![Nambiar and his autobiographical sculpture of the cactus [partly seen].](https://bhavana.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/BalanNambiar-1024x536.jpg)

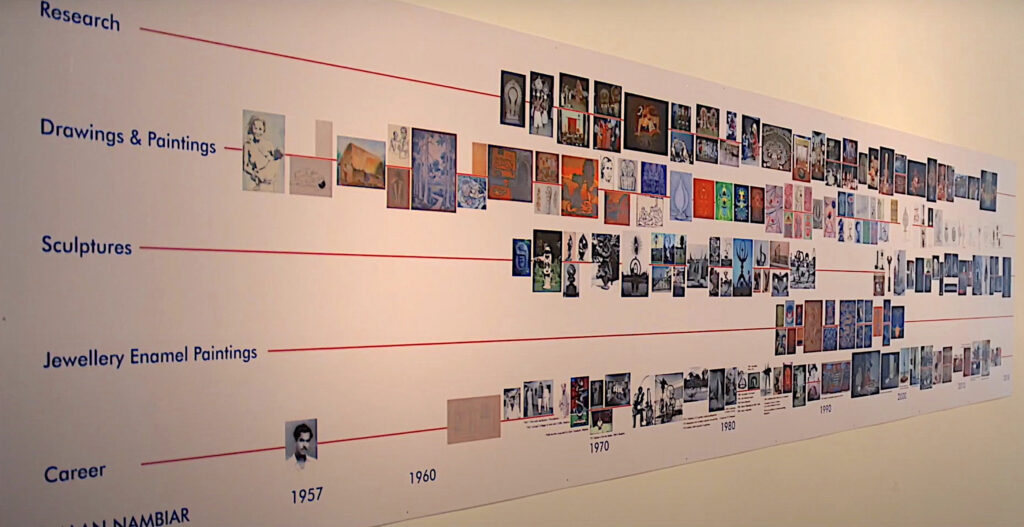

Balan Nambiar is a much sought after Indian artist with a rich and wide-ranging experience of over six decades. Known basically for his exquisitely crafted stately stainless steel sculptures, his efficacious hands have literally touched every form of art. Several one-man exhibitions of his art work on the national and international circuit have won him richly deserved acclaim and recognition.

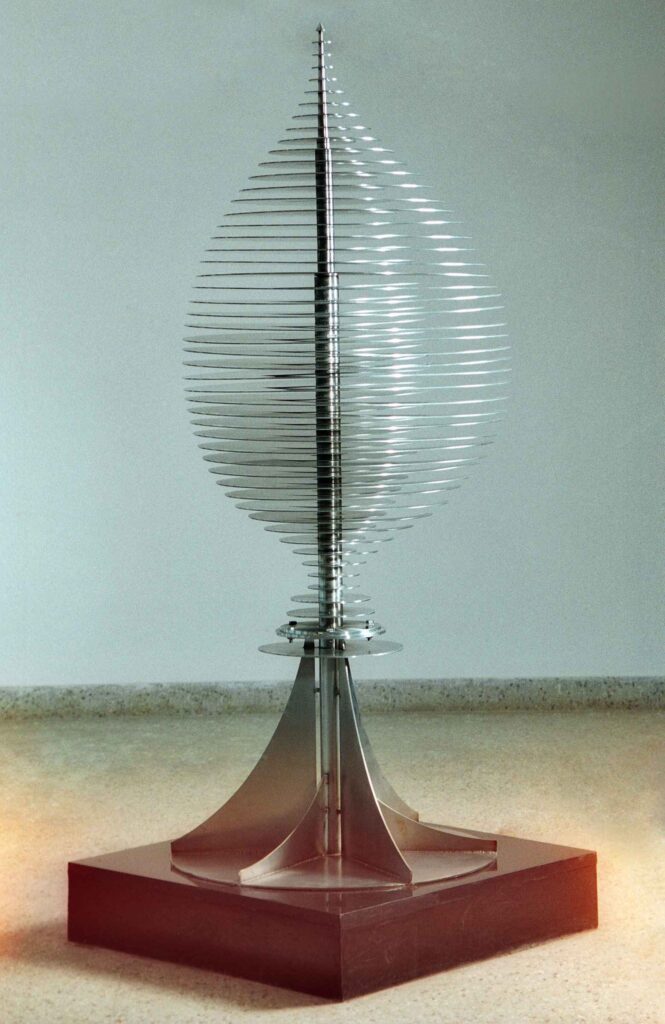

Capturing the spirit of ancient ritual performances of the coastal regions of Kerala and Karnataka through his strong, symbolic and expressive art, his major contribution also lies in the deep study and documentation of these long traditions, passed from generation to generation. His evocative sculptures reflecting mathematical attributes like the golden ratio, Fibonacci numbers or the fractals, adorn some of the leading scientific institutions and industries across the world.

Each one of his works tell their own beautiful story behind their creation, and it was a unique experience to hear them straight from the creator himself. Sitting spellbound and listening to him at his quiet home in Bengaluru, some of the stories we heard are retold here, as our humble tribute to a great artist.

Balan Nambiar: A biographical preamble

For someone, who, even late into his teens, did not know that there could be a career pursuing art to transform into an accomplished world-famous artist, the journey is a likely succession of fortuitous events. From a farmer ploughing the fields in a remote Kerala village to becoming an artist of international repute treading across the world with his unique art creations, the journey of Balan Nambiar is a fascinating story.

Balan hails from a matriarchal farmer’s family. This humble beginning seems naturally embodied in the humility of his disposition when he lets his art, a language of varied images sans words, speak for itself. He received his early education in Kannur district in the northern part of Kerala, studying up to the SSLC [Grade 11] level. He began his career as an art teacher in a high school, and worked there for a year before he got a job in Madras with the Railways. He worked for six years as a draughtsman designing signal equipment. But all the while, he continued with his passion for painting along with his work, and participated in many exhibitions.

His first big break came during the Mysuru Dasara exhibition in 1957, where one of his paintings titled Still she wants to work won the first prize. It was during this time that K.C.S. Paniker, the then principal of the Government College of Fine Arts, Madras, came to know about Balan through a catalogue of the Dasara exhibition. He saw Balan at one of the later exhibitions and after seeing his paintings, said that Railways was not the place he should be in and that he is cut out for a career in art. That was the starting point for him, going from an entirely non-artistic background to taking up art as a serious pursuit.

Balan’s familiarity with Theyyam began, as he says, “from the time of my birth”, because his own house had a shrine. This ritual performance used to be conducted every year in the last week of December. Born on 12 November 1937, he was therefore exposed to the Theyyam ritual very early on. Colloquialized as Theyyam, it derives its root from the Sanskrit word Daivam, meaning `god’. In this, the performer invokes the blessings of the god, the divinity in the form of matā, pita, guru, daivam in that order, is possessed by the spirit and then proceeds to dance to the vigorous accompanying drumming. The interesting fact is that the ritual dancer combines many artist avocations: a painter, a craftsman, a costume designer, a choreographer, a musician, a drummer and a person with some sort of extra mystical ability that can withstand very odd situations, like carrying heavy weights, or walking through the fire. Balan felt this ritual to be a combination of several art forms. Watching this performance repeatedly from his early childhood became a big source of inspiration for him. When he later started taking courses in the College of Fine Arts in Madras, the motifs and symbols of these subjects spontaneously came into his paintings and sculptures.

After Paniker’s sound advice, it would be a couple of years before he could take the plunge because it was a period when his financial situation was not very good. But, after about a year or so, he resigned from the Railways in 1967, and joined the College of Fine Arts in Madras.

Balan had received a couple of awards for his paintings, and even had a one-man exhibition before he joined the fine arts college. He then sought admission for a painting course at the time of submitting the application form and, fortunately, was directly admitted to the second year of the five year course because of his possessing a background in art. During his first year at college, he did a series of paintings titled Seasons based on Ṛtusamhāra of Kālidāsa, depicting the six seasons. They were large paintings, about 4 ft by 6 ft and were not conventional realistic paintings, but were more expressive in style and very bold with lots of pigments and colours employed.

