|

|

The non-British Jesuits from France had already arrived and settled on Indian soil in Srirampur, Chandan Nagar and Pondicherry. Among them were astronomers like Father Richaud who installed a 12-foot telescope in Pondicherry in 1689. There was also Claude Boudier who assisted Raja Sawai Jai Singh in setting up telescopes in Jaipur in the year 1730. These served as strong roots of non-British European science in India. Indian science and mathematics education owes a lot to these Jesuit priests who were posted to educational institutions in different provinces in India before Independence. They mentored a whole generation of modern-day scientists and mathematicians by their sheer dedication to honing the talent of young Indian students and giving them the right exposure to world-class science and mathematics education.

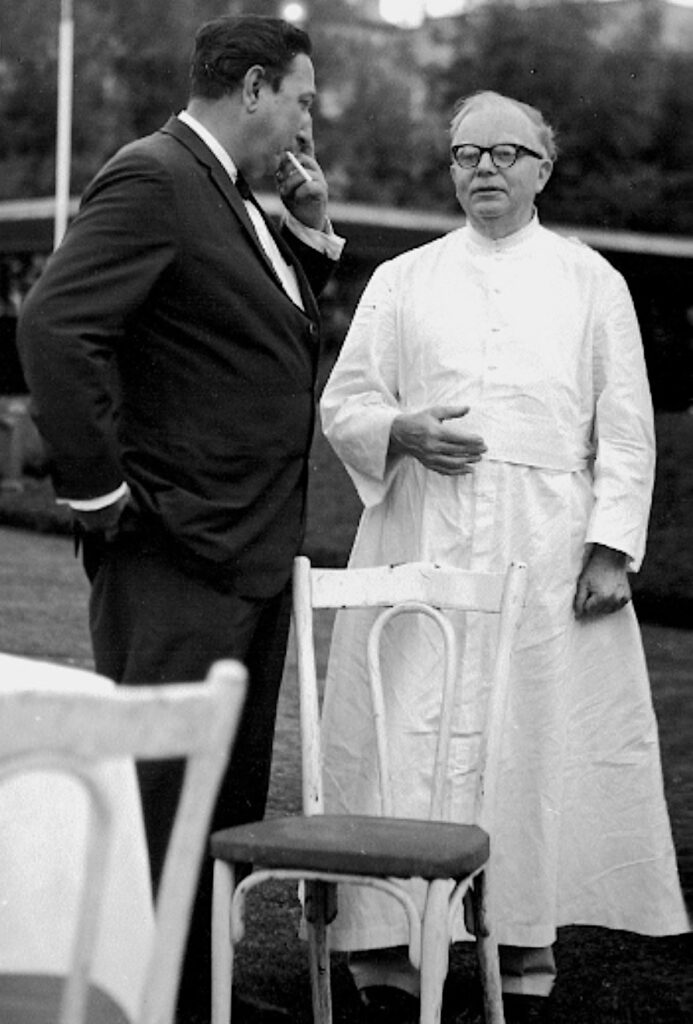

One of them is Father Charles Racine, whose 125th birth anniversary falls this year. This is an occasion that inspires us to look into roles of non-British Jesuits, and the present article touches upon, in some detail, the contribution of two such Jesuits—Father Charles Racine and Father Eugène Lafont—who have left a lasting impact in the way they brought certain refreshing novel elements to education in India.

Father Charles Racine—Mathematician, mentor par excellence

Father Racine of Loyola College in Chennai (the erstwhile Madras), India, was one such ordinary Jesuit priest who was posted to the Indian shores, but proved to be an extraordinary mathematician-mentor who groomed a whole league of top-notch mathematicians who were instrumental in not only establishing modern mathematics research departments in places such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, the Institute of Mathematical Sciences and more, but who also won laurels in their respective fields.

How could a Jesuit priest manage to ignite interest in so many brilliant minds, that too in the field of mathematics, which was considered difficult, unglamorous, and was itself undergoing a lot of transformation?

Two of his legendary students, M.S. Narasimhan and C.S. Seshadri, who happened to be batchmates at Loyola College, Chennai, both concurred while recalling their college days memories that Fr. Racine was not a great teacher who taught mathematics in a traditional manner, but rather that he was very good at spotting young talents, and often gave them access to interesting problems and textbooks (new textbooks from France, thanks to the Bourbaki movement) beyond their regular curriculum. This would stimulate them to go deeper into the field. Even if he wasn’t teaching a course, he would keep track of their progress and recommend them to appropriate research institutes for further studies. They have recalled that often during the designated moral science class, he would engage them in learning mathematics or solving interesting problems. He would be watchful about the difficult circumstances of his students as well, and would often offer whatever assistance possible, as a true mentor.

