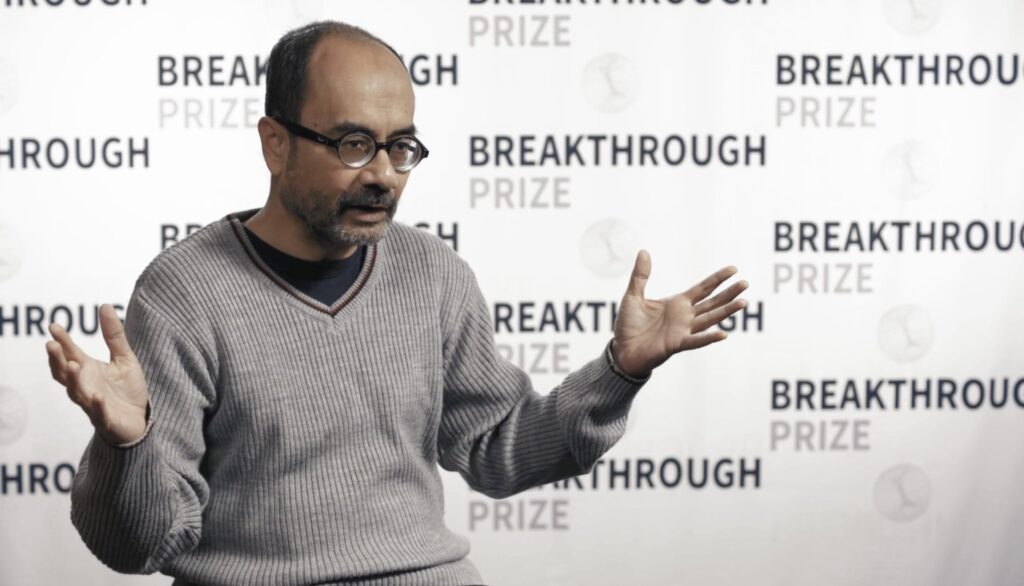

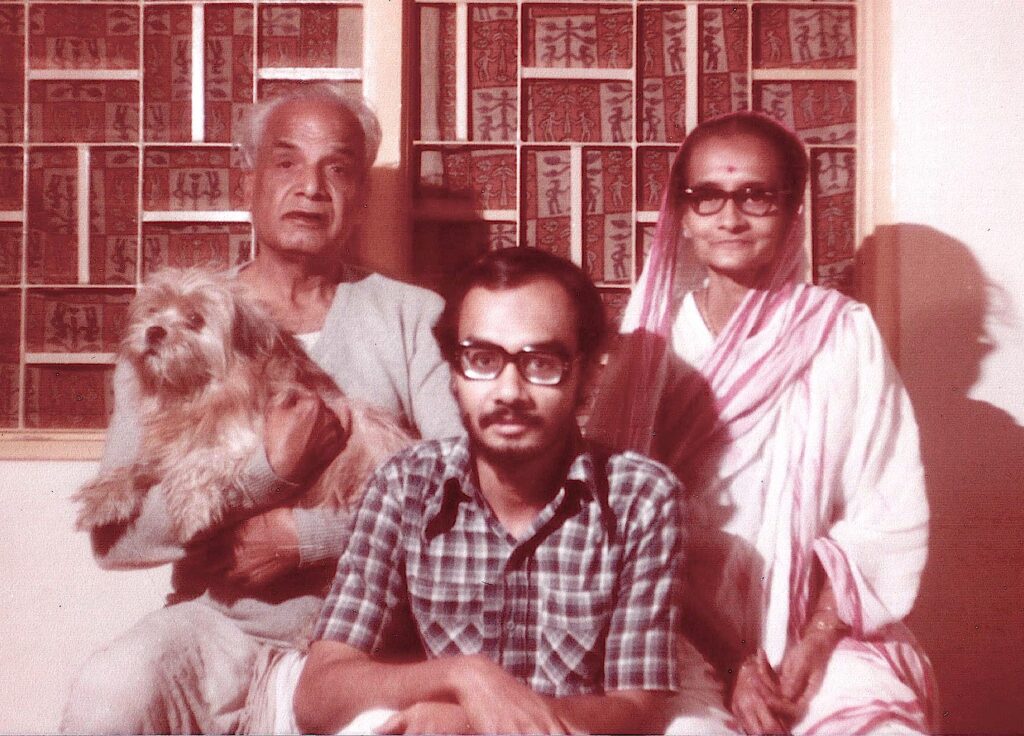

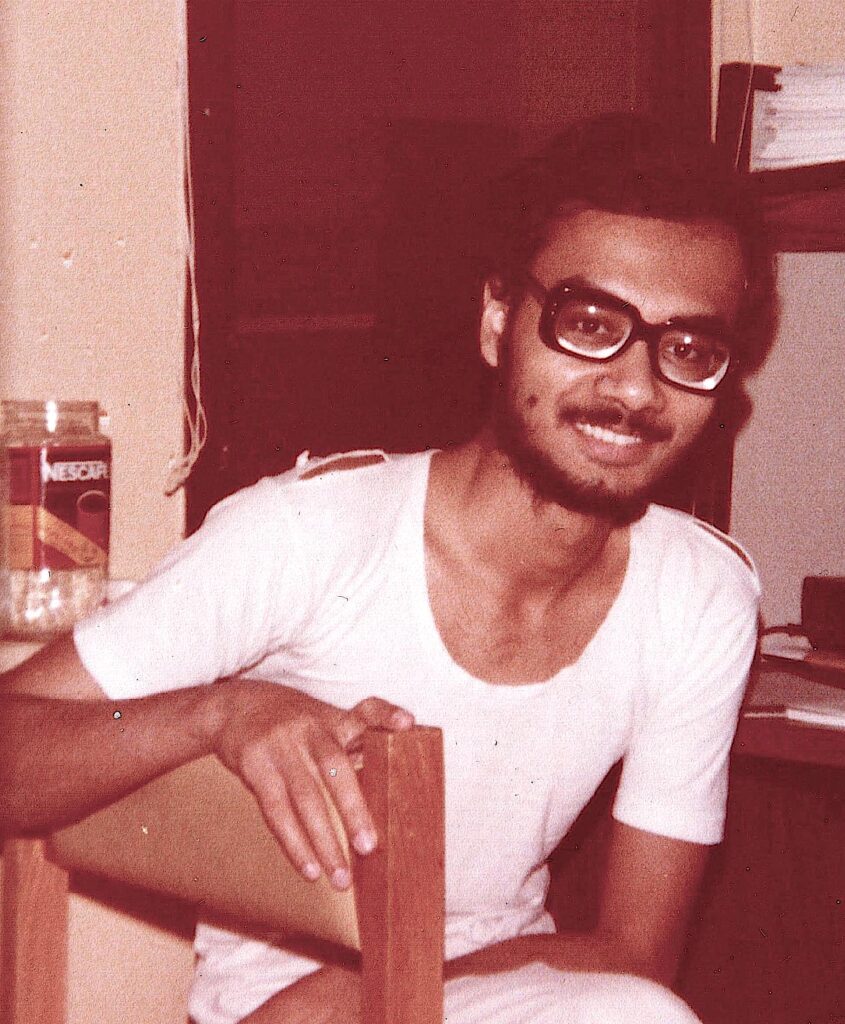

Born on 15th July, 1956, in erstwhile Calcutta, Ashoke Sen is among the most prominent and recognizable faces in physics in India today. Coming from the land that produced such greats as Satyendranath Bose and Meghnad Saha, and growing up in the rich cultural backdrop of Bengal, amidst all its upheavals and disturbed academic schedules, Ashoke has been through it all, in keeping with his calm and composure, as well as playful disposition entertaining himself in the free time afforded. A minimalist in his preference to go about his work, his natural choice gravitated towards a career in physics of the theoretical kind to the experimental, as he moved out to pursue his masters at IIT Kanpur, which also gradually directed him to his next move to the US where he finished his PhD. With the blossoming of his interest in string theory during his postdoc years that has remained the mainstay of his research, he went on to make several path-breaking contributions to the field, and is presently one of the most decorated physicists of our times, winning almost every award there is for physics, as well as distinguished national honours such as the Padma Bhushan.

In this relaxed conversation with team Bhāvanā, the genial physicist reflects on his academic journey thus far, peppered with insightful observations, even as he continues making impactful contributions to the field taking a pack of young and excited students along in his fold, and marching forth with elan.

It is a great pleasure to welcome you to this “in conversation’’ session with Bhāvanā. Could you first tell us about your parents and their life?

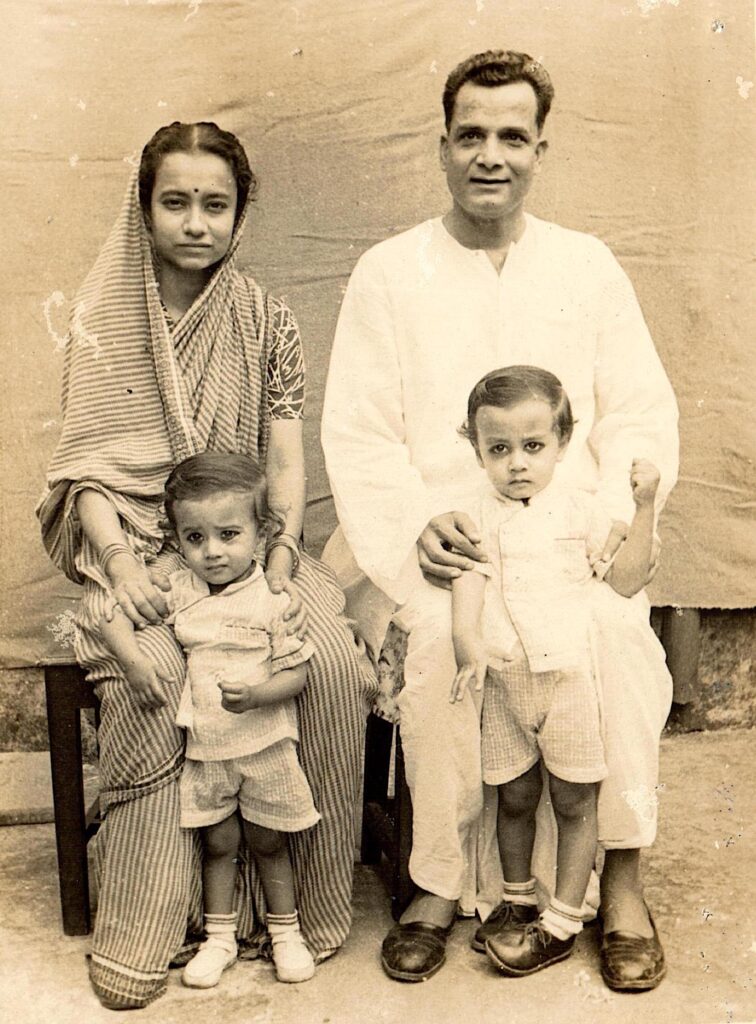

AS: My parents mostly grew up in Kolkata. My father, Anil Kumar Sen, was a physics teacher at Scottish Church College, and my mother, Gouri Sen, was working earlier but after marriage she didn’t continue.