In the foundation course he had to do painting, sculpture, metal work, graphics and enamel and study various topics including study of the history of art. Balan joyously recalls that he felt like a duck in the water when he started doing sculptures. He started doing so well and was so spontaneous that he eventually switched over to the sculpture course from the painting course, and specialized in it for three years.

Balan’s works are predominantly inspired by the ritual art forms, and recreated in his own way as he liked to symbolize them. He wanted to document these ritual art forms for archival purposes and also for his academic research, and writing articles about them.

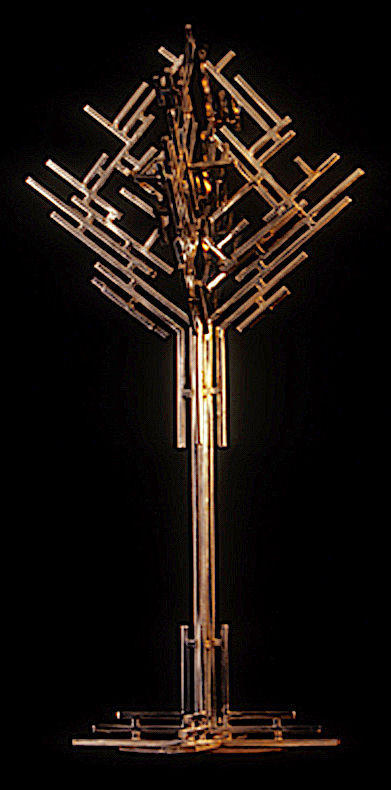

Balan’s career in sculpting, which started with the clay medium, progressed to cement, then bronze, and then mild steel. He got a special opportunity when he was in the final year. For five months, instead of attending the college, he was doing experiments at the metallurgy department of the Indian Institute of Technology in Madras, casting bronze sculptures and welding. It meant a great opportunity for him to learn the technicalities of metallurgical knowledge.

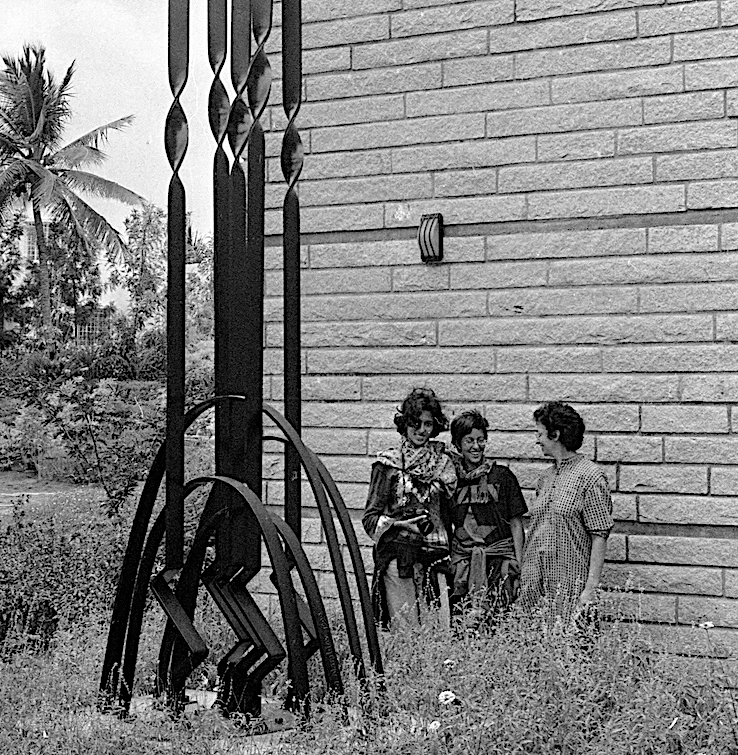

The year 1975 is a landmark in his career. He had a one-man exhibition of garden sculptures in which there were 24 sculptures in mild steel. The tallest was 18 ft in height and the smallest was taller than his height of 6 ft. It was probably the first of its kind in India. The exhibition was very successful in that 12 sculptures were sold, of which four of them are now in the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi.

Balan did a lot of mild steel sculptures initially but was unhappy to see his works, collected by establishments and Institutions, not looked after properly and damaged or destroyed because of corrosion or rust. He then switched over to the more durable medium of stainless steel. From the year 2000 onwards, he has only been sculpting in stainless steel. In his career he must have done at least 130 sculptures, all taller than his height.

By his own description, Balan’s sculptures are symbolic in an abstract way, visualising certain ideas from his own perspective. The ones symbolizing growth as inspired by his farming background and those with ritual motifs are some of his favourites. He made a sculptural cactus in the 1975 exhibition and his fascination for the cactus is that he sees it as a plant which asserts its existence. In that sense, he says that the cactus is almost like his autobiographical symbol.

From his college days onwards, unto this day, he says that he hasn’t been a part of any group. His philosophy of freely sharing knowledge has meant that there are always students of diverse ages around him, from a six-year-old aspiring sculptor to those older than him. He fondly says, “I would like to see, either in my lifetime or later, that some of my students become greater than me. That should actually happen, and that generosity or mindset is necessary for a teacher.”

Most of Balan’s publications are about rituals and ritual as an art form. His view is that throughout India there are artistic treasures created by a succession of traditional rural artists going back over centuries and millennia. As an artist, he felt that his job was to seriously involve himself by taking an interest in these long drawn local investments and recreate as well as document their art, thereby paying homage to all those artists of the past. From that point of view, his contention is that there are plenty of things left to do for both artists and the society, that one lifetime is not enough to pay homage to these dedicated rural artists.

Balan was a close witness to one such event in 1975, showcasing an elaborate construction mentioned in one of the millenia old texts. Spanning over a couple of weeks, the main part was the construction of Agnicayana, a bird-shaped fire altar, recorded as Śyenaciti in the ancient Śulba-sūtra texts. His inner circle involvement as an observer at this event inspired him, some 15 years later, to come up with Śyenaciti as a logo for the National Institute for Advanced Studies (NIAS) in Bangalore1

Balan’s research spans across Kerala and two districts of Karnataka which are in the coastal area. In these regions he has spent several weeks on end, visiting almost every village during the period of the rituals, from their elaborate preparation to completion stages, and is fairly familiar with hundreds of ritual art forms. Balan is also a great photographer. Many of his photographs are published in international photographic journals.

