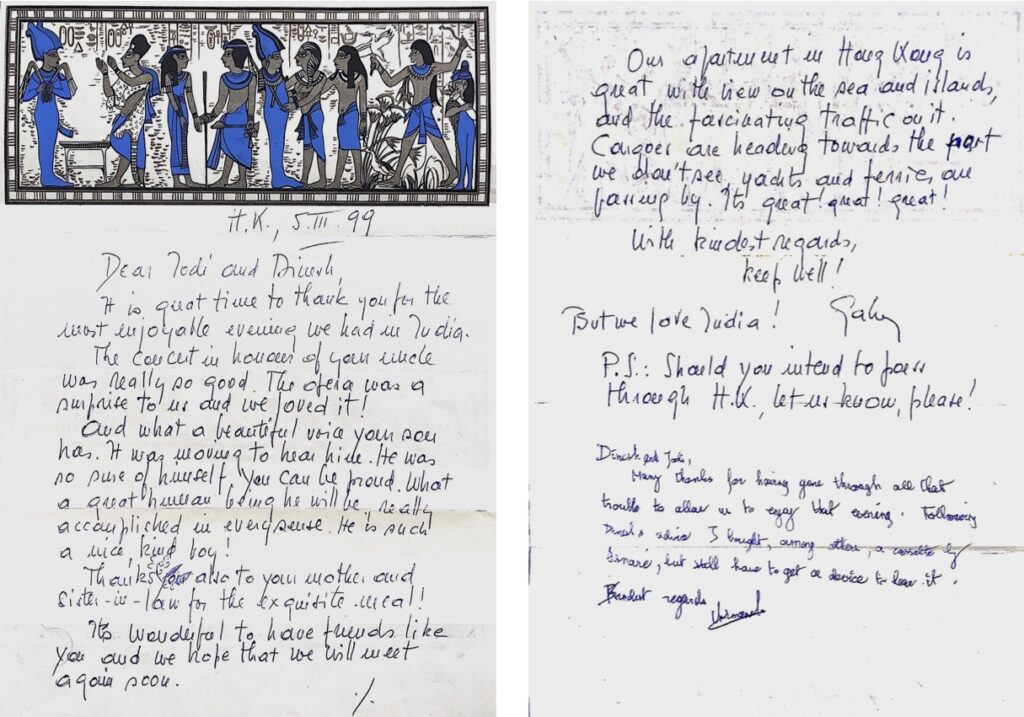

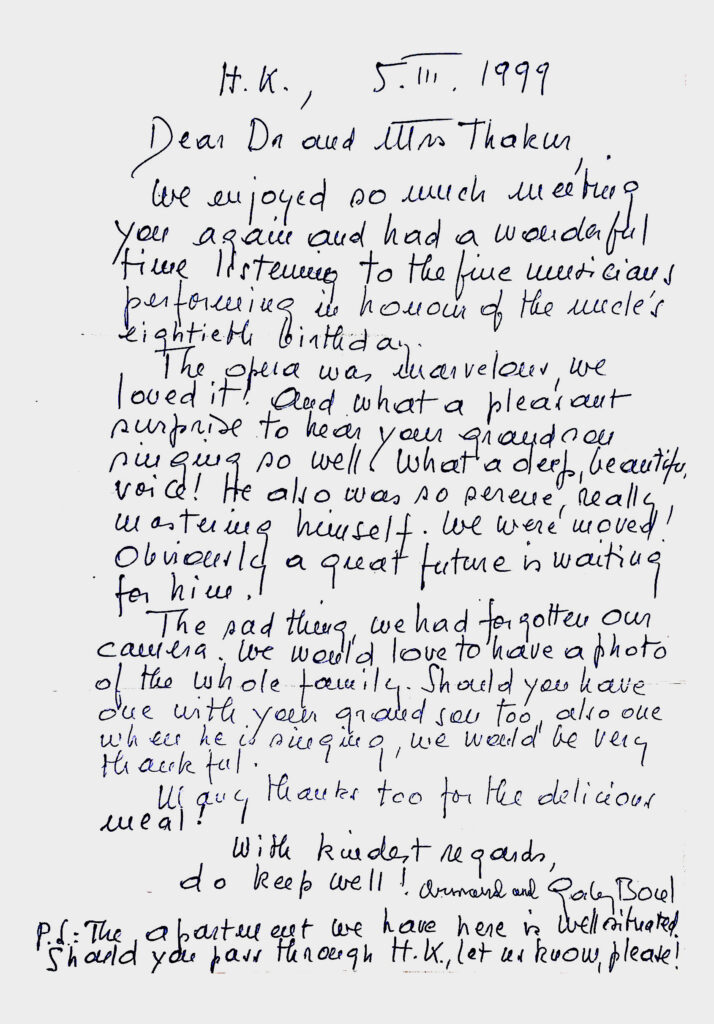

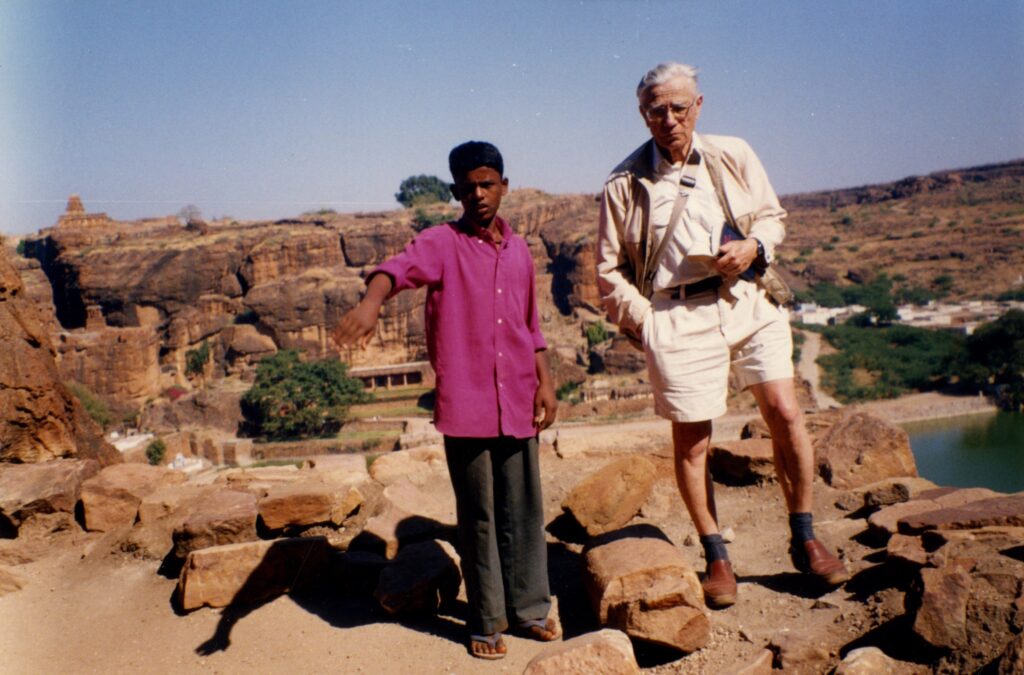

The tribute offered here dwells on an aspect that was an integral part of him as a person: a deep and abiding interest in the arts, culture and history. In this, he was equally well-complemented by his ever enthusiastic wife Gaby, as she was fondly known, who accompanied him wherever he travelled. Appreciation of music and art took the Borels all over the world. India was one of their favourite destinations where they got to meet and understand the land’s rich musical and artistic heritage. Ever open to authentic cultural experiences, they happily stayed and travelled with their Indian friends – enjoying the cultural diversity. After their visits concluded, both Armand and Gaby Borel would write letters thanking their hosts, and recalling the great times spent in each other’s company, and the further forging of already strong bonds of friendship.

