Calyampudi Radhakrishna Rao, popularly known as Dr. C.R. Rao, turned 100 on 10 September 2020. This article is a celebration of his century of distinguished accomplishments at the highest level and his remarkable sense of envisioning the future.

Prologue and Family

As per Indian mythology, Krishna, the eighth avatar of Lord Vishnu, was the eighth child of Devaki and Vasudeva. Coincidentally, Calyampudi Radhakrishna Rao, was the eighth offspring of his parents, mother A. Laxmikantamma, and father C.D. Naidu (1879–1940). Although Rao was universally addressed as “Dr. Rao’’ by all his students and colleagues at the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), where the title “Professor” was reserved exclusively for Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis (PCM), the history of his birth name is quite interesting. He is not only named after Lord Krishna, but his middle name symbolizes the purest form of romance. Rao always claims that though he is a romantic by temperament, all his romance is somehow in the wrong place and that it is in his head instead of his heart! Below we present a photograph providing details about Rao’s lineage and his big family in 1931, respectively.

In 1989, Rao wrote a book Statistics and Truth: Putting Chance to Work [CSIR Ramanujan Memorial Lectures] and nothing is more fitting than his own life as the best empirical evidence of “Putting Chance to Work”. The inspiring story of his joining the ISI in 1941 as a statistics trainee by a chance encounter is a well known one that cannot be recounted enough.

It was a hot summer day of June 1940. World War II (WWII) was raging in full swing with all its devastation, and at the same time promising jobs to the unemployed youth of India. Rao, not yet 20 at the time, set out on a 500-mile train journey from the coastal city of Visakhapatnam to Calcutta, the second largest city of the British Empire, after obtaining a first class degree in mathematics and with a glimmer of hope of finding a job in the military. Rao was not so “lucky’’, as he was deemed too young for the job. However, while in Calcutta, through a chance encounter, he visited the ISI founded in 1931 by PCM, a Cambridge-trained physicist. As a last resort, he applied for the one-year training program in Statistics at ISI, with a letter of recommendation from the vice-chancellor of Andhra University, Professor V.S. Krishna, who was known to PCM. Rao received a prompt positive response from PCM admitting him to the one-year program of the ISI from January 1, 1941. As we all know, the rest is history. In fact, a very long history. Rao did not get the job he came for but found something that would keep him engaged for the next 80 years of his life, an engagement that still continues.

Publications: Two Masterpieces by 30

After Rao passed M.A. in statistics with record marks in 1943, PCM offered him a part-time lectureship at the Calcutta University (CU). In 1944, Rao was giving a course on estimation to the senior students of the master’s class at CU, where he mentioned without proof Fisher’s information inequality for the asymptotic variance of a consistent estimate. There, a bright young student named Vinayak Mahadev Dandekar (VMD), who was of the same age as Rao, raised the question whether such an inequality exists in a finite sample. Rao didn’t know the answer in the class; however, at night in his tiny apartment, with a simple application of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, Rao solved the problem and discussed the result in the next class!

While writing a note on this result for publication, Rao discovered many related results. Since the publication of Sankhyā, a journal started by PCM in 1933, was suspended during WWII, the paper was published in the Bulletin of the Calcutta Mathematical Society.1 Quite interestingly, it was the same WWII that brought Rao from Visakhapatnam to Calcutta and eventually to ISI! Instead of asking what is in this paper, one should ask what it is not? It has, (i) Cramér–Rao inequality, (ii) Rao–Blackwell theorem, (iii) Differential geometry appearing for the first time in statistical literature, and finally, (iv) the Fisher–Rao metric. Any first graduate course in statistical inference will be incomplete without the first two results above. Here, one cannot overlook the origin of Rao’s 1945 paper, i.e., arising from a question posed by the student VMD who later became the director of Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune and did pioneering work on poverty, unemployment and income inequality in India–-a conjunction of a student like VMD and a teacher like Rao in a classroom is not easy to come by!

In his second masterpiece that appeared in the Proceedings of The Cambridge Philosophical Society,2 Rao introduced a new test principle famously known as Rao’s score (RS) test, as an alternative to Neyman–Pearson likelihood ratio (LR) and Wald (W) tests. The seed of the paper was planted in Calcutta in 1944. That too is an interesting story.

S.J. Poti, who joined the ISI as a teaching assistant, found himself without a place to stay in Calcutta. Observing Poti’s plight, Rao offered to share his small single room on the fourth floor of a building. The room had no kitchen; and the bathroom and toilet were shared with all the tenants of that floor. Having no cots, they would spread their beds on the floor to sleep at night, and then roll the beds up in the morning. The two used to go for long walks in the evening, often discussing problems in statistics. One day Poti asked Rao whether the Neyman–Pearson (NP) theory could be used to test a hypothesis about a parameter when the alternative is one-sided. Rao gave an immediate solution that was published as a note in Sankhyā3 which, using the NP lemma, showed that a locally most powerful (LMP) test must be based on the score function, i.e. the derivative of the log-likelihood with respect to the parameter, evaluated under the null hypothesis. This little obscure note can be viewed as a precursor to Rao’s pathbreaking 1948 paper, though the general idea for the RS Test evolved in a natural way while Rao was analysing some genetic data. The problem was estimation of a linkage parameter using data sets from different experiments designed in such a way that each data set had information on the same linkage parameter. Thus, like most of Rao’s work, the RS Test is an example of a statistical method motivated by a practical problem.