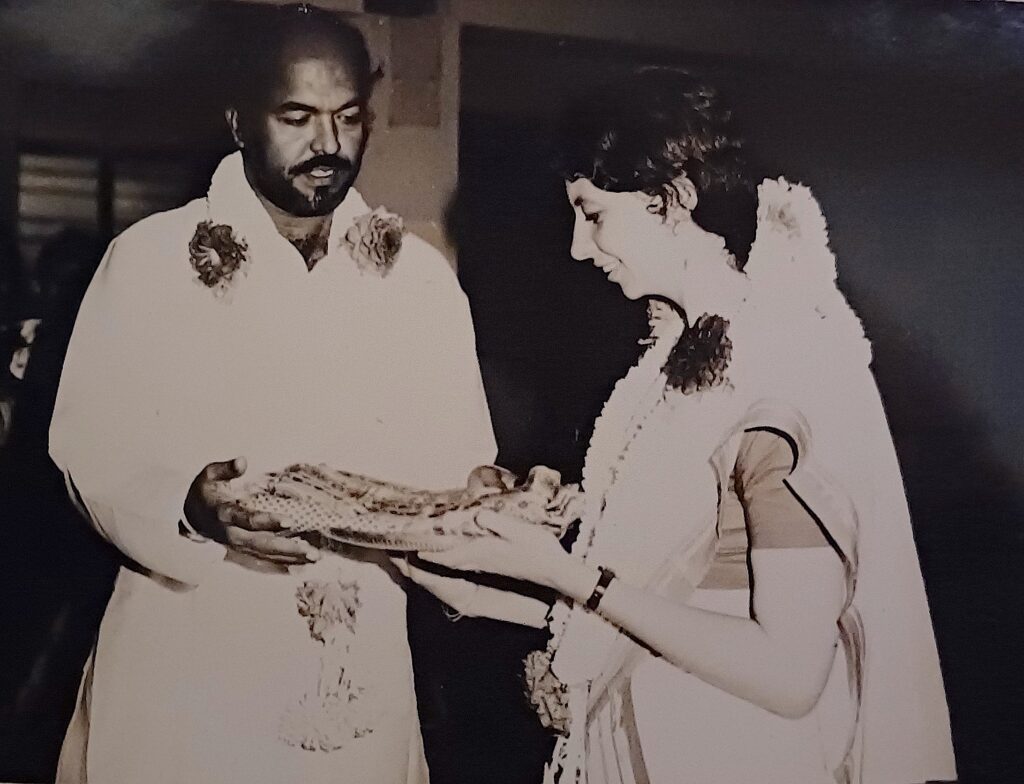

Balan’s work with enamel has a compelling story to relate. His deep interest in reading, visiting libraries and art exhibitions during his free time is what led him to find another love of his life. He met his wife Evelina De Poli, a nuclear physicist, in an art museum in Munich in Germany where they happened to find themselves spending time viewing the same paintings for almost the same lengths of time. That opened up a conversation between them, sharing their impressions, eventually leading to their marriage in 1980. His Italian father-in-law, Paolo De Poli, is considered the greatest enamel artist of the twentieth century. He lived for 91 years from 1905 to 1996. He had a huge enamel studio on five floors consisting of a basement, three floors and then an attic. It is interesting to read more about this, in his words, in our following interview with him at his own studio and home in Bengaluru.

Balan says with gratitude that he must be thankful to Texas Instruments because when they discussed making the sculpture, he wasn’t asked for a drawing or the size. He also got 40 percent of his payment in advance when his drawing was not even ready. The possibilities were innumerable and he had full freedom to come up with an idea that was in consonance with his own.

The sculpture that Balan made for the Timken factory in Electronic City in Bangalore is about 19 ft high and is one of his finest sculptures. Later he did a 21 ft high sculpture for the Indian Oil Corporation in Delhi, and another one for the Bank Note Paper Mill which is 23 ft high, 4\frac{1}{2} tons in stainless steel, which is the tallest he has done to date.

Balan believes in the durability of his created work. He is of the view that the urge for creativity can be satisfied by creating a sculpture in any medium but if one wants to preserve for posterity and show it to the society at large, or to the coming generation of students then one has to use a durable material. Balan’s passion for art is very inspiring. He says: “If you give me raw material in sufficient quantity, and some means by which I can subtract or add to it, I can make sculptures. I could go on making the sculptures 18 to 20 hours a day continuously.” With such a vast and varied experience, and creative ideas pouring out of his active mind, Balan’s energy to explore, and dedication to his art is rare and unique.

It is exciting to talk to an artist who has worked on several different aspects that encompass the word `art’ in its entirety. You have a large collection of paintings, sculptures in different mediums, photographs, all displayed across the world under your name. In a sense, you are a born artist, born in a family of farmers. In retrospect, were you early in seeing farming as an art form?

BN: I have thought of it very often. You see, as a child I used to go to the field with my uncle, and later I also used to plough the field. I was fascinated by the way the plough line goes starting from one corner, along the outer rectangle first and then spiralling towards the centre of the field going along smaller and smaller rectangular lines. The spiralling went clockwise or anticlockwise, shifting from the outer rectangles to inner smaller and smaller rectangles, towards the centre. That was perhaps the first mathematical pattern I observed as an eight-year-old child.

Then, after the seeds were sown, we would rush to the field the next day to see if the seeds had sprouted. It took about two days to sprout. In another three days you would see a blade of grass; then a second blade, a third one, and eventually in about three months you got the new seeds coming out. That again was very fascinating for me. It stayed with me all along and that is how my sculptures of grass and a rice plant came about. I wanted to symbolise the process of growth. This is how my being a farmer’s son later reflected in my art.

True. It is an absolutely fascinating process to follow growth over days and weeks. What were your own years of growth like?

BN: I lost my father when I was two years old. Since I come from a matriarchal system, there were my maternal uncles with whom I spent a lot of my younger days. They were fond of reading Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, Bhāgavata, Yogavāsiṣṭha and Devī Mahātmya, and other old texts in Malayalam versions. I have read all of them several times. My maternal uncles were my guardians. They helped me in every respect. I didn’t miss my father at that time. I didn’t realize it till I became a father myself and enjoyed my daughters’ affection. Only then I became aware of what I had missed.

All my life I have generally been led by the instincts of mathematics, interest in classical music, interest in literature, and the reading habit that I had developed from high school days. I learnt in a Malayalam medium school. One of my teachers, Shri Kelan Master, a Malayalam pandit, encouraged my reading habit. He used to get books in his name from the school library and give it to me for reading, and when I finished reading it, I had to write a synopsis of about two pages, and show it to him. His comments on my notes were inspiring. My mathematics teacher was also very good. When he found out my interest in it, he encouraged me, especially in geometry and algebra. I was good at them. Drawing was another subject I was fond of. This is how I grew up.

What about your schooling?

BN: I studied up to SSLC, that is, 11th Standard. Then I went to Calicut to study in a polytechnic,2 but I was late and couldn’t get admitted there. Then my uncle told me not to waste time and asked me to join a typewriting and shorthand course. From the window of that typing institute I could see the other building where drawing classes were going on. I went there out of curiosity and met the teacher. He asked me, “Are you interested?” and I said, “Yes”. He gave me a drawing and asked me to copy it. I drew it with pencil, very spontaneously and without using an eraser. He saw it and said, “Why do you waste your time in learning typing and shorthand, why don’t you come to the art classes?”

I discontinued shorthand classes and used that money to join the drawing class. This was in July 1956, and in September there was an examination by the Madras Government. My teacher asked me to sit for this examination. I hadn’t told my uncle as I didn’t have the money to pay for the examination fee. My teacher said, “Don’t bother, I will pay the fee for the examination.” I appeared for four examinations (three higher grades and one lower grade) and passed those. Luckily that was enough to become a drawing teacher in a high school. Then I went and told my uncle, “Forgive me! I didn’t do shorthand but I did this drawing course”. Immediately he said to me, “You did the correct thing. I didn’t want to see you as a stenographer either”.

While I was working as a teacher, I learnt machine drawing and applied mechanics mainly through self-study, and I passed some examinations that helped me get a job in the Railways in Madras in 1959. With my desire to study polytechnic still there, I joined a private institute to study part time for a Diploma in Engineering. It was a three year course. All along I continued with my drawings and paintings.

So the inclination towards art was a constant presence even while you worked in the Railways.

BN: Yes. Most of my spare time, I either spent on painting, or visiting art exhibitions, or attending music concerts or at the libraries in Madras. And I participated in some all-India exhibitions of paintings and won a few awards too.

Almost at this time, I met Dr. Karl Pfauter, then German Consulate General in Madras, who took a keen interest in my career and used to invite me very often to his residence to participate in receptions, and through him I met several Germans who were working at the Indian Institute of Technology in Madras. This acquaintance helped me a lot in my artistic career later.

When I started doing sculptures, I felt like a duck going into water.

Meeting K.C.S Paniker, then principal of the Government College of Fine Arts in Madras was a landmark that changed my life. I met him for the first time in 1962 in an art exhibition. Seeing many of my creative works he advised me to leave my job in the Railways and take up art as a full time career. It was then that I began contemplating joining the College of Fine Arts.