My ancestors on my father’s side are from West Bengal, and on my mother’s side are from East Bengal [now Bangladesh]. My mother’s parents moved from East Bengal to Kolkata.

Would you know when and why did they move? Was it during the partition of Bengal reorganization?

AS: No, my mother’s parents moved much before the partition, mainly for reasons related to work.

Apart from your father, were there others in the family pursuing academic careers?

AS: Perhaps not exactly in academics as such. My uncle has two sons, both of whom studied engineering, if you call that academics. My maternal uncle was teaching botany in City College.

Do you have siblings?

AS: Yeah, a brother. He taught commerce in Serampore College. He is retired now. His name is Arup Kumar Sen. He is one and half years younger than me.

Was there anything in particular in your childhood and school days that steered you towards science and mathematics? Any recollections? Where did you study?

AS: Yeah, I studied in Kolkata at Sailendra Sircar Vidayalya, a school near our house. I liked the school.

There were ups and downs. Things were more or less smooth until the Naxalite period during my 10th and 11th standard. We had almost no classes as the school was closed most of the time, particularly in the last year of school.

So it lasted about a year?

AS: Well, the serious problem with schools lasted for about two to three years. The actual movement of course had started earlier.

So, you studied for class 10 and 11 exams yourself?

AS: We didn’t have separate exams in class 10 and 11 at the time. There was only one board exam for class 11 and for six months before that, you had to more or less study on your own.

See, in Kolkata, there were always disturbances, but not very serious ones. Maybe for five or six days in a year, there would be a strike and the school would be closed.

Apart from academics, were you interested in other things? Any other pursuit like sports?

AS: We used to go out to play, but nothing that particularly attracted me. I liked to play cricket or football.

I think football is much bigger in Bengal.

AS: Yeah, and importantly it also requires less equipment. You just need one ball!

Were science and mathematics always attractive to you?

AS: Yeah, in my school days I thought I will be a scientist, but I had no idea about science. That is probably because of the general culture in Bengal where science was considered a good thing to do. Otherwise, I was also interested in mathematics in school, but not in a very serious way.

In my school days I thought I will be a scientist, but I had no idea about science.

And you also read books outside of school?

AS: I didn’t study too much outside my curriculum. My older cousin, who was also staying in our house, was interested in reading popular science books. He would sometimes bring me some of them.

Was your father teaching physics an influence on you?

AS: Yeah, it was probably an influence from that side as well. But, as I said, physics was at that time the most popular subject in Kolkata. At that time the board exam was the main thing and central exams were not very popular. Five of the top ten students in the board exam were in my physics undergraduate class. In that sense, everybody wanted to do physics.

By physics, do you mean theoretical, experimental, or both?

AS: We did have experimental physics in school itself. In fact, the kind of experiments we did in school were more sophisticated than what I see people doing in schools now. I was very surprised that a student that I knew at a prominent school in Allahabad hadn’t worked with a spherometer or a micrometre screw gauge. The teacher would show them something and that was the lab! In our case, we actually had to do lab work between 6 and 7 in the morning as our physics teacher wasn’t a regular school teacher but a college teacher who would teach part-time. So we would go in the morning, do our lab work in serious labs with calorimeters, lenses and other hands-on devices. Not a sophisticated laboratory, but a standard one.

And was it a state government-run school1 or a private school?

AS: It was a government-aided school.2 It was not one of the fancy schools but a local school, I would say in between a municipality school3 and a government school. At that time, private schools were not very common. In the southern part of Kolkata, there used to be a famous school, but the most famous was the Hindu School which was a state government-run school.

So, ours was a mid-level school, not as bad as municipality schools but certainly not as close to the Hindu school. As far as I know, no one from our school ever stood, at least in my generation, plus or minus ten years, within top 10 in the board exam. In that sense, it was not a famous school.

Did you study in English or Bangla medium?

AS: I studied in Bangla medium up to high school, i.e, till class 11. I gave my board exam in Bengali.

Was the transition to English medium difficult or did it feel natural?

AS: Oh, it was not perfectly natural. I had to practise. For example, in the college environment, the tests were in English. So, I practised writing answers in English. But because it was only physics, it was not that difficult. We had terms for everything in Bengali and in college you had to learn what those terms meant in English. [laughs]

You did your undergraduate studies at Presidency College, Kolkata. How influential was that phase of life in determining your future career?

AS: It was probably partly influential, because as I said, many of my friends were already interested in physics. We had some very good teachers, like Amal Raychaudhuri who was a famous relativist. He was at Presidency College, and we also had many other good teachers. And, as I said, there were many other students who were interested in physics and many of them are still doing research in physics.

Amal Raychaudhuri of the Penrose–Hawking–Raychaudhuri equation?

AS: Yeah.

We have seen the book Classical Mechanics written by Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri.

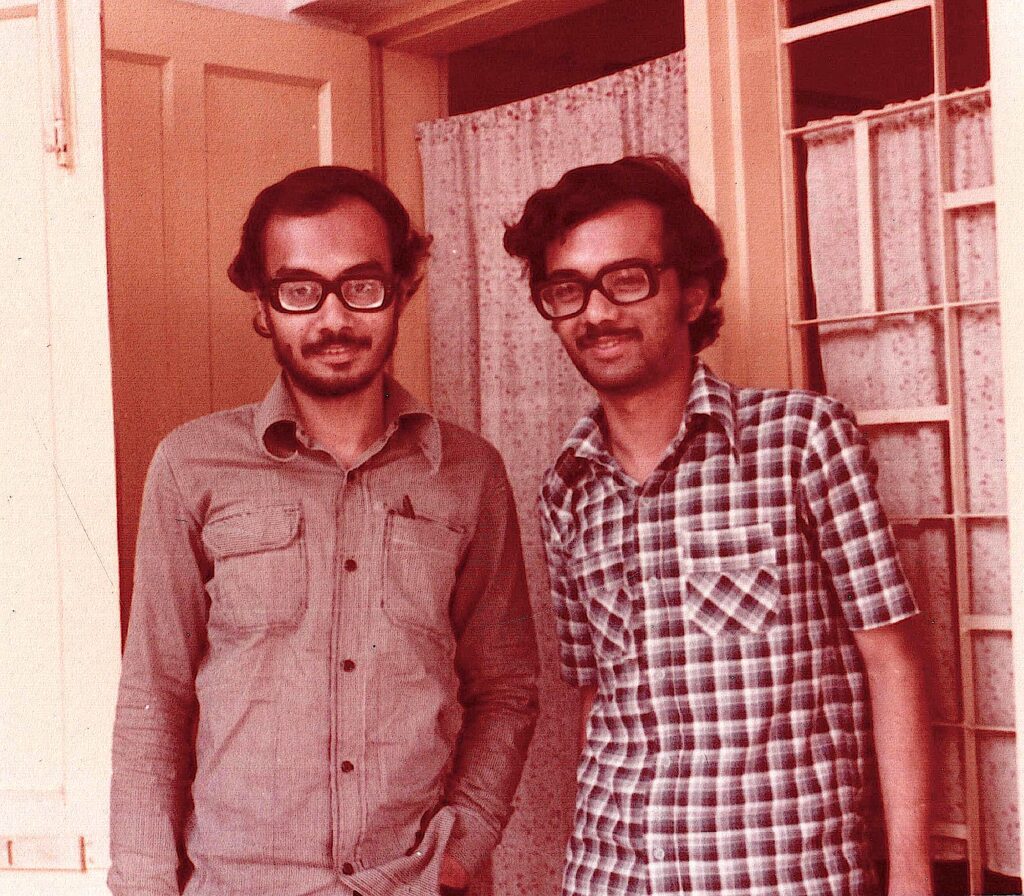

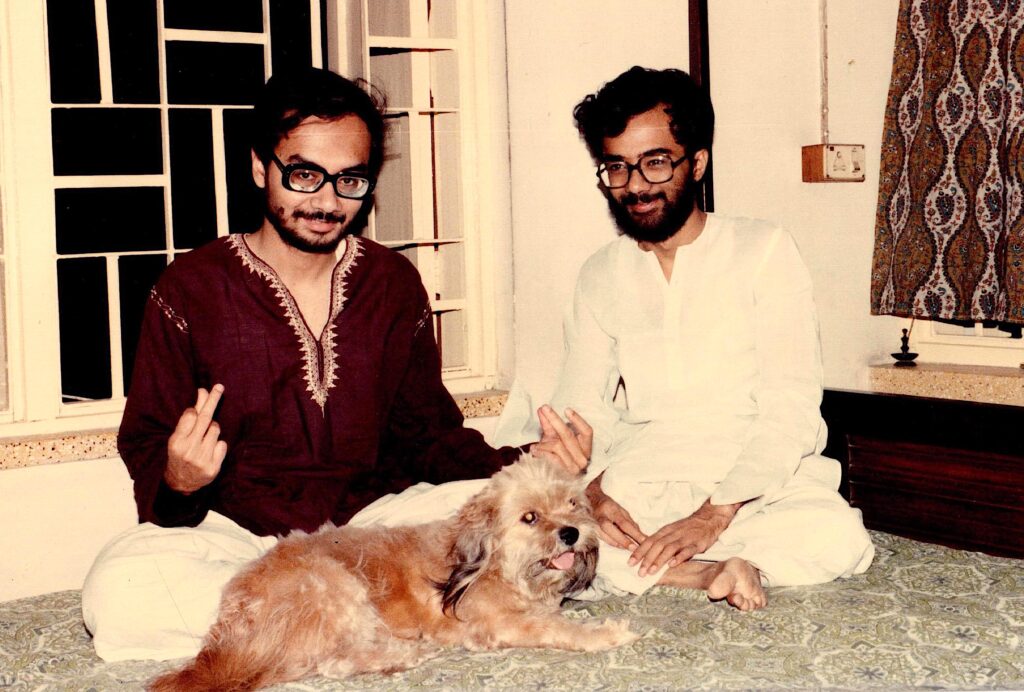

AS: For that book, the notes were taken by my classmates Sumit Das and Palash Pal. This was taught during MSc. I was not there at Kolkata for MSc as I went to IIT Kanpur. So the notes my BSc classmates took eventually came out as this book.

