The article recollects the strong influence of the values instilled in him by his paternal grandfather as a child, his formative years as an impressionable mathematics student in constant financial stress and then as an eager yet struggling student at TIFR, to a blooming mathematician under the tutelage of Samuel Eilenberg despite his initial reluctance to travel abroad for his PhD and finally his TIFR homecoming, all the while interspersed by fond recollections of his charismatic and candid demeanour by many of his collaborators and dear friends from the mathematical community such as C.S. Seshadri whom he helped in the running of the CMI. Most of all, his legacy as a great mathematics teacher who could also be a source of support for his students in their troubled times is every bit as enduring as his mathematical one.

Written about eight years ago, the time I spent interacting with Sridharan and several of his admirers then is a treasured memory for me.

In the last week of July 2015, a bunch of mathematicians huddled around in a seminar room of the Chennai Mathematical Institute, for an event that brought much cheer and happiness to all those who had congregated there.

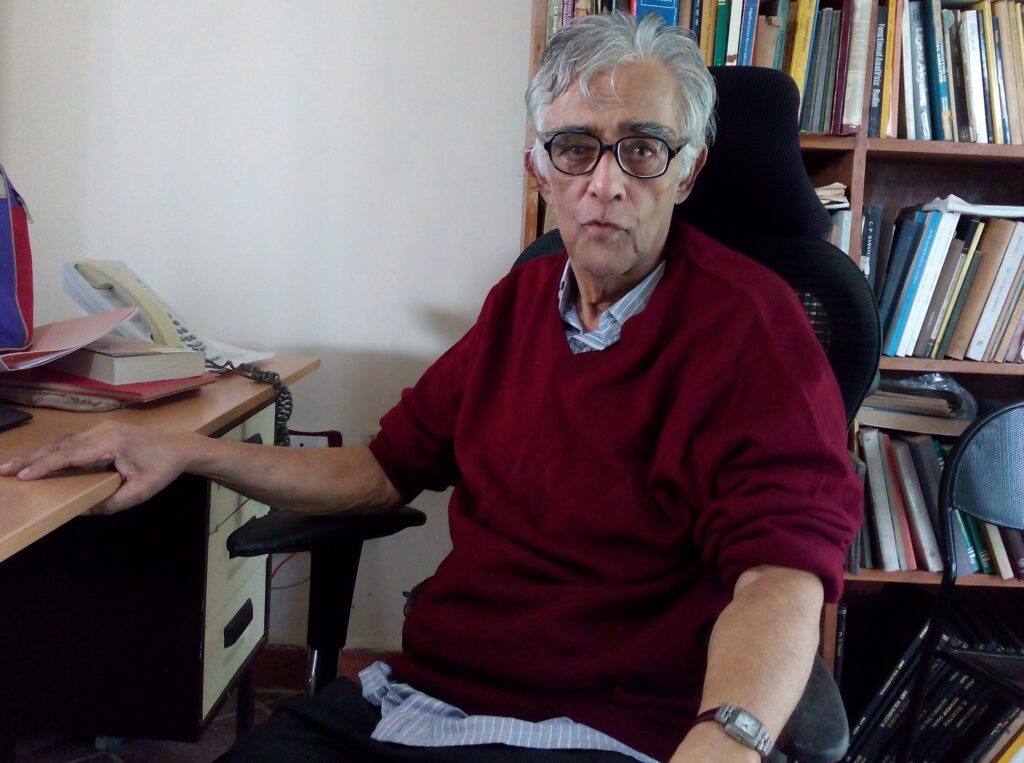

They were there for a special event, the 80th birthday celebrations of a man much loved, revered and cherished. The man who had brought the mathematicians together, himself appeared a little uncomfortable in those settings, even complaining to anyone who might give him a sympathetic ear that the whole thing was not in the least required, let alone be fussed about. The man in question is the very wise, learned, and deeply revered Ramaiyengar Sridharan. Sridharan had just turned 80 a few weeks ago, and it was time to celebrate the man, his thoughts, his works, and above all a worldview that is as rare as it is precious.

Sridharan was born on the 4th of July, 1935 in Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu, in the home of his maternal grandfather, renowned advocate Srinivasachari. He belongs to a family of ardent followers of the Srivaishnavite tradition, which itself owes its origin to its patron saint Sri Ramanujacharya, the eleventh century saint who propounded the Vishishtadvaita school of spiritual thought. Sridharan’s surname itself though is a typical conjoining of a first name, with the word Iyengar, an occurrence quite commonly seen in those days. People from this sect, over many centuries, and even in the modern era, have typically demonstrated a strong tradition of excellence in Vedic thought, university education, and more relevantly, in path breaking original research, with the name of the legendary mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan as an oft-quoted typical example.

The genealogy on his father’s side was quite illustrious. His paternal grandmother was the daughter of the Dewan of Travancore, Dewan Ramaiyengar, and in whose name, an eponymous street off the Poonamallee High Road exists, even to this day in the western suburbs of Chennai. His paternal grandfather, Rajagopalachari, was trained to be a lawyer, but demonstrating a strong sense of ethics, refused to practise law, stating that it frequently took a lie to succeed in the legal profession, and that he would be better off without having to cheat and lie, in order to eke out a livelihood. He was also a great scholar of Sanskrit, Tamil and English literature, and authored an English translation of Sri Ramanujacharya’s commentary on the Bhagavadgītā, and an English translation of Thiruvalluvar’s Kamathupal. He was very well versed in Ayurveda too.

As a young boy, Sridharan was deeply influenced by his paternal grandfather. In a way, the strong sense of ethics that Sridharan himself is known for, his amazing erudition that sits so lightly on his shoulders, coupled with a humbling humility, are all qualities that his own paternal grandfather was known for. Righteousness, selflessness, virtues of scholarship and erudition were not the only inheritances that came by Sridharan’s way. He also inherited stubbornness, a refusal to accept injustice when he saw it, and to correct which, he was prepared to go long and unreasonable distances.