Walking on its quiet and lush avenues, with a soothing sun filtering through the canopy of tall trees of the sylvan campus of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, it is easy for a first-time visitor to feel a sense of both awe and anticipation. Awe arises from being in a place that has been home uninterruptedly to some of the deepest thinkers for the last nine decades since its inception. Anticipation on the other hand, from knowing that the institute’s worthy inhabitants, whose scientific legacy has dramatically shaped the destiny of human life, could be just a few weeks away from breakthroughs that could herald changes to the very manner in which humans think, work, and even live. Few places have had such a large impact on the world outside, as IAS. Mathematics, Natural Sciences, Historical Studies, and Social Sciences constitute the four broad areas of study, or Schools as they are called. It was in the School of Mathematics that Armand Borel, one of the giants of 20th century mathematics, spent a total of 46 years (in addition to his longer visits earlier) starting from 1957 till his passing away in 2003.

As an adolescent, Borel picked up a serious interest in music, in particular jazz. Coming to the USA in the `50s offered him a golden opportunity to continue his interest in jazz. The times he spent at Chicago and New York, both cities having a thriving culture of jazz, catered to his appetite to explore deeper. As his elder daughter Dominique fondly recollects: “There was always music playing in our home. Growing up, I recall that there was music in the background every night as I went to sleep.”

The Borel household was managed by the lively personality of his wife Gaby. Borel himself, while being mostly involved in mathematical research, would carve out time to pursue his interests outside of mathematics. In whatever pursuit he undertook that caught his interest, Borel went into it intensely, exploring the finer nuances and revelling in them. Art and culture complemented his academic life. His scholarly inner persona, coupled with his steely determination to unravel and discover things, ensured that he came into contact with some truly gifted artists of his time. Two such artists from India that the Borels met with, and with whom they forged lifelong friendships, are the classical dancer Malavika Sarukkai, and the flute artist Shashank Subramanyam. In accompanying individual pieces, both Malavika and Shashank recount their experiences of meeting the Borels for the first time, and how those meetings evolved and blossomed into a friendship that grew stronger with time.