Was there anything unique to the syllabus at Presidency College compared to other colleges in Bengal?

AS: No, I don’t think so. Presidency College was part of Calcutta University and so it had the same syllabus. So I don’t think it was anything about the syllabus. It was just that this college used to have a name. Whoever wanted to do physics liked to go there. It is more that people concentrated there because of the reputation.

Can you elaborate a bit on your days at Presidency College and the atmosphere that existed at the time?

AS: We used to play cards a lot. [laughs]

Any game in particular?

AS: Bridge! Once I remember our principal saw us sitting right at the entrance of the college and playing cards, and he got so upset that he took all the cards away!

That didn’t stop you from playing cards, I suppose?

AS: Well, we had to get a new pack of cards. [laughs]

Do you still play cards?

AS: No, I found that I was spending all my time playing cards. So, I had to stop.

We had a lot of time though because we lost one year in BSc. Our exams didn’t take place as scheduled, and by the time the results were announced, it was already more than a year.

Why was that?

AS: It was because of the Naxalite problem. Exams were postponed. I mean the movement had died down by the time we went to college, but the effect was there. So that one year we spent playing cards. [laughs]

Starting from Presidency College, you have been in some top institutions. Do you think institutions still play a role in encouraging students to do science in India?

AS: Yeah, I think they do, in a sense. It is probably more due to the peer group. The teachers, of course, are important, but I think the institutions bring people together, people with similar minds and interests. I think that certainly helps a lot.

And you had such peers?

AS: Yeah, in college.

You mentioned Sumit and Palash, they were doing BSc in Presidency….

AS: They were my classmates. After we passed BSc they went to Calcutta University and Amal Raychaudhuri taught there as well. Presidency College had BSc and MSc, and the theoretical courses used to be common between Calcutta University and Presidency College because it was part of the same exam but taught in different colleges. So, Amal Raychaudhuri taught classical mechanics in the MSc course, but I was not there as I had gone to Kanpur.

What made you want to go to IIT Kanpur?

AS: We had heard about IIT Kanpur. We realized that if we stayed in Kolkata, we would have to lose one more year. My classmates who stayed back lost two years. So, IIT Kanpur was one of the options. We knew some seniors who had gone there. We just went for an interview there—four of us from Presidency—and got selected. But not all of us joined. Eventually only two of us, Bidyut Bhattacharya and I, went there.

Is he still in physics?

AS: He eventually moved to industry.

If you were doing a BSc in Presidency in physics, was it assumed that you would go on to do an MSc, or did people switch careers?

AS: I think it was assumed that you would go on to do an MSc. A few people moved out, but most people did MSc. And, as I said, in my batch almost everyone went on to do MSc. Even Bidyut moved to industry only after obtaining his PhD in Buffalo.

So, during your school and college, was there anybody who was inspirational?

AS: At school, science teachers were coming only for an hour to teach us and were not always part of the school. In college, we had some good teachers. Amal Raychaudhuri is certainly one of them, and Shyamal Sengupta is another. There were also other good teachers.

Who were the physicists who were household names in Bengal at that time?

AS: Well, S.N. Bose, Meghnad Saha and Jagadish Chandra Bose. If you asked anyone passing on the road, they would know these names.

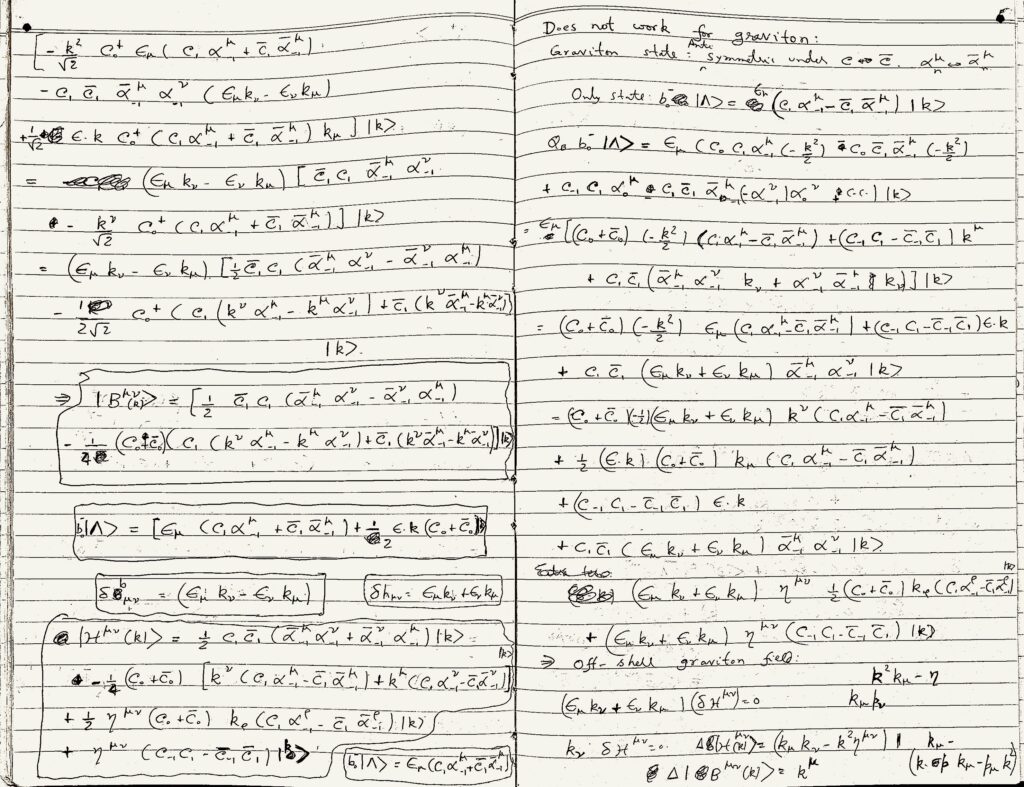

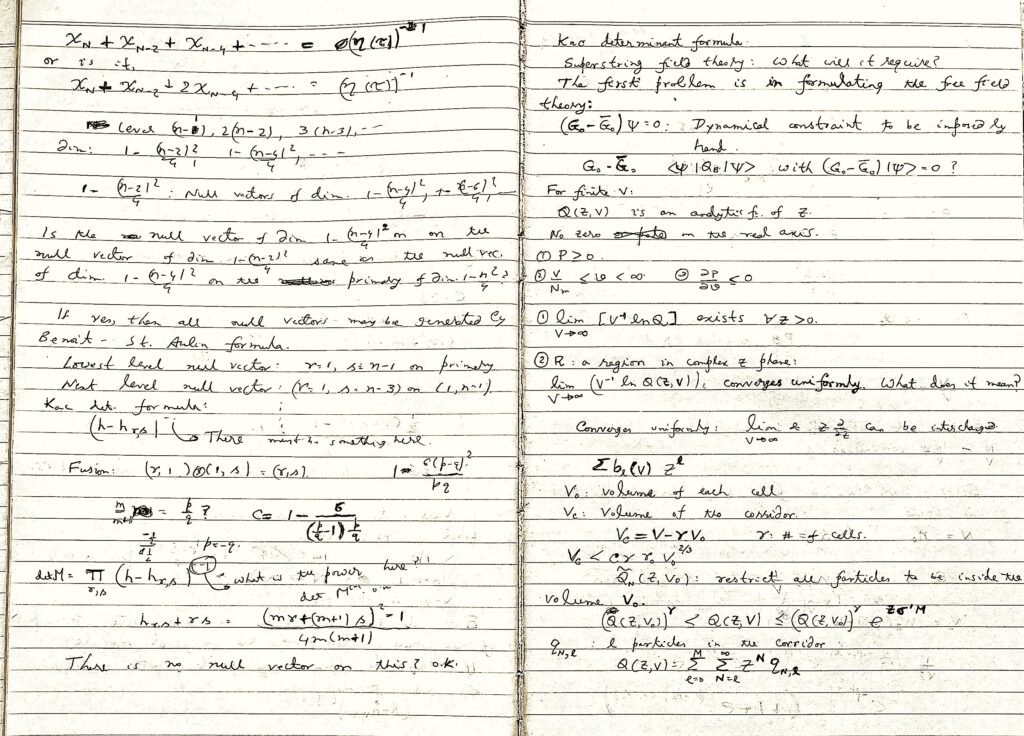

I recall that you keep a long hardbound notebook to take notes of the lectures that you attend. You mentioned that it was an early habit of yours that you started during your college days. I also remember that you mentioned you have a whole collection of all those notebooks.

AS: Well, those notebooks were different. Back then, I used them to take notes. But the actual habit of working on notebooks started when I was a postdoc. This was around 1983 or 1984.

Do you refer to those notes any time?

AS: Very rarely. If there is some calculation in some paper I find, and I am not recalling how I got there, then I have to go back to those notebooks and check. And these notebooks are dated. It is hard, but it is not completely impossible to find.

That is because you remember these calculations?

AS: No, I don’t remember. I don’t go back to old calculations very often directly. Only when somebody asks something, then I have to go back to my old calculations, and then I have to try to remember.

Does that habit still stay with you?

AS: Yeah, I still use notebooks. These days of course people use gadgets. So far, I have stuck to notebooks.

How were your two years at IIT Kanpur? Was there a similar craze for getting into IITs in your time?