The importance of the RS Test in statistics and econometrics cannot be overstated; it is one of the most useful tools in evaluating and testing statistical and econometric models. There are also many well known tests in the literature that were suggested long before 1948, whose theoretical foundation can now be buttressed by the RS Test principle. As mentioned above, the RS Test requires estimation of the score function only under the null hypothesis, thus facilitating a huge simplification of the final form of the test statistic. In most applications, RS statistic has a simple closed-form expression which is quite unthinkable for the LR and W tests.

One of us (Bera) has a first-hand experience in using the RS Test in devising the following widely used test for normality, popularly known as the Jarque–Bera (JB) statistic first published in 1980:4

\[\begin{align*}\mathrm{JB}=\sqrt{n}\left[\frac{(\sqrt{b_1})^2}{6} + \frac{(b_2-3)^2}{24}\right],\end{align*}\]

where n is the sample size, and \sqrt{b_1} and b_2 are, respectively, the sample skewness and kurtosis. The JB test was derived using the Pearson system of curves as an alternative (to normality) hypothesis, for which LR and W are almost impossible to apply. Not only does the RS principle lead to a neat and beautiful expression, but it also uncovers the optimality implications, namely LMP, of using sample skewness and kurtosis. JB and its various extensions have around 8,000 citations. It won’t be an exaggeration to say that Bera’s entire livelihood has been based on the RS Test!

We can pick up each paper of Rao and go through its origin and underlying history; however, that would be a very long exercise not suitable for this essay.

Dr. Rao’s research has had significance beyond statistics and econometrics, like the quantum Cramér–Rao Bound that provides sharper versions of Heisenberg’s Principle in quantum physics. He has made a major contribution to the combinatorial theory of design by extending the notion of orthogonal Latin squares through the notion of orthogonal arrays.5 In the last two decades, he has also touched upon non-linear methods, resampling methods, neural networks, and data mining. It is inspirational to see how a man, who, on the verge of crossing a century, is determined to stay up-to-date in the mainstream of modern statistical learning and data mining.

Rao, The Master Guide

After Raj Chandra Bose and Samarendra Nath Roy left ISI in 1949 and 1950, respectively, and PCM got busy with national planning, Rao became the natural successor to the leadership of research and training of the institute, and was the doctoral thesis adviser of many bright students. Over his full academic life, Rao has directed the research work of more than 50 Ph.D. students who, in turn, have supervised 350 Ph.D. students of their own.

About our very own Professor Ranga Rao at UIUC,6 we note, “Ramaswamy Ranga Rao is a prominent Indian mathematician. He finished his Ph.D. under the supervision of C.R. Rao at ISI, Calcutta. He was one of “the famous four” students of Rao in ISI during 1956–1963. Ranga Rao is now professor emeritus of mathematics at University of Illinois. He made fundamental contributions to statistics, Lie groups, and Lie algebras.” The four–-K.R. Parthasarathy (KRP), Veeravalli S. Varadarajan (VSV), S.R. Srinivasa Varadhan (SRSV) and Ramaswamy Ranga Rao (RRR)–-are known as the fabulous four in ISI legend. VSV joined the institute in 1956 and in a marked departure, instead of statistics, decided to work on probability theory, and started his research career by learning the necessary mathematics by himself within a year or so. RRR and KRP became partners of VSV, and quite coincidentally like VSV, they also had B.Sc. Honours degree in mathematics from the University of Madras. VSV completed his Ph.D. in 1959, and in the same year SRSV came to ISI as a Ph.D. student. SRSV later went on to receive the Abel prize of the Norwegian Academy of Sciences in 2007. Like each of the previous three, he also did B. Sc. Honours from Madras before coming to Calcutta. Although, at times helped by the brilliant statistician Raj Bahadur, it was Rao who provided encouragement and guidance to these four students. Rao created a wonderful academic atmosphere for young scholars to carry out their perennial discussion on mathematics, most of the time conducted in Tamil. There is a funny anecdote about a non-mathematician and non-Tamilian, who claimed to have learnt a Tamil word “ergodicity” from overhearing this intense discourse taking place among them.

Dr. Rao had an unorthodox modus operandi while guiding Ph.D. students. His first Ph.D. student was Debabrata Basu, whom he recruited in 1950. The celebrated Basu’s theorem arose out of a question Rao put to Basu, about the existence of maximal ancillary statistic. Basu proved the nonexistence of such a statistic, and in addition, established the independence of an ancillary statistic and the minimal sufficient statistic. In a recent interview in Bhāvanā,7 KRP mentioned that, on the advice of C.R. Rao, he read the Mathematical Foundation of Information Theory by A.Y. Khinchin,8 but was not satisfied with one particular chapter. KRP rewrote that chapter which involved learning some ergodic theory and about the probability measures invariant under transformation. KRP sent it to Joseph L. Doob of the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, who in turn gave it to measure theorist John C. Oxtoby. Oxtoby wrote and published a paper giving full credit to KRP.9 In those days, there were no regular fellowships at ISI and whatever Rao decided was the scholarship amount. When KRP showed Oxtoby’s paper to C.R. Rao, his scholarship was doubled. That was the kind of incentive Rao provided to his Ph.D. students.

During the 1962 ISI convocation time, Dr. Rao asked KRP and SRSV to suggest a prominent scientist from USSR who could be invited. The duo suggested the most famous of all, the legendary probability theorist A.N. Kolmogorov (ANK). Rao’s response was simply, “No problem. We will get him.” Rao put a word to PCM who in turn put in the right word at the right time to the USSR Academy of Sciences. ANK, possibly the most important visitor that ISI has ever received, came on 14 April 1962 and stayed till May 12. ANK’s visit testifies the importance Rao paid to students’ needs and suggestions. The visit was a huge morale booster for not only the fledgling young ISI probabilists but also for the whole of India, all the more as ANK rarely travelled outside USSR.