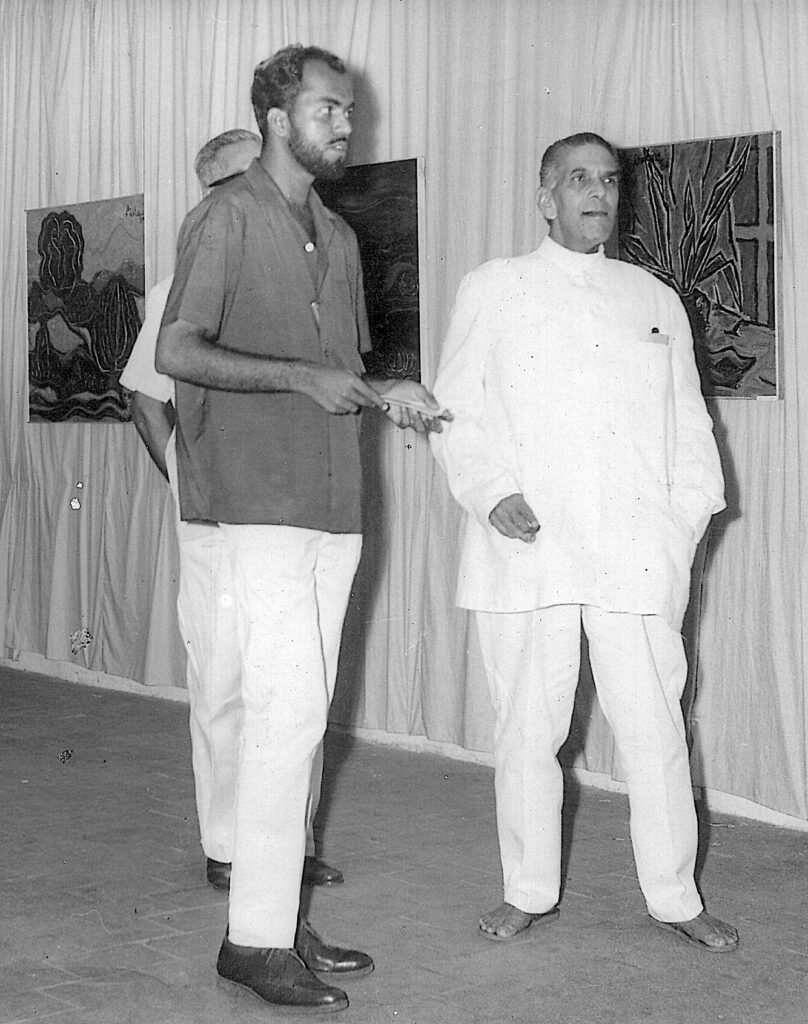

It took me another couple of years to make a final decision to join the College of Fine Arts. But before joining the college I had my first one-man exhibition of paintings in Trivandrum in Kerala. In fact, the introduction to the brochure of this exhibition was written by K.C.S. Paniker. It was inaugurated by then Kerala Governor Bhagwan Sahay. He took some special interest and invited me to Raj Bhavan3 for tea. He, a Kashmiri, too was a painter, and he showed his paintings and discussed them with me.

Because of my background in art, I was directly admitted into the second year of the five-year art course. From that point till today, I have been a freelance artist. When I applied for the admission, I had sought the painting course. After the second year we had to decide on the subject we had to study for the Diploma. During the foundation course we had to study all the subjects: paintings, sculptures, graphic art, art history, and metal work. When I started doing sculptures, I felt like a duck going into water. During that time, I made a sculpture of a mother goddess in clay, inspired by Theyyam. When it was in clay, Dr. Walter Breuer, then Director of Max Mueller Bhavan in Bangalore, who was on a visit to the College of Arts, expressed interest in buying it. I converted it into concrete. Now it is in Bremen in Germany.

For the next three years I specialized in sculptures. Some of the larger sculptures were 8 ft to 9 ft in height. I couldn’t cast all of them in cement because I didn’t have the money. But I made them in clay and took photographs. I did some sculptures in 1968 when there was an international industrial fair in Madras. My sculptures were displayed there. After the fair was over one of the sculptures, titled Moorthy, was acquired by the Madras Museum. The money I received for my one sculpture was more than my one-year salary if I had continued in the Railways. That gave me confidence to be a freelance artist.

Then onwards every year I had my one-man exhibitions and sold my works and lived on the income earned from them. Then a big transformation happened in the final year. In the fifth year, through an introduction of the German Consulate General who was fond of me, I got an internship in the metallurgy department of IIT (Chennai) for five months. I was supposed to be in the college, but the college professor gave me attendance which allowed me to spend my time in IIT. Several bronze sculptures were done during my student days.

Was it the first time you started doing metal sculptures?

BN: The experience I gained in the metallurgy department of IIT—learning a scientific way of welding and bronze casting—has been my asset. At that point of time, the Institute of Indian Foundrymen asked me to present a paper on conventional methods used for casting modern bronze sculptures. That was my first paper. Now it may seem very amateurish, but it was very interesting at that time.

I decided to leave Madras. After finishing the final examination I took a 6.30 pm train to Coonoor. I had some friends there, and I stayed there for one month just wandering. After one month, I came to Bangalore. Max-Mueller Bhavan’s then director, Dr. Walter Breuer, asked me to stay in his house as he was going on holiday for the next two months. I stayed in his house. I had first met him in Madras where he had bought my sculpture of the mother goddess.

I went back to Madras five months later and vacated my flat. When I was in Railways, I was paying the rent regularly. But there were some discrepancies when I was in college. I used to get a small scholarship of Rs.100 per month, and the rent was Rs.60; there used to be some delay in getting the scholarship on time which resulted in a delay in paying the rent. I got a lawyer’s notice that if I didn’t pay the rent, I will be evicted. I promptly responded by a registered reply that I am getting a scholarship, and I will pay the rent as soon as I receive the scholarship amount. This went on for about six to seven months. When I got the scholarship amount in lump sum, I went and paid the entire rent. Then I asked the flat owner, “Why did you send the lawyer’s notice every month?”. He replied as a matter of fact: “My son has become a lawyer. He wanted to gain experience.” When I vacated the house, the flat owner said, “Take whatever furniture you want as a token of best wishes.” So, I took one table and one cot given by my first flat owner as a gift. I still keep them proudly!

So you came to Bangalore after completing the arts course. Which year was that?

BN: I came to Bangalore in 1971.

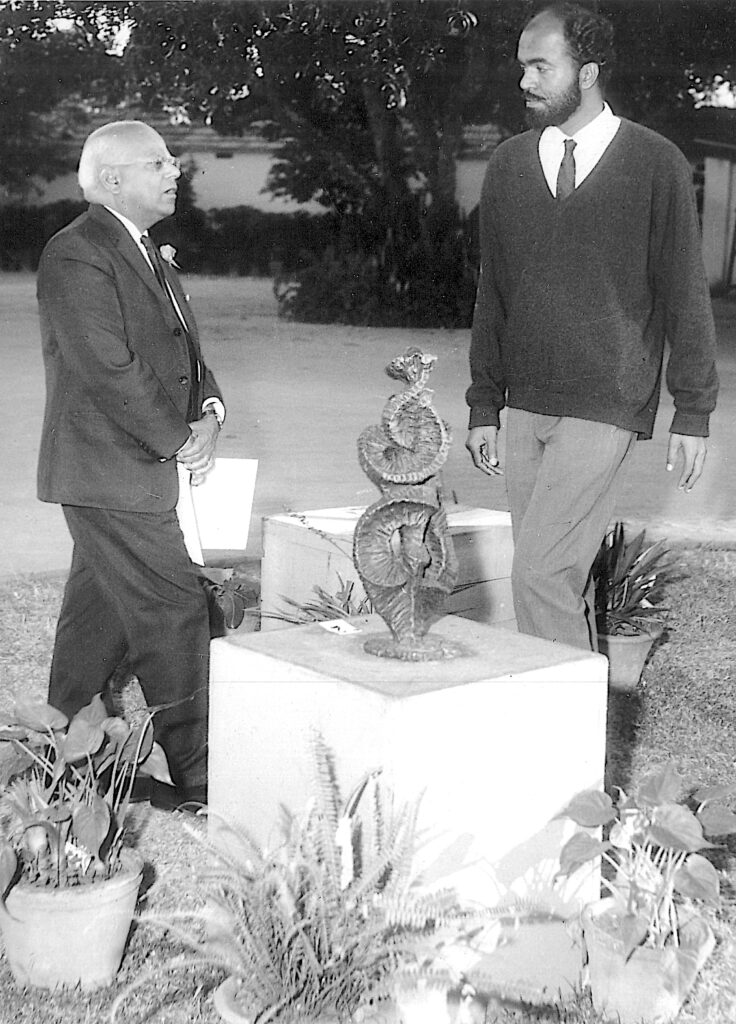

Another landmark in my artistic career was the holding of a solo exhibition of garden sculptures in 1975 in the front lawn of Hotel Ashoka, Bangalore. There were 24 sculptures, all made in mild steel, the tallest sculpture being 6.2 metres high and the smallest one about 2 metres high. The exhibition was well received: Some works were acquired by public institutions. In the following year, four of them were purchased by the National Gallery of Modern Arts, New Delhi.

