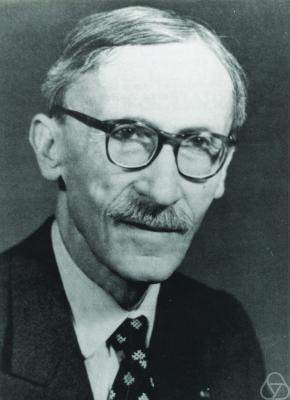

The romantic poet Keats (1795–1821) compared human life to a large mansion of many apartments, only two of which he could describe, the doors of the rest being as yet shut upon him. Laurent Schwartz’s autobiography, written at the age of eighty-two, has just appeared and describes more than two apartments, not romantically but in limpid prose. Its gripping interest derives from the richness of events that have filled his career—as a creative mathematician of the first rank, an educationalist of renown, and a political activist grappling with the burning issues of his time—and from the searching honesty and lack of egotism in their description. Some of those events are so painful as to have daunted any lesser spirit. With remarkable courage, Schwartz is willing to look at his earlier selves, and look at them hard. He has the generosity to show in his book his true self, with its humane impulses and moral commitment. His analytical mind is subtle and penetrating, and he articulates his thoughts on mathematics or music, Beethoven or butterflies, Mahatma Gandhi or Ho Chi Minh, Bertrand Russell or Jean Paul Sartre, communism or colonialism, the persecution of Jews or the repression of dissidents with such clarity and with such well-balanced reasoning that one is inevitably reminded of the writings of Gandhi in Young India (who called his autobiography My Experiments with Truth).

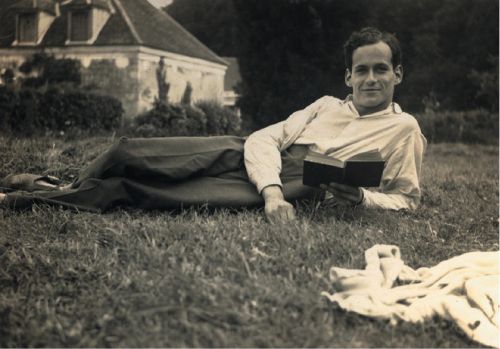

The book opens with a description of the country home at Autouillet (40 kilometres from Paris), which his father acquired in 1926 when he was just eleven and his brothers Bertrand and Daniel were just nine and seven. His father was a famous surgeon in Paris who helped him overcome the poliomyelitis which he had contracted the same year, and his mother’s love of nature, which was transmitted to all her children, found its fulfilment at Autouillet. It is the anchorage of Schwartz’s childhood memories, his Garden of Eden. He recalls its sights and sounds with an unassumed tenderness: the fruit trees (especially the figs), the flower beds, the herb garden, the fishing pond, the French lawns, the birds and insects and their behaviour patterns. He seems to lend support to George Orwell’s observation that “by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies, and toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable,” and that “life is frequently more worth living because of a blackbird’s song, a yellow elm tree in October, or some other natural phenomenon.” It is in the shade of a giant chestnut tree at Autouillet, within earshot of birdsong, that many of his manuscripts took shape. His fascination with butterflies, which evolved into a lifelong hobby, began when he was barely five and became serious at Autouillet, which was the centre of reunion of family and friends. To the young and intellectually acute but physically fragile Schwartz, Autouillet offered the joy and happiness of Paradise. No doubt that experience helped to sustain his spirit in the difficult and painful years that lay ahead.