There was a lot of quality that young Sridharan was exposed to in his early life. A rather high dose of virtues and culture that his keen mind saw, observed, enquired about and then gleefully gulped in large measures, one might wit. Resulting in the making of a man with impeccable ethical character, quality and sense of purpose. A truly blessed existence. Yes, indeed. But there was another side to the Sridharan story of those days, and that was the family’s material existence. Time had been busy at work, and a family that had once boasted of a Dewan in its ranks, had indeed fallen on hard times. During the time of the First World War, the family owned a large estate and many bungalows in Chennai, but was compelled to sell off in a hurry all their property for a pittance, to move to Cuddalore, where Sridharan’s maternal grandfather lived. Consequently, his own early life was a curious mixture of some financial stress, and extraordinary internal growth. He recalls to this day, wistfully and ruefully gazing at a long gone distant past, the fact that those times were so hard, that his father even gave away along with the bungalows, many original paintings by no less than Raja Ravi Varma himself, which his family had inherited owing to an illustrious past

TIFR was a very attractive option for people wanting to study cutting edge mathematics in India

It was under these circumstances that Sridharan started off in life. He studied up to 4th form in St. Joseph’s School, Cuddalore. The family shifted back to Chennai around 1950, and he studied 5th and 6th form in Ramakrishna Mission School, North Branch, Chennai. It was during this time that Sridharan got interested in mathematics, thanks to a very inspiring mathematics teacher, P.V. Ramachandran. He studied Intermediate (today’s 11th and 12th Classes) at Vivekananda College, Chennai, and went on to study there for three more years for his BA (Honors). He graduated from Vivekananda College, obtaining a BA (Hons) from Madras University in 1955. During his collegiate studies he was also greatly inspired by one of his mathematics teachers, K. Subramanian who encouraged Sridharan to take up mathematics as a profession.

Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Mumbai was then a very attractive option for people wanting to study cutting edge mathematics in India. He decided to go to TIFR, a decision that was to prove decisive and hugely important in the young man’s life. He arrived in Mumbai in 1955, joining the School of Mathematics of the TIFR in 1955. K. Chandrasekharan and K.G. Ramanathan were the mathematicians in the two member selection committee. With his typically disarming candour and humility, he says that he was indeed quite surprised that he was selected at all. In the first year, he studied analysis, algebra and topology. The first year was also a year in which some people made strong impressions on him. The mathematician scholar K. Balagangadharan taught him analysis. T.P. Srinivasan and K.G. Ramanathan taught him algebra. B.V. Singbal taught him topology. Four other students also joined in 1955 – N.S. Gopalakrishnan, K. Varadarajan, K. Srinivasacharlu and a girl named Kalindi B. Vedak.

The students had to face an interview at the end of the first year of study. There was a strong sense of independent study in TIFR, contrary to the environment that one would have seen in a conventional university in India at that time, or for that matter, even now. But the TIFR was anything but conventional. The brainchild of an institution builder par excellence – Homi Jehangir Bhabha, TIFR was conceptualized to be a centre of excellence. And the pursuit and achievement of excellence was not only encouraged, but also expected. Students were both not only driven hard, but also given enough freedom to form their own impressions. They were free to choose to do what they pleased, but they had to be not just good, but also excellent in whatever they chose to do. In some sense the interview at the end of one year of study was a make or break event. Students either stayed on, or they left never to return. That in essence was what a research student did in TIFR those days.

Another classic that he had taken an instant liking for, was Claude Chevalley’s Lie Groups

Sridharan’s interview at the end of the first year was eventful, to say the least. The same professors who had hired him were also the ones in the exam committee. Things went unexpectedly, and way below Sridharan’s own expectations. He was nervous, fidgety and totally uneasy. In the first year of being a student at TIFR, Sridharan’s interests at that point were in algebraic topology, and particularly in homotopy theory. It was a set of ideas that he had picked up from the classic book by Samuel Eilenberg and Norman Steenrod, and also from Hilton’s Homotopy Theory. He had taken an instant liking for the ideas there, and strongly wished to pursue those ideas further. Another classic that he had taken an instant liking for, was Claude Chevalley’s Lie Groups. The committee however was not satisfied with his performance, and before they let him off with a strong warning, also told him that he may be asked to leave if he didn’t pull up his socks in the coming days. So he stayed on, tenacious and eager to make amends. He was nervous, anxious and in some sense annoyed with everything and everyone. He was to face this situation of feeling being horribly straight jacketed, again and again in the days to come in his own professional life. A familiar enemy, he would comfort himself much later in life, whenever he felt that the old enemy had come back, but when he first encountered it in 1956, he almost threw in the towel. There was another thing that was bothering young Sridharan those days. His family always had a financial crisis and 1955/56 was no different. Sridharan’s monthly stipend at the TIFR was Rs. 175, out of which he used to save Rs. 50, and which he used to send to his family every month. But now his own tenure was on shaky ground, and added to this there was another looming financial problem. Sridharan had had to borrow a rather large sum of money those days, Rs. 2,500 to be precise, from a dear Physicist friend of his, R. Vijayaraghavan, towards the wedding expenses of one of his sisters. The thought of whether he would be able to repay the debt that he owed his dear friend at all or not, that too when his own stay in TIFR could not be taken for granted, weighed heavily on his young mind. It was an albatross he quickly wanted to unburden himself from around his neck.

Tenacity is what he learnt then. He gulped the whole unsavoury episode down, put his nose to the grindstone, and tried to forget the whole thing. Reminiscing on those days, he fondly recalls memories of his good friend Vijayaraghavan who lent him a helping hand, and how their friendship has since lasted generations literally. Literally, generations. Never one to miss an opportunity to indulge in witty wordplay, he says he repaid the debt in good measure. Much later on, he married Vijayaraghavan’s sister. A debt that resulted in the forging of a great friendship, many great friendships in fact.