Rao’s guidance went far beyond Basu and the fab-four. During the 1960s, Rao had five or six students working for a Ph.D. at any given time, including I.M. Chakraborti in design of experiments; R.G. Laha in characterization problems; J. Roy in multivariate analysis; A.C. Das and Des Raj in survey sampling and A. Matthai on quality control. Very substantially if not wholly, the cluster of these brilliant and creative Ph.D. scholars of C.R. Rao enthroned the ISI to its golden period during the 1960s.

Rao’s Foresight on Computer Technology

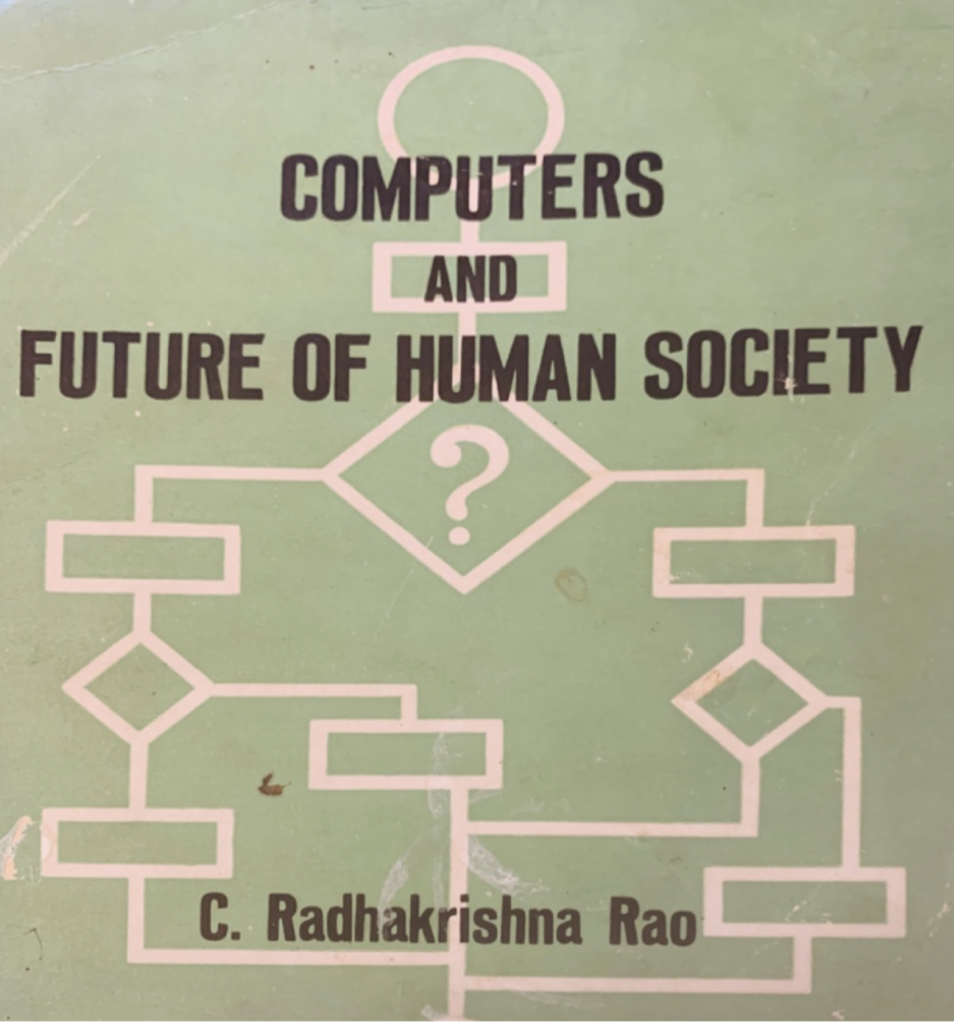

Long before the era of digital revolution, Rao wrote the book Computers and Future of Human Society published in 1969.10 Being a visionary, he anticipated that the path to economic development and prosperity was tied to the use of the computers, at a time when less than 1% of the world knew the use of computers. In his words, “We need computers to guard our land frontiers and the long coasts, save us from floods and fury of storms, defend ourselves against external aggression, improve our agriculture to feed the teeming millions, give the best education to our children, help in better medical diagnosis and save the lives of patients, and provide the people with necessary comforts, facilities and opportunities in life.”

He traced the history of computers, both hardware and software and analyzed questions like: “Is the human brain superior to the computer? Are we likely to succeed in producing a robot identical with human beings in all respects except in origin?” that were much ahead of their time. He laid out that computers can prove to be a great boon for a developing country like India, to close the productivity gap with some of the advanced countries of the world. But he also admitted that there is a dangerous possibility that robots controlled by computers would run factories, and today it is not a secret that many jobs have been lost to automation.