At school Schwartz excelled in Latin and Greek and mathematics. Thanks to the advice proffered to his mother by a discerning professor of literature (Thoridenet) and by his uncle (mother’s brother) Robert Debré, mathematics was the course he finally followed, which in retrospect seems entirely justified. Preparing to enter the École Normale Supérieure (ENS), admission to which is by competitive examination, he fell in love with his schoolmate Marie-Hélène Lévy, daughter of the famous mathematician Paul Lévy (who was then a professor at the École Polytechnique). They became engaged in April 1935, when both of them were at the ENS, and intended to get married in December 1935. But in October that year she contracted a pulmonary tubercular infection and had to move to a sanatorium (at Passy, in Haut Savoie). Eighteen excruciating months of separation followed, during which they stayed in touch by correspondence. Schwartz’s unswerving devotion to her during that period showed his mettle. (They got married in May 1938. They have had two children: Marc André, a poet and writer, who passed away suddenly in 1971; and Claudine, married to Raoul Robert, both of them professors of mathematics now at Grenoble. Marie-Hélène herself, overcoming all obstacles, wrote her doctoral thesis in 1953 and accepted a professorship at Lille in 1963.) Schwartz observes drily: “We have not even celebrated our silver wedding in 1963, or our golden wedding in 1988.” Marie-Hélène, according to Schwartz, has the seeing eye for geometry, which he himself lacks, even though projective geometry was his first love. Her mathematical vision complemented his, and her strength of character reinforced his. His interests turned to analysis and probability. His great uncle Jacques Hadamard was a great inspiration, also Paul Lévy. Both of them lived to see his own work on distributions crowned with the award of a Fields Medal in 1950.

The years spent at the ENS were not only decisive for his mathematical career (as well as his wife’s) but also for his political involvement. By instinct an internationalist and anti-colonialist, his deep and extensive study of economic geography and political literature led him to the conviction that the policy of “nonintervention” (1936–38) practised in France by Leon Blum’s government in the face of Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, Stalin’s purges, and the Spanish civil war was totally ineffective, if not extremely dangerous, and that the benefits of colonialism were far outweighed by the exploitation of peoples. He decided to seek some answer in Trotskyist theory. It took him a while (1931–47) to conclude that Trotskyism was divorced from reality, and he has remained independent of any political party ever since (except for a few years in the sixties when he belonged to the PSU, Parti Socialiste Unifié, as a secondary activity). The chapter on his years as a Trotskyist, written with the advantage of hindsight, goes to the heart of his political credo—his nonviolent approach, his moral commitment, his resolute will to oppose oppression, his desire to serve humanity, above all his intellectual honesty. (Aung San Suu Kyi, asked recently what “political integrity” meant to her, replied, “Just plain honesty in politics.”) Gandhi would have welcomed his affirmation that “the end not only does not justify the means, but the means are an intrinsic part of the end, which they ineluctably influence.”

Soon after leaving the ENS, with an excellent record, Schwartz decided to do his (obligatory) military service of two years (1937–39) as an officer, followed by a third year of active service (1939–40) during the war; thereafter he remained an officer in the reserves. His lecturing skill, later to become legendary, was already in evidence during the service and helped him avert getting into scrapes; so was his capacity for decision making. These years witnessed the unrelenting march of tragic events: the annexation of Austria (1938), the Munich pact (30 September 1938), the occupation of Czechoslovakia (March 1939), the Nazi-Soviet pact (August 1939), the victory of Franco in Spain (1939), the German (and Soviet) invasion of Poland leading to World War II (September 1939). Following France’s defeat by the Germans, Vichy became (July 1940) the seat of government of the capitulationist French regime headed by Marshal Petain, which administered the southern, unoccupied half of France. Demobilised in August 1940, Schwartz went to Toulouse, where his parents were staying. His father, who was a reserve colonel in the medical service, was working, on a voluntary basis, as a surgeon in a hospital. Schwartz applied for, and obtained, a membership in the Caisse National des Sciences (the future CNRS) till the end of 1942. A stipend from the ARS (Aid à la Recherche Scientifique), founded by Michelin, kept him going from 1943 until the end of the war. Chance intervened to rescue him from the scientific desert in Toulouse in which he found himself. Henri Cartan happened to go to Toulouse to conduct the orals for admission to the ENS. Marie-Hélène, who was in need of advice about how to resume her work (after a three-year interruption, 1935–38), took the initiative to meet Cartan, who advised them strongly to move to the University of Clermont-Ferrand, which had a faculty of its own, combined with that of the University of Strasbourg, which had been withdrawn (from Strasbourg) and posted there. The change proved highly beneficial. It was at Clermont that Schwartz had his first encounter with André Weil and (the mathematical collective) Bourbaki, stimulating enough to let him finish his doctoral thesis in two years (by January 1943, with the translated title Real Exponential Sums).