AS: Not really. I wouldn’t say so. Certainly not in physics at least. It was a good place, but I don’t think it was as competitive as it is now. Even across India, I don’t think engineering at that time was that competitive.

Was your interest in physics fortified there?

AS: Yeah, certainly. I started reading more advanced material there. Like general relativity, for example; we didn’t have a course but I started reading about it. We also had some advanced courses like quantum field theory.

Which book on general relativity? Any particular book?

AS: I think I was reading Steven Weinberg’s Gravitation and Cosmology.

You also perhaps read Principles of Quantum Mechanics by Paul Dirac.

AS: Yeah, those were part of our course. Quantum mechanics was very much part of the course, but not general relativity.

Was there a thesis component to the MSc?

AS: The thesis was experimental work. I mean, I had to do an experimental project during the last year as part of the thesis.

So, what was that experiment about?

AS: It was about disordered materials. You had to measure properties of disordered materials at low temperature. There was no possibility of a theoretical project at that time and much of my time was spent in the workshop to get the apparatus ready. [laughs]

Did you enjoy that?

AS: Yeah, I enjoyed it!

Did you ever seriously consider working in experimental physics?

AS: No, I mean somehow, I felt that you have to depend on too many people if you want to do experiments. As I said, most of the time I spent in the workshop. It’s not completely up to you. You have to really depend on the workshop people and various other resources. So, I felt that theory is much easier.

You need some level of organization for these things to be ready.

AS: Yeah, and you have to be able to manage people.

What were the other books that were used? You said, relativity was outside the curriculum. I remember, you had mentioned that you were taught Classical Mechanics by Herbert Goldstein.

AS: Yeah, Goldstein’s Classical Mechanics and Principles of Quantum Mechanics by Leonard Schiff. For electrodynamics, I think, we used John D. Jackson to some extent because we had a course on advanced electrodynamics.

Did you have some mathematical topics to study?

AS: Yeah, mathematical physics. Basically complex analysis, partial differential equations, special functions….

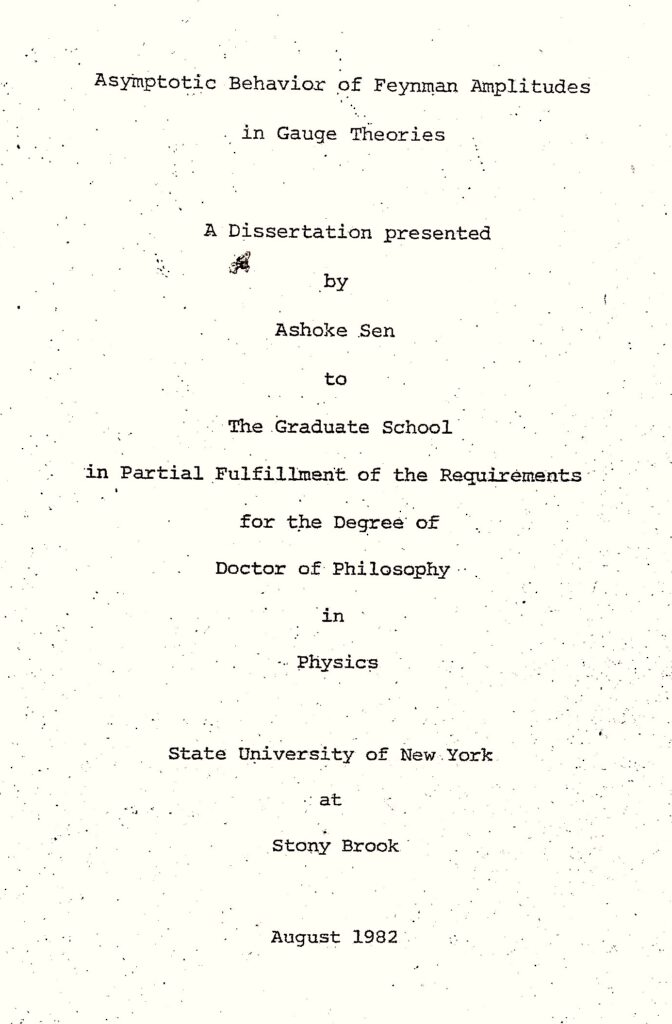

From IIT Kanpur you went to Stony Brook for a PhD. Was it an option that was available to you, or you applied to several places and then chose Stony Brook?

AS: No, I applied to only two places because I had to choose those places which didn’t require an application fee. Stony Brook was one of them. And Princeton wanted an application fee but you could apply without the fee, and pay later on. So, I applied to both of these places. I got into Stony Brook, and I joined there.

Did your interest in string theory start in Stony Brook?

AS: No, string theory came later. In Stony Brook, I worked on particle physics. I was interested in more fundamental aspects of physics, which included general relativity and particle physics. I started working on string theory only during my postdoc years in Fermilab.

Who was your advisor in Stony Brook, and how did you choose your advisor?

AS: I didn’t have much idea how to choose an advisor. George Sterman was my advisor. He was a younger person and in fact, he joined a year after I joined. When he came, there were four students in a line at his office, each wanting to be his student. He took all four of us. [laughs] In fact, Sunil Mukhi also joined.

Sunil Mukhi and you were contemporaries?

AS: We were contemporaries in the sense that we were born in the same year. But Sunil went right after his BSc, and was in Stony Brook two years before I went.

Did you also have to do Masters’ level course work at Stony Brook?

AS: Stony Brook had some graduate courses but we didn’t have too much of a requirement. The number of courses we really had to do, I think, was basically two courses outside our thesis. There was no other course requirement. But you had to pass a comprehensive exam which could be passed either at the PhD level, or at the master’s level. If you passed the comprehensive, you automatically got a Masters. And it was mainly people who wanted to leave who took their Masters and left. You had to pass it within two years after joining.

Were there some noticeable differences in teaching styles between Stony Brook, IIT Kanpur, and Presidency College?

AS: Well, at Presidency College we didn’t have any homework. While the other two had homework. At Presidency College, we only had to write the final exam, and that was it. There used to be exams in the college every year, but those were not very serious in the sense that those were not counted for anything. It was the final exam which counted. The other two had a semester system.

Application fee was one consideration when you applied to Stony Brook. But did you consider any people in that department that you thought that you would work with?

AS: Not really. I didn’t even know who was there. I had a classmate who joined IIT Kanpur for MSc with me. But he left after one year and went to Stony Brook. So, we heard about that place from him. Otherwise, I really didn’t know very much about that place. Later on, I found that it was a big place for supergravity.

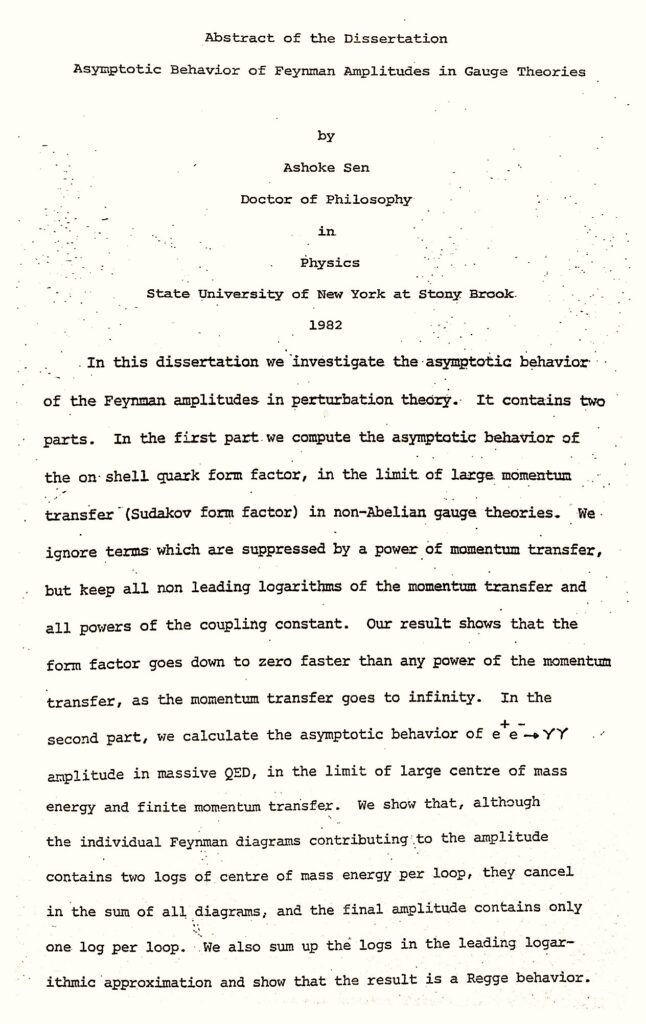

What was your thesis about?

AS: It was basically studying the high energy behaviour of scattering amplitudes. Normally, you study these scattering amplitudes using perturbation theory. There’s a coupling constant and you write it as an expansion in a coupling constant. My thesis work was in some sense trying to re-sum that series and write it in a compact form that makes it easier to study the result at high energy. When you do the perturbation expansion, you find that each term grows but the sum decays. It’s like an expansion of e^{-2x} for example, where the powers grow but it eventually decays.

|

|

So that was the mathematical content in your thesis?

AS: Yeah, it was mathematical, but I didn’t have to use any high-powered mathematics for this. It was more of analyzing integrals, where we had to look at the integrals and try to extract how it behaves for large energy and then had to re-sum that whole series.

For how many years were you in Stony Brook before you went to Fermilab and then to Stanford?

AS: I was there for four years. Then I was at Fermilab from 1982 to 1985 and then at SLAC (Stanford Linear Accelerator Center) from 1985 to 1988.