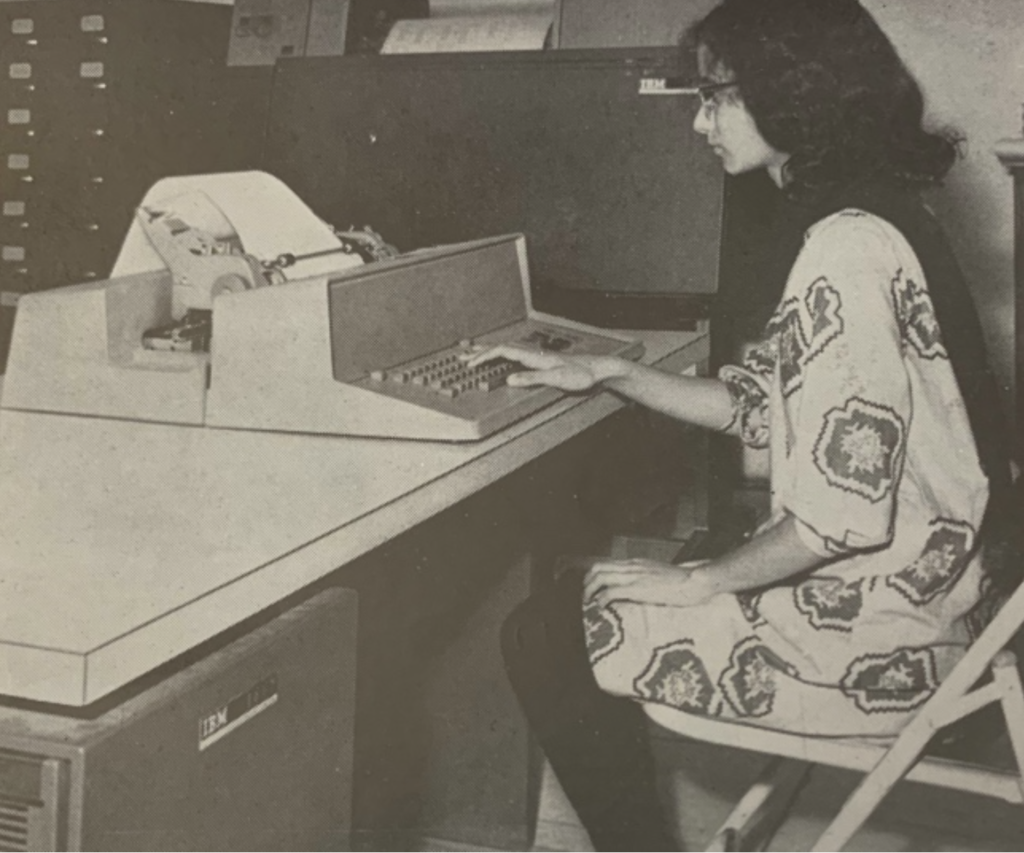

He pretty much forecasted that the future of the world lies in computer programming, as we are now witnessing it every day in our lives. The field of computer programming, especially machine learning is experiencing an exponential growth today, while in Rao’s time, computers were hunks of machinery the size of a room. Rao wrote about Anne (shown in the photo below), “She is looking forward to the day when such a console typewriter is installed in her home as telephones are now. She can utilize the computer, which may be far away, sitting at her home and at any time.” Rao anticipated that the day is not far when a computer console will be installed in every home and almost envisioned that one will be able to utilize it at any time to get access to any type of information, like checking email, surfing the internet and having all kinds of data at one’s fingertips. Rao perceived the world with computers in ways that we never thought was possible.

The Women Behind the Man

Rao dedicated his book Statistics and Truth: Putting Chance to Work, to his mother, A. Laxmikantamma, and credited her “For instilling the quest of knowledge” in him and “who woke him up every day at four in the morning and lit the oil lamp to study in the quiet hours of morning when the mind is fresh.” Rao remembers his mother as a great disciplinarian, and she controlled the daily activities of her children, prescribing the time for playing, studying, and sleeping. This regiment later helped him in leading a disciplined and successful life. He had very little contact with his father until he retired as he was a police officer that required him to be working at different locations.

Rao was fortunate to have parents who fostered his innate abilities with proper guidance, provided an environment conducive to study, and gave a framework for ethics of life. He himself admits that genetics played an important role in his achievements and goes on to say “I inherited my father’s analytical ability and my mother’s tenacity and industry.’’

On returning from Cambridge to India in August 1948, Rao got married on September 9, a day before his 28th birthday. In the initial days of their marriage, Bhargavi struggled to keep up with the activities of Rao; however, she soon realised the importance of the work that he was doing, and adjusted herself to the life of an academician. She supported Rao and provided him with an environment at home to pursue his research peacefully. She had two master’s degrees, one in history from the Banaras Hindu University in India and another in psychology from the UIUC. In Calcutta, she worked for some years as a high school teacher and for a number of years as a lecturer. Rao and his wife were happily married for over 65 years, before she passed away in 2016.

Mrs. Bhargavi Rao narrated a funny anecdote about her husband, in the book, Putting Chance to Work; A Life in Statistics: A Biography of C.R. Rao by Nalini Krishnankutty,11 published in 1996. Once a visiting scientist came from the Soviet Academy of Sciences, to meet with Dr. Rao in person. He knocked on the door, which was opened by Mrs. Rao, and enquired about Dr. Rao. He was amazed that like the Soviet scientists, Dr Rao did not live in a big guarded house. She told him that her husband was downstairs near the car. He replied that he had only seen a mechanic working on the car, but not C.R Rao. Then Mrs. Rao informed him that it was not just any mechanic, he had actually seen The C.R. Rao. The visitor returned in the evening and saw Rao playing badminton with his colleagues and the next day he went to the ISI office to meet the Director of ISI. To his surprise, Dr. Rao was the director, sitting in a room resembling a cubicle with only the flap door closed and easily accessible to everyone. Dr. Rao invited him home for dinner and welcomed him like a perfect host, with vodka and Russian caviar. The visitor while leaving the house exclaimed, “I have seen the mechanic, the athlete, the scholar and the perfect host, all in one day.” Like Lord Krishna had several names and roles, Dr. Rao successfully wore many hats.