Immersed in the arts

Dinesh Thakur

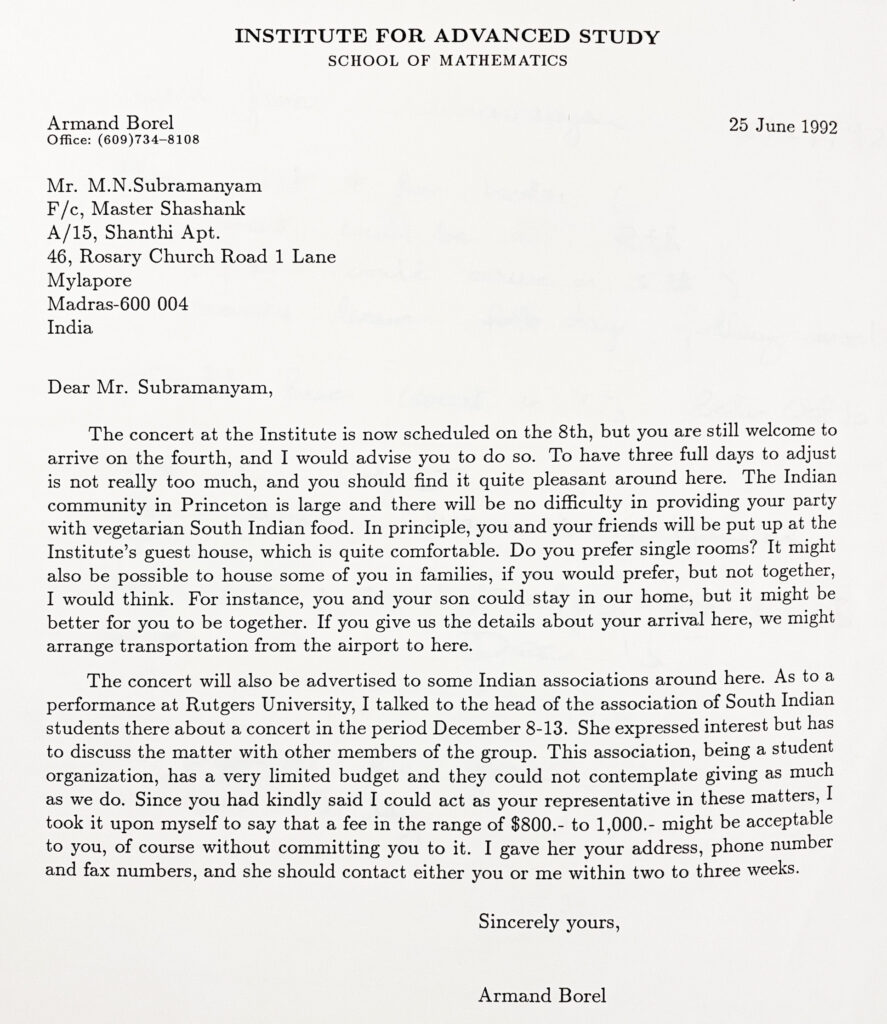

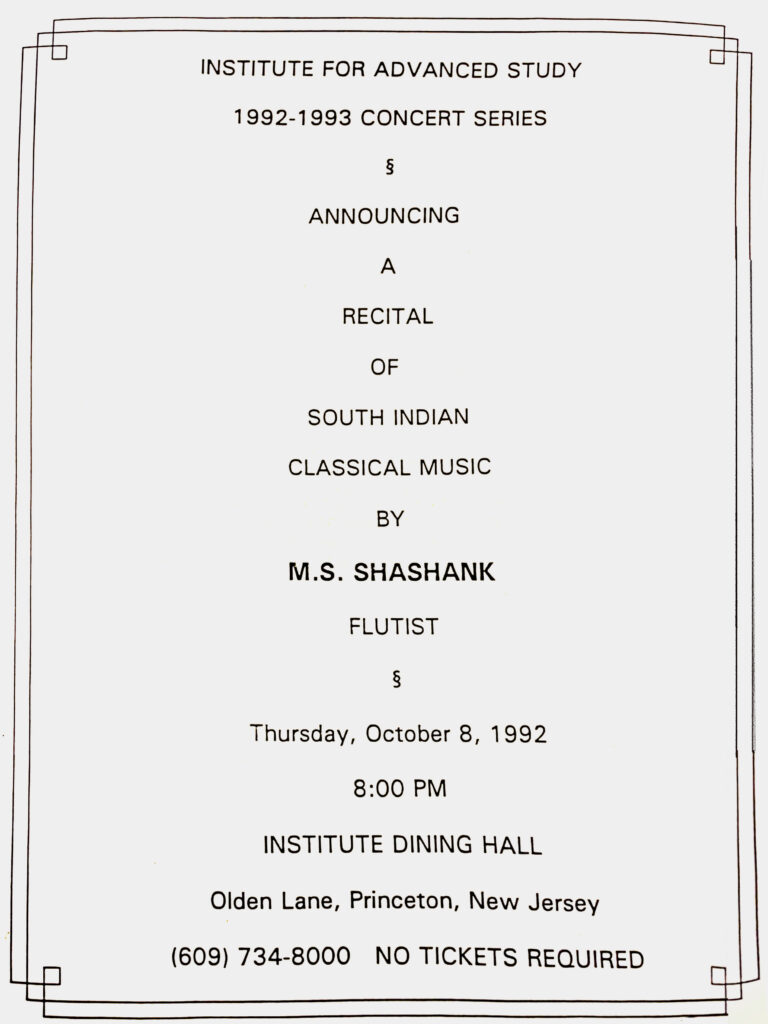

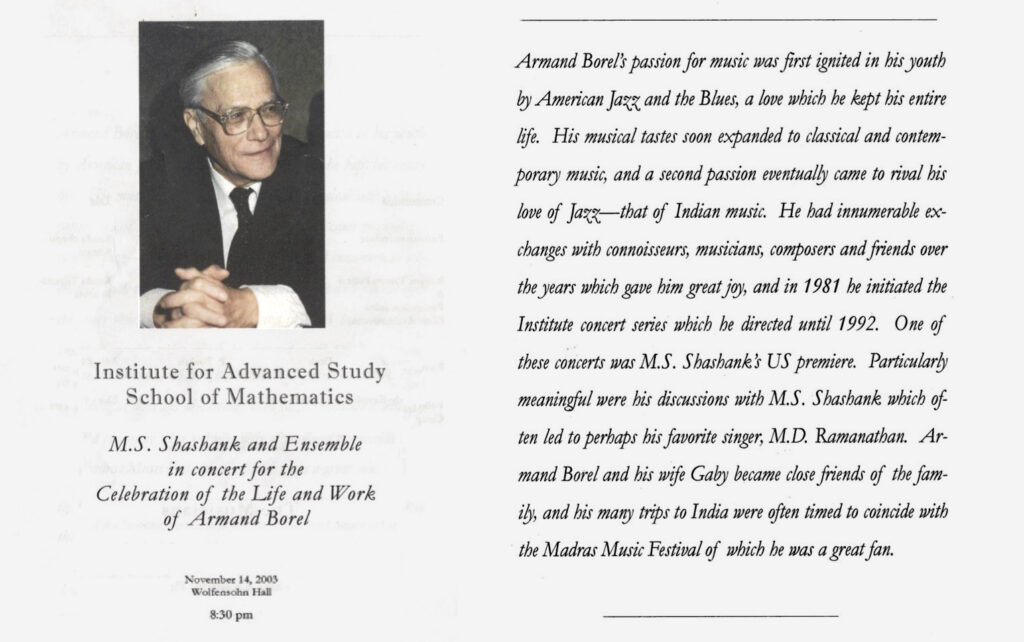

It was this belief in encouraging young talent that led him to offer Shashank Subramanyam, then still a precocious teenage flutist, his very first concert at IAS. As his daughter Dominique recalls, this program that he conceptualized and initiated in the year 1981 at IAS was very meaningful to her father. He produced and directed the program for many years. Shashank Subramanyam and Malavika Sarukkai visited and performed at IAS supported by this program. It was a natural outgrowth of Borel’s holistic view of the role played by the interlacing of the humanities and sciences towards enriching the human experience. In his mind, the arts and the sciences both reinforced and complemented each other harmoniously – an attribute that many of his friends and colleagues admired in him.

Reflecting on the breadth of Borel’s mathematical accomplishments and wide-ranging interest in the arts and culture, Enrico Bombieri, his illustrious mathematical colleague at IAS, expresses his sentiments in the following words.2

Reminiscences of an Enduring Friendship

by Malavika Sarukkai

I have danced and performed for over five decades, and in the course of time have had the good fortune of meeting some extraordinary people like the Borels. My city, then known as Madras, on the eastern coast of India, boasts of a cultural festival called the “December Season”.3 This festival happens in the month when Madras experiences “winter”, a time of year when there happens to be a nip in the air. Unused to this (as this part of India has only three seasons: hot, hotter, and hottest) the locals welcome the season by bringing out their sweaters, shawls, mufflers and ear muffs to keep away the chill in the air. What is special during this time of the year is the interest in people to witness dance and music programs. The festivities are infectious and the locals become acutely aware of their cultural heritage. In turn, they take it upon themselves to attend classical dance and music programs that spring up in every possible performance space in their city.