Around the same time, in 1957, an English mathematician by the name of C.H. Dowker visited TIFR, and lectured on sheaf theory. It appealed to Sridharan a great deal. It impressed him so much that he went up to Dowker, and asked him to suggest a problem to solve. Dowker in turn pointed to a paper of J.W. Alexander, which had appeared in a then recent issue of the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. Dowker hastened to add that though he himself could not guide the young Sridharan, he did feel that Sridharan might benefit if he took a good look at the paper to later discuss it with Samuel Eilenberg, an eminent algebraic topologist from Columbia University, who was soon due to visit the TIFR. Sridharan did look at the paper, and started working on it. In the meantime Eilenberg arrived, to lecture on homological algebra. He was there on his second visit, having already visited the institute earlier. Sridharan met Eilenberg and told him about the paper of Alexander that he was reading. Eilenberg was very kind and told him that he should lecture to him on the paper the next day, and in the meantime he took it with him to study it. Sridharan went to Eilenberg the next day to give the lecture but then Eilenberg told him that he already had looked at it, and that he believed that the paper would not lead him to much. He also told him: “May I suggest that you attend my lectures here on homological algebra? I am sure you would find problems to solve.” He also gave a small problem in algebraic topology to Sridharan to solve, which he said he needed for one of his own works. An excited Sridharan went to his room that evening, worked on it, and before day break had solved it. He had to be sure of it though, and so showed it to Singbal, who had taught him topology. Singbal said it was fine. When he showed his solution to Eilenberg the next day, Eilenberg asked whether he had done it by himself, or whether he had taken someone’s help. Sridharan said that he had done it himself, but that he had gotten it checked by Singbal. Eilenberg was quite pleased with the proof, and asked him to get it typed and give it to him. (But due to administrative bureaucracy in TIFR, Sridharan was unable to get it typed in the maths office, and so Eilenberg never got a typed version!)

Eilenberg lectured on homological algebra, an area of mathematics that he lay a high claim to, by virtue of being one of its co-creators along with Henri Cartan. He had a solid body of work to show, was known all over the globe, and had impeccable credentials as a first rate research mathematician. Sridharan sat through his course on homological algebra. In fact he thoroughly enjoyed the experience. Apparently suitably impressed by Sridharan, Eilenberg went back to Columbia, and sent him an offer to join the Columbia University Mathematics Department, on a prestigious fellowship that went by the name of the Higgins Fellowship. In fact, he wrote to K. Chandrasekharan, and said that he very much wanted Sridharan as his student in Columbia. This was a great boost to Sridharan’s confidence, especially as it came after a nerve wracking academic session following the disastrous first year interview. It also greatly helped that the man who had taken a personal interest in him was a world renowned mathematician with impeccable credentials, and also to top which, the chairman of a large Ivy League mathematics department. It could not have gotten any better. Except that Sridharan did not want to go. Inspired by the beautiful lectures of Eilenberg, Sridharan had already started working on homological algebra in TIFR on his own; and had published two single author papers, along with a joint paper with two of his colleagues, all in homological algebra. He often missed Chennai, while still in Mumbai, and he knew that he would be very homesick at Columbia. He also felt that a PhD would take a lot of time. So he refused, and instead of him, his batchmate Varadarajan, who was interested in working with Harish-Chandra (who incidentally was then at Columbia), was sent by the institute to accept this fellowship. But Eilenberg was a man who would not take no for an answer, and the very next year again sent him the same offer, with the same scholarship. This time, Sridharan had run out of excuses.

Sridharan landed in Columbia, and Eilenberg used his good offices to ensure that he did not have to go through the rigmarole of doing all the course work that the department expected of new students. Eilenberg saw to it that Sridharan was given a few credits as soon as he joined (out of the mandatory 60 credits which a graduate student of Columbia had to earn), and was asked to earn the rest of the points in one year, so that he could start off on a thesis problem as early as possible.

The Higgins Fellowship paid a handsome amount for a nine month period. Eilenberg, who was always very fair to all students, asked Sridharan to share a part of his fellowship with Varadarajan, who by then had already completed a year at Columbia, and was getting an ordinary scholarship, just so that they both got the same amount of money. In his first semester in Columbia, he cleared the qualifying examination and within a year he completed the course requirements. During this period he attended two courses – one on measure theory, and another on the theory of distributions and differential equations – by Harish-Chandra, a course on algebraic topology by James Eells, a course on differentiable manifolds by Paul Smith, a course on noncommutative algebra by Earl Taft, and finally a course on homological algebra by Eilenberg. He recalls the course that Harish-Chandra taught on distributions vividly. The man was meticulous, and perfect to a fault. On one particular occasion, while teaching the theory of distributions, Harish-Chandra got stuck at a point. Serge Lang, a member of the maths faculty at Columbia, and who was also attending this course, suggested to Harish-Chandra that he leave it as an exercise to the students. Harish-Chandra got annoyed, and shot back asking how he could leave it as an exercise to the students, that too when he himself could not then solve it!

Sridharan recalls the course that Harish-Chandra taught on Distributions vividly. The man was meticulous, and perfect to a fault

When Sridharan started off his research at Columbia, Eilenberg did not really believe in giving out thesis problems. He however suggested that Sridharan could perhaps read a recent paper by E.C. Zeeman on “Filtered Differential Groups”, which had just then appeared in the Annals of Mathematics. He also told Sridharan that he felt that Zeeman had somewhat “missed the bus” in that paper, and that it may be worth looking at anew, this time from the perspective of the so-called “Word problem”. Sridharan plunged into it, worked very hard on it for months, and obtained some partial results. He went and showed it to Eilenberg, who looked at it. Eilenberg, though apparently pleased with the progress, surprisingly suggested to Sridharan that he could also start working on some other problem of his own choice if he so wished. Sridharan felt very depressed, and felt that he was at a real dead-end, because indeed, he had no other problem to work on at that time. And also the one that he had worked so hard on, incessantly and for many months at, did not sadly seem to be capable of making Eilenberg’s cut.

During his comprehensive examination at Columbia, all the key members of the mathematics department were there, and they asked him a variety of questions. The examination went off well, except that at one point Sridharan got stuck in the proof of the “Hilbert Basis Theorem”. Also, surprisingly, Lang just got up in the middle of the proceedings and left. The very next day Sridharan met Lang on Broadway and Lang confessed to him that he left because he felt upset that the committee was being rather needlessly tough on the young man.

