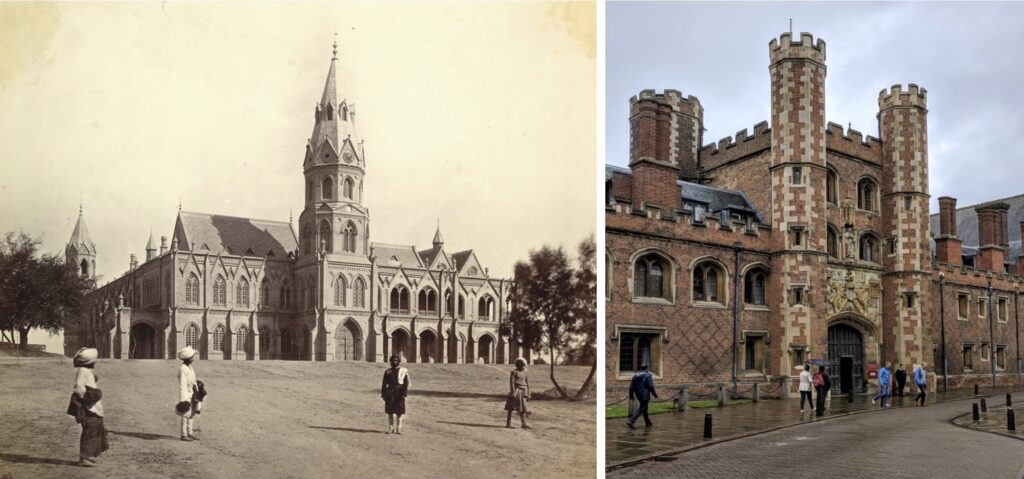

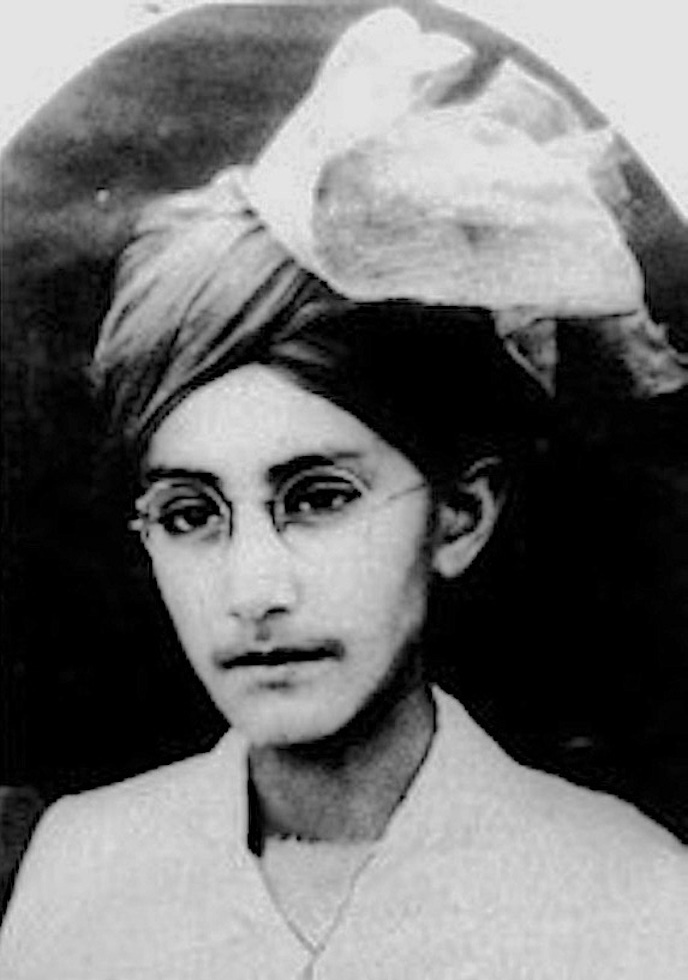

For a long time before the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, Panjab University at Lahore had the responsibility of supervising and coordinating higher education in a large part of north-western India. This part consisted of the present Pakistan (minus the province of Sindh) and the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana and the Union Territory of Chandigarh. Part of this responsibility was to hold the final school examination, called the MSLC or Matriculation and School Leaving Certificate examination. In the Spring of 1940, the results of the MSLC for that year were announced, and they carried the stunning report that a 14-year-old boy, from a remote place called Jhang, had not only topped the examination, but had also obtained a much larger score than all the previous ones. All earlier records had been broken by a great margin. The next day, the leading regional newspaper, the Tribune, with which I now have the privilege of being associated as one of its trustees, carried the picture of a small boy with a large turban. The turban that you saw Salam wearing at the Nobel Prize ceremony is similar to the one he wore in March 1940. And that is the picture that I carry of Salam as I saw him for the first time.