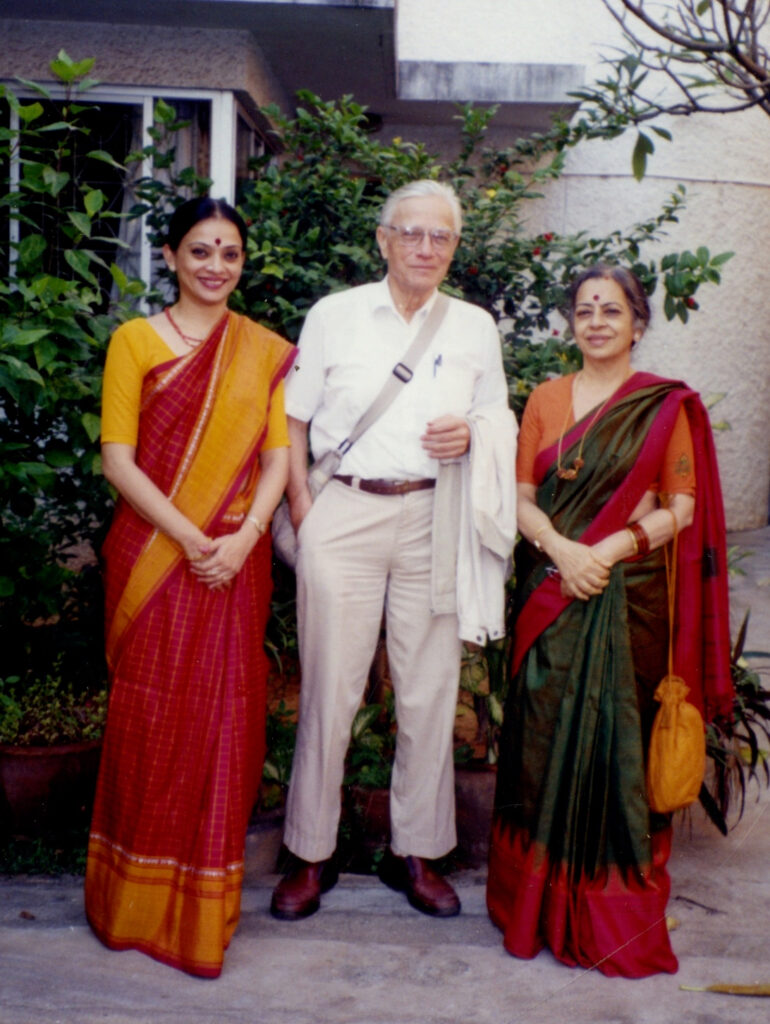

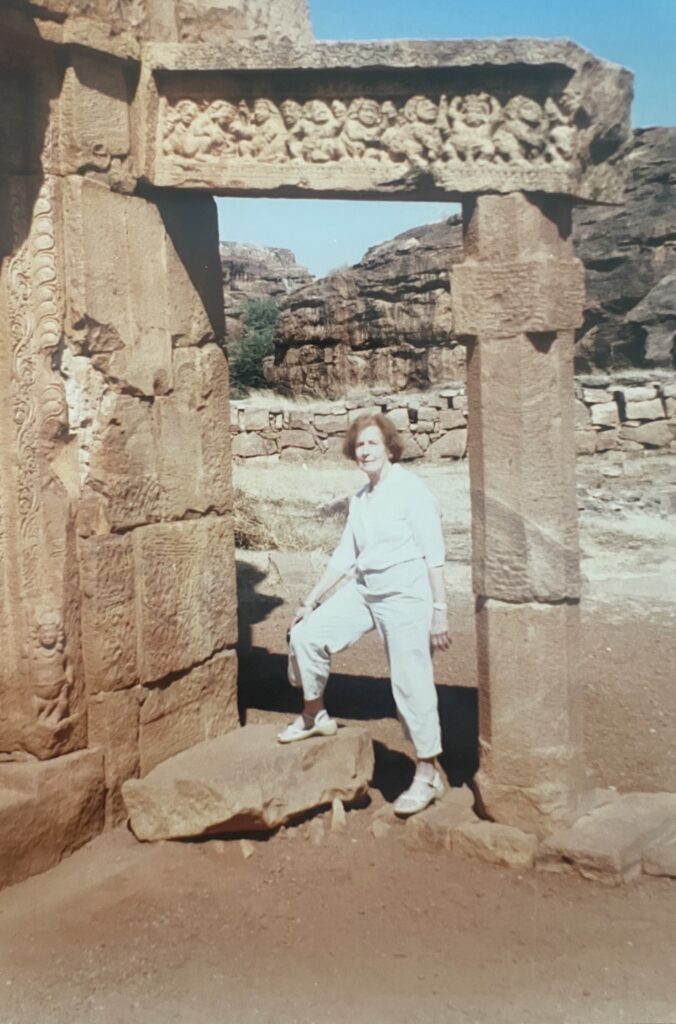

Our paths crossed again and again, every season, whenever the Borels would visit Madras. It was something that both my mother and I keenly looked forward to every December. Often, the Borels would come over for a meal or a coffee to our home. Our conversations whenever we met were intense, almost as if we had no time to lose. For it is not often that we meet people from abroad with such an enduring interest in India, and its classical dance forms. In one of our conversations, the topic of visiting temples in South India came up and immediately there was an enthusiastic clamour to make it happen. Naturally, my mother was best equipped to set up this tour for the four of us on the Borels’ next visit to India – a challenge she readily took up, funnelled by her deep interests in history, myth, iconography and philosophy.

And so it was, that on one visit, the four of us set off on a “templing” visit in South India, the highlight being a visit to the two Siva temples in Thanjavur and Darasuram. Planning a trip in South India had to be done in the optimum month, when we had to avoid both the rains and the heat. However, that year the rains were unseasonal, as was the heat. I remember times when the heat of the temple stones had all of us scurrying across barefoot with a hop, skip, and a run to reach the comfort of the shade. It was fun!

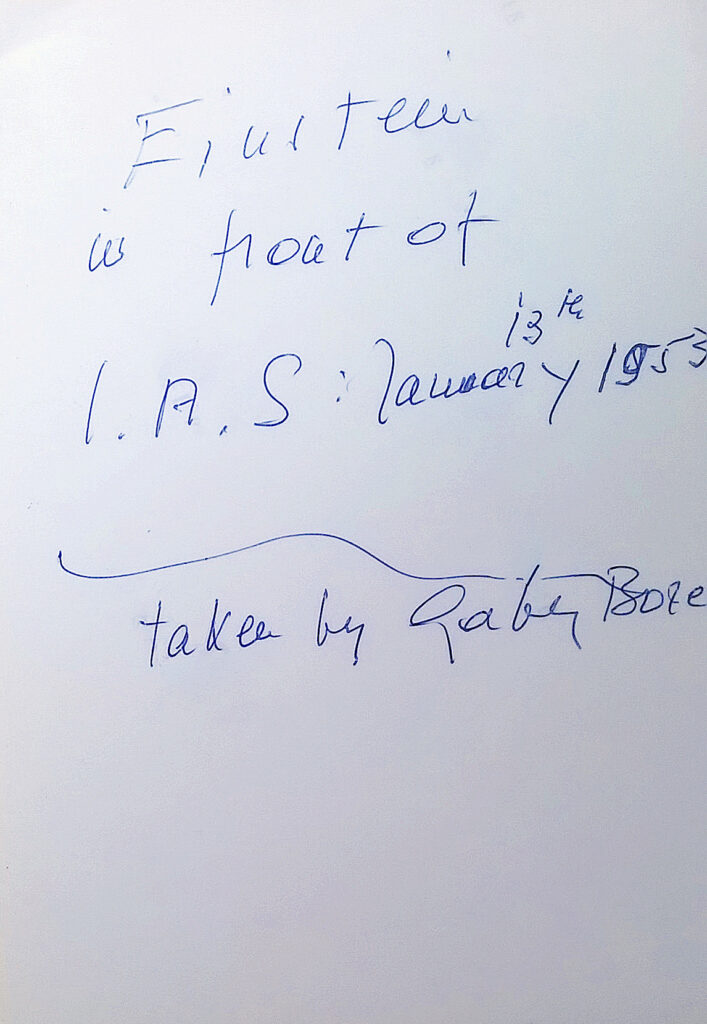

One of the architectural marvels that we visited was the great Thanjavur Brihadeeswara Temple, built in the Chola architectural style by Rajaraja I in 1010 CE. This ancient temple is a sight to behold with its towering gopuram and Linga, and with the huge seated image of Nandi in eternal attendance to the Lord. The four of us looked, admired, commented, and were hugely excited to share our thoughts on this journey of discovery. After stopping by smaller temples enroute, our South Indian tour culminated with a visit to the Airavatesvara Temple at Darasuram. This temple complex was built by Rajaraja II in the 12th century CE. Both the Brihadeeswara Temple and the Airavatesvara Temple are recognised as UNESCO World Heritage sites. The Airavatesvara temple is magnificent. The main temple incorporates an amazing chariot structure drawn by horses and elephants, where the wheels are visualized as circular discs, namely of the Sun and the Moon. The temple is a breathtaking sight filled with exquisite sculptural representations of life. On this trip, what I found special about Armand and Gaby was their sensitivity and respect for another culture. I noticed their genuine curiosity to understand the context of a temple visit, iconography representations, and Indian philosophy. I was personally moved. As fate would have it, when we finally arrived at the Darasuram temple, we were informed that it was flooded! Yes, flooded! The whole temple was inundated by incessant rains and in knee deep water! Apparently, this occurs frequently as the temple is at a lower level than the surrounding areas.