There used to be weekly maths colloquia on Wednesdays in Columbia. (Incidentally, Eilenberg’s teacher, the great Polish mathematician Karol Borsuk came once to speak in the colloquium. Since he could not speak in English, Eilenberg translated the lectures and it was very heartwarming to see Eilenberg’s dedication to his teacher). But the visit of Alexander Grothendieck to Columbia, is the one that Sridharan remembers with great vividness. This event was a watershed moment in his life, which surprisingly and unexpectedly left him feeling extremely dejected.

He decided to go back to India, and become a school teacher since he didn’t see any point in doing mathematics when people like Grothendieck were active in the field. He consoled himself thinking that he was not that bad after all, as he still could try his hand at literature, music, poetry, and Sanskrit. So he waited for an opportunity to throw in the towel. He chose Christmas, and knowing that letters would take longer to get delivered, posted it just before Christmas. In the letter that he wrote to Eilenberg, he expressed his inability to be creative enough, or come up with anything that was worthy of Eilenberg’s attention. He also begged his forgiveness, and asked that he be forgiven for not being able to live up to the promise that his mentor had seen in him. He also said in the same letter that he could never be a Grothendieck, and that he would like to go back to India and become a school teacher.

After listening to Paul Smith, Sridharan had to change his mind and eventually decided to stay back at Columbia

During the Christmas break though, he used to spend time in the famous Butler Library at Columbia every day. As luck would have it, one day Paul Smith, one of his teachers in his very first year at Columbia, came to the library and met him. He asked Sridharan whether he could have a word with him in one of the library cubicles, and sitting there, he said that Eilenberg had indeed told him of the letter that he had received from him. Sridharan did not know how to react. Smith then said something which Sridharan says, still rings in his ears to this day, many, many decades after he first heard it. “You are not the only person that Grothendieck has managed to send into a depression. Lang told me that even he was so depressed, that he even contemplated giving up mathematics fully, after he interacted with Grothendieck in Paris. You should forget trying to be someone else. We are all good in our own ways. I think you are good, and I believe you will do well in mathematics. Can I go and tell Eilenberg that you have indeed reconsidered your decision?”

After listening to Paul Smith, Sridharan had to change his mind and eventually decided to stay back at Columbia. It is interesting to note Eilenberg’s reaction a few days later, when Sridharan accidentally bumped into Eilenberg coming down the stairs in the mathematics department. Eilenberg winked at him, which by the way used to be his usual way of expressing pleasure, and told him: “So, you have changed your mind and are going to stay with us. Good, I will ignore your letter to me.”

Eilenberg thought that it would be a good idea for Sridharan and Varadarajan to spend the summer of 1959 at the University of Chicago, and attend a summer school on homological algebra scheduled to be then held there. They both stayed at the International House in Chicago. Sridharan did not particularly enjoy the lectures. However he had the opportunity to meet among other algebraists, G. Hochschild whose work on cohomology of algebras he was very familiar with. In fact the earlier work of Sridharan in Bombay had used Hochschild cohomology. Hochschild was very pleasant to Sridharan and when Sridharan said he was looking for problems to work on for his PhD thesis, Hochschild suggested the computation of a specific cohomological dimension as a question that he could start thinking about. The very next day Sridharan went back to Hochschild and showed him a solution. Hochschild was very happy to see it. However, the very next day, he met Sridharan to tell him that there was a mistake in his proof, and in fact a fellow mathematician Irving Kaplansky with whom he had discussed it, had a ready counter-example. Needless to say, Sridharan was once again hit by an enemy all too familiar to him by then.

During his stay in Chicago, Sridharan read not only many books from the library of the international guest house, but he also had taken along books on mathematics, philosophy, and physics, all of which he had bought from the Columbia university bookstore. This included the wonderful book of Hermann Weyl, translated to English and published by Dover titled Theory of Groups and Quantum Mechanics. Incidentally this is a book which he loved and still loves. In this book, he came across the famous Heisenberg uncertainty principle which simply says that the commutator of the differentiation operator and the multiplication operator in one variable is the identity operator. Familiar as he was with Hochschild cohomology, Sridharan wanted to study the cohomology of the algebra generated by these operators, and in fact proved the vanishing of the first Hochschild cohomology group of these algebras with coefficients in themselves, and in characteristic zero. When Sridharan told Hochschild about it the next day, Hochschild was extremely pleased and told him that it must have something interesting to do in quantum mechanics, and that Irving Segal would be interested in such a result. Sridharan just wanted to be doubly sure that there were no false alarms this time though. He was determined to ensure that!

However, Sridharan did not talk to anyone else in Chicago. When Sridharan went back to Columbia after his stay in Chicago, Eilenberg greeted him and asked him how his stay in Chicago was and whether it was fruitful. Sridharan said that the only thing that he could do was a small piece of work, and also about which, he was really not too sure if it was interesting enough. He nevertheless still began explaining the result to him. But Eilenberg, as usual, said that he would like to see a written version. Sridharan went back the next day with a manuscript. Eilenberg was very happy and said that it did look quite interesting, and that it should be also possible to study the question more generally for Lie algebras. In fact this remark essentially led Sridharan to his PhD thesis, of course with Eilenberg’s ever willing and generous help.

Sridharan decided to return back to TIFR after submitting his thesis. However, Eilenberg who knew that Sridharan had never been at ease in the time he had spent at Columbia generously suggested “After all, you don’t have to worry anymore about your thesis. Why don’t you spend a few more months and do mathematics for pleasure, completely for the joy of doing it, and without any deadlines?” Sridharan agreed and he was supposed to stay for a few more months at Columbia. However, his father fell ill in India and he returned to India in November ’60. Overall, America had been good to him. He went there a tentative youngster, still unsure of his footing, but returned a confident man, head brimming with ideas, and with the energy of youth. He felt lighter and freer than before. America and Sridharan had to find each other, in hindsight. For a man who revels in connecting the abstruse with the arcane and later finds even greater joy in simultaneously demystifying both, it must have been pretty plainly obvious that they had to seek each other. Did someone mention that they shared the same birthday?

In 1967 he was invited by the ETH-Zurich, and there began the collaboration with Manuel Ojanguren and, later, with Max Knus. Ojanguren, who has known him from 1967 onwards to this day, was very much present in the conference in CMI.