While his research progressed, the flames of war spread worldwide and brought new dangers ever closer. Hitler failed to subdue Britain with his air attacks on London (September 1940) and invaded the Soviet Union (June 1941). Japan declared war against the U.S. and U.K. (December 1941). The Germans occupied the whole of France (November 1942). His physical frailty precluded Schwartz from joining the Resistance movement. He risked deportation as a Trotskyist; being of Jewish origin (though an avowed atheist) added to the peril. In March 1943 Marie-Hélène gave birth to a son, Marc-André, and the young family was in multiple jeopardy. The ineffectiveness of the Trotskyist party filled him with frustration: “Trotskyism gave me, during my years at the ENS, a remarkable education, clearly more advanced and sophisticated than that of most youngsters of my age. But by the extremism and sectarianism of its ideas, and by its stereotyped language, it neutralised me during the occupation.” Some in the Trotskyist party were engaged in converting German soldiers into anti-Nazis, even Trotskyites. Most of them were arrested and deported. “My judgment remains extremely severe on my own actions as well as those of the majority of the Trotskyist party during that period.”

It was not just a question of personal frustration, but one of life and death. Two of his contemporaries working for their doctorates at Clermont were Feldbau, a student of Ehresmann, and Gorny, a Polish refugee working with Mandelbrojt. Feldbau was deported to Auschwitz (November 1943), and Gorny to Drancy, never to reappear. A leading article from the Times of London (3 November 1997) recalls: “From Drancy 76,000 Jews were deported between 1942 and 1944, rounded up by the French police acting on the orders of the Vichy government. At the war’s end, 2,600 returned. Many more French, including clergy, sheltered Jews than did so in other Nazi-occupied countries.” The crimes of the Nazis and of the Vichy regime became palpable realities. Deportations and disappearances increased even as military defeat stared them in the face (Stalingrad, February 1943; North Africa). The extermination of European Jewry seemed to have become Hitler’s principal aim; that of the Allies was his destruction. They never allowed themselves to be preoccupied by what now seems to be the genocide that was being perpetrated (and they are still undergoing atonement). Schwartz always entertained the idea that it would be very useful to create a Jewish army, partly recruited in Israel, with a massive stock of weapons, to show the German soldiers what it would be like to fight against a race that they misrepresented as inferior and submissive, which could have tipped the balance psychologically. But he well knew that a good many geopolitical reasons operated against the idea. It becomes clear in retrospect that the Allies could have acted to halt the deportations, at the minimum, but failed to do so. How he had to adopt a false identity (Laurent-Marie Séli-martin, a high society Protestant name, instead of Laurent-Moïse Schwartz, and Marie-Hélène Lengé) and cover his tracks well enough to escape detection seems now like the stuff of fiction, but the anguish and the danger present at the time could have broken the spirit of any person who did not have the clear-headedness, courage, and presence of mind that Schwartz possessed, and the sheer luck that came his way. His good humour, adaptability, and his capacity to welcome with a smile the smaller pleasures of life kept him sane and relatively safe, with some hairbreadth escapes, near St. Pierre-de-Paladru, a little hamlet north of Grenoble (in the Italian occupied zone). He plainly and tellingly describes the texture of his daily life during those years of personal peril: the rooms one lived in, the food one ate, often with an air of detachment, as if one was describing someone else. Celebrities appear, but it is the vignettes of the uncelebrated (like Mme. Martha Carus, the restauratrice at Paladru) which stick in the memory. (She is now eighty-eight, and her daughter, who once got a few piano lessons from Schwartz, is now a professor of music). It is the ordinary occurrences of life where the distinctive features of character and psychology emerge most clearly that catch attention. A police superintendent who questioned Marie-Hélène about their suspected contacts with Trotskyists concludes with the comment: “You Alsatians, you are like us Corsicans, we are patriots.”