Something similar to what happened during my first solo exhibition in Trivandrum in 1967, the Karnataka Governor Mohan Lal Sukhadia visited my exhibition of garden sculptures and he took some personal interest in me. He invited me often to Raj Bhavan for tea and discussion. No political discussion, we talked on many other subjects. I came to know that he had a Diploma in Engineering before he plunged into politics!

One day, I was talking to three eminent Malayalam writers, including M. Govindan, G. Shankara Pillai, and Kadamanitta Ramakrishan about my experience of watching Theyyam and ritual dances. Shankara Pillai who was the chairman of Kerala Sangeeta Nataka Akademi, said, “Balan, you have to write your experiences. Nobody knows about it. You have first-hand experience.” So, I wrote an article in Malayalam about my experience of observing Theyyam of Kerala and Bhūtas [Bhūta Kola]’ of South Canara in coastal Karnataka. I presented that paper in a seminar. Later it was published as part of a Malayalam book by Sangeetha Nataka Akademi of Kerala. That was the first ever article written on this subject as a comparative study. That was very well appreciated.

Mrs. Valentine Stache, the wife of the then director of Max Mueller Bhavan in Bangalore, was a scholar in Sanskrit and Pali, and she asked me for some help. I escorted her to see some of the Theyyam and Bhūta performances. She would give me her camera to take photographs from the areas restricted for foreigners. Mrs. Stache got me a camera that she had brought from Germany later and I started taking photographs on my own and making slides which I used for presentations.

So you learnt the art of well-researched documentation as well…

BN: Yes. I am grateful to Dr. Valentine Stache for her advice on academic research and documentation.

The greatest of the great opportunities came in Bangalore, when Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay came to know about me and invited me to her place. I had a projector and screen, and I took all these to show her my slides. She spent several hours with me, discussing my interest in these topics. Hailing from Mangalore she was familiar with them. She said, “Balan Nambiar, I want you to give a presentation about your documentation at the India International Center (IIC) in New Delhi.” I had never presented before a larger audience but I didn’t have the courage to say `No’ to her. So, I accepted that invitation and two months later I was at the IIC to present the lecture on Bhūta and Theyyam and the ritual performances of the west coast. The hall was packed.

While travelling to Delhi, I met George Fernandes on the plane. He said, “Come tomorrow to my place for dinner”; but I said, “Tomorrow I am giving a lecture at IIC. Perhaps you may like come and attend my lecture after which I would be happy to go to your place.” He came there along with Devaraj Urs and Madhu Limaye. As I came down from the podium after the lecture, Kapila Vatsyayan came and hugged me and said, “Fantastic, fantastic”, and asked me to see her at her office the next day. She was the joint secretary of the Ministry of Education and Culture. When I went to her office the next day, she gave me an application form to fill for the Senior Fellowship. In that form I had to give two references, so I asked her, “What shall I write?” She said, “Write my name”. And asked me to leave the second name blank. That is how I got the Senior Fellowship.

Another important thing happened when I gave the lecture at IIC in Delhi. There was Dr. V.K. Narayana Menon, who was the director of the National Center for Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai, in the audience. He asked me to present the same lecture in NCPA. I agreed and gave a lecture there as well. Sunil Kothari, who was in the audience, wrote a half-page article in the Times of India newspaper the next day. After the lecture, Dr. Narayan Menon came to the stage and gave me a bouquet of flowers and asked me to give him the papers. He was editing the Marg magazine, and my lecture was published in it. Recently, on the 75th anniversary of the Marg magazine, they selected the most prominent articles in those 75 years and my article was one among them. It is a great honour.

In 1981 I got a national award of Lalit Kala Akademi for my sculpture.

It seems that your career as a nationally recognized artist really took off from there.

BN: Yes. In the year 1981, I got an invitation from the Kashmir government for an artists’ camp in Srinagar. When I went there, there were about 20 people from all over India. One person who came there in a police vehicle approached me and introduced himself that he was present at the IIC when I had presented my lecture. During the conversation he said that Dr. Karan Singh was in Srinagar, and that if wished he could arrange a meeting with him at this place. The police officer came two days later to pick me up to meet Dr. Karan Singh. During the conversation, he told me that he was in the audience when I gave the lecture at the IIC. He suggested that I must apply for the Nehru Fellowship. Eventually I got the Nehru fellowship in 1982. I was only 45 then and was one of the youngest persons to get this fellowship. Even today, I am the only artist from South India to have received the Nehru Fellowship. I was doing a lot of field work at that time and this fellowship afforded me to carry out all that.

During that period, I saw full-night performances of Theyyam and Bhūta more than 50 times during the festival season. In 1983, I witnessed over sixty performances between December and April. That was really a wonderful experience. Once I saw it for eight nights continuously. Ebrahim Alkazi, the founder of National School of Drama, came with me to see this. And there were many other VIPs who came with me. At that particular point of time every Theyyam performer knew me. The best comment I have ever received during my academic research was from a Tantri, a Theyyam functionary belonging to the most famous Tantri family near Payyannur. He went and told the performer, “Balan Nambiar is watching. Don’t make any mistakes.” Because of a certain chronology to be followed in that ritual, they use nine betel leaves in a three-by-three matrix formation, and put a betel nut on each one of them, followed by a few more things. I was closely watching what they were doing, and at that time I overheard one of them making this comment in a hush. I was so serious about it that I could tell even if they made a slight deviation on the line.

The problem with the rituals is that the system may differ from one side of the river to the other. For example, Rakta Cāmuṇḍī of Theyyam, has different facial makeups on two sides of the river, north of Payangadi, about 14 km apart. Every facial makeup has a name and I have collected 46 such designs and their respective names.

We would now like to talk about your sculptures. You first started with clay, then moved to, perhaps mild steel, stainless steel, bronze and other materials. You must have also done wood and enamel. So the kind of tools that you use, we presume, would be different, and you need different kinds of skills. How did you learn the skills of working with different materials?

BN: Yes, the proficiency of handling different mediums is important. Clay is the most important medium for a sculpture student. This I learnt while a student at the College of Fine Arts. I was fortunate that when I joined the fine arts college, I knew the teachers there for six years already. They had become my friends. Except for three senior teachers, the remaining were good friends of mine. I used to call them by their first name. When I joined the college also the same camaraderie continued. In fact, I was also helping them send their parcels to places while I was in the Railways.

However, there were some conflicts with one of the teachers. It was during the second year when I was doing a sculpture. He said that a second-year student is allowed to do only a two-foot high sculpture. Since I was aware that there was no such rule, I asked for it to be given in writing. Then he got the letter signed by the principal, and posted it on the notice board, which stated that the height of the clay sculpture made by second-year students should not exceed two feet in height. So my next sculpture was two feet high, but five feet long. Seeing this, the teacher was really shocked. As I wanted to avoid conflict, I told him that I would buy the clay on my expenditure, and I bought a bullock cart load of clay and gave it to the sculpture department.

While you’re talking about measurements, I have a subsequent question. In ancient times, during the Śulba-sūtra period, I suppose strings, meaning ropes or threads, were used for markings and alignments. Even in modern day civil constructions, at least in India, they use ropes for these purposes. What do you use for measurement?

BN: In Kerala, there is an entirely different measurement method unlike our inches or centimetres. They take an ‘angulam’ or `kol’ as basic units, which is different for different people, but that is still a measurement.

In 1975, long before I met Dr. Raja Ramanna, I attended the Agnicayana function in a village called Panjal in Kerala. It was arranged by Frits Staal. The photographer Mankata Ravi Varma who made the documentary of that function was my friend. He told me that if I go there I could have a closer view of the rituals. So I was sitting with him in the inner circle of the function. What I was fascinated by was the involvement of mathematics in the altar! It is based on the measurement of the Yajamāna. The height of the Śyenaciti altar is based on the overall height of the Yajamāna from the floor to the tip of the finger stretched to the sky. That is divided by a certain proportion as the altar has five layers of bricks. So there is a human touch in all these, and they are calculated.

