskaia, Scientist, Writer, Revolutionary, 2nd edition, Boston: Birkhäuser.

- Ignotofsky, Rachel (2016). Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World, Ten Speed Press.

- Ignotofsky, Rachel (2019). Women in Art: 50 Fearless Creatives Who Inspired the World, Ten Speed Press.

- Jackson, Libby (2018). Galaxy Girls: 50 Amazing Stories of Women in Space, Harper Design.

- Kaufholz-Soldat, Eva (2017). “'[..] the First Handsome Mathematical Lady I’ve Ever Seen!’ On the Role of Beauty in Portrayals of Sofia Kovalevskaya”, BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the British Society for the History of Mathematics, vol. 32, no. 3, p. 198–213.

- Kaufholz-Soldat, Eva (2019). A Divergence of Lives. Zur Rezeptionsgeschichte Sofja Kowalewskajas um die Wende vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert, Doctoral thesis, Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz.

- Key, Ellen (1908). Drei Frauenschicksale, Berlin: Fischer Verlag.

- Klein, Felix & Sommerfeld, Arnold (1897). Über die Theorie des Kreisels, Leipzig: Teubner.

- Kuhn, Bärbel (2000). Familienstand ledig: ehelose Frauen und Männer im Bürgertum (1850-1914), Köln: Böhlau-Verlag.

- Leffler, Anna Charlotte (1892). Sonja Kovalevsky. Hvad jag upplefvat tillsammans med henne och hvad hon berättat om sig själf, Albert Bonniers Förlag.

- Linde, E. (1908). “Sonja Kovalevsky. Ein Bild ohne Worte”, Allgemeine deutsche Lehrerzeitung, vol. 60, no. 18, p. 199–202.

- Loria, Gino (1903). “Women mathematicians”, Scientific Review, vol. 20, p. 385–392.

- Loria, Gino (1904). “Women mathematicians again”, Scientific Review, vol. 21, p. 338–340.

- Mader, Rachel (2009). Beruf Künstlerin. Strategien, Kontruktionen und Kategorien am Beispiel Paris 1870-1900, Berlin: Frank & Timme.

- Marholm, Laura (1895). Das Buch der Frauen. Zeitpsychologische Porträts, Paris u.a.: Albert Langen.

- Miller, Lucasta (2013). The Brontë Myth, London u.a.: Random House.

- Möbius, Paul (1900). Über die Anlage zur Mathematik, 2nd ed. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Murphy, Sharon (1998). “Charlotte Brontë and the Appearance of Jane Eyre”, Brontë Society Transactions, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 17–26.

- Orel, Harold (1997). The Brontës: Interviews and Recollections, University of Iowa Press.

- Palatschek, Sylvia & Bianka Pietrow-Enker (2004). “Women’s Emancipation Movements in Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century: Conclusions”, in Palatschek, Sylvia & Bianka Pietrow-Enker (eds.), Women’s Emancipation Movements in the Nineteenth Century: A European Perspective, Stanford: Stanford University Press, p. 301–336.

- Rasche, Ulrich (2007). “Geschichte der Promotion in absentia, in Rainer Christoph Schwinges (ed.), Examen, Titel, Promotionen. Akademisches und staatliches Qualifikationswesen vom 13. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert, Basel: Schwabe Verlag, p. 275-351.

- Rebière, Alphonse (1889), Mathematics and mathematicians. Thoughts and curiosities, Paris: Librairie Nony & Cie.

- Rebière, Alphonse (1894). Women in science. Conference given at the Cercle Saint-Simon on February 24, 1894, Paris: Librairie Nony & Cie.

- Rebière, Alphonse (1897). Women in science, 2nd, Paris: Librairie Nony & Cie.

- Rowold, Katharina (2010). The Educated Woman: Minds, Bodies, and Women’s Higher Education in Britain, Germany, and Spain, 1865-1914, London: Routledge.

- Schiebinger, Londa (1991). The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Schmidt, Jochen (1985a). Die Geschichte des Genie-Gedankens in der deutschen Literatur, Philosophie und Politik 1750-1945. Band 1: Von der Aufklärung bis zum Idealismus, Göttingen: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Schmidt, Jochen (1985b). Die Geschichte des Genie-Gedankens in der deutschen Literatur, Philosophie und Politik 1750-1945. Band 2: Von der Romantik bis zum Ende des Dritten Reichs, Göttingen: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Segler-Messner, Silke (1998). Zwischen Empfindsamkeit und Rationalität. Der Dialog der Geschlechter in der Italienischen Aufklärung, Berlin: Erich Schmidt.

- Tollmien, Cordula (1995). Fürstin der Wissenschaft: die Lebensgeschichte der Sofja Kowalewskaja, Weinheim: Beltz & Gelberg.

- Tollmien, Cordula (1997). “Zwei erste Promotionen: Die Mathematikerin Sofja Kowalewskaja und die Chemikerin Julia Lermontowa”, in Renate Tobies (ed.), “Aller Männerkultur zum Trotz”. Frauen in Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften, Frankfurt ua: Campus Verlag, p. 83-130.