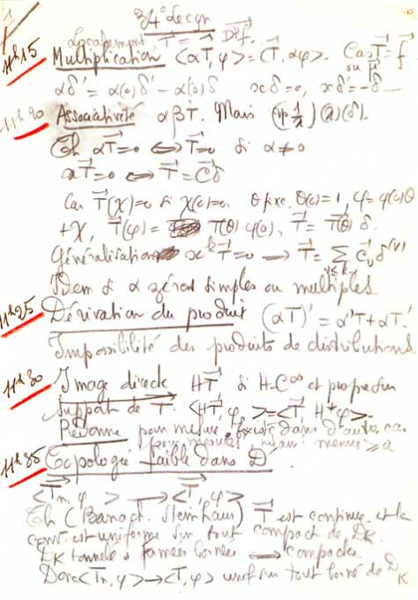

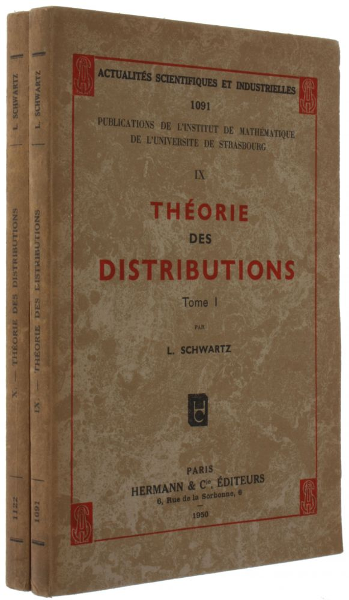

It is an extraordinary instance of cerebral percolation that, after such a trying period entirely taken up with problems of survival rather than mathematics, Schwartz should have come up with his idea of distributions (in 1944–45, just as the war was ending and normality returning, while still carrying his false identity), which, in one go, cleared up the mystery of the Heaviside “function” (1893), renamed Dirac’s “delta function” (1926), and opened the way to the theory of Fourier transforms of (tempered) distributions, which has proved so fruitful in the study of partial differential equations, exemplified by his own work, that of his distinguished pupils, and notably that of Lars Hörmander (Fields Medal, 1962). Schwartz’s idea has all the simplicity and inevitableness one associates with work of the highest class. His chapter on the “Invention of Distributions” is an example of his extraordinary skill in the presentation of mathematics; it is also a model of fair-mindedness in its coverage of the work of his predecessors, contemporaries, and students. Particularly touching is his reference to Georges de Rham and his theory of “currents” (p. 240). According to the citation for his Fields Medal, Schwartz has “clearly seen, and been able to shape, the new ideas in their purity and generality,” adapted to the needs of further research. Bourbaki’s influence on the process of percolation clearly is a moot point. Scattered throughout are his remarks, with concrete examples, on the nature of research, its joys and sorrows, its zigzag turns and deviations, the partial successes followed by the sudden illuminations. If cast on a desert island, Schwartz would like not only to do research but to teach. After a one-year appointment in Grenoble (fall 1944), Schwartz joined the Faculty of Science at Nancy (fall 1945), on the initiative of Delsarte and Dieudonné, and stayed there for seven very fruitful years, fruitful both in research and teaching, attracting such brilliant students as B. Malgrange, J. L. Lions, F. Bruhat, and A. Grothendieck, who in their turn have enriched mathematics in unforeseen ways. Politics still had its claim on his time, as evidenced by his unsuccessful candidacy as a Trotskyist in the French legislative elections in 1945 from Grenoble and in 1946 from Nancy. But his mathematical achievement attracted international attention, beginning with Harald Bohr’s1 invitation for him to visit Copenhagen in October 1947 to give a series of lectures on his work. It was Bohr who was to present him with a Fields Medal three years later at the International Congress of Mathematicians at Harvard (1950). He was one of the four invited speakers (along with Dirac, Zygmund, and Bhabha) at the First Canadian Mathematical Congress (of a month’s duration) in Vancouver in 1949. Notes of his lectures in English received wide circulation. His two volumes entitled Théorie des distributions were published in 1950–51.