Reminiscences

Beginning with Ojanguren, below are reminiscences of some of Sridharan’s admirers and long acquaintances present at the July 2015 conference in CMI.

Manuel Ojanguren

I met Sridharan for the first time in 1967 in Zurich, at the Forschungsinstitut für Mathematik (FIM), founded by Beno Eckmann two years earlier. I had just joined the FIM after finishing my PhD, and I was rather confused about my future research.

In those years the FIM was swarming with category-theorists and I was tempted to just follow the crowd, but Sridharan started a course on algebraic K-theory, and from the first lecture I no longer had any doubts about what to do. The subject had been recently developed by some excellent mathematicians, like Bass, Serre, Schanuel, Swan. The techniques used were algebraic but the inspiration was largely topological.

And Sridharan’s lectures were just perfect: not a word too much, not a missing detail. We started discussing some mathematics connected with his lectures, then he suggested that we try to solve a problem on projectivities over commutative rings, which we did. This led to our first joint publication, in 1968. We then switched to a different topic and wrote a short article on purely inseparable extensions. I think that the particular location of the FIM also contributed to our collaboration. Although it belonged to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) it was not located in the main building but occupied an anonymous old house, in a narrow lane, isolated from noise and traffic, with no other people around except a dozen mathematicians.

Every afternoon the secretary would serve tea with cookies and in no time we all knew each other, and it really felt like a very special little community. Another factor which contributed to the pleasant atmosphere of the small institute was certainly Sridharan’s personality. Very soon his office became the natural gathering place for mathematical discussions. In fact I almost stopped using my own office and, in the morning, directly went to his. I observed the same strange attraction exerted by his office on fellow mathematicians later at the Tata Institute and I suppose the same is happening now in Chennai.

In March 1968 we were invited to the first meeting of the Séminaires des Plans-sur-Bex, a series of annual seminars where some invited mathematicians would lecture, during one week, to PhD students of the Swiss-French universities. There we met Edoardo Vesentini, the director of the Scuola Normale of Pisa. Apparently he liked our contributions and invited us both to give a seminar in Pisa, where we spent one pleasant and instructive month in early 1969. The only difficulty in Italy consisted in conveying to the waiters the notion of vegetarianism. Sridharan was not very flexible on this point and in every restaurant, hearing that meat was excluded, the waiter invariably first suggested ham, then fish, then eggs. Sridharan soon realized that he had to live on pizza margherita and spaghetti al pomodoro and cheerfully accepted the inconvenience.

Before leaving Zurich he suggested that I spend one year in Bombay, at the TIFR. I was thrilled at the idea of visiting India, a country in which I had a romantic interest, probably sparked by a comic strip version of the Ramayana that I had read in my childhood. So I enthusiastically accepted his invitation and we continued our collaboration in Bombay.

Although I did not fully realize it at that time, meeting Sridharan in Zurich was one of the turning points in my life. He not only knew much more mathematics than I did, but he had excellent taste and a very sharp eye for details. We also had other common interests, one of them being languages. He had told a mathematical colleague, Peter Gabriel (at that time at Zurich University) that during his stay in Zurich he wanted to learn either to drive or to speak German. Gabriel observed that driving was rather trivial, but learning German would be a real achievement. So he gave up the idea of driving and concentrated on German, learning it rather quickly and so well in fact that he taught me some idioms I did not know.

Books were another common interest. What mostly amazed me was his ability to spot them. Stroll in a suburban area of Bombay where books are sold on the pavement or go into some dark second-hand bookshop in Zurich – in a heap of silly uninteresting books he will spot, at twenty paces, the only gem, the only book worth reading. In the same way, he will immediately spot an interesting reasoning in a mathematical paper or a particularly beautiful passage in a book. He himself describes one of his adventures with books in an article entitled “Plum in the middle of Bombay” which appeared in the Independent2 of 2 June 1991. The subject of this article is the search for a book quoted by P.G. Wodehouse, a book whose very existence was not obvious, as it could have been (as most readers were probably inclined to believe) the author’s invention. As everybody knows, Sridharan is a great expert on Wodehouse and can quote extensively from any of his novels. People sometimes think that I am quoting Shakespeare when in fact I am quoting Sridharan who is quoting Wodehouse who is quoting Shakespeare. Sridharan’s penchant for wordplay generally appears in light conversations but it once manifested itself in print when he proposed the title of our joint paper (with Parimala) “Ketu and the second invariant of a quadratic space”. I had to explain to the printer that, yes, we meant K_2 as he surmised, but we still wanted to use the name of that demoniacal planet, because demoniacal were the difficulties we had encountered. Between 1969 and 1995 we met several times in Bombay and in Switzerland, and a few times in other places, sometimes in connection with a mathematical event, sometimes for longer visits. I can say that I enjoyed every moment I spent in Sridharan’s company. This visit is just no different as I catch up with my friend on the happy occasion of his turning 80. I wish him many more years of maths, poetry, Latin, and all that he loves and excels doing at.

C.S. Seshadri

C.S. Seshadri,3 the mathematician who founded the CMI, had over a 60 year long association with Sridharan and has known him for a duration that only a few others can boast of. Below are many thoughts that Seshadri shared with me during two very long telephone chats:

I joined TIFR as a student in 1953, and Sridharan joined in 1955. We have known each other for the last 60 years. When we were students, TIFR was in a big churn.

We had many visiting professors from the top research universities in the world, and luckily we also had an extremely talented bunch of students too. Sridharan belongs to that era and that calibre. We heard that Eilenberg had a very high opinion of him, and that he had liked Sridharan’s thesis work very much.