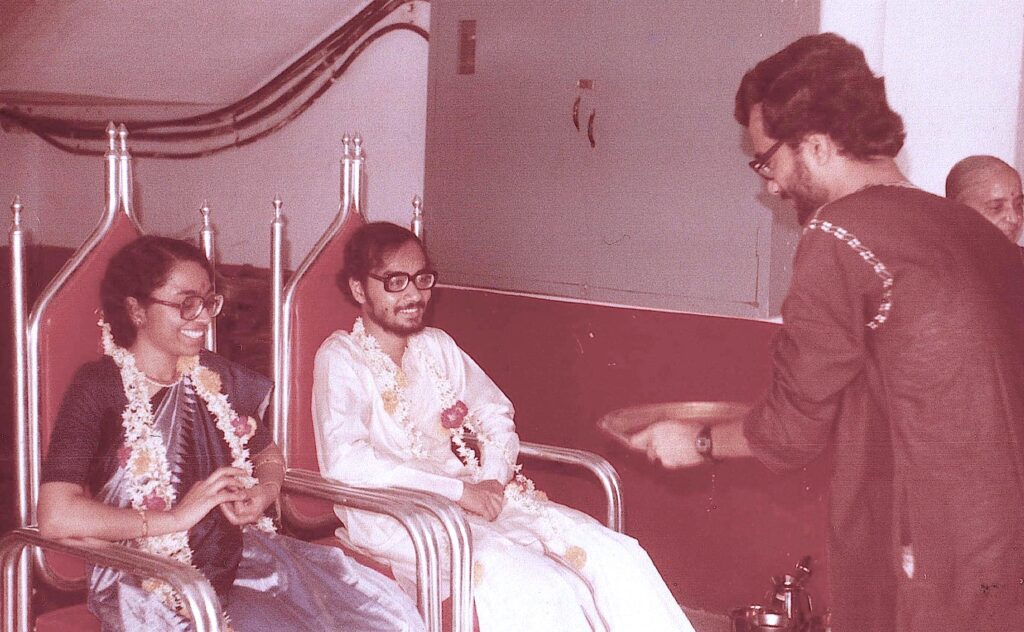

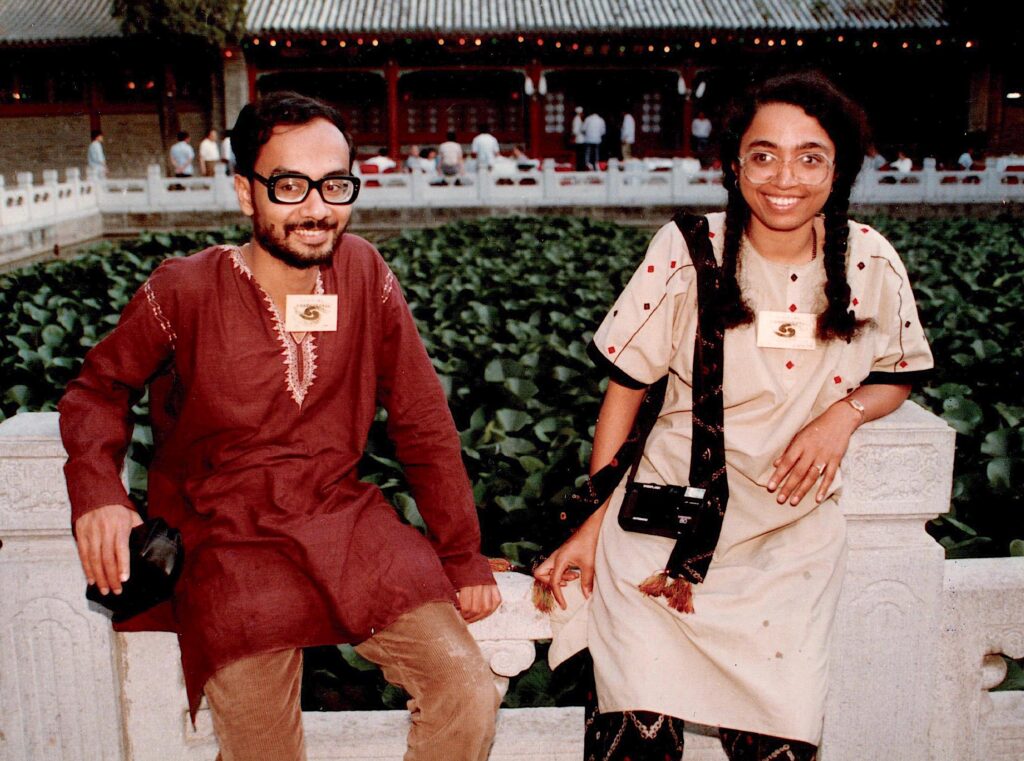

I remember you were visiting TIFR from Stanford when I first saw you at Sunil Mukhi’s apartment. It was at Stony Brook that you met your future wife, Sumathi Rao, I believe.

AS: Yeah, she was one year junior to me there. She too was in Stony Brook for her PhD.

You came back to India before Sumathi, I believe, and Sunil had returned and joined TIFR. It seems like quite a big contingent from Stony Brook—your peers, and before you, Rohini Godbole—came back. Was there any kind of a conscious discussion or it just happened?

AS: Actually, Sumathi came back about 6 months before me. To answer your question, I don’t think it was a conscious discussion but probably because one person came back and said good things, you feel it’s good and you also come back.

Definitely it is quite interesting that all of you came back and joined different institutions in India. Did it feel like a big change coming back to India after nearly ten years abroad?

AS: During that time it didn’t feel like a big change, though retrospectively maybe it was. The internet certainly made a very large difference. After I came back, for a while, it was hard to communicate with other physicists. Letters used to take a long time and you would not get papers on time as there would be a delay in their arrival by sea mail. But the internet came within a few years of my return to India.

Did you find any difference in the work culture between the US and India? Did you have to take some time to adjust yourself?

AS: Not really, I think the TIFR work culture was quite good. So, this didn’t require any adjustment.

When did your string theory phase start? Was it at Fermilab? String theory was a big thing then I suppose. Is that how you got into it?

AS: It started in the middle of my stay at Fermilab.

From various conferences, it did seem that to understand particle physics you have to understand gravity. And then strings were one of the natural candidates for incorporating gravity.

That’s how I started studying string theory, and then in the middle of 1984 there was a paper by Michael Green and John Schwarz which basically established that string theory can give a consistent description of gravity as well as other forces. I had tried to get in before by reading a review article by John Schwarz, which was written earlier. But, certainly after this paper came, it became clear that that’s the way to go. Before that, it was clear I was interested but I wasn’t sure if I wanted to work on that.

When you came back to India, there were people already working on string theory in India.

AS: Yeah, string theory had also spread in India. Sunil Mukhi, Spenta Wadia and Sumit Das were working on it.

Sumit Das was not in Stony Brook, right?

AS: No, but he was at Presidency College. And he was in Fermilab, and we were there together for two years.

After coming back you have, of course, mentored a number of PhD students and postdocs in India. Possibly all of them worked on one or the other aspect of string theory. What are the other topics other than string theory that have held your interest?

AS: I think everything that I have worked on has some relation to string theory. There are also some other subjects but again those that are related to string theory.

And your wife, Sumathi, works in a different area?

AS: Yeah, she used to actually also work on particle physics earlier. But then after she came back to India, she switched to condensed matter physics, basically, applying quantum field theory tools to condensed matter physics.

How different are the students now, compared to your times? Has the internet changed anything about the teaching and learning process?

AS: Intrinsically I don’t think there is really that much difference. Maybe, on average, the students now use computers more than earlier.

I remember that when you came to TIFR, you liked to work at night. I think you had a print-out of one of your articles printed out in a dot-matrix printer.

AS: Yeah, in fact, I had gotten a personal computer (PC) in a big box from the US. If you think of it now, it used to run really slow. But we could print in two different resolutions. The copies you sent to the journal were printed in high resolution. I remember, once, I think, I was collaborating with Sameer Mathur and Sunil Mukhi. On one paper we spent the whole night working. When Sunil left in the night, Sameer and I had started printing the paper and it was still printing when he came back in the morning. [laughs]

How long was that paper?

AS: That was about sixty pages. Each page used to take about ten minutes, and once in a while, something would go wrong in the middle.

Even for typesetting, I think TeX came perhaps later? Or did you use ChiWriter?

AS: Yes, I used ChiWriter once after coming back to India because it was fast and TeX was taking a long time. But TeX was more versatile and I knew it when I was in SLAC. I tried ChiWriter after spending a whole night printing to see if it improves things [laughs]. So I wrote one paper in ChiWriter. But then I switched back to TeX.

Do you think the digital mode of teaching/learning which we had to shift to during the pandemic years was effective? Especially given the huge skill gaps that we see at the school level. Does the physical environment play a big role in learning and teaching?

AS: Yeah, I think it [the physical environment] certainly plays a big role. Zoom was probably the best thing to do during the pandemic. It certainly made things easier. But if we have to compare Zoom with classroom teaching, I feel classroom teaching is certainly much better. But the hybrid system—teaching in a classroom with some people online—is worse than a Zoom-only class, because in a full Zoom class, at least the lecturer can be seen more easily and you can see who is talking.

You said that during your BSc, your classes were affected by the Naxalite movement. Suppose some of this technology was there, maybe it wouldn’t have affected your studies?

AS: Yeah, possible. Maybe, if this technology was there, we would have all had Zoom classes.

But you definitely think that classroom teaching is the ideal atmosphere for both teaching and learning.

AS: Yeah, because you can at least see the students’ faces. Otherwise, it is hard to gauge.

Even the academic conferences, many of them had gone to Zoom, and that seemed to have presented other logistical challenges like time zone differences.

AS: That is true, but I find that Zoom is better for big academic conferences, where 500 people attend, than in-person. If 500 people are sitting, and you’re at the back of a hall, if you have to ask a question you have to jump up and down. Whereas in Zoom it is much easier. But, if it is a small workshop—like 30 to 50 people—then it is much better in person because then you can really interact.

Do you still get motivated students in good numbers in research? Do you think that the new `Choice Based Credit System’ (CBCS) at the UG level in our country is helping in any way, research-wise and concept-wise?

AS: I think it is too early to say. It is a recent system. I have not really had students coming from that system. But we do get motivated students.

Do you see any kind of difference in students from earlier years?

AS: Maybe there is a difference between HRI (Harish-Chandra Research Institute) and TIFR. At TIFR most of the students used to come from urban backgrounds, whereas at HRI, we get students mostly from rural backgrounds. But this is likely due to a difference in the locations of the two institutes.

Did you have to alter your teaching method between both places?

AS: No, in the sense that while their English may not be as good, their physics is as good as that of any student from an urban background.