Yes, measurement is one thing, but for the actual construction you have to use different kinds of tools or mechanisms. I have always been fascinated observing building construction, the ease and efficiency with which they use the tube level, a certain pendulum-like device to set the walls at right angles from the ground and so on. They use strings, and I was reminded that in Śulba-sūtra there is a mention of rajju, meaning a ‘string’. So, in a sense, the tradition of actual construction seems to have passed on somehow.

BN: Yes, this knowledge is vast and is not written down. It is passed on from one generation to the next.

You just mentioned Raja Ramanna, who invited you to NIAS to make a logo for them, and you designed the logo for the institute. You suggested Śyenaciti from Śulba-sūtra. Could you recall what made you make that choice?

BN: We had a long talk. I was fascinated by our long heritage, that we already have this knowledge from around 800-600 BC or more when the Śulba-sūtra texts were written. There is a reference to this mathematics and symbolism. And I had been studying the symbol of altars as mentioned in the Soundaryalahari4. I felt that a logo should be easily adopted to different reproductions, on a letterhead for example. A line is more effective than a shade. So it struck me immediately, and within one week I made a small note and gave it to Raja Ramanna. They had a board of governors meeting for which J.J. Bhabha was the chairman. He knew me since he had bought my sculpture for the NCPA. He said, “You know, this is what we want.”

I want to make one thing very clear here. The logo is not my creative work, and I am only responsible for selecting it for NIAS. There was no second choice as I had given them only one. And they agreed to it. Much later when Frits Staal came to NIAS, he was very happy to see that I suggested this logo.5

In the 1975 function in Kerala that I mentioned, baked bricks were used for the construction of the altar. Though the actual Vedic ritual is a 12-day festival, it involves an elaborate preparation of nearly three months.

The logo is very symbolic indeed. You have symbolized the famous statement of Archimedes, `Give me a place to stand and I will lift the Earth’ in a granite sculpture.

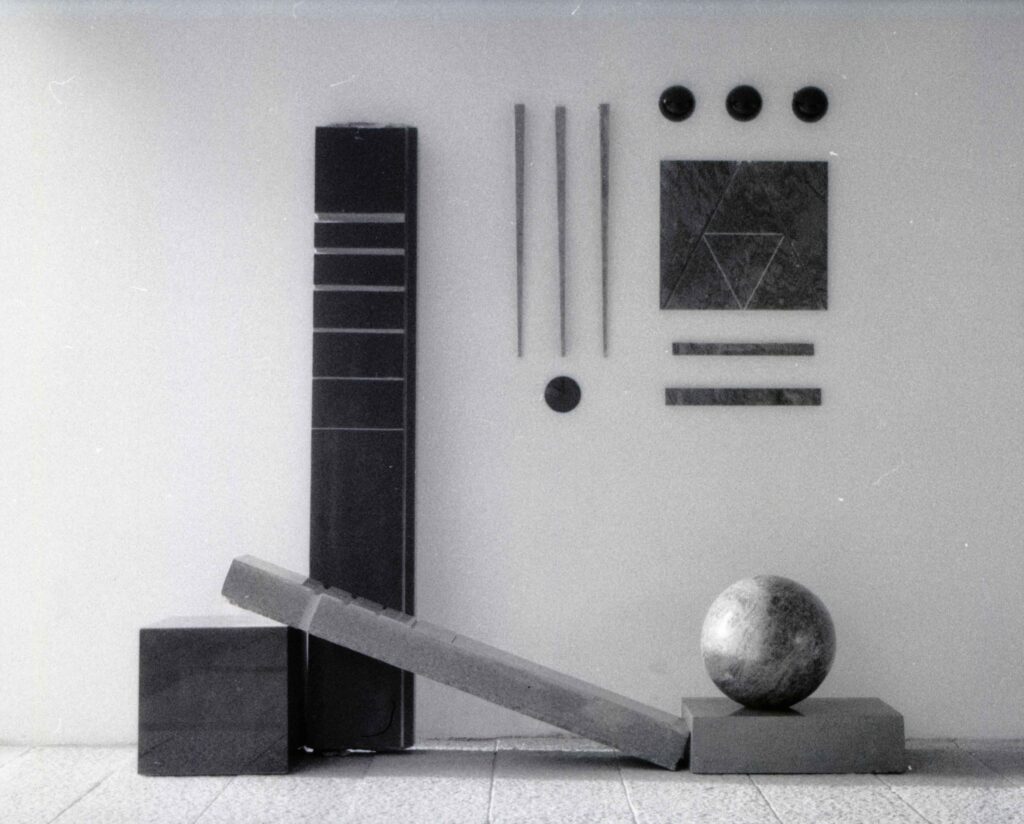

BN: Exactly, you see this is the difference between a layman and a scientist who can immediately see it (laughs). It is a granite sculptural composition at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Research (JNCASR). It was installed there one night before the opening of the Institution.

Now we want to ask about two of your sculptures, at least two. One of them is the Valampiri Shankha, or the right-handed conch and the other one is Sri Chakra. How did they come about? Were you commissioned to do them?

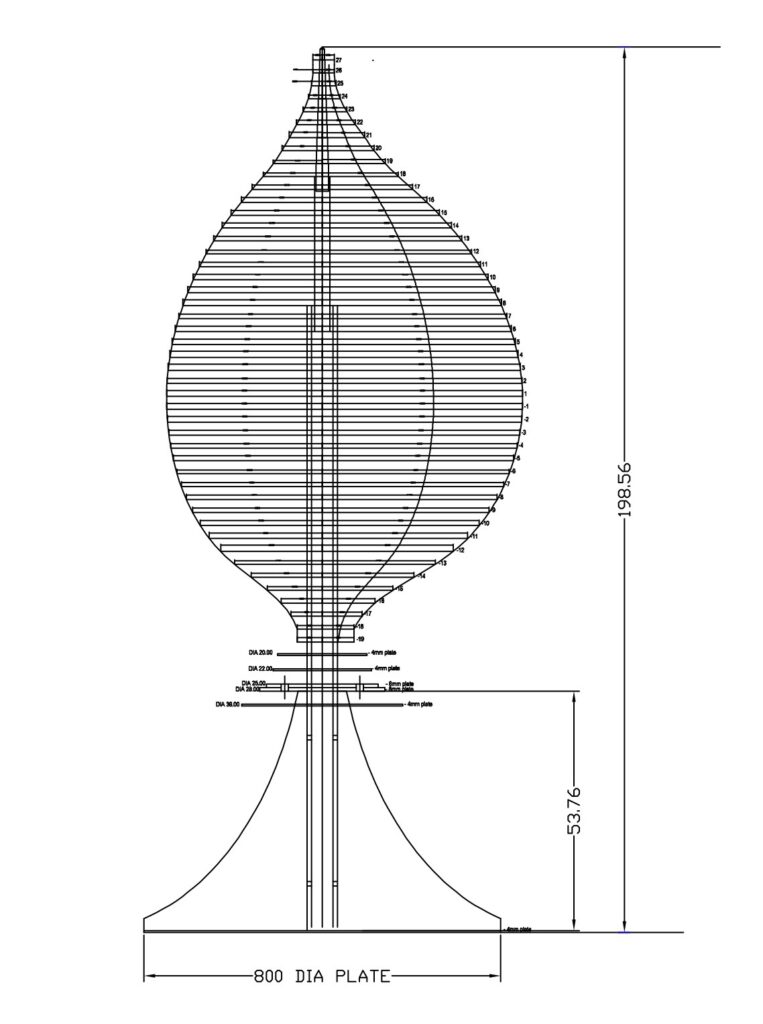

BN: In 1978, I had made a Valampiri Shankha,6 sculpture in glass fibre reinforced cement (GRC) in Heidelberg in Germany, and I was already aware of this golden ratio and the conch. I had also written about it. Then I did it in glass-fibre reinforced cement and was exploring the possibility of doing that in a more durable material, in metal, preferably in stainless steel. The cost factor of mild steel to stainless steel is 1:7. This is just the material cost. So, I needed a sponsor.

Fortunately, it so happened that this Texas Instruments R&D department director came to me and said that he would like to have a sculpture depicting DSP (digital signal processing). Texas Instruments was the pioneer in bringing DSP technology to India in 1986. The idea was to get a new material for the sculpture. I explained to him, and he wanted to see my finished sculptures. I took him to the JNCASR where three of my sculptures were installed. As we were coming out, he halted before the gate and said, “We would like you to do a sculpture depicting DSP for Texas Instruments.”