With that kind of performance, he would normally have come to Government College, Lahore, for further studies. But due to a lack of funds, or perhaps other reasons, he continued his studies at Jhang in a small college not known for its greatness. After two years he took the next university examination called the intermediate examination in the Faculty of Arts. He again got the top score.

This group had a subgroup including those who had topped in various examinations and Salam became a leading member of this subgroup. Soon after Salam joined us, one of us, Prem Luthar, got an attack of appendicitis and had to be rushed to the hospital. Salam looked up everything about appendicitis in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and went to Prem’s bedside to help nurse him. In the system, then and now, the hospital relied on attention from friends and relatives to see people through their illnesses there. Salam spent 48 sleepless hours attending to Prem after his surgery. This endeared him to all of us and made him a very close member of the group. Also, his laughter, such vigorous laughter in a small body, made sure that wherever Salam was, there was a lot of friendship.

The academic requirements were no strain on Salam, so he had plenty of free time. He discovered chess, which he started playing fairly well. He tried ping-pong, which he didn’t play well. Then he started participating in debates, and spent more time in so-called frivolous activities than in study. I believe his father came to know of this and asked him to be careful so that his studies did not suffer.

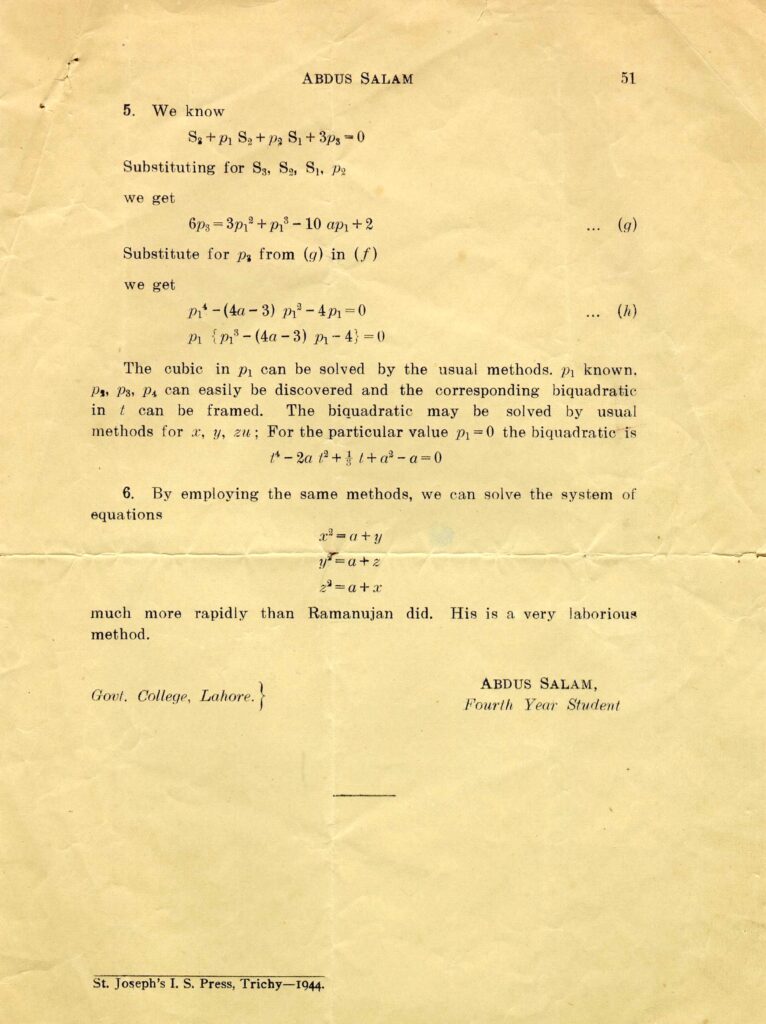

Government College, Lahore, had no pretensions of great scholarship, but among the four teachers of mathematics there was a “strange’’ man called Chowla (whom perhaps many of you know as one of the great number theorists of present times), who was not only, perhaps, the only practising mathematician in the region, but did mathematics all the time and nothing else. The other teachers used to think he was crazy. He had the habit of ending his classes sometimes posing unsolved problems. So, while teaching cubic and quartic equations to Salam’s class, he posed a problem of Ramanujan regarding four simultaneous equations in four variables. Salam spent three or four days on that, and then he came back to Professor Chowla with the solution that the four variables were the roots of a quartic whose coefficients could be found by solving a cubic. Professor Chowla sent Salam’s solution to Mathematics Student for publication. Thus, the first published paper of Salam appeared as a two-page note in volume 11 (1944) of Mathematics Student, pages 50–51. The note has at the end the name and address of the author as Abdus Salam, 4th year student, Government College, Lahore. He was an eighteen-year-old undergraduate at the time in an atmosphere where no one (other than Chowla, of course) thought of doing anything original. The last paragraph in the paper says: “By employing the same methods, we can solve the system of equations x^2 = a+y, y^2 = a+z, z^2 = a+x much more rapidly than Ramanujan did. His is a very laborious method.’’ One cannot but notice the confidence of an undergraduate student talking about an effort of the legendary Ramanujan.