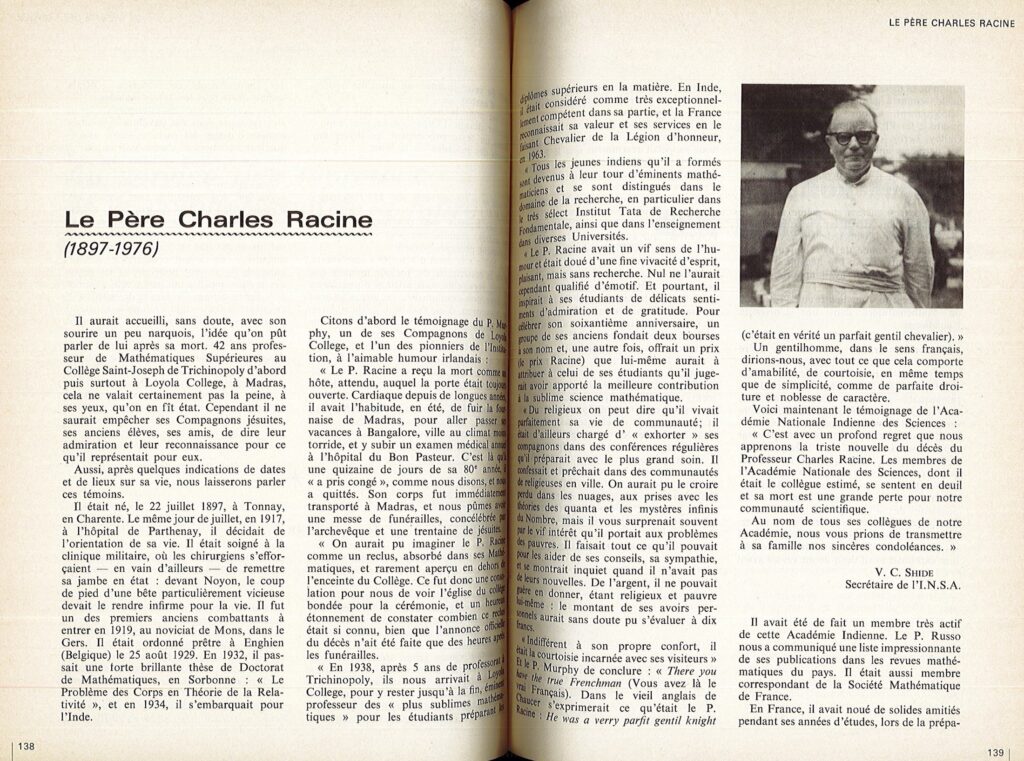

It is rather unfortunate that, though a legion of great mathematicians mentions Fr. Racine as their mentor, there is very little that is known about him, his childhood, or how he got assigned to teaching jobs in southern India. Narasimhan had this great wish to commemorate the 125th birth anniversary of Fr. Racine in memory of his service towards laying a solid foundation for modern mathematics in India, and inspiring a whole generation to take up research in one of the most challenging fields. Unfortunately, we lost Narasimhan last year, but his enthusiasm, contacts and the references shared by him, as well as the Jesuit Society headquarters in France and other important resources, including Racine’s own Ph.D. thesis provided by Michel Waldschmidt, did help in unravelling certain aspects of the quiet ascetic life of Fr. Racine.

Early Life

Father Racine was born on 22nd July 1897 in Tonnay-Charente – a commune in the Charente-Maritime department under the administrative region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France. Though not much is known about his early childhood and growing-up years, available documents inform that before he was twenty he had enlisted in the army during World War I in 1916. Rather unluckily, he sustained a serious leg injury, on his twentieth birthday, apparently by the kick of a Gallican artillery mule. Due to this injury, he had to walk with a limp and live with pain his entire life, but the incident also spared him from serving during World War II. It could not, however, diminish his passion for teaching, as in his advanced years, in order to reduce much movement he decided to have a blackboard installed in one of the outside rooms where he continued with his private tutoring for those who came seeking his help.