Luckily, that day there were no other brave tourists in sight, and so we had the temple entirely to ourselves. Nothing could deter the four of us and we decided to forge ahead. This meant that Armand and Gaby had to roll up their pants and my mother and I had to hold our sarees knee high. And then, dressed in this fashion, we walked, or should I say waded, into the temple complex. We were not prepared for what we saw! The entire temple looked like it was floating, almost as if it was on the move! The horses and elephants pulling the grand temple, swam in the water. The lower friezes of the temple came alive in the dazzling sunlight, their images lit by sharp rays reflected off the water. Everything was in motion, it was surreal. Unaware of the heat, our clothes wet, we waded through the glinting waters, circumambulating the temple in a clockwise direction, with each of us in turn excitedly pointing to others the sculptural details we observed in the friezes. Musicians played their instruments, dancers danced, and all of life etched in stone simply came alive. It was an unbelievable sight, and still remains an unforgettable experience. Finally, we ascended the stone stairs making our way to the main shrine and dry ground. Somewhat dishevelled but full of enthusiasm, we stood transfixed at the sculptural representation that greeted us on multiple pillars. And there, as if ordained, sitting in a cool dark corner we were fortunate to meet an exceptional guide. This was a blessing, as he was learned, passionate and immersed in the lore of the temple of Darasuram. He took us around, pillar by pillar, explaining intricate details, meanings, and the philosophy that echoed in what we saw. And this, sometimes, by the light of a single matchstick! We peered, observed, exclaimed. It was a befitting end to our temple tour. Energized and joyful, we knew we had shared an unforgettable experience. The trip was a gift of precious things—heritage, learning, and an enduring friendship.

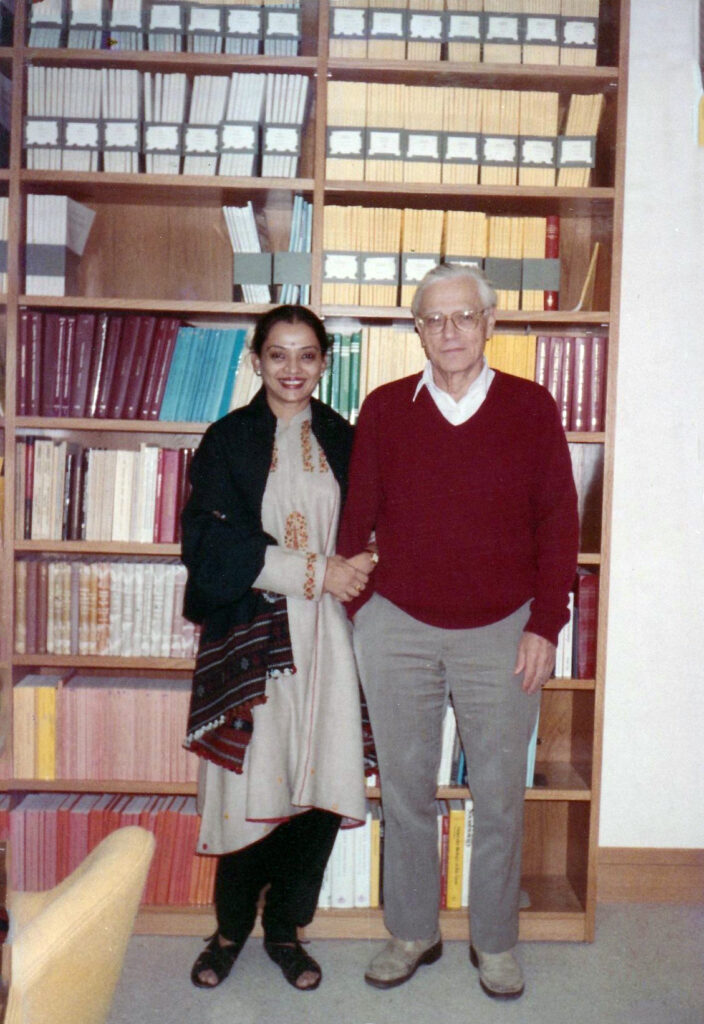

years, on one of my performance tours to the USA, my mother and I stayed with the Borels at Princeton. This was a unique opportunity to see Armand in the setting that had nurtured his deep passion for mathematics. It was moving to see the simplicity of their home, their life. Armand took us around the hallowed grounds of the IAS, personally pointing out things of interest. We took walks together, at times ate in the cafeteria, and listened to jazz music in the evenings over shared conversations. I remember that it was autumn. A season when trees are ablaze with the myriad colours of the Earth and leaves carpet the ground. And now, when I think of it, a season that metaphorically reminds me gently of the splendour and passing of life.

acknowledgements I would like to thank C.S. Aravinda and Sudhir Rao for inviting me to contribute to the issue of Bhāvanā celebrating the centenary year of one of the world’s outstanding mathematicians, Armand Borel.

Eclectic interests and the generosity of the Borels

– Shashank Subramanyam in conversation with C.S. Aravinda

The year 2023 was Armand Borel’s birth centenary, and is the context that brings us together in this conversation. In that light, I thought I’ll begin by telling you a little bit about Bhāvanā. It’s an outreach magazine, touching upon several varied aspects of mathematics. In the Indian tradition, as in certain other cultures, mathematical aspects are discernible in seemingly disparate pursuits like music, architecture, sculpture, poetry, and so on. Notably so, in addition to being a world renowned mathematician, Borel was seriously interested in various aspects of Indian culture as many who knew him have articulated. We, therefore, felt that carrying a tribute in his honour in Bhāvanā would be very appropriate – both to be celebrated and commemorated. We have heard that you knew him well for many years and that he appreciated your music. Can you please recount the circumstances under which you first met Armand Borel and his wife Gaby?

SS: Sure! You are right in saying that music and mathematics have always gone together. I’ve personally had great association with many mathematicians, and noticed that many mathematicians have demonstrated a strong interest in music.