Although he bade goodbye to Trotskyism in 1947, it clung to him like a limpet when he was to go to Harvard (August 1950) to receive the Fields Medal. The Trotskyist party was listed as a “prohibited” organization by the U.S. Government, and members were precluded by law from entering the U.S. unless a waiver was granted by the U.S. State Department. In response to pressure from his hosts, a waiver was indeed granted at the last minute, though his movements within the U.S. were sought to be restricted. It was the time of the Korean War, with McCarthyism at its peak in the U.S. He went to Berkeley in 1960 for two months, again with a waiver. The denial of easy entry to the U.S. (until 1962–63, when he spent a sabbatical year at New York University) meant a gain to other countries anxious to have him, such as India, Brazil, Mexico. His visits to India gave an impetus of inestimable value to the development of mathematical research in that country and brought lasting benefit.

On Denjoy’s initiative he moved from Nancy to the Sorbonne in 1952, and in 1958 he became a professor at the École Polytechnique (EP) as well. With tremendous energy, clarity of vision, and skill in handling human relations, he brought about fundamental reforms in such a classic and staid institution as the EP by modernizing its programme for the training of engineers and by making it a flourishing centre of mathematical research in its broadest sense. His achievement was acknowledged by the French public and by successive French governments when he was appointed president of the National Committee for the Evaluation of French Universities (1985–89).