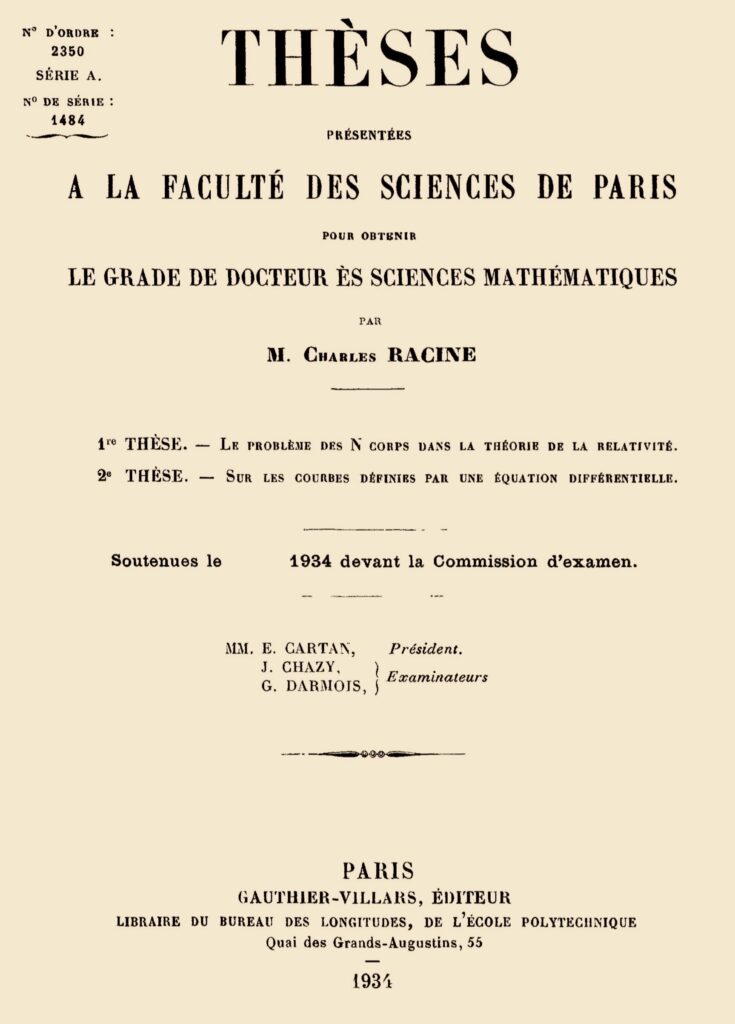

His sufferings during the war may have been instrumental in his decision to enter religious noviceship in 1919 at Mons, Gers. He first opted for the Redemptorists,3 but was encouraged to join the Jesuits as they were more open and welcoming to young men. He was ordained as a Jesuit priest at Enghien, Belgium, on 25th August 1929. Before becoming a Jesuit, he pursued his real passion, which was mathematics. He taught mathematics for a year in Sarlat, and then went to Paris to get his license for teaching between 1924 and 1926. He studied theology in Innsbruck and Enghien (1927 to 1930). After being ordained in 1929, he completed his PhD thesis in 1934 under the guidance of none other than Élie Cartan, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century.

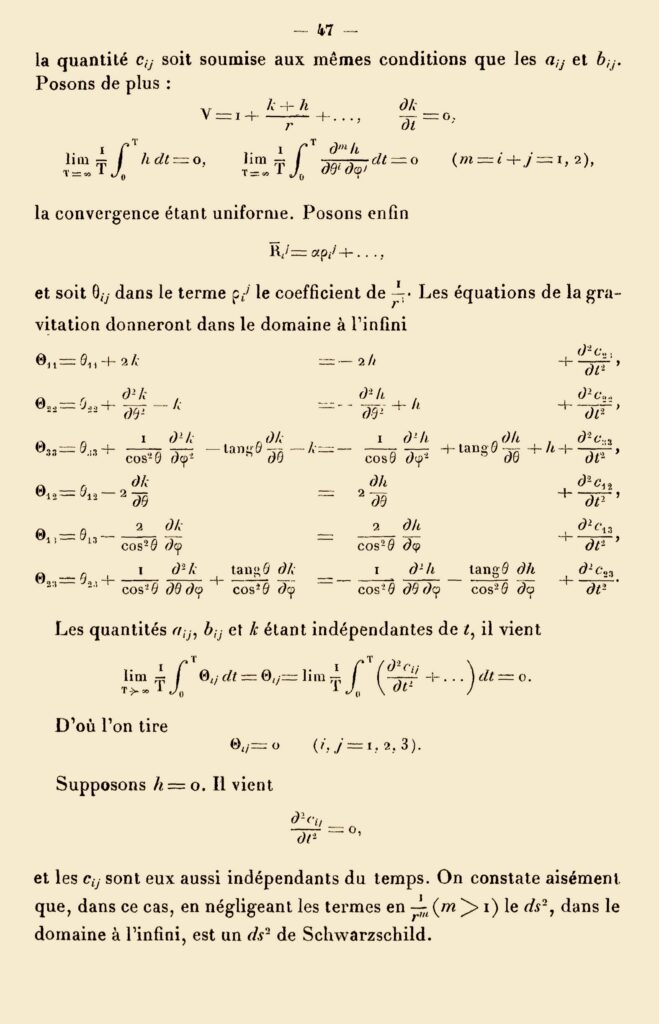

Back then, to become `Docteur d’État’ (Doctor of State) in Mathematics, it was necessary for the candidate to submit two theses. The first one was the main one that included new results, which in the case of Fr. Racine was the work titled Le problème des N corps dans la théorie de la relativité (The N-body problem in the theory of relativity). The so-called `second thesis’ was only to demonstrate that the candidate was able to deliver a lecture on a different topic; for Fr. Racine, the topic was Sur les courbes définies par une équation différentielle (On the curves defined by a differential equation). It was often called `Propositions données par la Faculté’ (Propositions given by the Faculty). The second thesis was not supposed to be published, and only the title was mentioned, as seen on the cover page of Racine’s thesis.

The rules that governed the process then go back to 1808, changed only a little after that, and were essentially in force until 1984. In the reform of 1984, the Doctorat de troisième cycle (postgraduate doctorate), was succeeded by a unified doctoral diploma, and the Doctorat d’état was succeeded by the Habilitation à diriger des recherches (HDR). The HDR, though not a second doctorate, is the highest diploma that can be obtained in the French university system, and is necessary in order to be eligible to supervise PhD students.