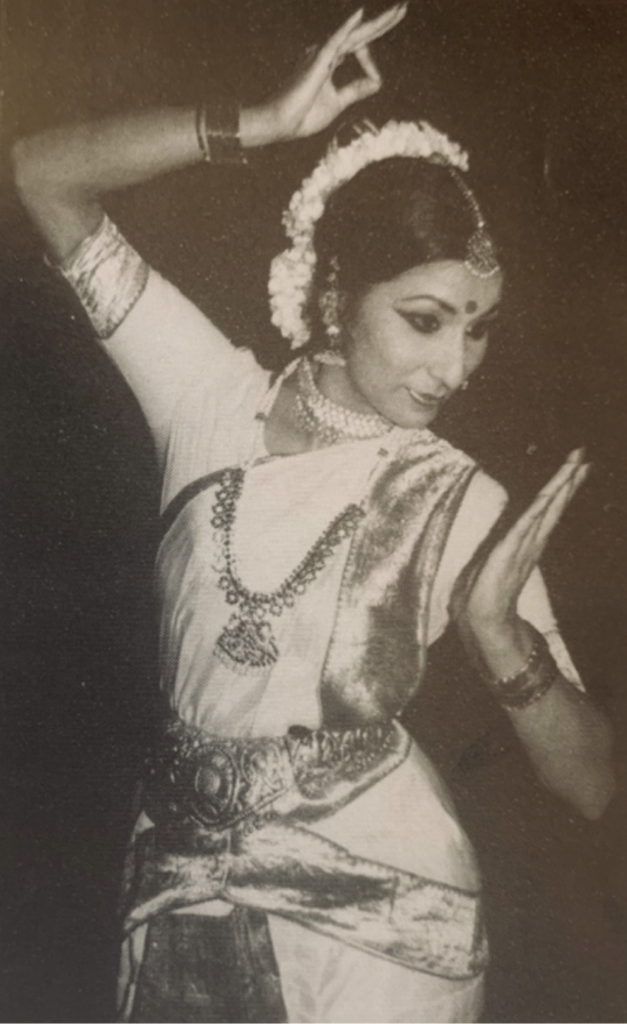

Rao’s daughter Tejaswini is an accomplished Indian classical (Kuchipudi) dancer and runs a dance school. She has a Ph.D. in nutrition and is a Professor at SUNY, Buffalo. In 1970 Rao moved to ISI, Delhi and was surprised to find that there was no dance school to teach Kuchipudi. Because of his interest in Indian classical dance, Rao started a Kuchipudi Dance Academy in Delhi and was its President until he left for the USA in 1979. Rao and his wife admitted Tejaswini in a dance school at the age of eight. When she performed in public, Rao often supervised the performances, the music, the introductions, and the lighting. No matter how busy he was he would always take the time to ensure that the performance was well-planned. He made her do demonstrations of abhinaya,12 and render English translations of her dance music. This is very common now during Indian dance performances, but it was unheard of in the early 60s. So, in this matter too, Rao was well ahead of his time. Rao had an artistic vision and dancers today follow techniques that were made for Tejaswini more than half a century earlier.

Tejaswini admits that she and her brother Veerendra didn’t know much about their father during their stay in India, as Rao never talked much about himself. It is only after he moved to the U.S. that they learnt about him as a scientist. As a person he is very sensitive and caring, with a great but subtle sense of humour. His family wished that he would take some time off to enjoy with them; however, Rao’s greatest pleasure in life comes from being immersed in work and research.