Even here in CMI, his contribution to teaching and research is immense. CMI started in 1989, and he came here in 2000. CMI had just then, only two years before in 1998, started its undergraduate program. It is here that I want to place on record Sridharan’s yeoman service to the teaching program at all levels, and especially at the Bachelor’s level. Many of the brightest students from CMI who have gone on to do wonderful things both in India and abroad, actually directly owe a lot to Sridharan. His role in our attempts to establish CMI as a top destination for world class undergrad maths education in India is truly commendable. His amazing connect with students was a big plus, as he was always willing to help, and they simply flocked to him. His connect with people was so amazing that he even taught Tamil to people who wanted to learn the language. He is one of those people who do not differentiate between teaching and research. His great scholarship, his amazing and refined sense of humour, his exceptional talent with languages, wide knowledge of literature, poetry, and history easily endeared him to many students. I believe that his teacher, Balagangadharan, had a deep influence on him as far as his inclinations in Sanskrit, literature, and poetry go. To top it all, he is a great raconteur, and will keep you amused and hooked with stories and anecdotes for hours on end. We have had no conflicts at all these 60 years and, today, we are more than just friends. In fact we are more of family friends now.

I recall one incident where his scholarship and his wide ranging interests came to the fore, and in an interesting way. It was the time when we were debating on what we should do in CMI? We wanted to emulate the great universities of the west, where teaching and research go hand in hand. And are not separate entities at all. Also, it was important to keep a mathematician’s mind busy, and teaching would keep people busy and not allow them to get rusty. This was important because we had seen that even the best mathematicians tended to slow down in their creativity after a point, and completely stop too, in some other cases. Even Grothendieck slowed down dramatically after the 70s, and he was still only in his mid-40s then. Also, we were not keen on an institute that did only research, like the IAS, in Princeton. Because in India such institutes are not easy to sustain for various reasons.

From my own experience in Harvard, I saw Raoul Bott, a great mathematician offering a course in differential calculus. I came back thinking what is it that we were doing? We needed to understand these things well. Creativity, many a times, does not need a great many necessary conditions. But scholarship has many necessary prerequisites. And by stressing on scholarship as the primary leitmotif of a university, research and teaching get automatically subsumed within this broader and more pragmatic theme. Sridharan made these things quite clear to all of us in a most surprising way. He pointed us to an article by the French-American educator Jacques Barzun. In this article, Barzun clearly mentions exactly the same argument which Sridharan himself had so clearly articulated, in discussions with all of us. We were all quite amused, and also quickly convinced that this was indeed the right philosophical approach to take, but as far as Sridharan’s ability to come up with a source that was not just original, but which also perfectly addressed our question, we were not in the least surprised. Sridharan’s own breadth and depth of scholarship was never in doubt to us at all. I wish him great and robust health, and hope that his quick and eager mind continues in its myriad quests for a long time to come.

Parvati Shastri

During his long stay in TIFR Mumbai, Sridharan mentored, guided and graduated many students. A mathematician, formerly of the University of Mumbai, Parvati Shastri has these lovely words to say of her mentor:

This is a tribute to my teacher/grand teacher, who has just turned 80.

Professor Sridharan played a very significant role in my journey from being an amateur to a professional. I met Sridharan for the first time, when he was on the interview committee for awarding Junior Research Fellowships of the UGC, in Bombay (now Mumbai), in 1971, as a candidate. I was quite impressed with his approach, and the way he interviewed me, and I developed a great regard for him. Later, when I took up the fellowship, I attended his lectures on algebra in TIFR and my regard for him grew even more. But soon, I discontinued my studies due to practical difficulties.

Nevertheless, my inner desire to do research remained unfulfilled, and definitely I was interested in Algebra, although I had some inclination to Number theory as well. I made some stray, unsuccessful attempts to study independently but with little success. Later, after a long gap of some 12–13 years, sometime in 1985 or so, I had the opportunity to live on TIFR campus in Bombay. So I decided to resume research in mathematics. But I was neither a fresher nor did I have enough background to pursue research on my own. I had only some vague ideas from my past experience, most of it forgotten. It was then that I approached Sridharan and expressed my desire to do my PhD under his guidance. The first thing Sridharan asked me was, “Do you want to write some thesis and get a degree, or do you want to do mathematics seriously and write a good thesis”? I said, “I want to do good mathematics, and at least I would like to give it a fair try”. That was it. Immediately he said, “In that case, you should come here (to the Tata Institute) every day for two-three hours, regularly and study”. That `regularly’, every day was very important, because, I was any way going to the School of Mathematics of TIFR, on and off (irregularly), and either sat in the library or spent some time in my husband’s office, trying to study something aimlessly, without any focus. Also, Sridharan told me that he had stopped taking students, but that Parimala would be my guide officially, and that we would all be working together. Then, both of them told me, “You can come here any time, ask any question and discuss anything that you do not understand!” That was great, unheard of, contrary to the experience I had with professors in TIFR in general! Gosh, he could have thrown a few questions that I could not answer and shooed me away, saying I was unfit for research, if he had so desired! Instead, I was allowed to ask any question! That already filled me with the courage to go ahead, which I very much lacked at that time. After that, I did go every day for two-three hours, asked questions, sometimes stupid and sometimes clever and I started enjoying `doing mathematics’ in their company. I could also witness how they studied new things, how they thought from scratch and how they applied their knowledge and skill, to prove a new result. In short, these were practical lessons on how one does research. From two-three hours a day, soon it increased to four, five, and six and so on and within a few months, I started working for ten to twelve hours or even more, every day, regularly. Sridharan used to meet students (not just his or Parimala’s), between 9–10 pm in his office every day. I started going to him at that time and lecturing to him on what I was reading. I was vague and unable to give proofs of what I was stating. But he always listened to me carefully and patiently and corrected my mistakes. Never did he criticise me or humiliate me, for my ignorance or mistakes. I would hesitatingly say to him “All these results may be known, no?” And he would say, “nothing is known I say; you should keep thinking about it and prove it”. Every time I talked to him, my understanding improved and I got more involved in my studies. One day I gave a nice argument to give an affirmative answer to a question, (which I myself had asked him earlier about, and as usual he had told me that I should try to prove it myself), and he was quite happy with my argument. He remarked, “This shows that you can think!” As far as I was concerned, it immensely boosted my morale and elevated my self-esteem. Initially, I was very timid, hesitant and shaky. But now, I was more confident and rigorous.

Although I was given special respect for my age, as far as the quality of the work was concerned, there was no compromise and I was treated like any other student in TIFR.