In DSP, a sound is converted into digital form, transported to another end, and is reconverted into sound there. So, there is some passage in which this magic is happening. Since DSP is about the transformation of sound, I thought that a conch would be the appropriate sculpture. And I briefly explained to the director that this is what I can do. The result was Valampiri Shankha.

The sponsor is generally welcome to see the progress of the work. Normally, I asked for 40% of the cost as first instalment and another 40% when the work is more than half way through, and remaining 20% of the amount on completion and installation of the work. They agreed. When I needed a second instalment, I asked them to come and see the progress of the sculpture. He said, “No. Make us a surprise. I will send you the cheque.” So, I made the sculpture. The size of the conch is 80 cm wide and 129.44 cm high, which is approximately the proportion of a golden mean, i.e., 1:1.618. He didn’t even come to see it during the installation. So I wrote a note and they made a poster.

Of all that you have accomplished so far, which art form has been your mainstay?

BN: I can’t identify one thing. It can be painting, it can be sketching, it can be drawing, it can be sculpture, it can be a different medium like the presently ongoing engagement with enamel. So, broadly speaking, art has been my mainstay. I get fascinated by it. Art has kept me active!

I am fond of music and literature, and I have a good habit of reading as well. I also like writing, but I must honestly admit that it takes more time for me to write a paper than to make a couple of sculptures. It takes me about a month or so to write a 20-page article, whereas I would have done many drawings and sculptures in the same time. That’s why my writing is very less.

What is your message for the modern-day artists, or art students?

BN: One thing I am worried or concerned about is that the junior artists seek premature publicity. That really is disturbing.

You are absolutely right about premature publicity. It can have adverse effects of killing the creativity in an artist because the initial curiosity quotient is bound to fade quickly. On a different note, in your photographs, in your paintings, enamel art works and sculptures, what one can discern is a common theme of symbolism. Anyone who sees your sculptures and paintings could say that they are from the same artist.

BN: Yes, that is there. But that is not a conscious effort. It is a spontaneous thing. It is like symbolism at various stages and in different ways.

Generally, mathematics is associated with numbers, the facility with computing, and counting. But the mathematical aspect in nature, in the sense that the geometry, the proportion and the measurements, are displayed in their visual appeal. Wherever you see something that is beautiful, a certain mathematical sentiment seems implicit. A leaf, a flower, or a fruit gives an unique identity to a plant or tree. Could one say that, in a sense, you capture the essence in your works?

BN: Yes, that’s really true. We can really interact or respond to a particular problem through symbols.

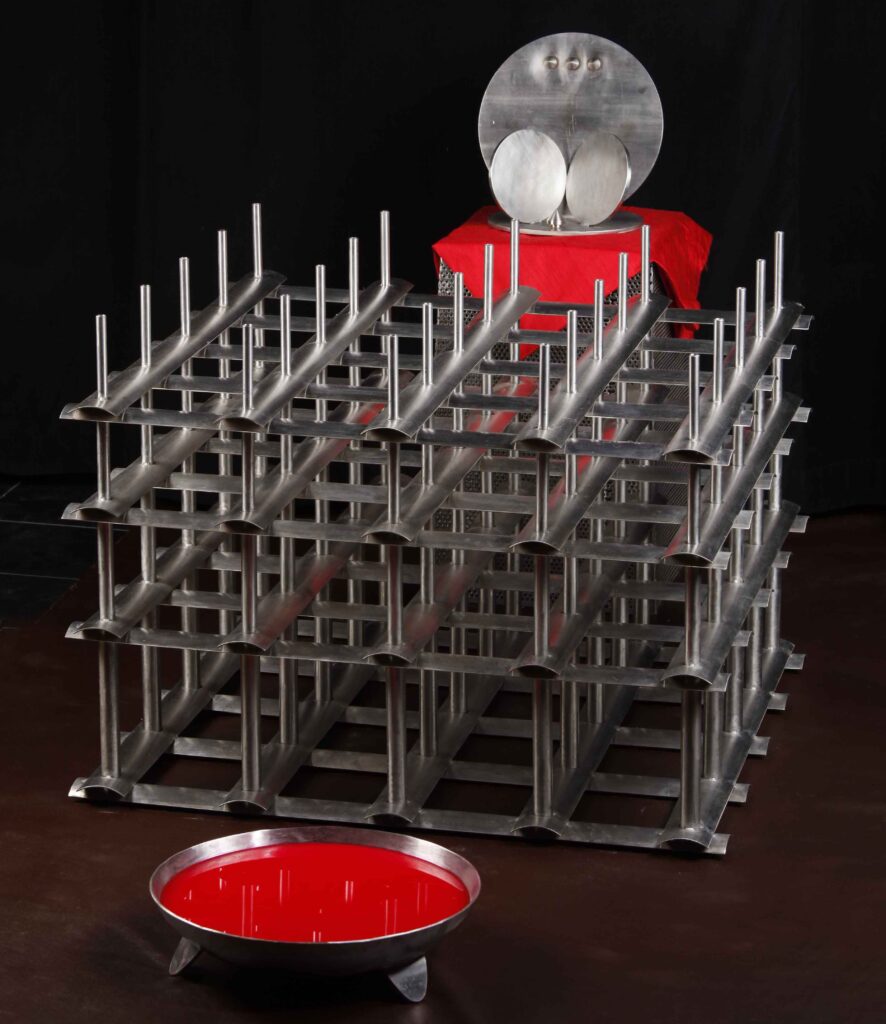

One of your stainless-steel sculptures reflecting on a Theyyam ritual, lighting an arrangement of wicks, immediately strikes a mathematics student as a 5 \times 5 matrix.

BN: The number of lighted wicks in an altar called “Kalasa-thara” varies. Single lighted wick to 64 lighted wicks are seen in Theyyam ritual functions. 1, 3, 9, 16, 36 and 64 are the numbers of lighted wicks used on specific occasions. Another objective of these ritual performances is the involvement of altars. In Theyyam, different altars can be seen. There are two types of altars: the improvised altars are one, and the permanent altars made of stone or masonry structures are the other. They are placed in such a way that appear seemingly erratic, but not so in practice. There is a specific reason for why it is erected in a particular spot and facing a particular direction. And that really is fascinating. I employed such motifs in my work.

One example is in the Saptamātrika art work, which is a stainless steel sculpture. These are all influenced by the altars in the worshipping places. In Kerala, images of Saptamātrikas are found in all Shakteya temples, either in iconographic forms or symbolic motifs in stone, stucco, wood or bronze at the southern courtyard of the sanctum sanctorum. Elsewhere they are also seen as bas relief, for example in the Lepakshi temple in Andhra.

Your stainless steel sculptures titled Celebration of asymmetry and Asymmetric form seem to have a certain mathematical connotation to them. We would like to hear about the genesis of these sculptures. Could you please recount how they came about? Were they part of any scientific event or institution?

BN: Most of my earlier sculptures in mild steel were in symmetrical compositions. Keeping the vertical format in some compositions, I thought of doing a series of sculptures in stainless steel both in symmetrical and asymmetrical formats. It was done with conscious effort. I have often used the golden ratio proportion or the Fibonacci numbers in my sculptures.

Similarly, the two sculptures titled Unending loop, are also objects that have undergone an intense mathematical exploration under a topic called Knot theory. How did these sculptures come about?

BN: Frankly I have not heard of knot theory. I first did a sculpture of a “Knot” inspired by the darbha-grass knot used on the occasion of a death ceremony. I manipulated the darbha-grass knot to make a sculpture composition. This 2.6metre-high sculpture in stainless steel was done in 2003, and was acquired by the Ministry of Defence, Government of India in 2005 from my solo exhibition of stainless steel sculptures at the Art Heritage in New Delhi.

Later, inspired by snake motifs such as Nāgamaṇḍalas and various intricate stone bas-reliefs, I made a series of sculptures such as unending loops. I have collected over hundred diagrams of snake motifs, drawn on the floor in multiple colours in various sizes, for conducting pujas. Though these diagrams are two-dimensional, I, as a sculptor, have created their three-dimensional formats inspired by them.