In the introduction to his first thesis, Fr. Racine summarizes the essential features as follows:

In 1934, Fr. Racine left for India, probably enlisted to the Madurai Mission, thanks to Fr. Bertram who had a great influence on him. He came to Kodaikanal in 1935 for his Tertianship5 and went on to join St. Joseph’s College in Thiruchirapalli.

|

|

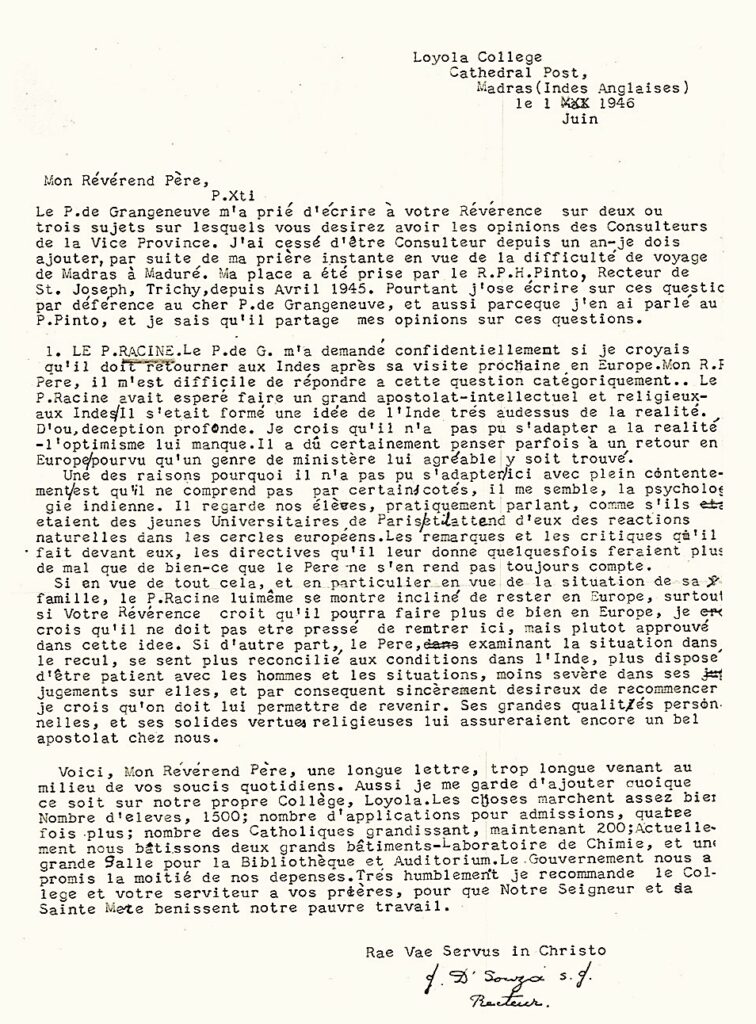

He moved to Loyola College, Madras, in 1939 and stayed there even after his retirement until his death on 5th August 1976. In the intermediate years, he visited Europe twice (once when his sister and her husband died tragically in a road accident, and another time for a much needed holiday). In a rare communique from 1946 shared by the headquarters of the Jesuits’ society, there is a curious remark by his superior that maybe India did not suit Fr. Racine and that he did not understand the psychology of Indian students as he often regarded them as equivalent to students in Paris, introducing them to new radical mathematical methods which were different from traditional British mathematics. He further added that Fr. Racine clearly was not able to adapt to the harsh realities of India and should return to Europe as soon as an agreeable replacement was found. It is not clear whether these were Fr. Racine’s thoughts as well but the fact is, he continued to live in Madras doing what he did best—teaching mathematics unconventionally and treating students as equal to their peers in any part of the world.

Fr. Racine was perceived by many as a recluse, but certainly not so by his students. He kept in touch with all his students, helped them during their difficult times and often would send the young and talented to the senior and established ones, thus establishing a thriving ecosystem of mathematicians who went on to collaborate and study in some of the best places in the world. On his 60th birthday, his former students founded two scholarships under his name, and a prize he could award to students with the best contributions to mathematical sciences. In 1963, he was awarded Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour) , the highest civilian award by the French Government for his contribution to education and society.

Even indirectly so, Fr. Racine resides in the fond and warm memories of many students of the time who studied in Madras (and not necessarily in Loyola College) as is evident in the following recollections of another distinguished mathematician Bhama Srinivasan:

One of the available obituaries mentions the life obligations of a Jesuit priest:

|

|

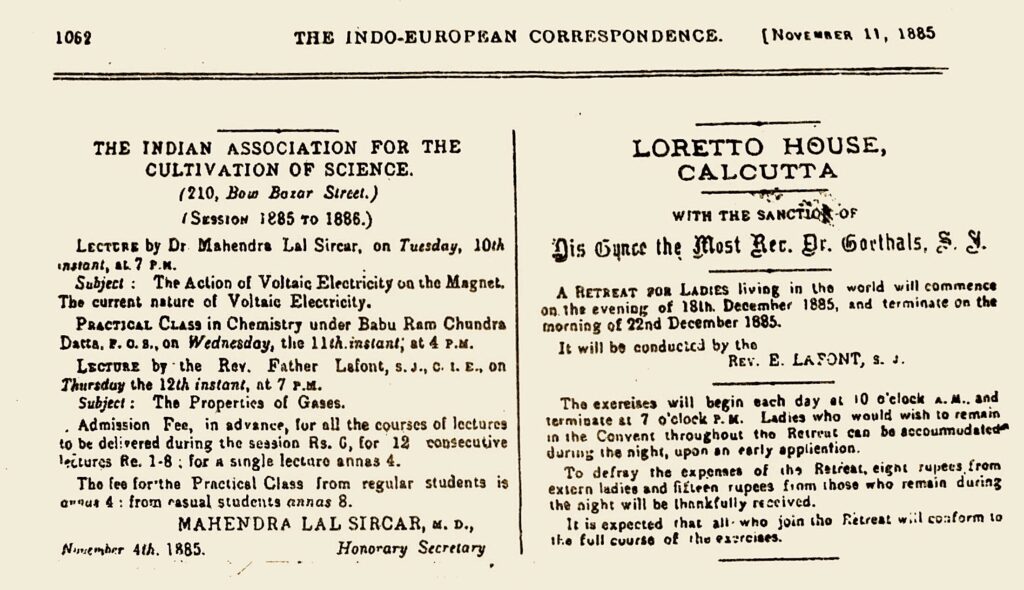

Father Eugène Lafont—A pioneer of modern science education8

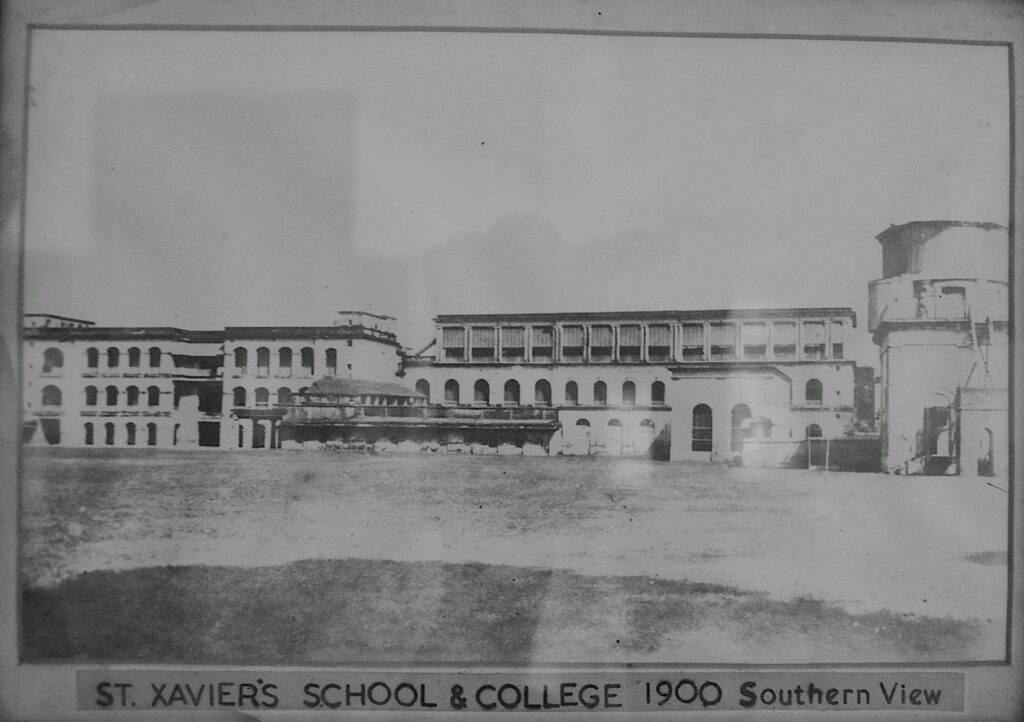

The St. Xavier’s Institution established in 1860 at Park Street’s famous address where Sans Souci theatre once stood has had many luminaries on its rolls. Right from its inception, St. Xavier’s college had a vision of imparting the best European education to catholic settlers in the city along with the locals. The first prospectus clearly stated, “The course of studies is similar to that pursued in the great colleges of Europe” and it included subjects like mathematics, trigonometry, and the natural sciences. But no one had envisioned that their new faculty, Father Eugène Lafont, who joined the institution on 7th December 1865, would develop an unparalleled blueprint for the science education movement not just for the city, but for Bengal and India in collaboration with Mahendralal Sircar. Who was this young man who gave up his scientific pursuit in Belgium, to take up the lifelong mission of laying the foundation of science education in a faraway colonial land?

Eugène Lafont S.J. was born on 26th March 1837 in Mons, Hainaut in Belgium. He completed his secondary studies in Jesuit College de Sainte-Barbe and entered a Jesuit formation in the Society of Jesus. He taught in Jesuit schools in Ghent (1857–59) and Liège (1862–63). He completed his studies in both philosophy (in Tournai) and natural sciences (in Namur). However, he had a natural inclination towards the experimental sciences. When in 1859, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus chose the Jesuit Province of Belgium for their noble mission of opening a college for native Catholics in Bengal, the task was entrusted to Henri Depelchin who belonged to the Jesuit community of Namur. Being from Namur, Henri Depelchin knew about Eugène Lafont’s passion for natural sciences and so, on his request, Lafont was assigned to the newly founded St. Xavier’s institution in 1865 to teach science.