Sridharan is a perfectionist and a task master. But he has a very pleasant way of inducing people to work. For instance, when I could not come up with any solution to a problem that I was trying to solve, for a few days, he would say “you have slept over it for a long time, I say; you should finish it now!” Well, this sort of compulsion really helped me a lot. While writing my thesis (those days we wrote by hand, and gave it to the typist for typing), I would take whatever I wrote every day, and show it to him. He would read it so fast and in no time, he would point out so many mistakes, typos and I had to go back and do it all over again, spending several hours! Sridharan has tremendous memory, intelligence and scholarship. He is a great supporter of women. He understood the difficulties women like me faced, in maintaining equilibrium between home and career. He was (and he still is) very compassionate and always helped us overcome our difficulties. He is a great teacher in the true sense of the word. Three years of my association with Sridharan during my PhD days, to begin with unofficially and then officially, put me in motion, and on a sound career track. The work culture and the perfectionist’s attitude that I developed under his supervision, during those years, came in handy for the next twenty years in my career, till I retired from the University of Mumbai, as a professor. I am really thankful to Sridharan for guiding someone like me at that stage, a full-fledged housewife in her late thirties with two children, and transforming an amateur into a professional. Under his supervision, I got the right environment and encouragement that I very much needed then.

Amit Kulshreshtha

The thoughts expressed above by Parvati Shastri, are incidentally sentiments that are reflected quite strongly and repeatedly by two young mathematicians who came under the tutelage of Sridharan, and these testimonials bear testimony to the fact that Sridharan’s popularity and connect with students is as strong as ever. Amit Kulshreshtha, a faculty member at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Mohali and another PhD student of Sridharan, who was present at the 80th birthday celebration fondly recalls:

It was August 1999 when I joined TIFR as a Research Scholar. All faces were new and some of them seemed lost. I knew only my batchmates, some seniors and our course instructors. An unknown gentleman with uncombed grey hair, casual slippers and a sweater knotted like a scarf around his neck used to greet me with a smile in corridors and lifts. While I had a sense of gratitude that my presence was being acknowledged by someone unknown at a new place, I did not dare to ask back who he was. I had no clue that this gentleman would turn out to be a great teacher, a wonderful mentor and would have a deep impact on my life. That was my initial interaction with Sridharan.

I distinctly remember his first lecture. It was a live concert! I was spellbound

A couple of weeks later he began to teach us topics in category theory in our first year algebra course. I distinctly remember his first lecture. It was a live concert! I was spellbound. How can one have such a beautiful choice of words to express some of the most abstract ideas under the sun?

During his lectures he used to create an atmosphere that would unify the audience with the topic and concepts would just flow naturally. Almost every evening after dinner he used to visit the students’ office located in C-337 of TIFR, to help us with the entire coursework, including topics of analysis and topology. Then he would offer us a coffee in the East Canteen. I gained through him, not just mathematics, but other beautiful and meaningful things of life as well. His passion and proficiency in literature is well-known among the mathematics community. I have two personal reminiscences to share. In 2000, a couple of days before moving to CMI he was clearing his office room at TIFR during night hours. I knocked on the door and saw him reading something from an old notebook. These were excerpts from Kalidasa’s Abhijñāna Śākuntalam in his own handwriting. He obliged me by reciting that poetry. He then narrated his four decade long association with that office room. He was sensitive and philosophical in his description. In fact, these two character traits are completely visible even in a five minute conversation with him.

He narrated his four decade long association with that office room in TIFR. He was sensitive and philosophical

Another incident happened around his seventieth birthday celebrations, held at the University of Hyderabad in July 2005. In response to the felicitation on the occasion, he had recited beginning lines from Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost. After about ten days or so, he visited TIFR, and I asked him if I could get those lines from him. Of course, he said yes. After sometime when I reached my office, I saw that excerpt on the blackboard in his own handwriting. I thanked him in his absence and took its photograph. He never declined any request that I made – like a fruit bearing tree that always has something to offer.

Nivedita Bhaskhar

Nivedita Bhaskhar of Emory University,4 probably one of the youngest of his students at CMI recalls:

Professor Sridharan has been a very inspiring teacher. His lectures which I attended whilst at CMI were a joy to listen to, for he would start with something extremely preliminary that even the mathematically young would feel very much at ease with. Unobtrusively, he would build the theory and towards the end of the lecture, you would suddenly realize that he has been talking very non-trivial maths. And you always came away convinced you’d understood every single word. I think there are very few lecturers, especially in higher mathematics, who can teach without intimidating the students. His lectures would always be peppered with quotes and sayings, which we would from time to time, go back home and look up!

He is also perhaps one of the kindest people I’ve met, always taking an almost paternal interest in each and every student’s affairs. Though he shuns from actively imposing his views on anyone, his time and wisdom are graciously and freely given (often at much personal inconvenience to himself). One only needs to ask! Perhaps like Karna,5 he hasn’t learnt the art of saying `no’! He is a voracious reader; his house is filled with tomes and tomes of books, carefully preserved and read through. Apart from Sanskrit, he is also extremely well-versed in German (Folklore about Sridharan goes that while he was in Germany, he was told either to learn how to drive a car, or learn German. You can guess which option he chose!).

It is always a pleasure to read anything written by him, be it mathematical or non-mathematical. Elegance is perhaps the apt word which best characterizes his writings. He has a very inspiring legacy of students who are mathematical giants in their own right and I’ve had the immense privilege of learning under some of them too.

K. Chandrasekharan

Here are words from a mathematician uniquely placed to throw light on the life and works of Sridharan. He is none other than K. Chandrasekharan,6 the man who was personally invited by Homi J.~Bhabha, when the former was in IAS, Princeton, to found and set up the School of Mathematics in TIFR. The nonagenarian, now an Emeritus Professor at ETH Zurich, was also in the two member committee that interviewed a young Sridharan seeking admission to TIFR, and a little later, as the head of the School of Mathematics, also was the one who received the letter from Eilenberg offering Sridharan the prestigious Higgins Fellowship. Over the years, the two men have had a great many warm interactions, and regularly correspond with each other too.