Rao Modesty and Magic

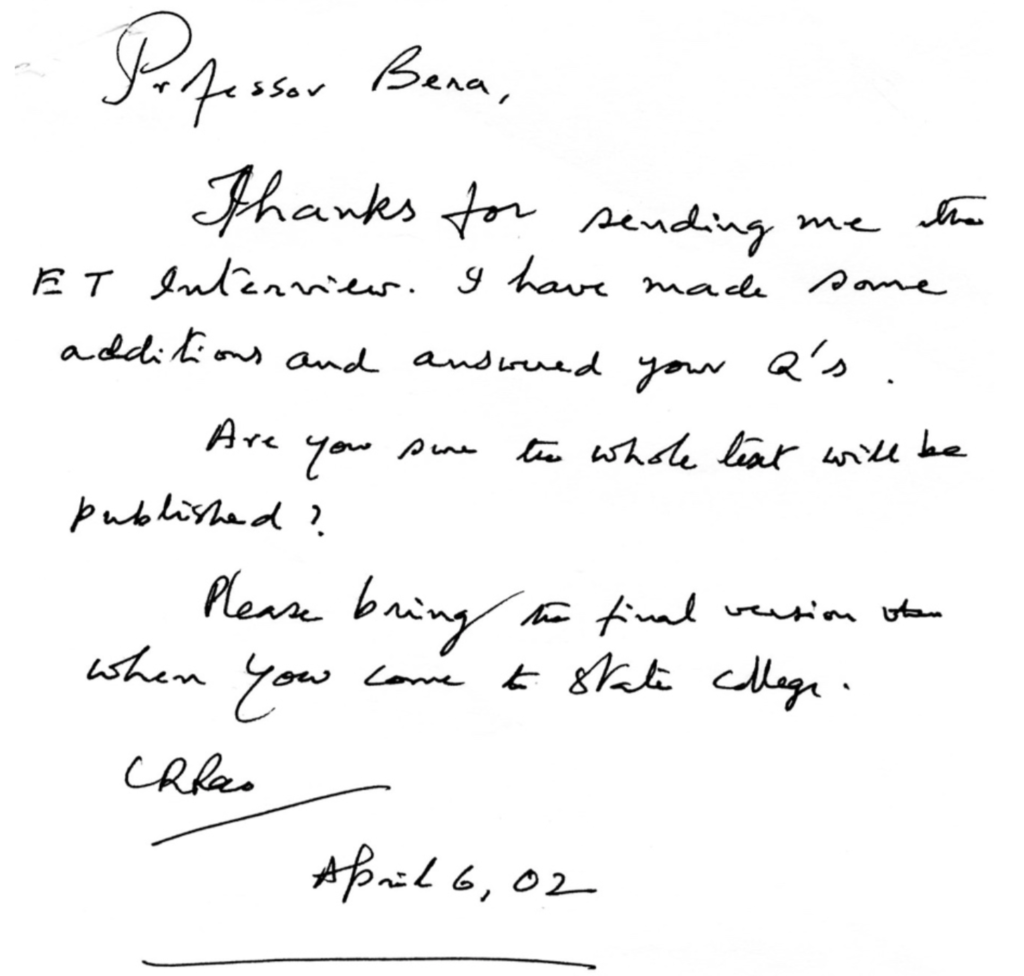

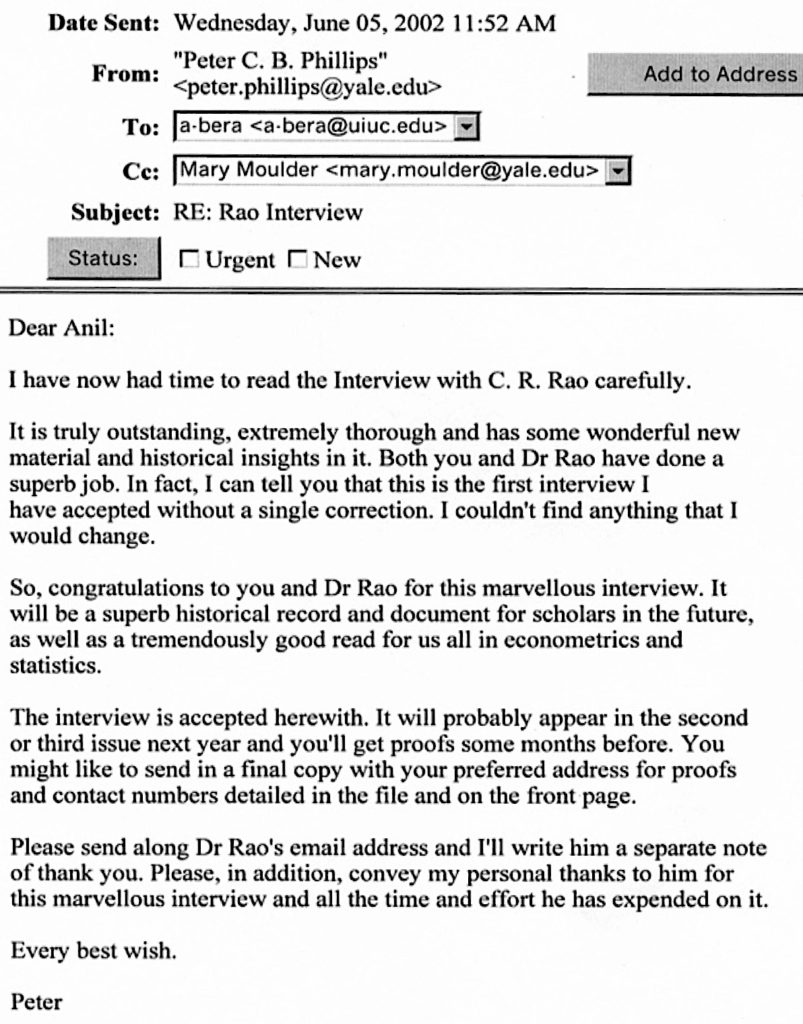

One of us (Bera) was involved in preparing the Econometric Theory Interview with Dr. Rao,13 at the invitation of the editor, Professor Peter C.B. Phillips. As the interview went along, it grew longer and larger, and at one stage, it was almost 100 typed pages. Rao became worried and his modesty was expressed as “Are you sure the whole text will be published?”, as in the handwritten note below.

|

|

With a lot of trepidation, Bera submitted the interview to ET on 31 May 2002, expecting a response in a few weeks from the Editor, most probably with a lot of suggestions to cut down the size. Quite surprisingly, within a week, apt came the Editor’s letter of acceptance without a single correction! This is simply Rao magic.

Not only that, the Editor also sent the following email to Rao:

Dear Professor Rao:

I am writing to thank you for the time and effort you put into doing the Interview with Anil Bera for the journal Econometric Theory.

The interview is a delight to read, is thoughtful, wide-ranging, and contains some wonderful historical insights. In addition to being a marvelous interview, I believe it will be a superb historical record and document for scholars in the future. I am confident it will be read and enjoyed by all econometricians and, I’m sure, the much larger community of statisticians.

Thank you once again. And congratulations to you and Anil Bera for such a superb job. Your interview will appear in the second issue of 2003.

With respect and best regards,

Peter C.B. Phillips

Here, quite fittingly, the Editor marvels at the historical insights provided by Rao that will be read and enjoyed by not only econometricians but the wider community of statisticians.