- Tsjeng, Zing (2018). Forgotten Women: The Scientists, Hachette UK.

- Weyl, Hermann (1935). “Emmy Noether”, Scripta Mathematica, vol. 3, p. 201–220.

Footnotes

- Here are some recent publications whose titles already bear witness to this state of affairs: Ignotofsky, Rachel (2016), Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World; Jackson, Libby (2018), Galaxy Girls: 50 Amazing Stories of Women in Space; Tsjeng, Zing (2018), Forgotten Women: The Scientists; Anderson, Becca (2020), Book of Awesome Women Writers: Medieval Mystics, Pioneering Poets, Fierce Feminists and First Ladies of Literature; Ignotofsky, Rachel (2019), Women in Art: 50 Fearless Creatives who Inspired the World; Halligan, Katherine & Walsh, Sarah (2018), HerStory: 50 Women and Girls Who Shook the World. ↩

- The most famous work is certainly that of Alphonse Rebière (1842–1900), Women in science published in 1897. During his lifetime, Rebière had already published in 1889 a brochure on women in mathematics, in which, besides Kovalevskaya, five other contemporary mathematicians were presented. We find there Sophie Germain (1776–1831), first laureate of a prize from the Academy of Sciences of Paris, or Liouba Bortniker (1860–1900), first laureate of the prestigious “aggregation of mathematics” in 1885 and laureate of the first Peccot-Vimont prize a year later (Rebière 1889). In 1894, at a Cercle Saint-Simon conference, he published the first edition/volume of Les Femmes dans les sciences, a prosopography still rather thin, the only novelty compared to the 1889 fascicle being the astronomer and mathematician Mary Sommerville (1780–1872) [38]. The reception is so positive that a new considerably enlarged edition, instead of a fascicle, appears in 1897. Hundreds of women are presented on 400 pages, among which, however, also appear dubious entries, like the mother of Seneca, whose scientific merit – according to Rebière – was her giving birth to the famed philosopher. For the sake of objectivity, there are statements from critics of women’s education, but it is clear that the aim of this publication is to prove by numbers that the female gender is capable of great achievements in the field of science. ↩

- Cooke specifies that it is Roger Liouville (1856–1930), a distant relative of the famous Joseph Liouville (1809–1882), who had already given this proof in 1897. In fact, Liouville published an article believing that ‘it contained the proof. However, it contained serious errors which were known a few years later [2][p.106]. Other results were also obtained with Riemann’s theory, which was rejected by Weierstrass and his school [23]. Other points of the mathematics of Kovalevskaya are evoked in this article http://images.math.cnrs.fr/Les-deux-idees-de-Sofia-Kovalevskaya.html of Images des mathematics. ↩

- At the time, it was widely accepted that geniuses had to be men because of the creativity required for this type of activity. However, Kovalevskaya was also called a genius in other publications, and this was then generally understood to be the cause of her supposed misery. This explanation is also advanced by Laura Marholm, mentioned later in this article, who referred to her as a “female genius”, which again shows how unusual it was for a woman to be called a genius. ↩

- Weakness (Schwachsinn) is understood here in the double sense of physical and mental weakness, like “debility” in the original sense of the term. ↩

- See [21][chapters 2 and 3]. The fact that the marriage of convenience with Vladimir eventually turned into a real marriage is conveniently put aside, especially by Marholm, as if it were irrelevant. ↩

- This term, rather loosely defined, encompasses anything that was considered licentious and, in the broadest sense, non-feminine. ↩

- In fact, there does not appear to be any other source describing Bashkirtseff as ugly. ↩

- As an example for the 18th century, see Il filosofismo delle belle Guiseppe of Cataneos (1753) (see [44][p. 63 and following]). The lasting effect of this pattern can also be seen in the recently concluded TV serial The Big Bang Theory, in which the attractive but not particularly smart blonde Penny is contrasted with the scientist Amy, smart but exactly presented as unattractive. ↩

- The doctorate in absentia appeared in the middle of the 19th century with the introduction of the doctoral certificate. Students could now simply send their theses without participating in a defense. This resulted in a sharp increase in the number of doctorates – between 1832 and 1865, 1,867 doctorates were awarded at the Faculty of Philosophy of Jena, where mathematics was taught, all in absentia except 19. Significant source of income for universities due to the cost of doctorate fees, doctorates in absentia always had the reputation of lowering the scientific level and opening the door to fraud, which was justified in some cases, as evidenced by the agencies which issue the doctorate degree almost free of charge in exchange for the payment of a fee [36]. The decision, to submit Kovalevsakaya’s three theses was made out of fear, that she would have been subjected to an examination too rigorous in a defense, in order to prove the inability of the female gender to pursue university studies. Note that Kovalevskaya’s close friend, Yulia Lermontova (1846–1919), was awarded her doctoral degree in chemistry shortly after her, also at the University of Göttingen. However, unlike Kovalevskaya, she had to pass an oral exam, which she passed brilliantly [46]. ↩