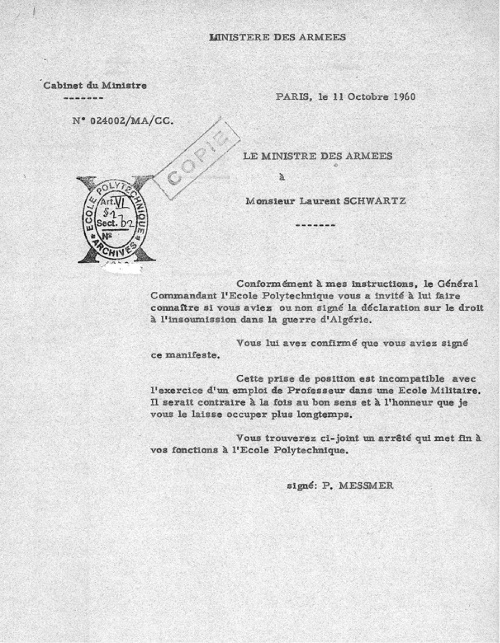

His rise to fame as a mathematician on the international stage and his thumping success as a reformer of the EP on the national stage did not by any means diminish his political commitment. As a confirmed anti-colonialist, he was a keen observer of political developments that led to the decolonisation of Vietnam (Geneva Agreement, 1954), Tunisia, and Morocco (1956), made possible by the statesmanship of Pierre Mendes-France. Algeria presented a special problem, because (around 1960) it had a French population of a million living alongside nine million Algerians. Schwartz was appalled by the cycle of terrorism and repression which developed there, and the widespread use of torture posed a challenge to his deeply held beliefs. While he sympathised with the goal of self-determination, he kept his distance from the nationalist movement. Matters came to a head in an unexpected fashion, and he was inexorably drawn into the political vortex. Maurice Audin, a graduate student from Algeria, who was to have completed his doctoral thesis in Paris under his supervision, was suddenly arrested (11 June 1957) in Algeria and disappeared. Audin was French, not a Muslim, but a communist. It turned out that he had been tortured and murdered at the hands of the forces of law and order (on 21 June). There was no official response to numerous inquiries. This cut Schwartz to the quick, outraged his sense of justice, and triggered his determination to galvanize public opinion against the practice of torture, and especially against the abuse of the special powers invoked by the government for the use of third-degree methods to put down the rebels in Algeria. Schwartz focussed on the case of Audin (as Gandhi did on the salt tax), founded the Audin Committee (fall 1957) to demand a clarification of the circumstances surrounding his death, arranged for the award of a doctor’s degree, in absentia, for Audin’s nearly, but not quite, complete thesis (December 1957), and wrote a famous article in L’Express on “the revolt of the universities” against the practice of torture by governments. His photograph appeared on the cover, and the article gained the attention and support of a wide public and made him a national political figure. Protests and demonstrations followed. The Algerian War became increasingly unpopular, especially after the failed Anglo-French military expedition to control the Suez canal and the Soviet occupation of Hungary. There was unrest among the youth who were subject to conscription. And in 1960 Schwartz was a signatory of the famous manifesto signed by 121 French intellectuals, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, which proclaimed solemnly the right of the French youth morally to rebel against the Algerian War. This resulted in his dismissal from his professorship at the EP by the defence minister. Schwartz went to the Administrative Tribunal to challenge the legality of the decision; the Tribunal did find it illegal, but on the technical ground that he had not been given the opportunity to see the file containing the grounds for action. The minister appealed, this time showed him the file, and repeated the dismissal. Schwartz went on appeal to the Council of State on the ground that the file had, in fact, been empty. While the case was pending, it proved difficult to find a successor, except on a stop-gap basis, for one year at a time, because of the solidarity of the professors in confronting the authorities on the question of academic freedom without political shackles. Schwartz left to spend the year 1962–63 in New York University. A compromise was reached out of court with the minister, according to which he would be reinstated if he reapplied for the post, which he did in 1963–64.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1961, bombings with plastic explosives organized by extreme right-wing elements began to take place near the apartments of those fighting against torture. Roger Godement’s apartment came under attack; so did Sartre’s, and Kastler’s, and several others; there was one in the garden opposite Schwartz’s fifth-floor apartment. Clearly present was also the threat of assassination; an armed policeman in mufti was assigned by the government for the protection of Schwartz’s family. Nevertheless, (in February 1962) his son, Marc-André, was kidnapped, held in a forest for two nights, and then released. Interested parties tried to make a mystery out of this tragic episode, but such machinations were countered in a famous article by Alfred Kastler in Le Monde in which he warned the public against being taken in. This horrible experience obviously took a heavy emotional toll of Marc-André, for even as he was recognized as a writer of talent for his novel L’Automne (1970), he developed a psychosis of suicide and ended his life (21 March 1971)—a terrible blow to his family and friends, who had always known him as a bright, alert, jolly child, with his collection of butterflies, his understanding of science, and his bent for poetry. The suicide of a son touches many hearts. The view of life expressed by Ted Hughes (now England’s Poet Laureate) in the context of (his wife) Sylvia Plath’s suicide (herself a poet) comes to mind: “Human beings have always been dwarfed by the elemental power-circuit of the universe.” During those troubled times the Schwartz Seminar at the university very kindly was conducted for a year by Bernard Malgrange. Nobody forgets a good teacher, they say. Even after the Evian Agreement (March 1962), which brought about a ceasefire in Algeria, Schwartz had occasion to protest against torture practised by those who took over power, and he is aghast at the political catastrophe now facing that country. But one cannot rewrite history.