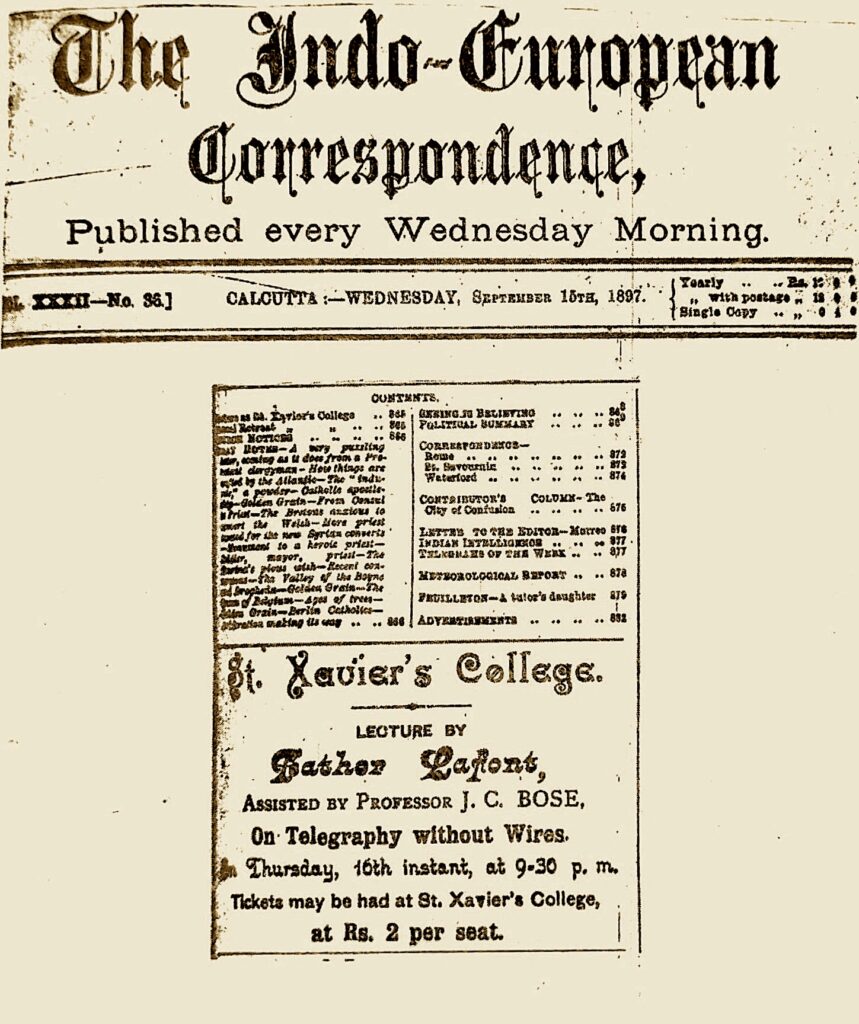

Being inclined towards experimentation, Father Lafont immediately prioritized setting up a laboratory on the college rooftop. It was the first of its kind in India which soon came into the limelight in 1867 when he made a prediction about a devastating cyclone that was approaching the city, based on his regular meteorological observations carried out using a barometer in his rooftop lab. He immediately informed the local British government authorities who had missed it. Thanks to him, immediate measures were taken to save lives. Thus, he became a new reliable scientific weather forecaster for the Indo-European Correspondence, the weekly newspaper that was published in Calcutta.

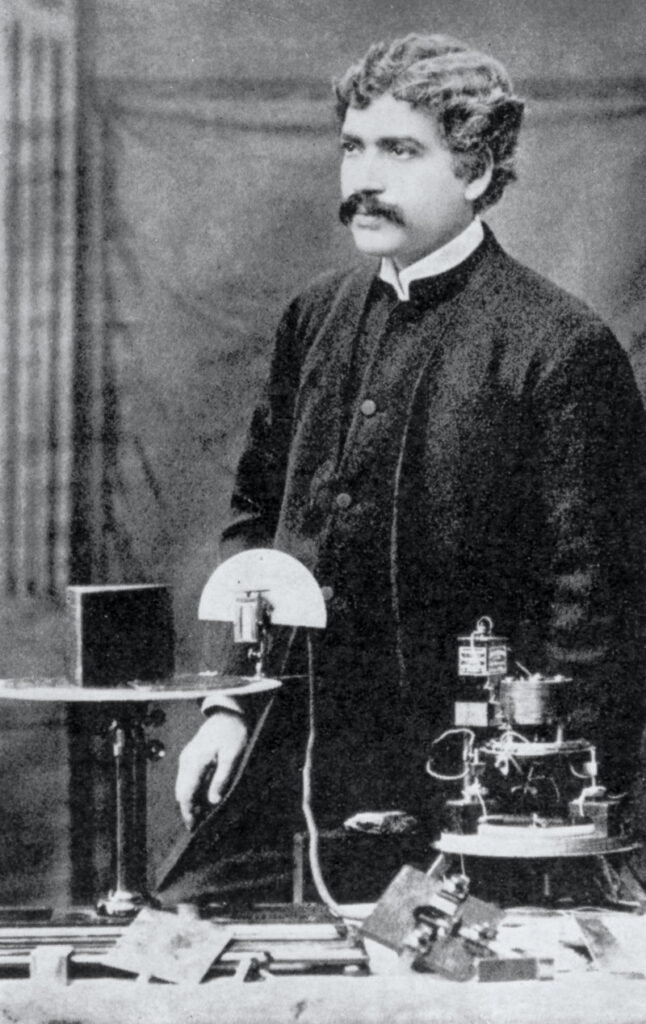

Fr. Lafont probably knew that it was not easy to lure students towards the natural sciences without fascinating them with new discoveries and hands-on experisments. He was highly determined to educate common people about science and the scientific approach. Being aware of the Royal Institution of England and its tradition of science lectures and demonstrations, he started organizing weekly science lectures for the public in which he demonstrated some amazing science experiments. One of his first science lectures was on the so-called “magic lantern” which may as well have been the first instance of a projection technique being used in lectures in India. Thus began Bengal’s and India’s tryst with modern science. Father Lafont started raising funds through these lectures to build his laboratory. He often travelled to the Paris exhibition to procure the latest scientific equipment. His hands-on demonstration and lecturing technique yielded results when they ignited a passion in students like the young Jagadish Chandra Bose, Prafulla Chandra Ray and P.N. Bose. When Mahendralal Sircar decided to build the Indian Association for Cultivation of Science, one of its founding members was Father Lafont.

Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose, as we know him now, was one of his most notable students who went for higher studies abroad in 1880 on the recommendation of Fr. Lafont. Bose went on to discover micro/millimetre waves and wireless communication, which he demonstrated both in Presidency College and later in Town Hall, in the presence of the then Governor of Bengal through a simple experiment in 1894. The latter lecture demonstration was arranged by Fr. Lafont to ensure Bose got his due recognition as the pioneer of wireless communication.

|

|

||

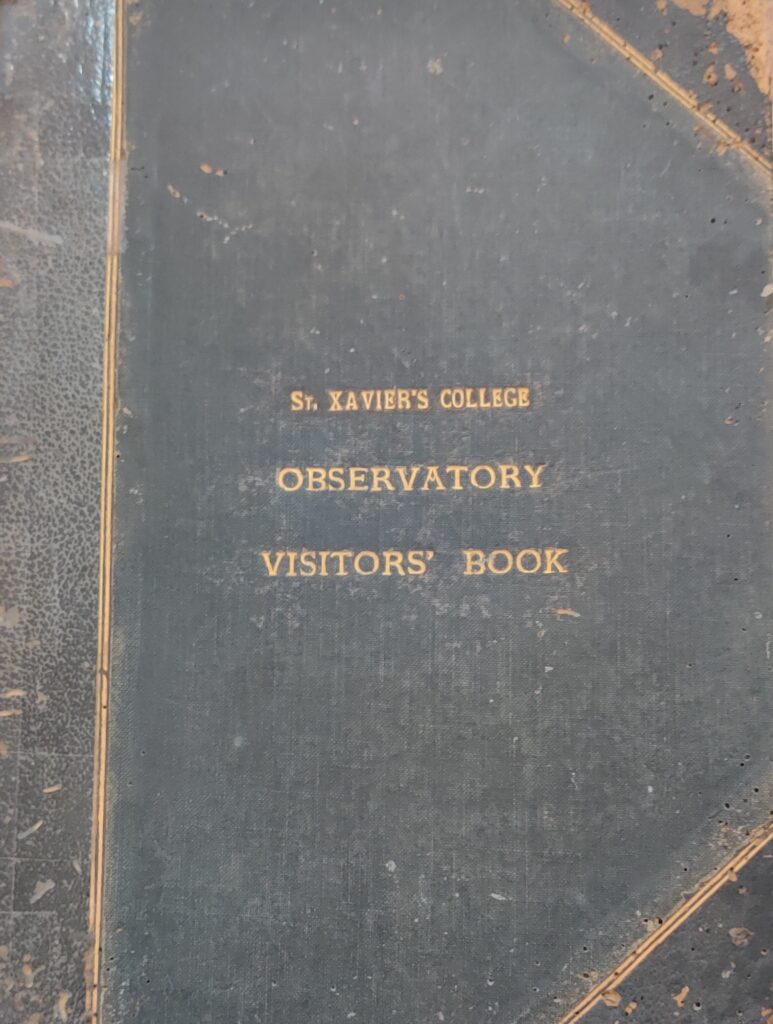

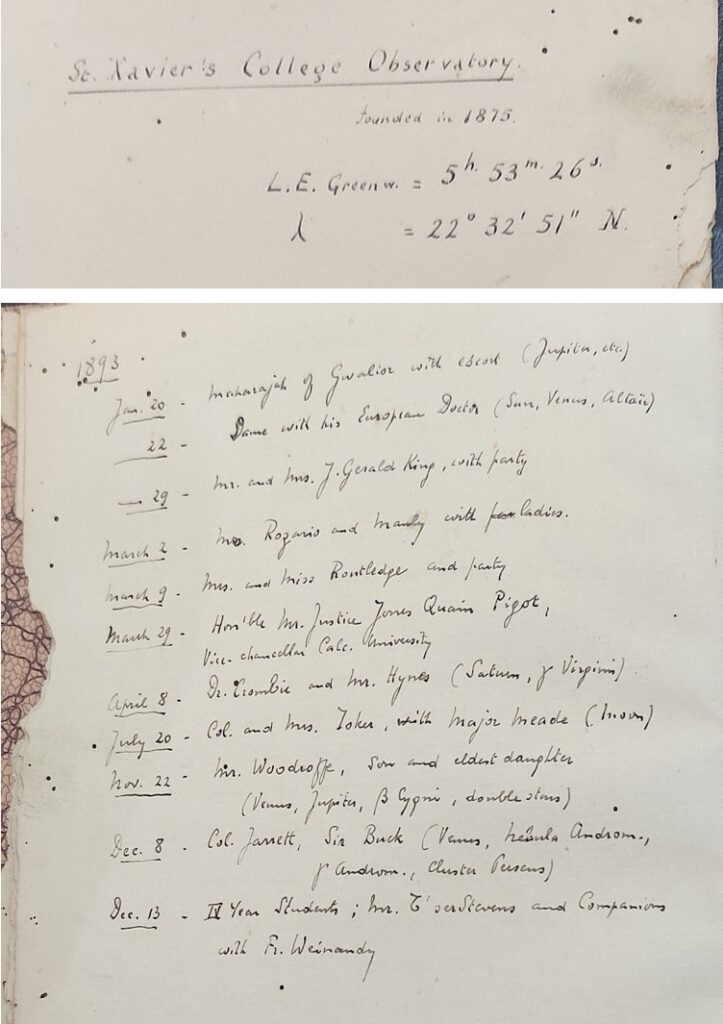

| Left side photo shows the cover page of the logbook record of visitors to the observatory maintained by Fr. Lafont since its inception in 1875. The right side photo shows some samples of the visitor entries, that includes the Maharaja of Gwalior. St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata | |||

Fr.Lafont was often asked how he reconciled religion with science. He would reply with a candour that there was no contradiction between the two truths of life because he never pitted one against the other. Even after renouncing his responsibility as Rector of St. Xavier’s college, he continued to teach physics and built his laboratory which he envisioned as a museum with the best scientific equipment. He slowly shifted focus from his science lectures and IACS towards basic science research. Coincidentally, the last meeting that he presided at IACS in 1907, was the meeting in which C.V. Raman was introduced as a new member. It is not known whether they both met but Fr. Lafont did hand over the baton, and the fertile ground he had created to brilliant young scientists, who went on to bring glory to India.

The institution that he helped to build still carries forward his legacy. The rooftop solar observatory of St. Xavier’s college was renovated and restored in 2014. It has been renamed and dedicated to Fr. Lafont and there are plans to have regular collaborative projects which will benefit students and young researchers. Both St. Xavier’s Collegiate School and College continue to groom and produce top scientific talent. The alumni of the physics department currently play an important role in scientific establishments across the country and abroad. Like they say, candle to candle, the flame lit by Fr. Lafont’s magic lantern continues to illuminate many young minds.

The obituary published in Nature on 14th May 1908 says: “Father Lafont was a born scientific lecturer and had a peculiar facility for putting dry facts in a popular way and an equal facility for making his lectures interesting by excellent experimental illustrations.” Perpetuating this art and initiative to take science to a wider populace would be a fitting tribute to commemorate his legacy. \blacksquare