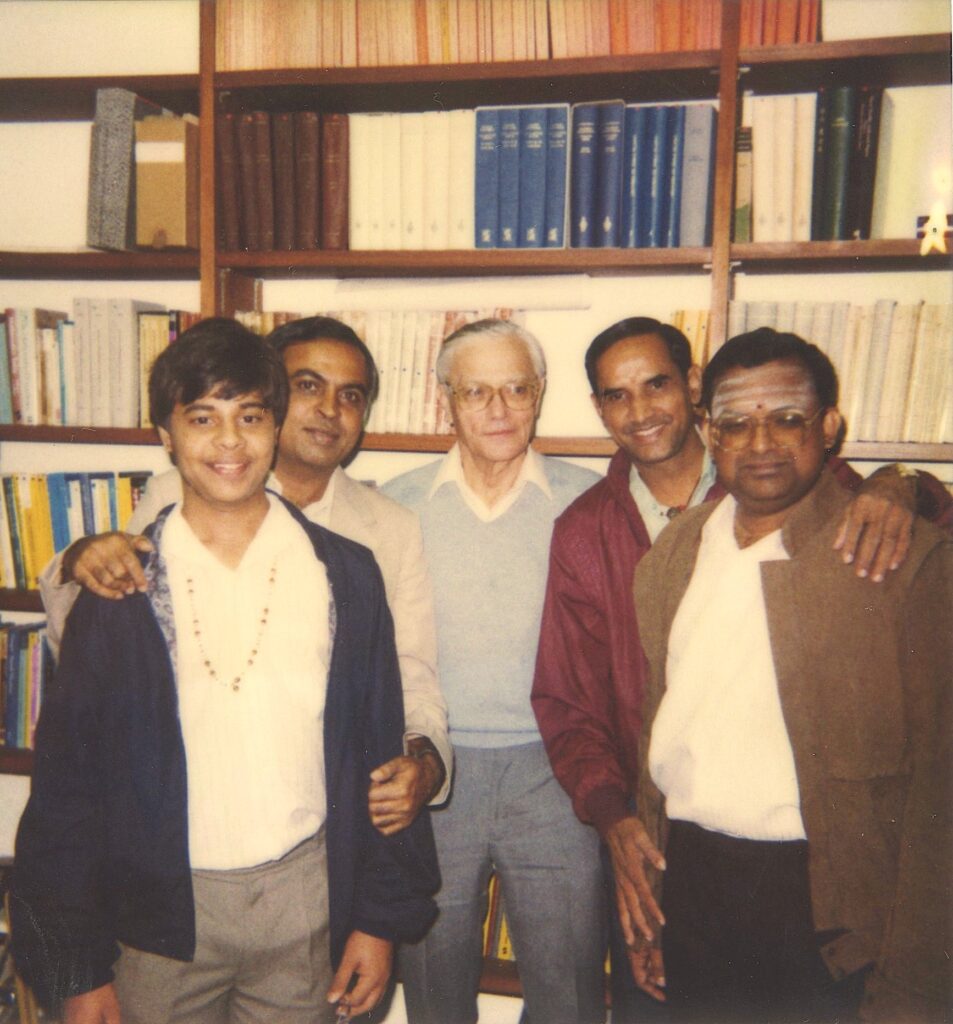

Coming to your question on how I met Armand Borel. There was a conference organized to celebrate the 60th birthday of Professor C.S. Seshadri by the Chennai Mathematical Institute, sometime in the year 1991. I was asked to perform as part of the conference celebrations, and the concert was held in the hotel Chola Sheraton in Chennai. Incidentally, Professor Borel too was attending the birthday conference. After the concert, he met with my father and talked about his great interest in music. In particular, he told my father that he was very impressed with my musical ability! Professor Borel further asked my father what he could personally do to help me and my art; and that is how our long and beautiful relationship started off. Closely followed by the 60th birthday conference at Chennai was a similar conference, this time held in TIFR Mumbai, and where it was much bigger in scale.

How old were you then?

SS: In 1991, I was 12 years old. At that point my father was himself exploring ways of taking my music to the US. It was in that context that Professor Borel said “Let me offer you a concert in the Institute’’, which incidentally is the famed Institute for Advanced Study (IAS). He quickly organized the promised concert in October of 1992, within just a year. During the course of that year, Professor Borel was here in Chennai as well and he would meet us often. He would invite us to some restaurant for dinner, and we too would invite them both—Borel and his wife Gaby—to our home. This is how our relationship flowered, primarily founded as it was on a shared love for music. Borel was a keen listener of music, and was somebody who paid a lot of attention to the artist, its historical aspects, and also the theoretical underpinnings of music. As our relations developed, we would speak not only a lot about music, but also on many other allied things. He was deeply interested and would inquire about how the traditions of music had developed in the Indian context. My father, more than my own self, used to have wide-ranging conversations with Professor Borel on religion, music, the science behind music, and such. Another thing that stuck me was how strongly Professor Borel was interested in finding out the many subtle intricacies of music, things that many would usually miss. My father would sit with him for hours discussing how different types of essentially mathematical and combinatorial ideas got translated to music, and how these musical combinations were presented by different musicians.

Another thing that I want to share here is his deep and eclectic choice when it came to music, and arts in general. When I visited Professor Borel at his home in IAS, Princeton, it struck me that he had in his immaculate and exhaustive personal collection, over a thousand LPs.4 And some of them were among the most beautiful and rare recordings ever possible. He even had some rare gems belonging to the genre of Indian music that we Indians ourselves possibly would never have access to; and all of this was a big surprise to me. I reckon this must have been because of his connection to many people around the world. He would often receive gifts of exquisite recordings from privately held concerts, in cassette tapes. Once he received them, he would diligently and carefully store them after writing a little piece of historical detail about the musician; and file them all away according to a personally designed index.