Schwartz’s political activity reached a crescendo during the Vietnam War. The longest chapter of his autobiography deals with Vietnam’s struggle for independence and his own part in it, a worthy and honourable part, “more than a drop in the ocean.” He meticulously describes that struggle, beginning with the civil war between Vietnamese nationalists led by Ho Chi Minh (the “Viet Minh”) and the French, which ended with the Geneva Agreement (April–July 1954) concluded by Pierre Mendes-France. That Agreement provided for the recognition of North Vietnam (north of the 17th parallel) and South Vietnam, with free elections to be held, within two years, under the supervision of an International Control Commission (Canada, Poland, India), for a unified Vietnam. The Agreement was never fully implemented by the South, which was backed by the U.S. against the communist North. When military pressure from the North increased, the civilian regime in the South was ousted by a military coup (1963) backed by the U.S. On the excuse that the North Vietnamese had attacked the U.S. Navy, American Marines landed there, and the U.S. Air Force began bombing raids on North Vietnam. As the bombings reached ever new heights of ferocity, causing immense destruction and enormous suffering of the civilian population, Schwartz founded, along with Sartre, Kastler, Vidal-Naquet, and Bartoli, a National Committee for Vietnam (NCV) to rouse public opinion to protest against the undeclared, heinous war with its appalling brutalities (1966). Schwartz was also a member of the Russell Tribunal, which was set up by the Bertrand Russell Foundation to act as an international jury (without a judge) to hear and examine evidence of indiscriminate attacks against civilian targets, like churches, schools, hospitals, and dikes, and the effect of the use of napalm, defoliants, phosphorous and antipersonnel bombs on the civilian population, especially children. The Tribunal heard the evidence provided by observers whom it had sent to Vietnam for a first-hand investigation of the facts. The crucial question before the Tribunal was whether genocide had taken place in Vietnam, and its unanimous answer was yes. Schwartz says he is still bothered by that answer, though the assembled evidence was appalling. The work of the Tribunal received worldwide publicity, not necessarily always followed by approval.

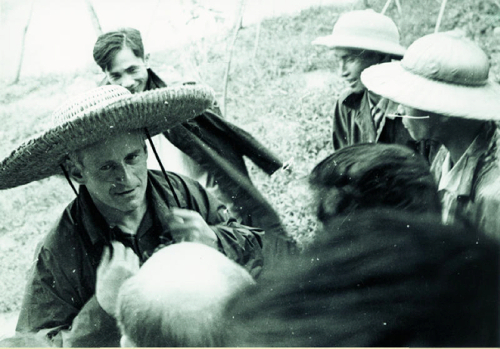

Soon after the sittings of the Russell Tribunal, Schwartz received an invitation to visit North Vietnam for three weeks. Towards the end of August 1968, he went to Hanoi via Pnom Penh (a few days after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia). “My window gave on to a lake, unveiling a part of Hanoi. Like some graceful shadows, beautiful Vietnamese girls in black silk dresses rode past on bicycles.” He had meetings with the prime minister, Pham Van Dong, lasting three hours, and talked also to Ho Chi Minh for about an hour (which, according to American diplomats, was rare). The message he got was that Vietnam would concentrate on winning the war and would make no concessions and that negotiations should be concerned only with the cessation of all bombing everywhere. Though few at home believed the message that he had brought back from Hanoi, events have vindicated Ho Chi Minh. Schwartz did not fail to convey to his hosts his disapproval of their nonobservance of the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war, since they never gave the names of prisoners, nor reported on their condition, nor allowed any access to them. Seemingly as a recompense, they arranged for him to meet and talk to an American pilot who had been shot down and taken prisoner. His family was pleased to get news of him from Schwartz. He says of his first visit: “That trip has left an indelible impression on me because of its diversity and intensity. I became forever closely linked to Vietnam. I have since returned there several times, but for purely scientific reasons, at the invitation of the École Polytechnique in Hanoi, or the Ministry of Higher Education and Training.” Even on his later visits (1976, ’79, ’84, ’90) he continued to intervene with the Vietnamese authorities on behalf of dissidents.