Was there any other difference in approaches to problem-solving at the entrance interviews? I ask because for places like TIFR, when I had to prepare for interviews, there were some standard questions that people know to expect. Students outside an urban background may not have known these things.

AS: I wouldn’t say there was a visible difference between the two. I think the way of doing physics is more or less the same for the urban or rural background people. Perhaps you are thinking of people who go to these JEE [Joint Entrance Examination] camps for a lot of coaching. For TIFR interviews, it is not that they have gone through a lot of coaching. I mean, nobody goes for coaching for a PhD interview, right? Nowadays, maybe they do but in those days people didn’t go to coaching institutes.

Not so much in coaching, but in their own preparation, in the sense of knowing from seniors what kind of questions were asked.

AS: Yeah, at least I didn’t find any visible difference.

But, actually coming back to this rural-urban difference, you mentioned that you studied in Bengali and a lot of scientific terms were in Bengali. Do you think that had an impact on rural students getting better access to science education in Bengal?

AS: It is possible, but I have a feeling that now they also probably study in English. They study in English only in a vague sense that they go to an English medium school. Like, we went to Presidency College which was an English medium college, but many of our teachers explained ideas in Bengali, and only the writing was in English. So in that sense, I think that now many of the students, even from rural backgrounds, probably write their answers in English in the exams. Their spoken English or grammar may not be good enough though.

But in terms of thinking in your own language, does it make a difference?

AS: It could make a difference! On the other hand, from the beginning, if you are used to speaking in English, if you come from a genuine English medium school where from age three you are taught to speak in English, then maybe it doesn’t make that much difference because English is effectively, like your mother tongue.

I believe you spent some time at NISER Bhubaneswar after the long stint in HRI, and before coming to ICTS. How did you find the students who came to study there?

AS: I only visited NISER for a few days, but did not spend long periods there.

When you are studying subjects like physics and mathematics in one language, and then the language changes, it can be a barrier to learning them.

AS: True, but many of the students who study in English medium schools now, they study English from age three. So, their language is English. They don’t have that barrier. The barrier comes only when you have learnt in one language when you are very young, and then you learn a new language and shift your scientific thoughts in that language. That can certainly create a barrier.

For me, shifting over to English took some effort as I had to practise. I had always learnt in Bengali. In that sense, I had a barrier because I didn’t know any other way!

If somebody is not comfortable in English, let us say, do you try to explain in Bengali?

AS: Yeah, I would certainly try to explain in Bengali.

Among your colleagues who speak Bengali, do you discuss physics in English, or do you also use Bengali?

AS: Mostly in English, I would say. Sometimes it gets mixed. If there are only Bengalis around and if I am talking about other things in Bengali, and physics appears in the middle, that also becomes Bengali.

If one wants to learn science topics in local languages like Bengali, is it still possible?

AS: Yeah, I think it is still possible. There are books that exist—maybe they are not the best books—but there are books in Bengali that you could read.

Since you have seen both, was it easier to absorb concepts in Bengali?

AS: See, I have absorbed concepts in Bengali since I was young. I mean, that is the only language I knew. So, it is hard to compare. If I had grown up from age three with English, maybe it would be equally easy.

By now, I have switched to English. I don’t necessarily think in Bengali anymore. I think the main change took place at IIT Kanpur. Because in college, as I said, we had to write our answers in English even though teaching was mostly in Bengali and we talked to our teachers in Bengali. In Kanpur, I had to really switch, because even to communicate with your friends you had to speak in English.

So that was a good transition period before you went to the US.

AS: Yeah, exactly.

In a similar spirit, scientists in research institutes—especially physicists and mathematicians—live in ivory towers, often disconnected from university education and ground realities. Knowledge that is created rarely percolates to the masses. How do you feel about that?

AS: Yeah, I think, it is certainly a problem. Maybe there are two things required to be done. First, you have to start an undergraduate program in the research institutes, and at the same time try to make the universities better. So, it has to be done gradually and cannot be a sudden change.

But of course, this kind of disparity you see is not new. It has been there for quite some time.

AS: Yeah, and you cannot remove it in one go. You have to also understand that this is a problem you have to gradually remove.

The IISERs [Indian Institute of Science Education and Research], for example, are much better than the standard universities. How to make the standard universities like what is seen in IISER is a difficult task, because there are already people there and the infrastructure is often poor. We have to make sure that the infrastructure is good and that the people who are hired are active researchers as well.

One thought that comes to my mind is that a way in which you came across the names of scientists and their institutes or universities was through the textbooks they wrote. If researchers wrote textbooks suited to Indian conditions, readers would come to know about them and want to meet the authors. I don’t know if there are any such efforts to write books but perhaps that is one way to improve the syllabus.

AS: At an individual level, people have written books. But at an institutional level, there has not been any concerted effort. It could make a difference. On the other hand, you can say, we already have textbooks, though not written by Indian authors. If you want to write a textbook, you have to say something different from all the existing textbooks. There is no point in repeating something just because you want an Indian textbook. You have to have a new perspective from that particular author. That has to be left to the individual.

It can be facilitated. If somebody wants to publish a book, maybe there can be a publishing house that helps.

shifting over to English took some effort as I had to practise

There is another level of writing, expository articles and such. Do you think we don’t see that as much in India?

AS: No, I think there are review articles written by Indians, and also expository articles.

Because that is another way to connect people who do research in India to people who want to learn.

AS: Writing textbooks itself will probably not solve this problem. Facilities in the universities are much worse than those in the research institutes. The undergraduates don’t really come in contact with active researchers very much. That probably will not be solved just by writing textbooks. You will have to change the system.

ability to cope with the fact that nothing is moving is hard

Maybe what I am saying is outdated in some sense. In our time, when you read a book by an author, and you solved a problem in it and the author was at your institute, you would want to meet the person. Even earlier, Harish-Chandra, for example, had already read Dirac’s book and it may have eventually led him to Dirac. So a book written by a practitioner living and working nearby may have some impact.

AS: That is true.

It is in that sense that I ask, not just for the sake of writing books by Indian authors but for sharing one’s excitement and passion in a different fashion.

AS: Yeah, that I agree. But that has to be done at the individual level.

What do you feel about the way science and mathematics are taught in schools today? Like the way a school curriculum is designed for physics and maths in terms of preparing students for research? What about colleges?

AS: The problem is that I don’t really know very much about how it is being taught in schools now. It is hard for me to comment on that. With colleges, it makes a lot of difference as to where the students come from.

You mean to say urban versus rural?

AS: Not necessarily. Which particular college they are coming from—colleges in some states are better than others—makes a lot of difference. So, preparedness, I would say, varies a lot between different places.

There is this big difference between exam writing in a curriculum learning system and research. In an exam, you have questions and you get a clear score and have some notion of where you rank on a particular day. But with research, there are a lot of dead ends and there is sometimes no clear question. Is there some aspect of the undergraduate curriculum, such as thesis projects, that you think can give people a flavour for that kind of research?

AS: I think most undergraduates will not go for research. So, it is hard to say that every undergraduate has to have this kind of training. But, certainly, an undergraduate thesis gives some flavour of what is involved in research.

I think one aspect of research that students have to learn is that most of the time they are not getting anywhere. What I have found is that among most students who ultimately fail to succeed, it is because they have a difficulty accepting the fact that sometimes things don’t work out. In college, if you are a good student, you will always get everything right. Maybe once in a while you make a mistake but typically you will get everything right. This doesn’t happen in research.

When you look back on your career do you remember particular problems where you were stuck for a long time?

AS: 90\% of the time I am stuck! [laughs] Only 10\% of the time things move. I remember, in my PhD days, for almost three years nothing moved. Something started clicking towards the end of my PhD.

How did you manage during those three years with that feeling of being stuck?

AS: Somehow we had a lot of friends, we had fun, and we used to go around and see places and not think too much about it; and simply hoped that things would work out. [laughs]

You had other avenues to endure this period.

AS: Yeah, exactly.

And you continued to attend lectures and talks?

AS: Exactly. I read lots of books and lots of review articles.

Do you feel the student community plays a big part there because you are all stuck “together’’ in a sense.

AS: I think it certainly plays a big part. You have to have a good support system.

It is something if everyone is stuck in [their] problems together, for there is some sense of solidarity in that.

most students fail to succeed because of their difficulty accepting that sometimes things don’t work out

AS: Yeah, exactly. I think many of the students I have found—very bright students—give up at that stage, when they are stuck. This ability to cope with the fact that nothing is moving is hard.

That is definitely a hard period. At Stony Brook, where do you think that sense of student community came from? Did the institutes play any kind of role in that or did it spontaneously emerge?

AS: There was a big Indian community and because you are a minority I think there is a support system in that.

at that time teaching itself was considered an achievement. Society as a whole valued teachers

And the support system really helped through those hardships.

AS: Yeah, I suppose so. As I said, we used to go sightseeing to various places.

Since many of you came back to India do you still do that?

AS: After coming back, we have not done it as much. [Laughs] Mathematics and physics have earned a reputation for being difficult subjects with very little career prospects even though they play a major subconscious role during the cognitive growth phase of an individual.

What do you suggest to change this perception about mathematics and physics?

AS: I don’t know whether I can really change the perception. Mathematics is there at various levels, like when you calculate in order to buy something. With higher mathematics, you cannot convince people that everyone should do it. And it’s a difficult subject—it’s like a new language and some people have an aptitude for languages while some don’t.

So whoever has an aptitude for it will take to it, and along with endurance they will manage?

AS: Yes, and the point is I think it’s not that if you study mathematics or physics then you have to stick to that. You can move into so many areas because mathematics and physics are used in building higher technologies.

That’s another point. The impression seems to be that you pursue mathematics as a research career and succeed at different levels, and in addition, the applications of mathematics are another reason for its pursuit. I also feel that teaching is another component. Now I do not know if I am right or wrong, but I think teaching seems to have taken a back seat to having to produce research papers.

AS: It has perhaps taken a back seat in the sense that in most of our universities and research institutes, promotions for example are based mostly on your research. But at the same time, in places with a substantial number of students, I would say teaching is necessary. If you get a bad grade in teaching, that will count against you. It is true that research is given the maximum priority for career advancement but teaching is important.