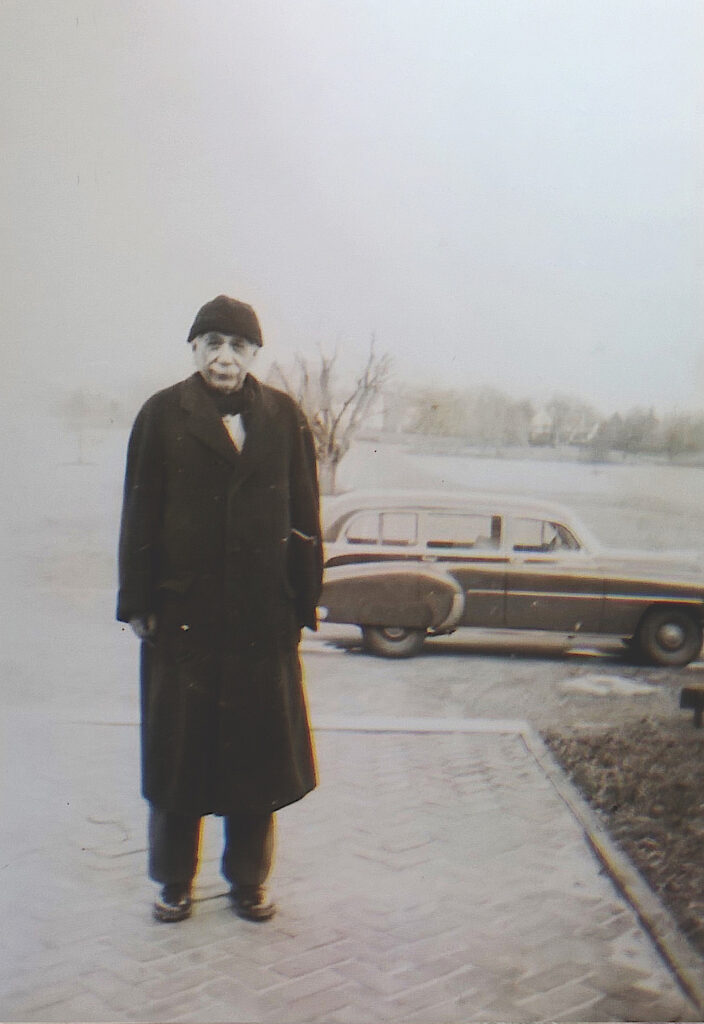

He would sit in rapt attention, and patiently listen to the musicians speak in detail about what they had just presented. He would before long dig out and discover a lot of things on both the music and the musician. He was temperamentally speaking, quite a serious person on one front, and quite jolly and jovial on the other. He was very beautifully complemented by his wife Gaby, who was a fun loving person, and also highly compassionate. She would often travel with Professor Borel with a camera, constantly clicking pictures. If you ever saw the Borels’ home at IAS Princeton, you would see that it was filled with pictures. I mean, literally thousands of pictures! Gaby would even have very diligently written notes behind every picture–-as to where it was taken, and also in what context the photo was taken. She would not just take pictures, but would make sure that it eventually reached the person in the picture. So she would typically make many copies, write beautiful accompanying letters and notes, before shipping them all to delighted recipients.

Gaby would have diligently written notes behind every picture–as to where it was taken, and the context.

|

|

|

| Photo of Einstein taken by Gaby Borel Dominique Borel | ||

Culturally speaking, their heart and soul were more European than American. They also had a beautiful house very close to Lausanne in Switzerland, which I visited. Gaby was one person who always paid a lot of attention to food, and the entire responsibility of actually running the Borel household. She was highly detail oriented, and very artistic. The Borels were also great friends of Malavika Sarukkai.

Yes indeed! In fact, Malavika Sarukkai has sent us her own fond reminiscences of the Borels, which are as fascinating as your own narration. Incidentally, was your trip to Princeton in October 1992 your very first visit abroad?

SS: No! It was not my first visit abroad, but it was my first visit to the US. I would also like to add here that in the year 2003, I was supposed to move to the US for an entire year, and unfortunately, Professor Borel had just then passed away. I sadly could not make it in time to meet him before he passed away, but what I want to say here gratefully is that his wife Gaby offered me accommodation for many months at their family home in IAS. Consequently, my colleague and I stayed at Professor Borel’s house for around seven to eight months, exploring America in the year 2003. Gaby was a great host, very generous, and deeply affectionate. She took great care of me, and all this was simply because Professor Borel had liked my music a lot. His daughters were very fond of me too, and they all agreed instantly to help me then – accommodating me and a friend for nearly seven to eight months at their parents’ home; which if you look at it now, was an act of extraordinary kindness and generosity. I knew nothing then about cooking or anything else, and that part continues to be so to this day. Gaby would take us every day to the cafeteria at IAS, where she would treat us very well; and when we came back home, she would check on us by bringing some chocolates or fries. I would also drive her around for some shopping here and there sometimes.

When Professor Borel passed away, it was the family’s wish that the ashes be brought and scattered around places that he had been to and greatly liked. One such place was the Darasuram Temple. Another was the Mahabalipuram temple and the beach nearby. I also played a tribute concert for him at his memorial organized by the Institute for Advanced Study. A lot of mathematicians from around the world had assembled there for the event. I remember that Professor Raghunathan from TIFR Mumbai was also there to give a talk on Professor Borel and his work. I played the concert in the new Concert Hall that was built by a generous donation from the then President of the World Bank, Mr James Wolfensohn. It is a very professional concert hall, seating about three to four hundred people, and nestled in a corner of IAS campus.