President Johnson, who had announced in March 1968 that he would not seek reelection, halted the bombing of the North in October 1968. His successor, Nixon, expanded U. S. involvement in Vietnam by secretly invading Cambodia and renewing large-scale bombing of major North Vietnamese cities (1970). But the Viet Cong rebels continued to gain in the South, and the North Vietnamese succeeded in shooting down American high-altitude bombers (34 in all, or so). A shaky ceasefire was reached in 1973. But Nixon had to resign in 1974, and in 1975 the war ended, as Saigon fell, and the South surrendered to communist North Vietnam. A unified Vietnam finally emerged. Schwartz concludes: “Vietnam has left its mark on my life. I knew about colonial Indo-China from the book of André Viollis, written in 1931, which I read sixty years ago, when I was twenty. My fight for the freedom of that country is the longest in my life. I have been, and shall always be, fond of Vietnam, its landscape, its extraordinary people, and its bicycles. I am something of a Vietnamese. When I run into a Vietnamese, or hear Vietnamese spoken in a bus, I feel inexplicably happy, even though I do not know the language. My sentimental chord vibrates for that country. Many on the left share those feelings. The Vietnamese, moreover, don’t forget about me, and numerous students from there write to me, calling me ‘godfather of all the Vietnamese’. Sartre also had a right to the title, but I do not believe he would have remained still attached to Vietnam as I am.”

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, a nonaligned, developing country, in December 1979 led to the creation in Paris of an International Bureau for Afghanistan (IBA), of which Schwartz was president. “For reasons of notoriety I was, more or less, the only possible choice.” The purpose of the Bureau was “to defend the independence of Afghanistan against Soviet aggression, without having any illusions about the future of the country after the war.” The Bureau’s work was supported by the European Parliament, the French Ministry of External Affairs, many Western countries, and Japan. The massacres, executions, and tortures that were taking place in that (culturally) remote country were exposed and condemned by the Bureau, and the resulting publicity strengthened, in some measure, the resistance which began to build up, especially in the countryside and in the mountains, with the generous supply of arms and equipment by the United States. Soviet troops had finally to withdraw in February 1989. In a country of twenty million people, one million were dead, and six million were refugees. Schwartz considers this invasion a major historical event of the last quarter of the twentieth century, inasmuch as it brought in its wake the collapse of the Soviet Union. In his view it is Soviet repression which has engendered the civil wars that still rage in Afghanistan. He will not hazard a guess about its future. Interesting is the fact that this was academically the busiest period for him. He collaborated in producing a volume of 570 pages with the translated title Education and Scientific Development in France (1981); he was chairing (1985–89) the Board for the Evaluation of French Universities and was working regular hours in his office four days a week while doing mathematics at home the rest of the time; published seven research articles; and wrote a report on the University of Strasbourg. The style is the man.

The withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan did not diminish Schwartz’s concern for the repression of individuals, particularly mathematicians, in the Soviet Union. The consignment of Leonid Pliousch to a psychiatric clinic on the spurious grounds that he was psychologically disturbed was a blatant attempt to break his will as a dissident, and it redounds to the credit of Laurent Schwartz, Henri Cartan, and Marcel Broué—the Committee of Mathematicians—that they mustered the support of a wide circle of leading mathematicians internationally to press for his release. He was arrested in January 1972 and was finally allowed to leave the country in 1976. Youri Chikanovitch, who had translated a Bourbaki volume into Russian, was another such case: arrested in September 1972 and, after public agitation, released in February 1974. The Committee’s efforts extended also to mathematicians in other countries; for example, Sion Assidon in Morocco, Vaclav Benda in Czechoslovakia, Jose Luis Massera in Uruguay. Well may Schwartz conclude with the words: “Mathematicians carry the rigour of scientific reasoning into everyday life. Mathematical discovery is subversive, and is ever ready to break taboos, and depends very little on established authorities. Many today tend to consider scientists, whether mathematicians or not, as people little concerned with moral standards, harmful, shut up within their ivory tower, and indifferent to the world outside. The Committee of Mathematicians is a brilliant illustration of the contrary.”

Laurent Schwartz is a strategist of ideas, within mathematics and without. He is a great communicator who has drawn huge audiences and conveyed to them the fragrance of research, or the joy of teaching, or the value of freedom. His is a mind whose company is never dull. He belongs to the great libertarian tradition of France. And his book has the very French characteristic of giving serious consideration to the life of the intellect. No man’s life can be encompassed in one telling, yet the spirit of the man and his times is well caught in the Autobiography.

Footnotes

- Harald Bohr was a mathematician and brother of the physicist Niels Bohr.↩