Salam opted for mathematics. I guess he felt that he could prepare English and history at the ICS level on his own, but mathematics would need more training. Since I was one year ahead of him as a student of mathematics, we became closer still. In the meantime, I had also moved to the hostel, so we were neighbours. Neither of us could afford to buy books, so we borrowed them from the library on the clear understanding that each of us could walk into the other’s room and take whatever he needed to study. We exchanged some notes sometimes, but since the system was no strain, neither needed the other’s help academically. Salam’s interest in literature continued and he had a great passion for the beauty of thought, expression and also human form. He discovered Oscar Wilde and for some time he was talking only of the beauty of Oscar Wilde’s language and wit. At one time he was reading Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, a few pages almost every day.

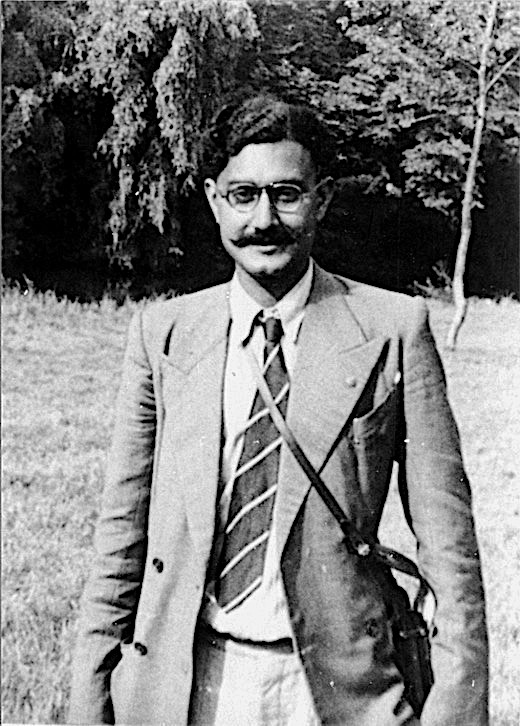

At the beginning of 1948, he passed the Mathematical Tripos Part II with a first. It was rumoured that he had the top score there also, though at Cambridge they did not reveal individual scores. I came to Cambridge in 1948 as a research student and met Salam again. On his advice, with the help of Professor Mordell, my supervisor, I also transferred to St. John’s from Fitzwilliam House where the Indian High Commission had placed me. In the Cambridge system, it was obligatory to have dinners in the college hall, and we had at least five dinners there every week. It was quite natural that Salam and I and a few others started having dinners together because of our common background and language, and this group became very close. We used to walk together, go to movies together, and when we did not feel like working we went to each other’s rooms and talked Punjabi till late hours. After having done Part II of the Mathematical Tripos in two years, Salam joined Natural Sciences Part II. He was miserable in the laboratory and when he took the examination in 1949 he was very apprehensive. But after seeing his result, he came to our rooms to give the good news that he had again got a first. He also described the following amusing incident. He said that after looking at his result at the Senate Hall, he met one of his lab supervisors, who said “Salam, how did you do?’’ Salam said: “Sir, I have managed a first.’’ The man turned a full circle on his feet and he said: “This shows how wrong one can be.’’