Epilogue and Celebrations

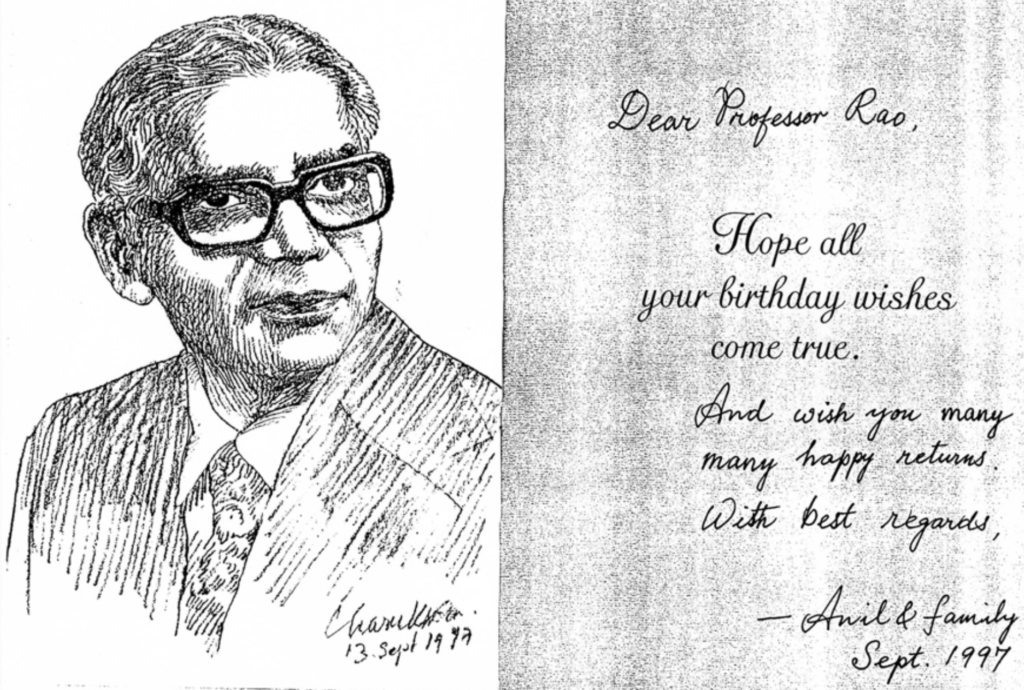

Given that my academic career started with the RS Test and still continues, I (Bera) have always been in touch with Dr. Rao for research and on special occasions. None of my emails/letters have gone without a prompt reply from Dr. Rao. I wish I were equally prompt with his letters and emails. On the occasion of his 77th birthday in September 1997, I sent him birthday wishes with a sketch by eminent Indian artist Charu Khan. Rao appreciated it very much and sent a warm reply back.

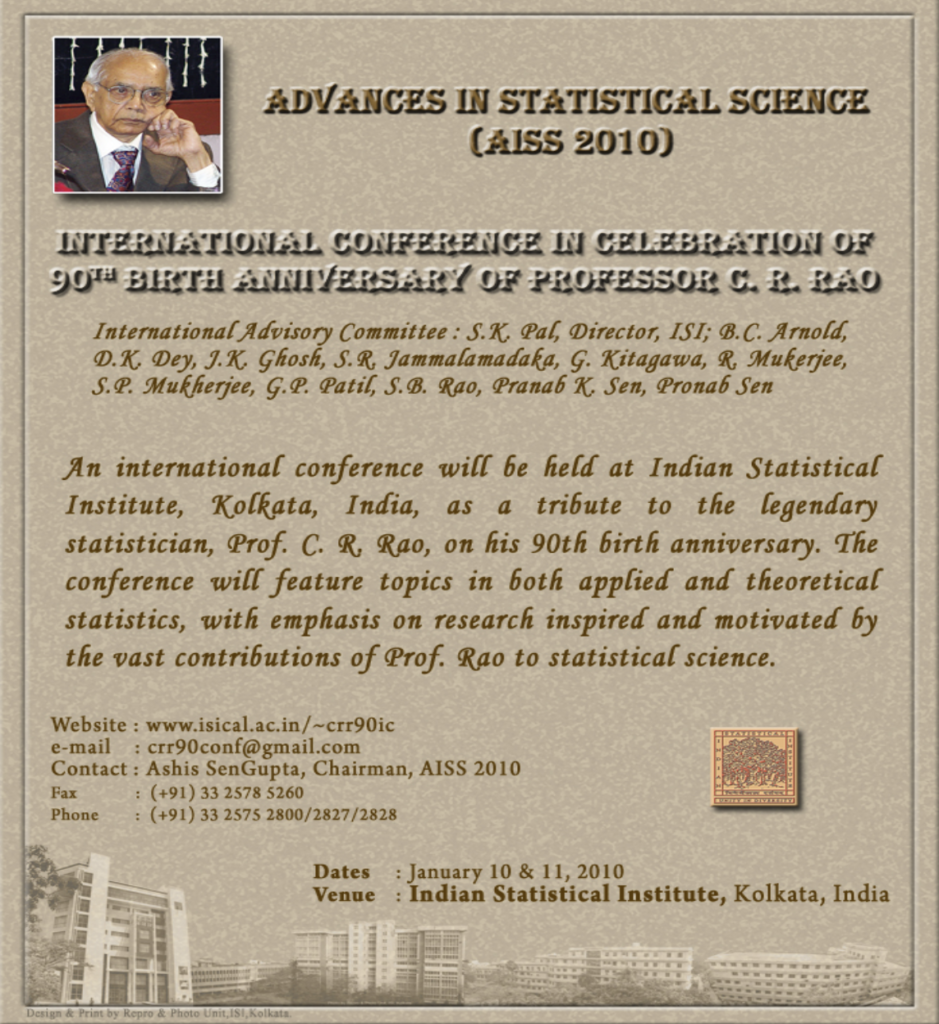

Rao is recognized internationally as a pioneer who laid the foundation of modern statistics, with multifaceted distinctions as a mathematician, researcher, scientist, and teacher. His contributions to mathematics and to the theory and application of statistics have become part of graduate and post-graduate courses in statistics, econometrics, electrical engineering, and many other disciplines at most universities throughout the world. Rao is loved and respected all over the world. His birthdays are celebrated by the entire econometrics and statistics community with great enthusiasm, internationally.