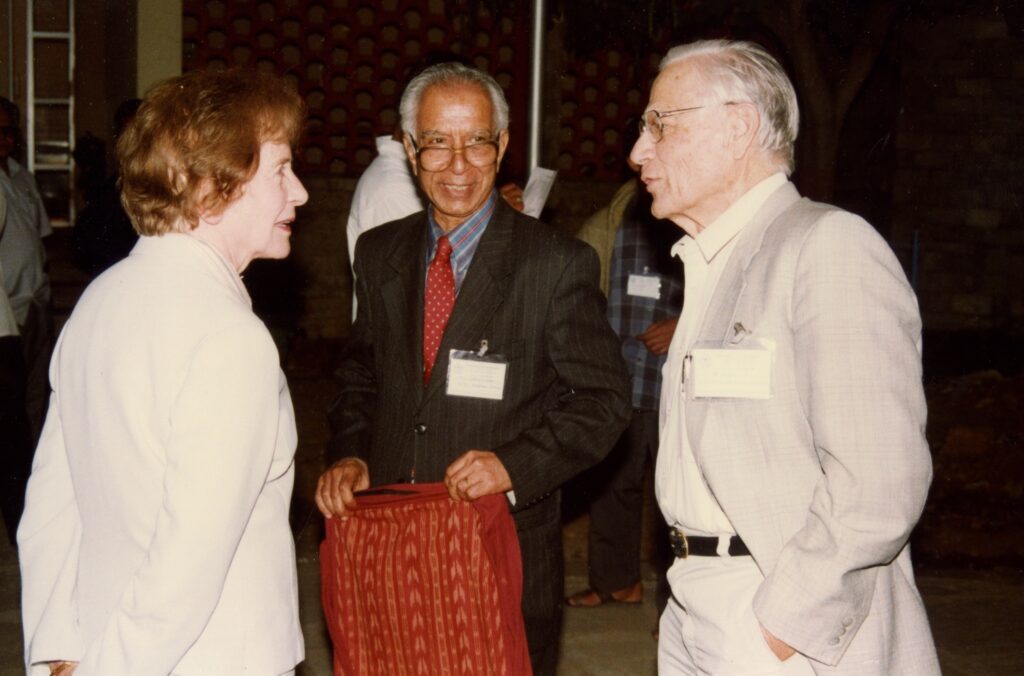

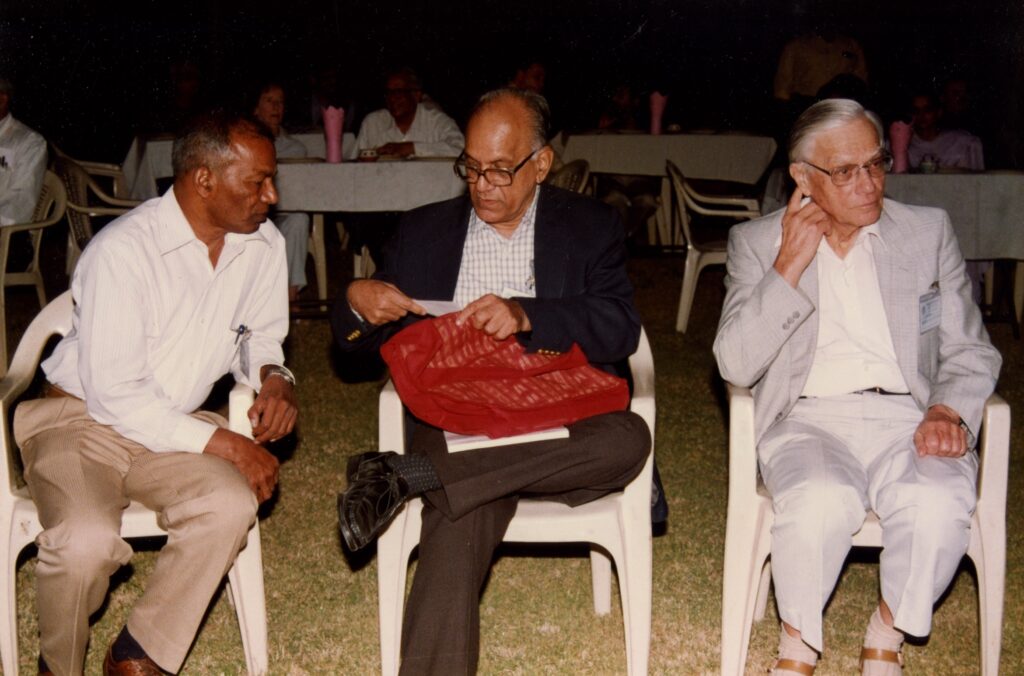

I first saw Borel when he visited TIFR Mumbai. I had heard that he was very interested in music, and in Bombay there are usually more Hindustani music concerts than Carnatic concerts. I had seen him once in attendance at one of Kumar Gandharva’s concerts held at The Nehru Centre in Worli accompanied by my friend Dinesh Thakur, way back in November 1990.

SS: Oh yes! He loved the Gundecha Brothers, and he loved the Dagar Brothers too. As I mentioned earlier, he also had such beautiful recordings that were very carefully preserved. Professor Borel had a very good sound setup from the 1960s or the `70s. He had some exquisite wooden speakers that he valued a lot, and he would take good care of everything in his possession very carefully. He was a very disciplined human being. I mean absolutely disciplined! All his conversations were so intellectual that I just can’t recall a moment when Professor Borel was really speaking something off topic. He was a wonderful human being with a stern external appearance; but inside was a heart of gold.

That’s what many of us have heard about him.

SS: He was quite upfront in his opinions too, and he never held back anything inside. He would just be so honest. In fact an accomplished mathematician who gave a talk in an event commemorating him had a very interesting anecdote to share. It seems Professor Borel met him once on some occasion, and no sooner had he introduced himself to Professor Borel, did the latter bluntly say that a certain part of a research article that this mathematician had recently come up with, was wrong. Needless to say, this candour had left him pretty disturbed and all the more because it had come directly from Professor Borel; and so he went back home to have another close look at his article, only to discover that what Professor Borel had said was indeed absolutely correct.

I think such a thing happened with the mathematician Nolan Wallach and, in fact, this incident is mentioned in Wallach’s obituary tribute to Borel.5 Do you recollect interacting with any other mathematicians during your long stay at IAS?

SS: I recall that Professor Raghunathan of TIFR Mumbai once came home for dinner at the Borels, when I was there. There was also an Ethiopian scholar who was quite close to both Gaby and Borel. I also recall meeting Professor Philip Griffiths. There were also other mathematicians from around the world such as Professor Shiota from Japan, Professor V Lakshmibai from Northeastern University, that I have met at other times. When I was in Chicago, I would also stay with Professors Madhav Nori, Pavaman Murthy and Ramesh Gangolli. Another mathematician from Chicago who regularly used to attend my concerts was the late Raghavan Narasimhan.

You have travelled abroad extensively, especially to the US, Europe and many other countries too. The Institute for Advanced Study is a very special and unique research institute in the sense that it doesn’t award PhD degrees, so you don’t expect to see too many people around. Did its ambience and temperament strike you as being different? Was there any impact on your artistic mind?

SS: I don’t think I can say anything deeply significant about this, although I quickly came to realize and understand that the place was unbelievably and justifiably special for people in the sciences. Almost every individual whom I had the opportunity to meet over the many lunches that I had in the cafeteria of IAS was remarkably accomplished in his or her own right. I have run into so many great people who were all residents on the campus, and one such person who was very interested in music and also a very accomplished mathematician was Manjul Bhargava. Manjul Bhargava has even visited me here in Chennai. He was one person I met in IAS who was very keen on music. In addition to being an accomplished tabla player himself, he was the person who invited Ustad Zakir Hussain for a residency program in Princeton. Manjul has also attended many of our concerts, especially that of Pandit Jasraj whom I was a disciple of. I used to play with Pandit Jasraj when he would perform in Bombay or Delhi. Manjul would show up at these concerts, and we would end up discussing a lot of music.

This is indeed a fascinating recollection of your varied interactions with Armand Borel and his family. What are your parting thoughts on the multifaceted person that Armand Borel was?

SS: I must mention this fact again at the risk of repetition. After his passing away, in accordance with the wishes of his family, his ashes were taken to the places that he really loved and respectfully scattered there. I personally took his ashes to Mahabalipuram honouring the family’s wishes. It was a deeply touching and emotional moment for all of us. Professor Borel was very fond of Hampi and Pattadakal, and would speak a lot about those places. He also visited Belur and Halebidu and loved the sculpture and the temple architecture there. He would make it a point to come to our house every single time he visited Chennai. Gaby complemented him beautifully, always jolly and exuberant. Professor Borel on the other hand was a serious scientist; but they were both absolutely wonderful people.

All in all, I am very grateful that I came in touch with Professor Borel who was extraordinarily kind, generous and helpful to me. I should also mention here that apart from Gaby and Professor Borel, their daughters, especially Dominique, did a lot for me. She being an artist and an actor herself made it easy for me to connect with her. We both had many things in common. She even came and stayed with us at our house in Chennai when Professor C.S. Seshadri of CMI had organized a function in honour of Professor Borel, after his passing away.

I remember that it must have been around 2005 because much of Borel’s mathematical collection was donated to the library of the Chennai Mathematical Institute. So, this is another way his mathematical legacy continues in India. I used to be a member of the faculty of the Chennai Mathematical Institute at that time. It was also the first time that I met Dominique Borel, and we became good friends.

Finally, we are at the end of a truly fascinating conversation. We thank you for sharing your cherished and fond memories of Armand Borel, and his family. I wish you the very best for the future.

SS: It was indeed my pleasure too. Thank you!\blacksquare

Footnotes

- It is an Indian word for orchestra; a group of instrumentalists. ↩

- See Enrico Bombieri’s obituary note on Borel in the Notices of the AMS, Vol 51, Number 5, May 2004. https://www.ams.org/notices/200405/200405FullIssue.pdf. ↩

- More accurately, it is named after the Tamil month of Maargazhi, or Margashirsha in Sanskrit, which overlaps with December. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madras_Music_Season. ↩

- LP is short for Long Playing. It a microgroove phonograph record designed to be played at 33¹/₃ revolutions per minute. ↩

- Nolan R. Wallach. “Armand Borel: A Reminiscence.” Asian J. Math. 8 (4) xxv – xxxii, December, 2004. ↩