I would like to come back to the NIAS logo. The 1975 experience you recall is an elaborate construction. You had mentioned that the size of the brick is determined by some measure related to the height of the Yajamāna. As a humorous take on that, I wanted to say the following: In your enamel work, you mentioned that you designed your oven here from that of your father-in-law, and you took his model and did it; but you also said that the height is a little low because he was short, and you have to bend a bit to use it.

BN: Firstly, the overall height of the Yajamāna of the “Athiratram” festival determine the measurements of the Yāgaśālā as well as the size of the bricks of the Altar.

The oven I am presently using at my enamel studio in Bangalore was fabricated in Peenya by a private fabrication unit under my supervision. Some components were fabricated at my basement workshop. The oven design is based on the oven at the enamel studio of my father-in-law Paolo De Poli in Padova in Italy.

Can you recount your internship days with your father-in-law, in his studio?

BN: My father-in-law was very secretive about the technique of enamelling. It took seven years for me to enter his studio. But when he realized that I am not imitating him, he started helping me. In my absence he would go and see my work, and if he liked something, he would put a yellow sticker on the work and telephone my wife and say, “Balan has done an excellent work, a masterpiece. Ask him not to sell, but keep it for the family”. He became very generous. Three to four years later, one day, it was very emotional for me as he took all the keys of his studio and gave them in my hand and said, “Hereafter, you look after the studio”. Since then I must have done over 200 enamel paintings.

Jewellery enamel is glass powder, and silica sand is the main ingredient. Metallic oxide or mineral oxide gives the colour or the pigmentation. Gold, silver and copper are metal surfaces on which enamel art works are done. European goldsmiths who were invited by the Mughals brought the jewellery enamel colours to India to design the sword handle, jewellery boxes, ornaments, and such articles and artefacts. The traditional jewellers of India used less than ten shades of colours. India never produced jewellery enamel colours. I have been using over 250 shades of enamel colours in my creative works on silver and copper. Among all the coloured creative mediums in history, enamel works are the most durable, and absolutely permanent.

How did you and your wife Evelina happen to meet each other?

BN: As a guest of the German Government I was in Munich, visiting museums. It so happened that the two of us would spend almost the same time, at the same paintings. Thus started a conversation when I asked her, “Do you know English?”, and as we exchanged our views we saw that we resonated on many things!

(To Evelina.) Your father was a celebrated enamel artist and he had a big studio in Italy, and you grew up seeing the artworks of your father. Then you are married to an artist, while you, yourself, are a nuclear physicist. What made you take to science?

Evelina: There was no clash because both possess a common desire for inquiry. Like my father, inspired by something you know, always tried with different materials; and science means, trying to understand why things work. I think they all go well together. I love numbers.

BN: When I presented a series of lectures on golden ratio, fibonacci numbers and fractals, Eva helped me extensively in identifying diagrams and organizing them.

In this long journey of your creative work, have you found any potential student who could be a torchbearer of your works?

BN: I have many students. None of them imitate me. And my methodology of teaching is also that I want them to develop their own identities. Many have taken to the professional art line. There are at least 40 people in architecture, sculpture, painting and design.

That’s a great accomplishment. You must be proud of this as well.

BN: You know my father-in-law used to quote [Leonardo] da Vinci very often in Italian, which translates as: “A good teacher is one who takes pride in the achievement of his students”. I liked that quotation. I have been conducting classes for children from 1971 onwards and I do not collect fees. There are many who were my students, who are now eminent artists themselves. I feel like a parent bird, seeing the kids strengthening their wings and soaring to the limits. I liked to impart the knowledge I gained and holding no commercial secrets of the trade. I liked to impart whatever I knew. You have to really expect that your student grows bigger than you. Picasso’s father was an art teacher. Picasso became great; greater than his father. And sometime in the future there may be an artist who may even become greater than Picasso. But you have to make that provision to the student and see where exactly their talents and limitations are. I like different fields, I do paintings, sculptures, enamel art, photography and so on. I do not see any limit to creativity. The worst enemy for creativity is pre-occupation.

The big stainless-steel sculptures you made must have involved help from many people. Is there anyone who is taking it forward?

BN: For large-scale sculptures in any place, one needs a lot of other external help and facilities. And for practical reasons, the cost of stainless steel production is seven times higher than normal steel. So if one wants to make a sculpture of stainless steel, say seven metres high, it’s a very big investment. It needs a sponsor. But the creative process is the same whether it is normal steel or stainless steel. I have always consulted the experts for structural stability. Most of the time they concur with what I prepare, but I get it verified and also certified by them.

As a last question, could you briefly tell us some of the prominent aspects of Theyyam, which has been a topic of your deep study and, by your own admission, has held your fascination right from childhood?

BN: There are hundreds of Theyyam performances. One of them is Kathivanur Viran, a hero who fights valiantly with his enemies and dies. On hearing the news his wife Chemmarathi takes up arms, fights with the enemy and becomes victorious. She jumps into the funeral pyre of her husband and becomes a Sati. People see a blue flame coming out of the pyre ashes and realize that there is some divinity at play, and make an altar in the name of the hero’s wife. This altar called “Chemmarathi-thara” represents the spirit of the wife. These are legends alright, the blue flame coming out of the pyre, a star seen in the sky during midday are all fantasies. But, for me, from an artistic point of view, these inspired me to come up with a creative work titled Altar.

For instance, I made a metal mirror of mother Bhagavati symbolically, using red liquid, red flowers, and red cloth. Mirror images are there in almost all Theyyam shrines in northern Kerala. There are no idols except Varāhi in Kerala, or the [Bhūta] Panjurli in Karnataka. Shivarama Karanth7 and I had correspondence on this. His theory, to which I agree, was that in very early society, spirits of five animals were worshipped by villagers. They are the tiger, bison, elephant, wild boar, and snake. And he says that these were the wild animals that villagers were afraid of; and, in time, the spirits of these animals were deified by these villagers. Much later the legends and myths became attached to this. An artist may symbolically employ these myths and legends, as they provide very fascinating imagery. There is unlimited scope for fantasy.

I simply say to myself in silence: May God bless me to do good things!

Perhaps it also represents a conflict between humans and animals?

BN: There is a conflict but there is also a beautiful understanding of primitive society. They don’t kill animals in mating season, and when they give birth to younger ones. There are certain seasons when they will not go into the forest. There is a demarcated area called “devara kaadu” (divine forest), where they will not tread. At the entrance of a divine forest, there may be a shrine. In the shrine there may be an idol. If there is no idol, they may keep a symbol of weapons and so on. So, when I look at them as an artist, there are so many things that can be depicted artistically. When these are depicted with a visual impact, you know, they may become beautiful art works.

As far as my involvement goes, I go to this place and observe their ritual. If a Theyyam comes and gives me prasādam or something like that, I respect that occasion at that instant, and will stand up from the chair to receive the blessings. If they ask me to pray, I simply say to myself in silence: May God bless me to do good things!

It was absolutely fascinating! Symbolically capturing the tradition via a ritual kind of conveys a sentiment that cannot be captured in thousand words. Thank you so much! \blacksquare

Footnotes

- One can read a detailed write-up on NIAS logo by Roddam Narasimha here: when he was invited to design one by the then director Raja Ramanna.↩

- Polytechnic is a diploma or vocational course in which an institute focuses on delivering technical education. ↩

- Official residence of the governor of state. ↩

- A poetic work from the eighth century CE by Adi Śankara. ↩

- One can watch a talk by Balan (from 46:30 onwards) on this NIAS logo here: ↩

- It is a right-handed conch shell – Turbinella pyrum – with a clockwise spiral; The spiral of the conch is equiangular. Its spiral can be determined either by analytical methods or by elementary geometry. The vector angles about the pole are proportional to the logarithms of the successive radii. That is why the spiral of the conch is often referred to as a logarithmic spiral, a geometrical spiral or a proportional spiral. ↩

- Shivaram Karanth (10 October 1902 – 9 December 1997), was an Indian polymath, who was a novelist in Kannada language, playwright and an ecological conservationist. He was honoured with the Jnanpith Award in 1978 for his contribution to Kannada Literature. ↩