For his outstanding research contributions, C.R. Rao has been honoured with the establishment of an institute named after him: C.R. Rao Advanced Institute for Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science (AIMSCS), in Hyderabad, India. It is a fitting tribute to Rao, since he hails from this part of India. The institute is engaged in cutting-edge research in the areas of statistics, mathematics, computer science, wireless communication and other interdisciplinary fields. Fittingly, the C.R. Rao Birth Centenary Celebrations started at the AIMSCS on his 99th birthday, September 10, 2019 with a video message from Rao himself.

In his message, Rao said, “I was fortunate to have made some fundamental contributions to the field of statistics and to see the impact of my work in furthering research. In my lifetime, I have seen statistics grow into a strong independent field of study based on mathematical, and more recently computational, tools. Its importance has spread across numerous areas such as business, economics, health and medicine, banking, management, physical, natural, and social sciences. Statistics is the science of learning from data. Today is the age of data revolution. There is therefore, a heightened need for statistics–-both in terms of training in statistics to help analyse and interpret the data, and in terms of research to answer new questions arising from the data’’.14 This succinctly sums up the long statistical journey of C.R. Rao, and also indicates that it is the data science that is stored for the future of Statistics.

The 2019 International Indian Statistical Association Conference at Mumbai, India during Dec 26–30, 2019 brought together statisticians worldwide from academia, industry, government, and research institutions to explore the latest developments and challenges in the era of data science and statistical learning. For that occasion, Tapan Nayak, a former Ph.D. student of Dr. Rao organized the C.R. Rao Honorary Session which included the following presentations:

- “A new all-purpose generic multivariate transformation with applications in multivariate modelling and missing value imputation’’, Ravindra Khattree, Oakland University.

- “Analyzing periodic and nearly periodic data: Statistical perspectives’’, Debasis Kundu, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur.

- “The Trinity: Professor Mahalanobis, Dr. Rao, and the ISI’’, Anil Bera, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

Incidentally, Shailaja Suryawanshi of Merck & Co., who also spoke in the Session was the last Ph.D. student of Dr. Rao to graduate from the Pennsylvania State University in 1996 with a dissertation titled, Analysis of High-Dimensional Data in Problems of Regression and Discrimination, with Applications to Size and Shape Analysis. The Session was very well attended, followed by a very lively discussion.

Of course, there will be many more tributes coming to Rao in the coming months and years analyzing his research contributions. However, we should not forget the man, or the “life” behind all the work–-the humble and the unassuming person. Here we can only borrow a couple of lines from Rabindranath Tagore to express our feelings for Rao, “You are greater than your achievements. The chariot of your life leaves your achievements behind, time after time.”

acknowledgement We would like to thank Professor Arijit Choudhuri for his kind invitation to contribute an essay on the occasion of C.R. Rao centenary. We are also thankful to Yufan Leiluo for his comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this essay. All omissions and misreadings are ours. \blacksquare

Footnotes

- Rao, C.R. 1945. “Information and accuracy attainable in the estimation of statistical parameters.” Bulletin of the Calcutta Mathematical Society 37, 81–91. ↩

- Rao, C.R. 1948. “Large Sample Tests of Statistical Hypotheses Concerning Several Parameters with Applications to Problems of Estimation.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 44, 50–57. ↩

- Rao, C.R and S.J. Poti. 1946. “On Locally Most Powerful Tests When the Alternatives are One Sided.” Sankhyā 7, 441. ↩

- Jarque, C.M., and Bera, A.K. 1980. “Efficient Tests for Normality, Homoscedasticity, and Serial Independence of Regression Residuals.” Economics Letters. 6, 255-259. ↩

- Bera, A. and Lu, C. 2017. “Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis A Renaissance Man and the Father of Statistics in India.” Bhāvanā. July 2017.1(3). ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._Ranga_Rao. ↩

- B.V. Rajarama Bhat. 2019. “A Different Kind of Mind: K.R. Parthasarathy in Conversation with B.V. Rajarama Bhat.’’ Bhāvanā. Apr 2019.3(2). ↩

- Khinchin, A.Y, 2013. Mathematical foundations of information theory, Dover Books on Advanced Mathematics, New York. ↩

- J.C. Oxtoby. 1961. “On Two Theorems of Parthasarathy and Kakutani Concerning the Shift Transformation.’’ In: Ergodic Theory, Proceedings International Symposium. Tulane University, Academic Press, New York, 203–215. ↩

- Rao, C.R. 1970. Computers and the Future of Human Society. Statistical Publishing Society, Calcutta. ↩

- Krishnankutty, N. 1996. Putting Chance to Work; A Life in Statistics: A Biography of C.R. Rao, Dialogue Publishing. ↩

- Abhinaya is a word for expressiveness in Indian dramatics. ↩

- Bera, A. 2003. “The ET Interview: Professor C.R. Rao: Interviewed by Anil K. Bera”, Econometric Theory 19, 331-400. ↩

- B.L.S. Prakasa Rao. January 2020. “C.R. Rao: A life in statistics”. Bhāvanā. 4(1). ↩