… it has taken a back seat. Teachers play an important role in your studies but because of the emphasis on research and producing a number of papers, professors have a different pressure that if they teach a course well, it will not contribute towards a promotion.

AS: Yes, the point is our own teachers also must have worried about promotions but at that time teaching itself was considered an achievement. Society as a whole valued teachers. Maybe that’s what has changed. Again, I think it varies from place to place, and I think in Kolkata probably good teachers are still valued. At least students look up to them and if there is a very good teacher in one college, others come to know about them.

The college gets a reputation!

AS: Exactly. This probably varies from place to place. I think in Bengal, my theory is because there is less industry, people don’t have any outlets; so you achieve by teaching and research.

And that’s why, you see a larger number of Bengalis getting into science.

AS: Yeah, this is one way of achieving.

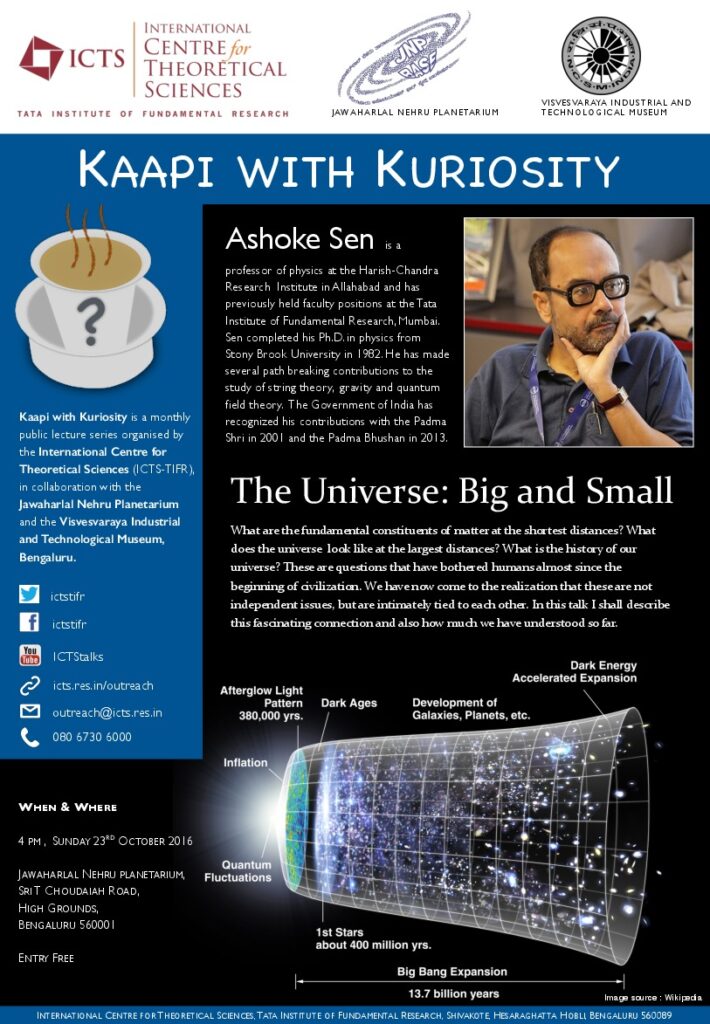

On the same topic of teaching, we have heard your lecture in Kaapi with Kuriosity,4 and have heard your lectures elsewhere. You are known for communicating ideas very well. Do you have any plans to write science books for younger people?

AS: Never thought really very much about it. At some point, I may do it but that requires a different kind of skill probably. I have written short articles for Resonance5 but not books.

String theory being your mainstay in research, how would you explain it to a high schooler or an undergraduate who has read popular science books, and wants to pursue it as it has earned quite a reputation, often described as a `theory of everything’.

AS: When you try to build a theory of nature, you always think of the smallest constituents of matter as particles. That’s the way standard particle physics is formulated. Like we think of electrons and quarks as the fundamental objects used to build other things. The basic premise of string theory is that those fundamental objects are not point-like objects but one-dimensional string-like objects that can exist in various modes of oscillation. These are very tiny strings. In current experiments, they look point-like but because of this one extra dimension, they can exist in various oscillation modes. Just like how a vibrating string can vibrate in different amplitudes, different harmonics and modes of each string appear as particles. So in a sense, you can say string theory is a theory of an infinite number of particles but can be thought of as different modes of a vibrating string.

you can say string theory is a theory of an infinite number of particles but can be thought of as different modes of a vibrating string

One of the features of string theory—and is the reason why we believe that string theory may have something to do with nature—is that one of those modes of vibrations mediates gravitational force according to the same laws that Einstein proposed in the general theory of relativity. So in a sense string theory automatically gives a theory of gravity even though you do not put it in, and it’s a consistent quantum theory of gravity which no other approach has succeeded in giving us. Developments since 1984 showed that some of the modes of the string can also possibly explain the other kinds of forces that we see in nature or the kind of elementary particles that we have, like quarks and electrons. The main hurdle is that the equations of the theory have multiple solutions but we have to find a particular solution that describes quantitatively (not just qualitatively) the properties of elementary particles that you have in nature. So far, the solutions we have found have a qualitative agreement with the properties of particles but not a quantitative one.

When you talk about elementary particles, most of them come with a charge, right?

AS: Not always. Like a photon for example. It is an elementary particle which is a carrier of electromagnetic force that has no charge.

The reason I am asking is whether there is a similarity between the charge associated with a particle and the gravitation associated with large masses.

AS: The similarity is in terms of fields. A charged particle produces an electric field and a point mass produces a gravitational field. When you put a field in a quantum theory, the field becomes a particle. For every field, there is a kind of particle. For an electromagnetic field, there is a photon which carries the electromagnetic field, and for the gravitational field, there is a graviton…. What you find in string theory is that one of the modes of vibrations of the string gives a graviton, which mediates the gravitational force.

String theory also appeals to mathematicians for its mathematical formalism. You are known for duality conjectures. What is the status of these S-duality conjectures and have there been interactions with the mathematical community in India or elsewhere?

AS: As far as I know everybody believes it is true. Duality is important because it’s a particular kind of equivalence between two descriptions of the theory. The two descriptions apparently look like two different theories. As classical theories they are genuinely different. However, as you go from a classical description into full quantum theory, these two turn out to describe the same physical theory. This means that if you identify some quantity that you want to calculate, the results appear to be very different when you calculate them from the two different descriptions. When you require that those results are the same, this can sometimes lead to non-trivial mathematical identities. The conjecture you are talking about is one set of these particular identities, and some mathematical property had to hold for the said duality to be true. If you find that those properties don’t hold then that means the duality doesn’t work.

You proposed one of those identities.

AS: I gave one of these series of identities and I checked it for the simplest case which was the easiest to check because you could explicitly solve it. Basically, you have some 4n dimensional non-compact spaces where n is any integer, and this identity is about the existence of square-integrable harmonic differential forms in those non-compact spaces. The conjecture tells you exactly how many such harmonic forms will be there and with what properties. I checked the conjecture for n=1. This duality conjecture is from 1994. There was a paper in 1996 or so by Segal and Selby which proved a part of this conjecture for general n. I don’t think a full proof has been given so far.

Science is logical but scientists are not necessarily logical

In our interview with Don Zagier6, there is a story that Atiyah described a conjecture of Witten in a Bonn-Arbeitstagung Meeting. Maxim Kontsevich had just joined Don Zagier as his student. Don introduced Kontsevich to Atiyah as the person who would prove these conjectures. Kontsevich sketched out the idea for a proof to Atiyah on a boat-ride, which formed Kontsevich’s thesis. This work not only earned him his Ph.D. but also a Fields Medal. Of course, proofs like that don’t happen very often but that’s the kind of mathematical collaboration I was asking about. A similar connection in which you are mentioned in Zagier’s interview is in a conference on modular forms and black holes. He attended your lecture where you mentioned a conjecture about wall-crossings.

AS: It was an observation, not a conjecture. It was a specific observation about counting done in a moduli space. You are counting the number of states of a system and this number depends on the moduli parameters that you can vary. Since it is a counting problem, the number of states remains unchanged as it is an integer. But there are these “walls’’ in the parameter space that when crossed, the number of states jumps. So that’s what is called wall-crossing. But in this particular system, there is something strange that the number jumps in a specific way.

For example, let’s imagine that you have a function like \frac{e^{2\pi i v}}{(1-e^{2\pi iv})^2} where v is some parameter. Say that the number that you are counting is the Fourier expansion coefficients of this function. You have to expand this function in the power series of e^{2 \pi iv} and pick up the coefficients. It’s easy. You get \frac{x}{(1-x)^2} is x+ 2x^2+ 3x^3 + \cdots. You just expand it out and you see that the coefficient of e^{2\pi iv} is equal to 1, e^{4\pi iv} is equal to 2, and so on. So this is the counting that you will get on one side of the wall.

Now you take the same function \frac{e^{2\pi i v}}{(1-e^{2\pi iv})^2} and expand it in a different way where you first multiply both numerator and denominator by e^{-4\pi iv} and then expand this in powers of e^{-2\pi iv}. So that the corresponding expansion now has e^{-2\pi iv} +2 e^{-4\pi iv}+ 3e^{-6\pi iv} and so on. The coefficient of e^{-2\pi iv} is 1, e^{-4\pi iv} is 2 and so on but all the positive powers of e^{2\pi i v} have zero coefficients. So it gives a different counting. These two different ways of expanding the function turn out to be the result on two sides of the wall. It happens in many cases but for this particular class of systems, the wall crossing followed this specific pattern where you got different answers from expanding the function in two different ways. Zagier made the connection that this phenomenon appears in the theory of mock modular forms. He then went on to write a detailed paper with Atish Dabholkar and Sameer Murthy explaining the relation between Mock modular forms and number of states of a certain class of black holes in string theory.

On this note, Einstein famously said imagination is more important than knowledge. What does this mean to you?

AS: That may be a little too abstract. I think imagination is certainly needed. Knowledge is what you already know, which is important because unless you have the knowledge, you really don’t know how to make the next jump. But doing science is not like that, where you process that knowledge and go to the next stage. Science is logical but scientists are not necessarily logical [laughs]. Scientists progress by some irrational intuition. Once you get a result, then you can have a logical framework. In that sense, you need imagination.