Sridharan counts among the mathematical dream children of Hermann Weyl. One has only to look into the origin of his doctoral dissertation from Columbia University and his presidential address to the Indian Mathematical Society. Much of the credit goes to him for the pre-eminence of algebra in the mathematics of India today.

He is happy to help others, even happier when his students flourish, as Parimala will agree. His capacity to communicate, innovate, and collaborate, is remarkable, as Knus will agree. They have, along with kindred spirits, built a bridge of algebra spanning Switzerland and India, pointing towards new horizons. Of profound interest are his researches into the structural relationship between mathematics and music. Blessed is the Institution that has supported his work. Twice-blessed are his friends, colleagues, and collaborators. My celebration consists in saying so.

Conclusion

What are your thoughts on the history of ancient Indian mathematics?

Sridharan: There are two broad ways in which we can see mathematics. One is the Indian way, and the other is the Greek way. Our way of looking at things is necessarily application oriented. A prominent example that comes to my mind is the one on enumeration problems in combinatorics. These things must have come about when our ancestors were confronted with problems in prosody, garland making, mixing many individual herbs to manufacture a fine smelling herbal perfume, and other mundane things that they perhaps faced in their daily lives. The Indian tradition in combinatorics was almost completely discovered by Pīngala. Concepts that had come to their notice back then include what are today known as Fibonacci Numbers, Pascal’s Triangle and so on. Sār̄ngadeva and Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita later generalised these ideas considerably. Recently we literally stumbled upon a remarkable formula for the factorial function, thanks to an old work of Sār̄ngadeva. I can say that this is a subject that needs to be studied in greater detail, in order to unearth many more such gems that are part of our rich cultural and mathematical heritage. My own interests in both ancient Indian mathematics, as well as in Sanskrit are due to two people, both of whom I met in TIFR, namely my teacher Professor Balagangadharan, and Professor Rangachari, a senior colleague in TIFR.

There were people in the conference who spoke glowingly about your mathematical works, all of which are very impressive indeed. I also saw a fair number of women in the conference who, on the other hand, looked at issues that fall outside mathematics, and which border on the ethical and the humane. They made it very clear that if there was a hand that steadied their ship, which incidentally did rock many a time, it was you. What is it that made you empathize and act proactively on issues related to women, long before it became fashionable to be seen in that light?

Sridharan: I do not want to see it as an issue that only affects women. But of course, if it affects a woman, society must act with greater alacrity. But at the same time, what I only have done is, to do the right thing at all stages of my life. All my students, be they Amit Roy, Parimala, Sujatha, Parvati, or Suresh, or anyone else, at one point of time or another, have had a problem, personal or professional. And in each of those times, I have tried my best to help them get out of trouble. I even got into some tight spots trying to help them out, but I was stubborn to get my point through because I knew that I was doing the right thing. I can also say with conviction that I never desired any personal gain in any of those situations. It is the conviction that comes out of doing the right thing, I guess.

As we were having these discussions, a strange and unexpected thing happened. A lady security officer working in CMI, came to his office and asked for permission to meet the professor. Even as I was seated in my chair, the lady took off her footwear, came into the room, bowed, and touched Sridharan’s feet, who by then had stood up and asked what she had come in for. She said that she had come for his blessings, and to also wish him well on his 80th birthday. Sridharan thanked her, and replied in Tamil that his wishes and blessings were always with her. And all of this happened completely naturally, and without any fuss or fanfare. There was no unease, nor was there any hesitation or inhibition. Just a great deal of trust, even an amount of faith maybe. How rare, I thought. How often does one get to see that in a research institute, or in any academic environment? Beautiful. Precious.

In the days and the weeks that went by after the conference, I kept pondering about that lady security officer; and her simple act, which had me in a bind to find an explanation to. I kept going back to Sridharan’s good old pal Ojanguren, whose words seemed to hold so much import. Especially when he says, quoting the Italian philosopher Guido Calogero: “We are all made of other people. I hope some part of me is made of Sridharan”. That was surely a partial answer to my question. In a moment of much longed for epiphany, the full answer became recently available, in the form of Krishna’s words in the following verses of the Bhagavadgītā.7

He who is free from malice towards all beings, friendly and compassionate, and free from the feelings of `I’ and `mine’, balanced in joy and sorrow, forgiving by nature, ever contented and mentally united with Me, that devotee of Mine is dear to Me. (12.13–12.14)

Acknowledgements: It is a pleasure to thank C.S. Aravinda for the opportunity to travel to CMI to cover the event. He also places on record his gratitude to Parimala Raman and Sujatha Ramdorai, for the warm hospitality, and the friendly ambience that made writing this article a pleasant task. He would like to thank all the participants of the 80th Birthday Conference, who willingly spoke to the author, shared their experiences with him, wrote long emails, and even spoke for many hours on the telephone. But for their support and their contributions, this article would not have seen the light of the day. It is a pleasure to record the timely help received from both Sarjick Bakshi and Shraddha Srivastava, graduate students at CMI, in the crucial process of editing, while preparing the final version. Finally, he would like to say that getting to know Sridharan personally has indeed been a privilege, and an unprecedented honour. \blacksquare

Footnotes

- This article is a slightly updated version of the article originally published in the Mathematics Newsletter of the Ramanujan Mathematical Society with the title Sridharan@80 – Polyglot, Polymath, Pure Math by Sudhir Rao, Vol. 26 (2015) pp. 44 – 59, and is republished here, with edits, with permission. ↩

- R. Sridharan, Plum in the middle of Bombay, Independent, Off-beat, Sunday, 2 June (1991), p. 2. An image of this newspaper cutting is entirely reproduced on the back cover of this issue. ↩

- Editor’s note: C.S. Seshadri passed away on 17 July 2020. ↩

- Editor’s note: Nivedita Bhaskhar is presently at the University of Southern California Dornsife, USA. ↩

- Editor’s note: A character from the Mahabharata, known for his valour and most specially for his generosity. ↩

- Editor’s note: K. Chandrasekharan passed away on 13 April 2017. ↩

- The Bhagavadgītā, or, The Song Divine (With Sanskrit text and EnglishTranslation) Gita Press, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, 273005 (INDIA). ↩