Acknowledgement Our deep gratitude to Michel Waldschmidt of Sorbonne University for helping us collate important resources from the Jesuits’ Archives and Academy of Sciences in Paris about the early life of Fr. Racine, his PhD thesis and other academic contributions. We would also like to extend our thanks to Jesuits’ Archives for sharing their rare archival materials with us. We would like to acknowledge Rev. Fr. Dominic Savio, SJ Principal of St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata and Live History India, for providing requisite permissions. Our gratitude to Shibaji Banerjee, Assistant Director and Bappaditya Manna, the Observatory officer of St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata for the guided access to the FELO premises and archives. Thanks are also due to Joseph Prabagar of Loyola college Chennai and Prabir Sen of Darjeeling Government College who went the extra mile to locate, visit and click photographs of the final resting places of Fr. Racine and Fr. Lafont. My sincere gratitude to C.S. Aravinda for his encouragement, valuable inputs and to the brilliant team of Bhāvanā for meticulous editing with attention to the minutest details. Lastly, a very special thanks to my son Anuran for the translation of archival text from French to English and to Vishwambhar Pati for introducing me to C.S. Aravinda without which this article wouldn’t have materialized.

Footnotes

- The Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits, is a religious order of the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded by Ignatius of Loyola and six companions, with the approval of Pope Paul III in 1540. ↩

- Swami Vivekananda in America New Discoveries, by Marie Louis Burke, First Edition 1958, published by Vedanta Society of Northern California, San Francisco, pp. 255. ↩

- The Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, commonly known as the Redemptorists, is a religious congregation of the Catholic Church, dedicated to missionary work and founded by Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), at Scala, near Amalfi in Italy, for the purpose of labouring among neglected country people around Naples. Members of the congregation are Catholic priests and consecrated religious brothers and ministers in more than 100 countries. ↩

- This probably means that consideration beyond the limits of a bounded region is possible. ↩

- The Tertianship is the final period of formation for members of the Society of Jesus. Upon the invitation of the Provincial, it usually begins three to five years after the completion of graduate studies.. ↩

- This interview, conducted during the pandemic on 14th February 2021, was probably one of his last interviews. ↩

- Apparently, when he died he had a mere 10 francs to his name. ↩

- This part of the article is a substantially revised version of the article published by the author in Live History of India on 14th September 2020, the link to which is: https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/people/father-lafont. ↩

- In a technique known as Transit Spectroscopy, it is possible to extract information about the constituents of a transiting planet’s atmosphere from the spectroscopic analysis of the starlight passing through it. For more details, see: https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/discovery/how-we-find-and-characterize/. ↩

- It was an organization founded by a Bengali aristocrat, Nawab Abdul Latif in 1863 with a goal of educating Muslim youth in English medium schools and developing in them European social outlook. ↩