There is a `personal factor’ of the scientist.

AS: Exactly. The rules in science are very clear that you have to go from step A to step B in a logical fashion, but scientists don’t necessarily proceed like that.

They always wait for a flash or something like that. Something clicks. Have many of your own discoveries happened like that?

AS: Yeah, I think so. Maybe, in principle, all of those you could have arrived at in a logical fashion. But that’s not the way I arrived at those conclusions.

Institutions bring people together, people with similar minds and interests

String theory, as we know so far, does not have any experimental confirmation but this is still called a theory in physics. At what point does a hypothesis start getting called a theory and what are its requirements?

AS: We don’t distinguish much between hypothesis and theory because in science everything in essence is hypothesis. Even the standard model which you know is so successful is not the final story. You can call it a hypothesis, a theory, or a model. The name is not very important. String theory predicts gravity, but gravity was known prior to string theory. The reason that people are still excited about string theory is that this is the only consistent formulation of a quantum theory of gravity. We don’t know how to combine gravity and quantum mechanics in any other way and so far there is no logical inconsistency in string theory. There are many ways for it to fail. You test it by arriving at some mathematical identities which, if false, would mean that there is an internal inconsistency in string theory. Yet, we always find that those mathematical identities hold even if they were not known earlier.

So that’s the main strength of string theory i.e., that it’s a consistent theory of gravity and it’s internally consistent. And there is no logical flaw so far. Whether it will make a connection with nature in the end, we don’t know. But whatever may eventually describe nature, that theory should be mathematically consistent and string theory is currently the only consistent theory. While gravitation has been explained quite well by string theory, particle physics, as I said, is only qualitatively but not quantitatively explained. The theory has multiple solutions, with each corresponding to particles with different properties. Which solution describes reality is not known. That’s the main difficulty in connecting string theory and particle physics.

In some sense, the essence of string theory as you said is to replace particles with strings as fundamental building blocks. Was there a mathematical or physical motivation for this idea?

AS: In the initial days when string theory was born, people were trying to use string theory to describe a theory for strong interactions. Then, one realized that strong interactions are better described by quantum chromodynamics but later on, people found that string theory also explains gravity. That made it a natural candidate not for just strong interactions, but for a more fundamental description of nature which includes gravity and all the other elementary forces.

But why strings instead of point particles?

AS: That was more phenomenological. People observed something about strong interactions in experiments about the particle spectrum that looked like the particles were coming from strings. So it was accidentally found. In fact, the way string theory was discovered was that people first wrote down an answer which looked nice. They didn’t know where the answer came from and then found that that answer is produced by a scattering of strings. So string theory was not discovered by saying that “Okay, I postulate that point particles are replaced by strings.’’ It was more of a random walk where you explore various things and you find that ultimately you have arrived at the theory of strings. In the first paper on string theory that was written, there was no concept that it is establishing a theory of strings. It was just an answer which had some nice properties.

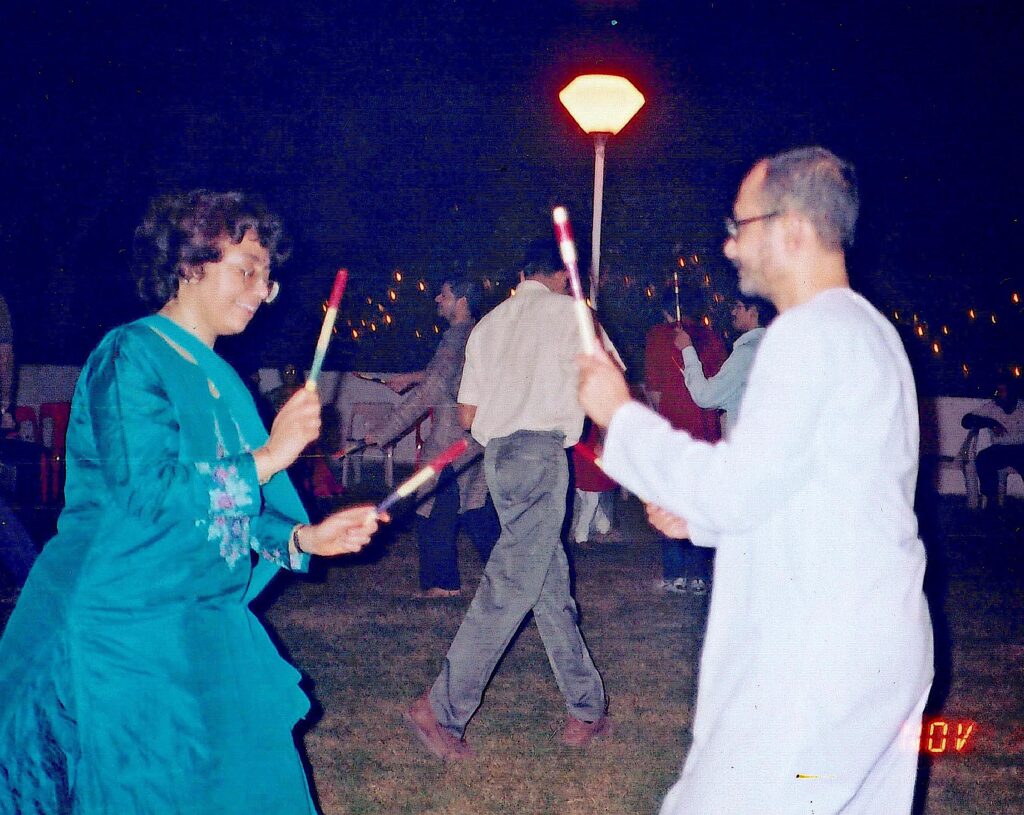

You are quite well-travelled thanks to your research, and one of the things that I do remember is that you were present in China at the time of the Tiananmen Square massacre. I remember this basically because I was at TIFR and this was in the newspapers at the time after you returned. Can you recall your memories from that time?

AS: We were there for an instructional school. Everything looked quite peaceful. We had even gone to see the square and met the students who were demonstrating. It was during a break in the school that they took us to some other city by train where we stayed overnight. When we came back the next morning we learnt that the previous night this event had taken place, and we actually saw a lot of destruction on the road.

Are there any kinds of books that interest you?

AS: I read novels, like Salman Rushdie’s works. Haroun and the Sea of Stories, Midnight’s Children, and Victory City, to give a few examples. I am saying this because I am reading Salman Rushdie’s books right now. Other times, I read other books; and then I may also mention authors like Doris Lessing.

Is there any Bangla literature you read?

AS: Bangla books of course, like old novels. I used to read everything when I was young but now I read once in a while. I don’t have that many Bangla books and now, because of my eyesight, I mostly read on Kindle and not physical books.

What are your hobbies? How did you spend your time during lockdown? We hear from your contemporaries that you love cooking. Is that one of your favourite times when you think about physics?

AS: [laughs] I don’t know. I like cooking because I like eating and during the lockdown, there was no option, and so I had to cook. During lockdown, the thing I remember is cooking, cleaning, and washing pots.

Since your fondness for eating doesn’t quite show in your physical appearance, I have heard your friends saying that all the extra food that you eat appears as papers in Nuclear Physics B!

AS: [laughs] That I don’t know. I generally like walking, and used to walk very regularly but that’s all.

Is that a time you also think about physics?

AS: Yeah, I think, in the background maybe things are going on, but not in an active sense.

In one of your talks in 2016 you had mentioned that the INO – the Indian Neutrino Observatory – could play a big role in understanding neutrinos and dark matter. A recent TIFR website announcement says that it is now at the feasibility stage. Could you share your views on that?

AS: My understanding is that it has been stuck for a long time because of the environmental clearance issues, and a lot of politics; so it’s doubtful that it will ever happen. It’s probably already too late because lots of foreign places are building neutrino observatories. I think when it started, India had an edge because it could have discovered new things. Now it’s probably too late to compete with other places.

Did you ever consider taking on administrative positions like directing a research institute or heading a science society in India or abroad?

AS: [laughs] Definitely not.

That’s because you feel you are not cut out for it?

AS: Yeah, you need different kinds of skills to hold administrative positions.

Your work has won a lot of accolades and awards. What do they mean to you? Do they influence your mind as a thinker?

AS: I don’t think they influence my mind as a thinker. It is certainly an encouragement for the research, and that other people appreciate it. I probably would have thought in the same way even otherwise also as far as the research is concerned.

You won the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. You were amongst the first awardees.

AS: I was very surprised. I mean the first award was given to nine people. The others are all really top people in science. It was a pleasant surprise to be in that company.

Do you have any favourite among your research works that holds a special place for you personally?

AS: It was somewhat unexpected that a duality conjecture you make by a simple observation can actually have non-trivial consequences leading to complicated mathematical identities that can be tested. This is important especially because string theory doesn’t yet have experimental verification, but there are many ways in which string theory could be ruled out just from considerations of internal consistency.

Are there other aspects of theoretical physics that you think are promising directions of research, especially for someone who may be non-inclined towards string theory, and who could consider something as being potentially valuable in terms of research direction?

AS: One has to certainly explore all directions before the breakthrough happens; it is very hard to predict which areas might lead to a breakthrough. Even for Heisenberg, before he actually moved into quantum mechanics, nobody could have predicted that that kind of work would eventually be so important. Breakthroughs by definition cannot be predicted because if it could be predicted then those who predict it will probably achieve the breakthrough. So, I think what one can say is that we have to keep an open mind, that people should explore different areas and then maybe one of those will eventually provide a breakthrough. It’s only afterwards that you can reanalyse and say why it was important. The subject moves in unexpected ways. Even completely different areas may have a connection with string theory.

Thank you so much for your time. It was enjoyable.

AS: Yes. I enjoyed it too. Thank you. \blacksquare

Footnotes

- A public school funded by the state government. ↩

- A government-aided school is a private school with partial state funding. ↩

- a public school funded by the city. ↩

- Available at https://www.icts.res.in/outreach/kaapi-with-kuriosity/universe-big-and-small. ↩

- https://www.ias.ac.in/listing/bibliography/reso/Ashoke_Sen. ↩

- https://bhavana.org.in/speaking-the-language-of-mathematics/, Bhāvanā, 7(2), 5–30 (2023). ↩