Salam had now completed three years of his stay at Cambridge. He had a double first and his scholarship had come to an end. He was planning to go back home, take the Pakistan Civil Service examination and start playing his role as a supporter of his family. Then, Fred Hoyle, I think, told him that the college would like him to stay for research and was willing to give him an exhibition for the purpose. Salam came to our rooms, which Nitya Nand and I were sharing, and said “Look, now what should I do? College is offering me this scholarship. On the other hand, my father is not getting younger, my brothers are growing up, they need my emotional support, and they will need my financial support also. It’s time I went and earned something for my family, and here they’re asking me to stay on for research. I have my obligation to my community also. I would be useful to them if I join the higher Civil Service.’’ (Nitya Nand and I used to discuss our plans and common concerns with him.) We told him: “Salam, Pakistan has many people who would make good administrators, maybe better than you, but it’s hardly likely that there’d be anybody who would be able to make the type of contribution to science that you may be able to make.’’ Salam spent a couple of agonising days and came back to our rooms in the college. He said: “Look, I am going to pack my books and some other things in two trunks and leave them with you. I will go back to Pakistan. If I can manage something which allows me to help my family and also pay my way here, I’ll come back and retrieve these trunks. Otherwise, you ship them back to me through Thomas Cook.’’

He went back. With the help of Sir Zafrulla Khan, I think, he was appointed Professor of Mathematics at Lahore Government College, given leave on full salary to be paid to his father, and sent back to Cambridge to work for his PhD. So he came back and persuaded Kemmer to supervise him. Kemmer told him that he would give him no problems and suggest no solutions, and the only thing that he could expect was that he could talk to him whenever he wanted to. For some time Salam was miserable because he was not able to find any good problems. He used to come to our rooms and use very strong Punjabi expressions telling us that we were his enemies, not friends. We had misguided him, and instead of Salam the successful, now we were meeting Salam the unsuccessful. And that we had done him a great disservice. Very soon he discovered the Thursday Seminar. Matthews, and renormalisation. After that, there was no looking back.

I was going to Princeton in 1950 on the invitation of our old teacher, Professor S.~Chowla, and Salam said: “If you meet Dyson, you tell him that I have renormalised longitudinal photons.’’ I happened to meet Dyson and mentioned this to him. He said: “I don’t believe it, but if he has done it he will be very famous.’’ And he is famous. On my telling Dyson that Salam had taken up this work because of his suggestion in one of his papers, Dyson said: “I had said it should be done, not that it could be done.’’

Salam was elected to a Fellowship of St. John’s College, Cambridge in 1951 and I got elected in 1952. I came to Cambridge in 1954 for residence for a few months. During this time I again had an opportunity to spend a good deal of time with him, often enjoying the hospitality of his wife. Even then Salam had started thinking seriously of taking steps for the development of science in our countries. We both felt that one of the great difficulties for young scientists in our countries was isolation from active workers elsewhere. As we all know, Salam’s motivation for ICTP was to provide a place where young researchers from developing countries could interact with their peers and seniors and leaders of science from all over.

After 1954 we went our different ways. We met occasionally, for short periods, but whenever I met him he forgot his greatness, he forgot his achievements, and he reverted to the old days talking about old friends and the times we had together. When my daughter, who is a mathematical physicist, met him at Trieste, he wrote in her autograph book some very flattering remarks about me. Out of her reverence for Salam, she is willing to consider that I am not entirely useless.

It was my great fortune to be associated with such a nice human being who was one of the greatest contributions to mankind from our part of the world, and I am grateful to you for letting me pay my tribute to him.\blacksquare